Montgomery County Reconnaissance Level Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithfield Review, Volume 20, 2016

In this issue — On 2 January 1869, Olin and Preston Institute officially became Preston and Olin Institute when Judge Robert M. Hudson of the 14th Circuit Court issued a charter Includes Ten Year Index for the school, designating the new name and giving it “collegiate powers.” — page 1 The On June 12, 1919, the VPI Board of Visitors unanimously elected Julian A. Burruss to succeed Joseph D. Eggleston as president of the Blacksburg, Virginia Smithfield Review institution. As Burruss began his tenure, veterans were returning from World War I, and America had begun to move toward a post-war world. Federal programs Studies in the history of the region west of the Blue Ridge for veterans gained wide support. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women Volume 20, 2016 suffrage, gained ratification. — page 27 A Note from the Editors ........................................................................v According to Virginia Tech historian Duncan Lyle Kinnear, “he [Conrad] seemed Olin and Preston Institute and Preston and Olin Institute: The Early to have entered upon his task with great enthusiasm. Possessed as he was with a flair Years of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Part II for writing and a ‘tongue for speaking,’ this ex-confederate secret agent brought Clara B. Cox ..................................................................................1 a new dimension of excitement to the school and to the town of Blacksburg.” — page 47 Change Amidst Tradition: The First Two Years of the Burruss Administration at VPI “The Indian Road as agreed to at Lancaster, June the 30th, 1744. The present Faith Skiles .......................................................................................27 Waggon Road from Cohongoronto above Sherrando River, through the Counties of Frederick and Augusta . -

Popular Sovereignty, Slavery in the Territories, and the South, 1785-1860

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Popular sovereignty, slavery in the territories, and the South, 1785-1860 Robert Christopher Childers Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Childers, Robert Christopher, "Popular sovereignty, slavery in the territories, and the South, 1785-1860" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1135. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1135 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY, SLAVERY IN THE TERRITORIES, AND THE SOUTH, 1785-1860 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Robert Christopher Childers B.S., B.S.E., Emporia State University, 2002 M.A., Emporia State University, 2004 May 2010 For my wife ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing history might seem a solitary task, but in truth it is a collaborative effort. Throughout my experience working on this project, I have engaged with fellow scholars whose help has made my work possible. Numerous archivists aided me in the search for sources. Working in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gave me access to the letters and writings of southern leaders and common people alike. -

Lancaster House Venue Hire

Lancaster House Venue Hire “I have come from my house to your palace” —Queen Victoria Steeped in political history, discover magnificent Lancaster House with fabulous Louis XIV style interiors, stunning art collection, beautiful terrace and garden. Situated adjacent to Buckingham Palace, this historic house provides an impressive setting and first-class facilities for your event, reception, conference or other special occasion. The Grand Hall and Staircase On entering the house through the portico, the Grand Hall opens up to reveal a sweeping staircase and balustrade, in an echo of the Palace of Versailles. Both features are part of architect’s Benjamin Wyatt’s original design. Over the past two centuries numerous high-profile occasions have taken place here, from society banquets to international summits and receptions. With its ornate ceiling, marble walls and beautiful frescoes, the Grand Hall is a wonderful location to hold receptions, with a capacity of 200 available to experience the splendour of Lancaster House. To enquire about booking the Grand Hall and other fine rooms contact the team on +44 (0)20 7008 2711 from 0800–1700 Monday to Friday or email lancasterhouse. [email protected]. The Long Gallery More than 35 metres in length, the Long Gallery dominates the whole of the east side of the house. With 18 windows and a large ornate skylight, the room is filled with natural light. Winston Churchill gave a Coronation Banquet for the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II here in June 1953. Long Gallery maximum capacities Reception Boardroom Theatre-style Seated meal 350 60* 200 150 *plus a further 120 people seated beside and behind table The Music Room With windows opening onto a balcony and recesses flanked by Corinthian columns, the music room is the wonderful venue for meetings, press briefings or formal dinners. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third and last installment of the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans, to be republished in JBS. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement BY RICHARD OSBORN Patriot (1775-1778) Revolutions ultimately conclude with a large scale resolution in the major political, social, and economic issues raised by the upheaval. During the final two years of the American Revolution, William Preston struggled to anticipate and participate in the emerging American regime. For Preston, the American Revolution involved two challenges--Indians and Loyalists. The outcome of his struggles with both groups would help determine the results of the Revolution in Virginia. If Preston could keep the various Indian tribes subdued with minimal help from the rest of Virginia, then more Virginians would be free to join the American armies fighting the English. But if he was unsuccessful, Virginia would have to divert resources and manpower away from the broader colonial effort to its own protection. The other challenge represented an internal one. A large number of Loyalist neighbors continually tested Preston's abilities to forge a unified government on the frontier which could, in turn, challenge the Indians effectivel y and the British, if they brought the war to Virginia. In these struggles, he even had to prove he was a Patriot. Preston clearly placed his allegiance with the revolutionary movement when he joined with other freeholders from Fincastle County on January 20, 1775 to organize their local county committee in response to requests by the Continental Congress that such committees be established. -

St James Conservation Area Audit

ST JAMES’S 17 CONSERVATION AREA AUDIT AREA CONSERVATION Document Title: St James Conservation Area Audit Status: Adopted Supplementary Planning Guidance Document ID No.: 2471 This report is based on a draft prepared by B D P. Following a consultation programme undertaken by the council it was adopted as Supplementary Planning Guidance by the Cabinet Member for City Development on 27 November 2002. Published December 2002 © Westminster City Council Department of Planning & Transportation, Development Planning Services, City Hall, 64 Victoria Street, London SW1E 6QP www.westminster.gov.uk PREFACE Since the designation of the first conservation areas in 1967 the City Council has undertaken a comprehensive programme of conservation area designation, extensions and policy development. There are now 53 conservation areas in Westminster, covering 76% of the City. These conservation areas are the subject of detailed policies in the Unitary Development Plan and in Supplementary Planning Guidance. In addition to the basic activity of designation and the formulation of general policy, the City Council is required to undertake conservation area appraisals and to devise local policies in order to protect the unique character of each area. Although this process was first undertaken with the various designation reports, more recent national guidance (as found in Planning Policy Guidance Note 15 and the English Heritage Conservation Area Practice and Conservation Area Appraisal documents) requires detailed appraisals of each conservation area in the form of formally approved and published documents. This enhanced process involves the review of original designation procedures and boundaries; analysis of historical development; identification of all listed buildings and those unlisted buildings making a positive contribution to an area; and the identification and description of key townscape features, including street patterns, trees, open spaces and building types. -

Lancaster House Agreement

SOUTHERN RHODESIA CONSTITUTIONAL CONFERENCE HELD AT LANCASTER HOUSE, LONDON SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 1979 REPORT 1. Following the Meeting of Commonwealth Heads of Government held in Lusaka from 1 to 7 August, Her Majesty's Government issued invitations to Bishop Muzorewa and the leaders of the Patriotic Front to participate in a Constitutional Conference at Lancaster House. The purpose of the Conference was to discuss and reach agreement on the terms of an Independence Constitution, and that elections should be supervised under British authority to enable Rhodesia to proceed to legal independence and the parties to settle their differences by political means. 2. The Conference opened on 10 September under the chairmanship of Lord Carrington, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs. The Conference concluded on 15 December, after 47 plenary sessions. A list of the official delegates to the Conference is at Annex A. The text of Lord Carrington's opening address is at Annex B, together with statements made by Mr Nkomo on behalf of his and Mr Mugabe's delegation and by Bishop Muzorewa on behalf of his delegation. 3. In the course of its proceedings the Conference reached agreement on the following issues: — Summary of the Independence Constitution (attached as Annex C to this report)* —arrangements for the pre-independence period (Annex D) —a cease-fire agreement signed by the parties (Annex E) 4. In concluding this agreement and signing this report the parties undertake: (a) to accept the authority of the Governor; (b) to abide by the Independence Constitution; (c) to comply with the pre-independence arrangements; (d) to abide by the cease-fire agreement; (e) to campaign peacefully and without intimidation; (f) to renounce the use of force for political ends; (g) to accept the outcome of the elections and instruct any forces under their authority to do the same. -

The Chronicle Thursday

THE CHRONICLE THURSDAY. FEBRUARY 4, 1988 © DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM. NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 83. NO. 93 Ticket Reagan to speak on campus Monday information By DAN BERGER all students who don't get tickets to the President Reagan will visit the Univer speech will come out to see the landing," Undergraduates: ASDU will distribute sity Monday to speak at a conference on he said. Several local high school bands 2,500 free tickets for President substance abuse, the White House an and community groups will also attend Reagan's speech to undergraduates nounced Wednesday. the ceremony at the landing site, Mizell presenting a student ID between 10 Reagan will address the conference said. He added that the men's basketball a.m. and 4 p.m. Thursday at the upper "Substance Abuse in the Workplace: team will likely participate in the fevet of the Bryan Center. Another dis Strategies for the 1990s," which is being program at the lacrosse field prior to the tribution table may be set up at the East sponsored by the University and the office president's landing and to a lesser extent Campus Union during the same hours, of North Carolina Gov. Jim Martin. The after he arrives. but a final decision will not be made un president's trip from Washington D.C. Before taking the dais, Reagan will hold til Thursday morning. Of the 2,500 tick will be made exclusively to attend the a closed meeting in Cameron with several ets, 750 will be allocated to East Cam event. community leaders affiliated with the pus. -

1901 Census of Thanet Places Enumerated, with Index

1901 Census of Thanet Places Enumerated, with Index Scope The complete Thanet Registration District, enumerated on the following pieces : • RG13/819 Acol, Birchington, Minster, Monkton, Sarre, St Nicolas, Stonar • RG13/820 Margate, Westgate • RG13/821 Margate • RG13/822 Margate • RG13/823 Margate • RG13/824 Margate • RG13/825 Ramsgate • RG13/826 Ramsgate • RG13/827 St Lawrence • RG13/828 Broadstairs, St Lawrence, St Peter • RG13/829 St Lawrence, St Peter This is a finding aid, and punctuation, capitalisation and spelling may have been changed. Arrangement The first part is in sections, each corresponding to an Enumeration District. The entries in each section give the place-related information for the district, arranged in columns : • piece & folio : used with the class number (RG13) to identify the original source • Dwellings and Buildings : names or descriptions of individual dwellings and buildings ~ also includes groups such as ‘cottages’ & ‘almshouses’ • Streets, Hamlets, etc : names used for groups of dwellings & buildings ~ as well as streets and hamlets, also includes places such as ‘courts’, ‘gardens’, ‘terraces’, ‘yards’, etc • parish : the ecclesiastical parish or district, abbreviated as noted below • location : the town or civil parish. In a some cases the information under this heading may be the only place-related data given in the original, and nothing is entered under ‘Dwellings’ or ‘Streets’ The second part (starting on page 75) is a combined Index of Dwellings and Streets, each entry giving piece and folio number(s). -

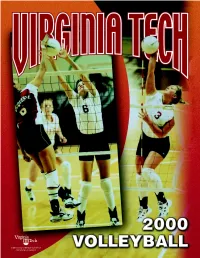

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY 20002000 VirginiaVirginia TechTech VolleyballVolleyball Table of Contents 2000 Schedule Facilities/Media Services ............................................................ 2 Date Opponent Time 2000 Rosters ............................................................................... 3 Sept. 1-2 HOKIE CLASSIC 2000 Outlook ............................................................................ 4-5 1 MARSHALL 12:45 p.m. Travel Plans ................................................................................ 5 APPALACHIAN STATE 7:30 p.m. 2 NORTH CAROLINA STATE 3 p.m. Head Coach Greg Smith/Support Staff ....................................... 6 SOUTHWEST TEXAS 7:30 p.m. Assistant Coaches ...................................................................... 7 8-9 Wildcat Classic @ Manhattan, Kan. Player Profiles ........................................................................ 8-17 8 vs. Air Force 5 p.m. CT Opponents ................................................................................ 18 9 vs. Bradley 10 a.m. CT 1999 Year in Review ................................................................. 19 9 at Kansas State 7:30 p.m. CT 1999 Statistics/Results .............................................................. 20 13 at Radford 7 p.m. Single Season/Career Records ........................................... 21-22 15 GEORGE MASON 7 p.m. Team/Individual Records .......................................................... 23 22-23 JMU Tournament @ Harrisonburg, -

COVERING VIRGINIA TECH} SOCIETY for NEWS DESIGN How to Reach Us Submissions, Suggestions and Comments Are Welcome

ALSO INSIDE: O H I O U N I V E R S I T Y ’ S visua l j ourn a l is m p ro g R a m PLUS: T H E 1 9 th a nnua l c O l l E g E ne w S d esi g N c ontest Who is he talking about? What was he like? What will happen to Norris? Why Norris Hall? Will students ever be the same? What will the rest of the semester be like? How long will the media stay? When did he tape that video? Why did he do it? Why was UpdateM AY/J U N E 2 0 0 7 Emily Hilscher rst? Why did he photograph himself that way? Why did he send the package to NBC? Will a lot of students come back for the rest of the semester? How will this aect the prospective freshman class? What will happen to his dorm room? Why would he kill people he doesn’t know? Will security change? Can campus be safe again? How will they handle graduation? Where do we go from here? What will happen with classes? Who is he talking about? What was he like? What will happen to Norris? Why Norris Hall? Will students ever be the same? What will the rest of the semester be like? How long will the Why? How will they handle media stay? When did he tape that video? graduation? Where do we go from Why did he do it? Why was Emily Hilscher here? What will happen with classes? rst? Why did he photograph himself that Who is he talking about? What was he way? Why did he send the package to NBC? like? What will happen to Norris? Why Will a lot of students come back for the rest Norris Hall? Will students ever be the same? of the semester? How will this aect the What will the rest of the semester be like? prospective freshman -

The Stroubles Creek Watershed: History of Development and Chronicles of Research

The Stroubles Creek Watershed: History of Development and Chronicles of Research By Tammy Parece Stephanie DiBetitto Tiffany Sprague Tamim Younos VWRRC Special Report No. SR48-2010 VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY BLACKSBURG, VIRGINIA May 2010 Acknowledgments This document compiles past and contemporary research reports on the Stroubles Creek watershed. Acknowledgements are due to many Virginia Tech faculty/students and larger community members who have studied the Stroubles Creek for nearly one hundred years. The development of this comprehensive report was made possible by a National Science Foundation Research Experiences for Undergraduates (NSF REU) program funding (Grant No. 0649070) which provided summer internship support to two co-authors of this report, i.e., Ms. Stephanie DiBetitto (University of Vermont) and Ms. Tiffany Sprague (James Madison University). Others who made significant contributions to this report include Dr. Gene Yagow (VT Biological Systems Engineering Department), Dr. James Campbell (VT Geography Department), Ms. Llyn Sharp (VT Geosciences Outreach), Dr. Vinod Lohani (VT Engineering Education), Ms. Tara McCloskey and Ms. Erica Adams (Geography Department Graduate Students), and Ms. Erika Karsh a volunteer summer research assistant from Oberlin University. ******************************************** Disclaimer The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied,