Judge William Augustus Bootle and the Desegregation of the University of Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activity As Arrive IDEAS for SIMON SEZ NO out Freeze Dance Clap Position (With Sound, Like Huh) Get to Clap Position, Then Once, Twice, Etc

Activity as Arrive IDEAS FOR SIMON SEZ NO OUT Freeze Dance Clap Position (with sound, like huh) Get to clap position, then once, twice, etc. Welcome in new people Hands normal Words and pix mismatch No flinch Introduce to partners Debrief (JED): - What we just did is “making downtime funtime” - When walked in, could have sat around waiting, looked at phones, or maybe just felt awkward if you didn’t know anyone in room - Instead….fun activity to make downtime funtime - What we are here to discuss - Also, need to model behavior for staff like we did here. Actions speak louder then 1 words….need to walk the talk! - Bonus Debrief! (ROZ) - Why great camp game? - For those that focus on building life skills or 21 st century skills, does it in a fun way…. - Listening Skills - Cooperation/ collaboration (instead of competition) - OK to laugh at yourself - Practice makes you better at everything! - Everyone can have a seat…. 1 ROZ 3:30 – 5 MRPA Thanks for joining us. Announcements from Conference…. Love this session because lots of play. ALSO….a fun benefit of technology…you are going to help determine the content in a few minutes. Going to talk about how you make every minute of the camp day a unique & special part of the experience. We will explore the different times in the camp day when staff can easily transition down-time into fun-time using creative games, activities, songs, dances and more. Can email presentation. Don’t waste paper…give cards at end to email or sign 3 sheet. -

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum

Language Arts Grades K-2: Reading Foundations Skills Block Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum K-2 Reading Foundations Skills Block: Resource Manual EL Education Language Arts Curriculum is published by: EL Education 247 W. 35th Street, 8th Floor New York, NY 10001 www.ELeducation.org ISBN 978-1683622710 FIRST EDITION © 2016 EL Education Inc. Except where otherwise noted, EL Education’s Language Arts Curriculum is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/. Licensed third party content noted as such in this curriculum is the property of the respective copyright owner and not subject to the CC BY 4.0 License. Responsibility for securing any necessary permissions as to such third party content rests with parties desiring to use such content. For example, certain third party content may not be reproduced or distributed (outside the scope of fair use) without additional permissions from the content owner and it is the responsibility of the person seeking to reproduce or distribute this curriculum to either secure those permissions or remove the applicable content before reproduction or distribution. Common Core State Standards © Copyright 2010. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. All rights reserved. Common Core State Standards are subject to the public license located at http://www.corestandards.org/public-license/. Cover art from “First Come the Eggs,” a project by third grade students at Genesee Community Charter School. Used courtesy of Genesee Community Charter School, Rochester, NY. -

Scouting Games. 61 Horse and Rider 54 1

The MacScouter's Big Book of Games Volume 2: Games for Older Scouts Compiled by Gary Hendra and Gary Yerkes www.macscouter.com/Games Table of Contents Title Page Title Page Introduction 1 Radio Isotope 11 Introduction to Camp Games for Older Rat Trap Race 12 Scouts 1 Reactor Transporter 12 Tripod Lashing 12 Camp Games for Older Scouts 2 Map Symbol Relay 12 Flying Saucer Kim's 2 Height Measuring 12 Pack Relay 2 Nature Kim's Game 12 Sloppy Camp 2 Bombing The Camp 13 Tent Pitching 2 Invisible Kim's 13 Tent Strik'n Contest 2 Kim's Game 13 Remote Clove Hitch 3 Candle Relay 13 Compass Course 3 Lifeline Relay 13 Compass Facing 3 Spoon Race 14 Map Orienteering 3 Wet T-Shirt Relay 14 Flapjack Flipping 3 Capture The Flag 14 Bow Saw Relay 3 Crossing The Gap 14 Match Lighting 4 Scavenger Hunt Games 15 String Burning Race 4 Scouting Scavenger Hunt 15 Water Boiling Race 4 Demonstrations 15 Bandage Relay 4 Space Age Technology 16 Firemans Drag Relay 4 Machines 16 Stretcher Race 4 Camera 16 Two-Man Carry Race 5 One is One 16 British Bulldog 5 Sensational 16 Catch Ten 5 One Square 16 Caterpillar Race 5 Tape Recorder 17 Crows And Cranes 5 Elephant Roll 6 Water Games 18 Granny's Footsteps 6 A Little Inconvenience 18 Guard The Fort 6 Slash hike 18 Hit The Can 6 Monster Relay 18 Island Hopping 6 Save the Insulin 19 Jack's Alive 7 Marathon Obstacle Race 19 Jump The Shot 7 Punctured Drum 19 Lassoing The Steer 7 Floating Fire Bombardment 19 Luck Relay 7 Mystery Meal 19 Pocket Rope 7 Operation Neptune 19 Ring On A String 8 Pyjama Relay 20 Shoot The Gap 8 Candle -

CONSTITUTIONAL COURT of SOUTH AFRICA Case CCT 311/17 in the Matter Between: GELYKE KANSE First Applicant DANIËL JOHANNES ROSSOU

CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF SOUTH AFRICA Case CCT 311/17 In the matter between: GELYKE KANSE First Applicant DANIËL JOHANNES ROSSOUW Second Applicant PRESIDENT OF THE CONVOCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Third Applicant BERNARDUS LAMBERTUS PIETERS Fourth Applicant MORTIMER BESTER Fifth Applicant JAKOBUS PETRUS ROUX Sixth Applicant FRANCOIS HENNING Seventh Applicant ASHWIN MALOY Eighth Applicant RODERICK EMILE LEONARD Ninth Applicant and CHAIRPERSON OF THE SENATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH First Respondent CHAIRPERSON OF THE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Second Respondent UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH Third Respondent Neutral citation: Gelyke Kanse and Others v Chairperson of the Senate of the University of Stellenbosch and Others [2019] ZACC 38 Coram: Mogoeng CJ, Cameron J, Froneman J, Jafta J, Khampepe J, Madlanga J, Mathopo AJ, Mhlantla J, Theron J, Victor AJ Judgments: Cameron J (unanimous): [1] to [51] Mogoeng CJ (concurring): [52] to [63] Froneman J (concurring): [64] to [98] Heard on: 8 August 2019 Decided on: 10 October 2019 Summary: Section 29(2) of the Constitution — “reasonably practicable” — constitutionality of the language policy of the University of Stellenbosch — Afrikaans as a medium of instruction – access to higher education Section 6 of the Constitution — protection and promotion of indigenous minority languages — diminished use and status ORDER On direct appeal from the High Court of South Africa, Western Cape Division, Cape Town: 1. Leave to appeal is granted. 2. The appeal is dismissed, with no order as to costs in this Court. 3. The costs orders in the High Court are set aside. 4. In their place is substituted: “There is no order as to costs.” 2 JUDGMENT CAMERON J (Mogoeng CJ, Froneman J, Jafta J, Khampepe J, Madlanga J, Mathopo AJ, Mhlantla J, Theron J and Victor AJ concurring): Introduction [1] At issue is the 2016 Language Policy (2016 Language Policy) of Stellenbosch University, the third respondent. -

Web Site Brochure.Indd

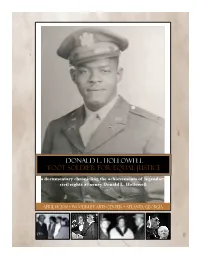

Donald L. Hollowell Foot Soldier for Equal Justice a documentary chronicling the achievements of legendary civil rights attorney Donald L. Hollowell April 15, 2010 * Woodruff Arts Center * Atlanta, Georgia [ Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Esq. Maurice C. Daniels, Dean and Professor Endowment Committee Chairman University of Georgia School of Social Work I finished law school the first I have been a member of the Friday in June 1960. The Monday faculty of the University of morning after I graduated, I went Georgia for more than 25 to work for Donald Hollowell for years. My tenure here was made $35 a week. I was his law clerk possible because of the courage, and researcher, and I carried his commitment, and brilliance of briefcase and I was his right-hand Donald Hollowell. Therefore, I man. He taught me how to be am personally and professionally a lawyer, a leader, how to fight committed to continuing Mr. injustice. Whatever I have become Hollowell’s legacy as a champion in the years, I owe it to him in for the cause of social justice. large measure. — Maurice C. Daniels — Vernon E. Jordan, Jr. Dear Colleagues and Friends, To commemorate and continue the legacy of Donald L. Hollowell, one of our nation’s greatest advocates for social justice, the University of Georgia approved the establishment of the Donald L. Hollowell Professorship of Social Justice and Civil Rights Studies in the School of Social Work. Donald L. Hollowell was the leading civil rights lawyer in Georgia during the 1950s and 1960s. He was the chief architect of the legal work that won the landmark Holmes v. -

Seventy-Sixth Founders' Day at Morris Brown College

VOLUME 31 MORRIS BROWN COLLEGE, ATLANTA, GA., MARCH-APRIL, 1961 Number 4 Seventy-Sixth Founders’ Day At Morris Brown College (Edited By DONALD J. WILSON) The prominent Bishop E. C. Hatcher of Ohio spoke in eloquent Farm, Americus, Georgia; Morris fashion at Morris Brown College as he told the enthusiastic Founders’ Brown College — the Reverend Day audience that Morris Brown was founded to meet the great need Frederick C. James, Sumter, South for undergirding our American education with religious training. This Carolina, Director of the Commit was the 76th observance of the school’s Founders’ Day. Bishop Wilkes tee of Social Action, The African presented the speaker to the audience and the President, Frank Cun Methodist Episcopal Church; and Spelman College — the Reverend ningham presided over the program. Others on the program were Mary William Bell Glenesk, Spencer Me Ann Smith, senior student who brought an inspiring greeting from the morial Presbyterian Church, student body; A. L. Jessie, who gave a progress report on the Alumni Brooklyn, New York. Fund; Dr. H. I. Bearden, Dr. A. L. Harris of Augusta, and Dr. James A committee, whose chairman Debro of the Albany district Also the Bishop S. L. Green, senior bishop was Dr. Frank Cunningham, Presi and several other church notables were presented to the audience. dent of Morris Brown College, was The speaker, Bishop Hatcher, in charge of the affairs of the Re tied in the history of Morris Brown ligious Emphasis Week. The com A Salute For Courage mittee was composed of people with the Negro’s struggle for free from all the schools of the Center. -

Less Than Exciting Behaviors Associated with Unneutered

1 c Less Than Exciting ASPCA Behaviors Associated With Unneutered Male Dogs! Periodic binges of household destruction, digging and scratching. Indoor restlessness/irritability. N ATIONAL Pacing, whining, unable to settle down or focus. Door dashing, fence jumping and assorted escape behaviors; wandering/roaming. Baying, howling, overbarking. Barking/lunging at passersby, fence fighting. Lunging/barking at and fighting with other male dogs. S HELTER Noncompliant, pushy and bossy attitude towards caretakers and strangers. Lack of cooperation. Resistant; an unwillingness to obey commands; refusal to come when called. Pulling/dragging of handler outdoors; excessive sniffing; licking female urine. O UTREACH Sexual frustration; excessive grooming of genital area. Sexual excitement when petted. Offensive growling, snapping, biting, mounting people and objects. Masturbation. A heightened sense of territoriality, marking with urine indoors. Excessive marking on outdoor scent posts. The behaviors described above can be attributed to unneutered male sexuality. The male horomone D testosterone acts as an accelerant making the dog more reactive. As a male puppy matures and enters o adolescence his primary social focus shifts from people to dogs; the human/canine bond becomes g secondary. The limited attention span will make any type of training difficult at best. C a If you are thinking about breeding your dog so he can experience sexual fulfillment ... don’t do it! This r will only let the dog ‘know what he’s missing’ and will elevate his level of frustration. If you have any of e the problems listed above, they will probably get worse; if you do not, their onset may be just around the corner. -

Un Scénario De Julien Rappeneau & Jérome Salle

Un scénario de Julien Rappeneau & Jérome Salle – Publication à but éducatif uniquement – Tous droits réservés - Merci de respecter le droit d’auteur et de mentionner vos sources si vous citez tout ou partie d’un scénario. ZULU Screenplay by Julien Rappeneau and Jérôme Salle Based on the novel by Caryl Férey A film by Jérôme Salle September 21 2012 "Forgiveness liberates the soul. It removes fear That is why it is such a powerful weapon." Nelson Mandela 2. 1 INT. KWAZULU-NATAL TOWNSHIP / ALI’S HOUSE - NIGHT 1 CU on a ten-year-old black child, Ali Sokhela. His face is pressed up to the window. ALI (frightened) Baba... Daddy... Outside, some twenty men in a state of frenzy throw a thirty- year-old black man to the ground. They hit him, insult him, screaming “This is what we do with scum like you!” “All you ANC shits will die!” “We’re gonna fry him like a pig!” KWAZULU-NATAL - SOUTH AFRICA - 1978 A tire is put around the man’s neck. The men throw a lit lighter at him. The tire bursts into flames. Screams of pain blend in with the torturers’ screams of joy. Still pressed up to the window, Ali’s face is lit by the flames. Suddenly a hooded man appears right in front of him, on the other side of the window. Terrified, Ali jumps back. He rushes for the door. Just as he reaches it, two hands try to grab him. He barely escapes. 2 EXT. KWAZULU-NATAL TOWNSHIP - NIGHT 2 In only his underpants, Ali runs as fast as he can. -

The Atlanta Historical Journal

The Atlanta Historical Journal Summer 1981 Volume XXV Number 2 The Atlanta Historical Society OFFICERS Stephens Mitchell E. William Bohn Chairman Emeritus Second Vice-President Beverly M. DuBose, Jr. Tom Watson Brown Chairman Secretary Dr. John B. Hardman Dr. Harvey H. Jackson Vice Chairman Assistant Secretary Jack J. Spalding Julian J. Barfield President Treasurer Henry L. Howell Edward C. Harris First Vice-President Assistant Treasurer TRUSTEES Cecil A. Alexander H. English Robinson Mrs. Ivan Allen, Jr. Mrs. William H. Schroder Dr. Crawford Barnett, Jr. Mrs. Robert Shaw Mrs. Roff Sims Dr. F. Phinizy Calhoun, Jr. John M. Slaton, Jr. Thomas Hal Clarke Mrs. John E. Smith II George S. Craft John A. Wallace F. Tradewell Davis Mrs. Thomas R. Williams Franklin M. Garrett John R. Kerwood, Ex Officio Mrs. William W. Griffin Honorary Richard A. Guthman, Jr. The Hon. Anne Cox Chambers Dr. Willis Hubert Mrs. Richard W. Courts, Jr. George Missbach Philip T. Shutze Robert W. Woodruff Mrs. John Mobley Virlyn B. Moore, Jr. William A. Parker, Jr. William L. Pressly EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD Dr. Gary M. Fink Dr. Robert C. McMath, Jr. Georgia State University Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Jane Herndon Dr. Bradley R. Rice DeKalb Community College Clayton Junior College Dr. Harvey H. Jackson Dr. S. Fred Roach Clayton Junior College Kennesaw College Dr. George R. Lamplugh Dr. Philip Secrist The Westminster Schools Southern Technical Institute The Atlanta Historical Journal Franklin M. Garrett Editor Emeritus Ann E. Woodall Editor Harvey H. Jackson Book Review Editor Volume XXV, Number 2 Summer 1981 Copyright 1981 by Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. -

History of *Columbus

www.gagenweb.org (C) 2005 Electronic Edition nated Abraham Lincoln. Following all these disturbances in the National Democratic party's membership in this state and other sections, three nominees were put up for President, each having ardent supporters among all the slave-holding states. Douglas and Johnson, Bell and Elliot, and Breckenridge and Lane, all had their votes and were upheld in Georgia respectively by Stephens, Hill, and Toombs. These Georgians stumped the state for their favorites, all coming to Columbus. Douglas accompanied by Stephens addressid a large gathering from the porch of the Oglethorpe Hotel. Hill and Toombs at other times spoke from the same place. The result of the campaign in Georgia was the selection of a Brecken- ridge and Lane electoral ticket at the Democratic State convention on Au- gust 8, 1860. Peyton H. Colquitt and his brother, Alfred H. Colquitt, were both delegates, though from different counties. At the subsequent Douglas and Johnson convention many supporters went over to the Breckenridge and Lane ticket, among them A. H. Chappell, one of the most ardent leaders. The result of the national election came eventually, however, and Lincoln and Hamlin were announced victorious. The effect on the South was instantaneous and maddening. The Georgia legislature, the same as of 1 8 59, assembled and made Gen. C. J. Williams, of Columbus, Speaker of the House, in place of I. T. Irwin who had died. The main action of the legislature was the calling of a convention of the people of the state to be held January 16th, 1861, at Milledgeville to take up the matter of union or secession. -

Educational Programs for Professional Identity Formation: the Role of Social Science Research

BEBEAU PROOF (DO NOT DELETE) 6/12/2017 2:37 PM Educational Programs for Professional Identity Formation: The Role of Social Science Research by Muriel J. Bebeau* Stephen J. Thoma** and Clark D. Cunningham*** I. INTRODUCTION This Article on the use of social science research to design, implement, and assess educational programs for the development of professional identity has its origins in the opening presentation made at the 17th An- nual Georgia Symposium on Professionalism and Legal Ethics, held on October 7, 2016 at Mercer Law School on the topic “Educational Inter- ventions to Cultivate Professional Identity in Law Students.”1 The Mer- cer Symposium invited speakers from a variety of disciplines to address *Professor, Department of Primary Dental Care, School of Dentistry, and Adjunct Pro- fessor, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Minnesota; Director Emerita, Center for the Study of Ethical Development. **University Professor at the University of Alabama and Director of the Center for the Study of Ethical Development. ***Professor of Law and holds the W. Lee Burge Chair in Law & Ethics at the Georgia State University College of Law in Atlanta, www.ClarkCunningham.org, directs the Na- tional Institute for Teaching Ethics & Professionalism, www.niftep.org, and is co-editor of the International Forum on Teaching Legal Ethics & Professionalism, www.teachinglegal ethics.org. 1. The opening presentation was to be given by one of us—Bebeau—but last minute family issues prevented her participation in the conference so another of us—Cunning- ham—took her place to present an overview of the Four Component Model of Morality (FCM) together with some of the research findings that have implications for the central 591 BEBEAU PROOF (DO NOT DELETE) 6/12/2017 2:37 PM 592 MERCER LAW REVIEW [Vol.