Was Hendrick Ter Brugghen a Melancholic?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst Cornelis De Bie, Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst 244

Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst Cornelis de Bie bron Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst. Jan Meyssens, Juliaen van Montfort, Antwerpen 1662 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/bie_001guld01_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl 1 Het gulden cabinet vande edele vry schilder-const Ontsloten door den lanck ghevvenschten Vrede tusschen de twee mach- tighe Croonen van SPAIGNIEN EN VRANCRYCK, Waer-inne begrepen is den ontsterffe- lijcken loff vande vermaerste Constminnende Geesten ENDE SCHILDERS Van dese Eeuvv, hier inne meest naer het leven af-gebeldt, verciert met veel ver- makelijcke Rijmen ende Spreucken. DOOR Cornelis de Bie Notaris binnen Lyer. Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst 3 Den geboeyden Mars spreckt op d'uytleggingh van de titel plaet. WEl wijckt dan mijne Macht, en Raserny ter sijden? Moet mijne wreetheyt nu dees boose schant-vleck lijden? Dat ick hier ligh gheboyt en plat ter aert ghedruckt, Ontrooft van Sweert en Schilt, t'gen' my is af-geruckt? Alleen door liefdens kracht, die Vranckrijck heeft ontsteken, Die door het Echts verbont compt al mijn lusten breken, Die selffs de wreetheyt ben, wordt hier van liefd' gheplaegt, Den dullen Orloghs Godt wordt van den Peys verjaeght. Ach! d' Edel Fransche Trouw: (aen Spaenien verbonden:) Die heeft m' allendigh Helt in ballinckschap ghesonden. K' en heb niet eenen vriendt, men danckt my spoedigh aff Een jeder my verstoot, ick sien ick moet in't graff. Nochtans sal menich mensch mijn ongeluck beclaghen Die was ghewoon door my heel Belgica te plaeghen, Die was ghewoon met my te liggen op het landt Dat ick had uyt gheput door mijnen Orloghs brandt, De deught had ick verjaeght, en liefdens kracht ghenomen Midts dat mijn fury was in Neder-landt ghecomen Tot voordeel vanden Frans, die my nu brenght in druck En wederleyt mijn jonst, fortuyn en groot gheluck. -

Il Tempo Di Caravaggio. Capolavori Della Collezione

COMUNICATO STAMPA Prorogata al 10 gennaio 2021 la mostra “Il tempo di Caravaggio. Capolavori della collezione di Roberto Longhi” ai Musei Capitolini Altri 4 mesi per ammirare il famoso Ragazzo morso da un ramarro di Caravaggio e oltre quaranta dipinti di artisti della sua cerchia, provenienti dalla raccolta del grande storico dell’arte e collezionista Roberto Longhi Roma, 08 settembre 2020 – È stata prorogata fino al 10 gennaio 2021 la mostra “Il tempo di Caravaggio. Capolavori della collezione di Roberto Longhi”, allestita nelle sale espositive di Palazzo Caffarelli ai Musei Capitolini e aperta al pubblico il 16 giugno. L’esposizione, accolta con grande favore dal pubblico e dalla critica, è promossa da Roma Capitale, Assessorato alla Crescita culturale - Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali e dalla Fondazione di Studi di Storia dell’Arte Roberto Longhi. Curata da Maria Cristina Bandera, Direttore scientifico della Fondazione Longhi, la mostra è organizzata da Civita Mostre e Musei e Zètema Progetto Cultura. Il catalogo è di Marsilio Editori. L’ingresso è gratuito per i possessori della MIC card. L’esposizione è aperta al pubblico nel rispetto delle linee guida formulate dal Comitato Tecnico Scientifico per contenere la diffusione del Covid-19 consentendo, al contempo, lo svolgimento di una normale visita museale. L’esposizione è dedicata alla raccolta dei dipinti caravaggeschi del grande storico dell’arte e collezionista Roberto Longhi (Alba 1890 – Firenze 1970), una delle personalità più affascinanti della storia dell’arte del XX secolo, di cui ricorre quest’anno il cinquantenario della scomparsa. Nella sua dimora fiorentina, villa Il Tasso, oggi sede della Fondazione che gli è intitolata, raccolse un numero notevole di opere dei maestri di tutte le epoche che furono per lui occasione di ricerca. -

ART 486 / 586 Baroque Art Fall 2018

ART 486 / 586 Baroque Art fall 2018 Instructor: Jill Carrington [email protected] tel. 468-4351; Office 117 Office hours: MWF 11:00 - 11:30, MW 4:00 – 5:00; TR after class until noon, TR 4:00 – 5:00 other times by appt. Class meets TR 9:30 – 10:45 in the Art History Room 106 in the Art Annex Building. Course description: European art from 1600 to 1750. Prerequisites: 6 hours in art including ART 281, 282 or the equivalent in history. Program Learning Outcomes (for art history majors, of which there are none in the class) 1. Foundation Skills 2. Interpretative Skills 3. Research Skills Undergraduate students will conduct art historical research involving logical and insightful analysis of secondary literature. Category: Embedded course assignment (research paper) Text: Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth Century Art and Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2e, 2008 or 1e, 2005. One copy of the 1e is on four-hour reserve in Steen Library. Used copies of the both 1e and 2e are available online; for example, on Aug. 22 there were 3 used copies of the 1st ed in acceptable condition for less than $7.19 or 7.23 and one good for $11.98 on bookfinder.com. I don’t require you to buy the book; however, you may want your own copy or share one at exam times. Work schedule: A. 2 non-comprehensive quizzes identifying works and terms, collectively worth 20% if higher than other work, 10% if lower. The extra 5% will count toward other work with the highest grade. -

Creativity Over Time and Space

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Serafinelli, Michel; Tabellini, Guido Working Paper Creativity over Time and Space IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12644 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Serafinelli, Michel; Tabellini, Guido (2019) : Creativity over Time and Space, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 12644, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/207469 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12644 Creativity over Time and Space Michel Serafinelli Guido Tabellini SEPTEMBER 2019 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 12644 Creativity over Time and Space Michel Serafinelli University of Essex, IZA and CReAM Guido Tabellini IGIER, Università Bocconi, CEPR, CESifo and CIFAR SEPTEMBER 2019 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. -

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 3, Fall 2018

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 3, Fall 2018 An Affiliated Society of: College Art Association Society of Architectural Historians International Congress on Medieval Studies Renaissance Society of America Sixteenth Century Society & Conference American Association of Italian Studies President’s Message from Sean Roberts Rosen and I, quite a few of our officers and committee members were able to attend and our gathering in Rome September 15, 2018 served too as an opportunity for the Membership, Outreach, and Development committee to meet and talk strategy. Dear Members of the Italian Art Society: We are, as always, deeply grateful to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation for their support this past decade of these With a new semester (and a new academic year) important events. This year’s lecture was the last under our upon us once again, I write to provide a few highlights of current grant agreement and much of my time at the moment IAS activities in the past months. As ever, I am deeply is dedicated to finalizing our application to continue the grateful to all of our members and especially to those lecture series forward into next year and beyond. As I work who continue to serve on committees, our board, and to present the case for the value of these trans-continental executive council. It takes the hard work of a great exchanges, I appeal to any of you who have had the chance number of you to make everything we do possible. As I to attend this year’s lecture or one of our previous lectures to approach the end of my term as President this winter, I write to me about that experience. -

The Rijksmuseum Bulletin

the rijksmuseum bulletin 162 the rijks museum bulletin Acquisitions History and Print Room • jenny reynaerts, huigen leeflang, marijn schapelhouman, jeroen luyckx, mei jet broers and harm stevens • 1 attributed to nicolaes de kemp (c. 1550-1600) Genealogy of the Lords and Counts of Culemborg Utrecht, c. 1590-93 Vellum, gouache, ink, silver paint, gold, pigskin, 422 x 312 x 40 mm Around 1590 Floris I of Pallandt, Count of Culem- the family. The genealogy ends with the Pallandts borg, had a genealogy made. The creation of the – Floris’s parents. Dutch Republic some years before had put an end The genealogy is an unusual example of the to princely rule and the exceptional status of the nobility in the Low Countries’ urge to display nobility. The nobles tried to compensate for this their distinguished lineage. The illustrations are through symbolism. To set themselves apart from excellent quality – strikingly the figures have the middle-class ruling elite they stressed their individual facial features. The maker spent a great long lineage of important forebears. Floris I also deal of time on the details and tried to produce tried to legitimize his unique historic status: the the faces of the legendary ancestors as portraits. genealogy, which went back to ad 800, showed It is clear that he based the last generations on that he had come from an illustrious family. existing examples. The figures’ clothes vary from The manuscript consists of fifty-five vellum sheet to sheet, and the artist has even taken the sheets with illustrations attributed to Nicolaes de trouble to reflect the changing fashion through Kemp. -

The Arts Thrive Here

Illustrated THE ARTS THRIVE HERE Art Talks Vivian Gordon, Art Historian and Lecturer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: REMEMBERING BIBLICAL WOMEN ARTISTS IN THEIR STUDIOS Monday, April 13, at 1PM Wednesday, May 20, at 1PM Feast your eyes on some of the most Depicting artists at work gives insight into the beautiful paintings ever. This illustrated talk will making of their art as well as their changing status examine how and why biblical women such as in society.This visual talk will show examples Esther, Judith, and Bathsheba, among others, from the Renaissance, the Impressionists, and were portrayed by the “Masters.” The artists Post-Impressionists-all adding to our knowledge to be discussed include Mantegna, Cranach, of the nature of their creativity and inspiration. Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt. FINE IMPRESSIONS: CAILLEBOTTE, SISLEY, BAZILLE Monday, June 15, at 1PM This illustrated lecture will focus on the work of three important (but not widely known) Impressionist painters. Join us as Ms. Gordon introduces the art, lives and careers of these important fi gures in French Impressionist art. Ines Powell, Art Historian and Educator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will present the following: ALBRECHT DURER and HANS HOLBEIN the ELDER Thursday, April 23, at 1PM Unequaled in his artistic and technical execution of woodcuts and engravings, 16th century German artist Durer revolutionized the art world, exploring such themes as love, temptation and power. Hans Holbein the Elder was a German painter, a printmaker and a contemporary of Durer. His works are characterized by deep, rich coloring and by balanced compositions. -

GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO DIPINTI ANTICHI Venticinque Anni Di Attività

GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO DIPINTI ANTICHI Venticinque anni di attività La GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO, fondata a Torino nel 1993 La Galleria Giamblanco di Torino festeggia da Deborah Lentini e Salvatore Giamblanco, da oltre venticinque anni offre ai suoi clienti dipinti di grandi maestri italiani e stranieri con questo catalogo i suoi primi venticinque anni dal Cinquecento al primo Novecento, attentamente selezionati per qualità e rilevanza storico-artistica, avvalendosi di attività, proponendo al pubblico un’ampia selezione della consulenza dei migliori studiosi. di dipinti dal XV al XIX secolo. Tra le opere più importanti si segnalano inediti di Nicolas Régnier, Mattia Preti, Joost van de Hamme, Venticinque anni di attività Gioacchino Assereto, Cesare e Francesco Fracanzano, Giacinto Brandi, Antonio Zanchi e di molti altri artisti di rilievo internazionale. Come di consueto è presentata anche una ricca selezione di autori piemontesi del Sette e dell’Ottocento, da Vittorio Amedeo Cignaroli a Enrico Gamba, tra cui i due bozzetti realizzati da Claudio Francesco Beaumont per l’arazzeria di corte sabauda, che vanno a completare la serie oggi conservata al Museo Civico di Palazzo Madama di Torino. Catalogo edito per la Galleria Giamblanco da 2017-2018 In copertina UMBERTO ALLEMANDI e 26,00 Daniel Seiter (Vienna, 1647 - Torino, 1705), «Diana e Orione», 1685 circa. GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO DIPINTI ANTICHI Venticinque anni di attività A CURA DI DEBORAH LENTINI E SALVATORE GIAMBLANCO CON LA COLLABORAZIONE DI Alberto Cottino Serena D’Italia Luca Fiorentino Simone Mattiello Anna Orlando Gianni Papi Francesco Petrucci Guendalina Serafinelli Nicola Spinosa Andrea Tomezzoli Denis Ton Catalogo edito per la Galleria Giamblanco da UMBERTO ALLEMANDI Galleria Giamblanco via Giovanni Giolitti 39, Torino tel. -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart Kok, E.E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kok, E. E. (2013). Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Summary Jacob Backer (1608/9-1651), Govert Flinck (1615-1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), and Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) belong among the most successful portrait and history painters of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

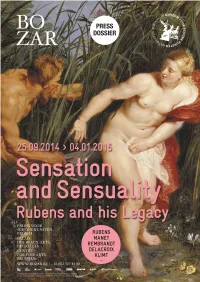

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

ARTS 5306 Crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art History Fall 2020

ARTS 5306 crosslisted with 4306 Baroque Art HIstory fall 2020 Instructor: Jill Carrington [email protected] tel. 468-4351; Office 117 Office hours: MWF 11:00 - 11:30, MW 4:00 – 5:00; TR 11:00 – 12:00, 4:00 – 5:00 other times by appt. Class meets TR 2:00 – 3:15 in the Art History Room 106 in the Art Annex and remotely. Course description: European art from 1600 to 1750. Prerequisites: 6 hours in art including ART 1303 and 1304 (Art History I and II) or the equivalent in history. Text: Not required. The artists and most artworks come from Ann Sutherland Harris, Seventeenth Century Art and Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2e, 2008 or 1e, 2005. One copy of the 1e is on four-hour reserve in Steen Library. Used copies of the both 1e and 2e are available online; for I don’t require you to buy the book; however, you may want your own copy or share one. Objectives: .1a Broaden your interest in Baroque art in Europe by examining artworks by artists we studied in Art History II and artists perhaps new to you. .1b Understand the social, political and religious context of the art. .2 Identify major and typical works by leading artists, title and country of artist’s origin and terms (id quizzes). .3 Short essays on artists & works of art (midterm and end-term essay exams) .4 Evidence, analysis and argument: read an article and discuss the author’s thesis, main points and evidence with a small group of classmates.