Into Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob Zuma: the Man of the Moment Or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu

Research & Assessment Branch African Series Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu Key Findings • Zuma is a pragmatist, forging alliances based on necessity rather than ideology. His enlarged but inclusive cabinet, rewards key allies with significant positions, giving minor roles to the leftist SACP and COSATU. • Long-term ANC allies now hold key Justice, Police and State Security ministerial positions, reducing the likelihood of legal charges against him resurfacing. • The blurring of party and state to the detriment of public institutions, which began under Mbeki, looks set to continue under Zuma. • Zuma realises that South Africa relies too heavily on foreign investment, but no real change in economic policy could well alienate much of his populist support base and be decisive in the longer term. 09/08 Jacob Zuma: The Man of the Moment or the Man for the Moment? Alex Michael & James Montagu INTRODUCTION Jacob Zuma, the new President of the Republic of South Africa and the African National Congress (ANC), is a man who divides opinion. He has been described by different groups as the next Mandela and the next Mugabe. He is a former goatherd from what is now called KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) with no formal education and a long career in the ANC, which included a 10 year spell at Robben Island and 14 years of exile in Mozambique, Swaziland and Zambia. Like most ANC leaders, his record is not a clean one and his role in identifying and eliminating government spies within the ranks of the ANC is well documented. -

Final Reviewed Integrated Development Plan 2020/21

FINAL REVIEWED INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020/21 VISION “A Spatially Integrated & Sustainable Local Economy by 2030” MISSION To ensure the provision of sustainable basic services and infrastructure to improve the quality of life of our people and to grow the local economy for the benefit of all citizen VALUES Transparency, Accountability, Responsive, Professional Creative integrity TABLE OF CONTENT CONTENT PAGE TABLE OF CONTENT i LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………………………..vii LIST OF TABLES viii ABBREVIATIONS x FOREWORDS xii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 01 1.1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ………………………………………………………………..01 1.2. BACKGROUND 02 1.3. LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 07 1.3.1. Constitution of South Africa Act (no. 108 of 1996) 07 1.3.2. Municipal Systems Act (no. 32 of 2000) 07 1.3.3. Municipal Finance Management Act (no. 56 of 2003) 08 1.4. PLANNING FRAMEWORK 10 1.5. POWERS AND FUCTIONS 11 1.6. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS TO DRIVE THE IDP 12 1.7. IDPPLANNING PROCESS PLAN, ROLE AND PURPOSE 14 1.7.1. IDP Framework and Process Plan 14 1.7.1.1. Preparation phase 15 1.7.1.2. Analysis Phase 24 1.7.1.3. Strategy Phase 27 1.7.1.4. Project Phase 28 1.7.1.5. Integration Phase 28 1.7.1.6. Approval Phase 28 SECTION A: ANALYSIS PHASE………………………………………………………………..30 CHAPTER 2: DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE……………………………………………….……..30 2.1. POPULATION SIZE AND COMPOSITION 30 2.2. POPULATION AGE AND GENDER DISTRUBUTION 32 2.3. SOCIAL GRANT POPULATION BY NODAL POINTS 33 2.4. EDUCATION PROFILE 33 2.5. PERFORMANCE PRE DISTRICT (Grade 12) 35 2.6. HOUSEHOLD TRENDS 36 2.7. -

Who Is Governing the ''New'' South Africa?

Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa? Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard To cite this version: Marianne Séverin, Pierre Aycard. Who is Governing the ”New” South Africa?: Elites, Networks and Governing Styles (1985-2003). IFAS Working Paper Series / Les Cahiers de l’ IFAS, 2006, 8, p. 13-37. hal-00799193 HAL Id: hal-00799193 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00799193 Submitted on 11 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ten Years of Democratic South Africa transition Accomplished? by Aurelia WA KABWE-SEGATTI, Nicolas PEJOUT and Philippe GUILLAUME Les Nouveaux Cahiers de l’IFAS / IFAS Working Paper Series is a series of occasional working papers, dedicated to disseminating research in the social and human sciences on Southern Africa. Under the supervision of appointed editors, each issue covers a specifi c theme; papers originate from researchers, experts or post-graduate students from France, Europe or Southern Africa with an interest in the region. The views and opinions expressed here remain the sole responsibility of the authors. Any query regarding this publication should be directed to the chief editor. Chief editor: Aurelia WA KABWE – SEGATTI, IFAS-Research director. -

An Exploration of the 2016 Violent Protests in Vuwani, Limpopo Province of South Africa

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336370292 An exploration of the 2016 Violent Protests in Vuwani, Limpopo Province of South Africa Article in Man in India · November 2018 CITATION READS 1 336 2 authors: Vongani Muhluri Nkuna Kgothatso B. Shai University of Limpopo University of Limpopo 3 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION 28 PUBLICATIONS 47 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: ANC's Political Theology View project South Africa's Foreign Policy Changes and Challenges in the Fourth Industrial Revolution View project All content following this page was uploaded by Vongani Muhluri Nkuna on 09 October 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. AN EXPLORATION OF THE 2016 VIOLENT PROTESTS... Man In India, 98 (3-4) : 425-436 © Serials Publications AN EXPLORATION OF THE 2016 VIOLENT PROTESTS IN VUWANI, LIMPOPO PROVINCE OF SOUTH AFRICA Vongani M. Nkuna* and Kgothatso B. Shai** Abstract: In the recent past, South Africa have witnessed a wave of community protests which have been attributed to a number of factors. Limpopo Province of South Africa also had a fair share of violent protests in several areas. However, protests in other areas except Vuwani have received limited media coverage, which in turn resulted in scant scholarly attention. This is to say that the community protests in Vuwani and the surrounding areas have dominated the public discourse due to the scale of violence that they produced. Despite this, the causes of the 2016 community protests in Vuwani have not been uniformly understood and this unfortunate development resulted in disastrous interventions by different stakeholders including the government. -

20 Years of Building a Competitive South Africa

CELEBRATING 20 YEARS OF BUILDING A COMPETITIVE SOUTH AFRICA BRAND SOUTH AFRICA ANNUAL REPORT 2013 | 2014 CELEBRATING 20 YEARS OF BUILDING A COMPETITIVE SOUTH AFRICA ABOUT BRAND SOUTH AFRICA Brand South Africa was established in August 2002 to help create a positive and compelling brand image for South Africa and to build the reputation of the country. Its overall mandate is to build South Africa’s nation brand reputation in order to improve the country’s global competitiveness. The primary objective of Brand South Africa is to develop and implement a proactive reputation management and brand strategy that will create a positive and unified image of South Africa. Brand South Africa strives to build pride and patriotism amongst South Africans and to promote investment and tourism, through the alignment of messaging and the building of a consolidated brand image for the country. KEY FOCUS INTERNATIONAL MARKETING AND MOBILISATION Brand South Africa’s international campaigns focus on the needs of investors in South Africa, exporters, and global South Africans. It aims to increase familiarity and knowledge of South Africa as a viable, world-class and profitable business destination in targeted international trade, investment and tourism markets. These key markets include China, India, the United States of America (USA), the United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Brazil and Russia. Targeted advertising campaigns, through broadcast, print and online media as well as other traditional marketing techniques, are used to raise awareness of all that South Africa has to oer to the international investor. Brand South Africa also engages with the global media, through initiatives such as the Media Club South Africa website and inbound and outbound media tours, to improve perceptions about South Africa in the key markets. -

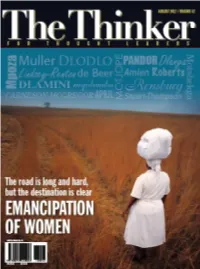

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women. -

Report of the 54Th National Conference Report of the 54Th National Conference

REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE CONTENTS 1. Introduction by the Secretary General 1 2. Credentials Report 2 3. National Executive Committee 9 a. Officials b. NEC 4. Declaration of the 54th National Conference 11 5. Resolutions a. Organisational Renewal 13 b. Communications and the Battle of Ideas 23 c. Economic Transformation 30 d. Education, Health and Science & Technology 35 e. Legislature and Governance 42 f. International Relations 53 g. Social Transformation 63 h. Peace and Stability 70 i. Finance and Fundraising 77 6. Closing Address by the President 80 REPORT OF THE 54TH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1 INTRODUCTION BY THE SECRETARY GENERAL COMRADE ACE MAGASHULE The 54th National Conference was convened under improves economic growth and meaningfully addresses the theme of “Remember Tambo: Towards inequality and unemployment. Unity, Renewal and Radical Socio-economic Transformation” and presented cadres of Conference reaffirmed the ANC’s commitment to our movement with a concrete opportunity for nation-building and directed all ANC structures to introspection, self-criticism and renewal. develop specific programmmes to build non-racialism and non-sexism. It further directed that every ANC The ANC can unequivocally and proudly say that we cadre must become activists in their communities and emerged from this conference invigorated and renewed drive programmes against the abuse of drugs and to continue serving the people of South Africa. alcohol, gender based violence and other social ills. Fundamentally, Conference directed every ANC We took fundamental resolutions aimed at radically member to work tirelessly for the renewal of our transforming the lives of the people for the better and organisation and to build unity across all structures. -

Keynote Address Delivered by the President of the Republic, His

Modiri Molema Road dpwrt Old Parliament Complex Provincial Head Office Department: Mmabatho, 2735 Public Works; Roads and Transport Private Bag X 2080, Mmabatho, 2735 North West Provincial Government Tel.: +27 (18) 388 1435 Republic of South Africa Fax: +27 (18) 387 5155 Website: www.nwpg.gov.za/public works Keynote address delivered by the President of the Republic, His Excellency, Jacob Zuma, at the 33rd Anniversary of the Soweto Student Uprising and the National Youth Day, Hunterfield Stadium, Katlehong, Ekurhuleni, June 16 2009 Date: Tuesday, June 16, 2009 • Programme Director; • Minister in the Presidency responsible for youth development, Mr Collins Chabane; • Ministers and Deputy Ministers; • Premier of Gauteng, Ms Nomvula Mokonyane and all MEC's present; • Executive Mayor of Ekurhuleni, Councillor Ntombi Mekgwe; • Chairperson of the National Youth Development Agency, Andile Lungisa and all Board Members; • Members of various youth formations; • Distinguished guests; • Mphakathi wase-Kathlehong, Siyanibingelela nonke, Dimacheroni, Dumelang! 33 years ago today, the young people of our country made untold sacrifices so that we could be free. Some gave up the relative comfort of home and went to foreign lands, while others ended up languishing in prison, in pursuit of liberation. Today we correctly celebrate that resounding voice of young people, which refused to be silenced in the face of bullets and torture. It is appropriate that we commemorate Youth Day under the appropriate theme: "Celebrating a Vibrant Youth Voice". The South African youth have never been silent, and have always been active participants in the life of this nation. They have always been actively involved in aspects, political, social and economic. -

State of the Nation Address Insert in the New

Friday, 10 February 2012 www.thenewage.co.za Brought to you by the Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) STATE OF THE NATION ADDRESS President Jacob Zuma 2011: A year of action Ricky Naidoo tion of the National Development 30 000 artisan s created further Most of these focus on procure- initiating patients on antiretrovi- u pgrading p rogramme has exce- term on the AU p eace and s ecu- Plan by the National Planning impetus for job creation. ment-related irregularities, as it ral treatment increased from 495 eded its target by providing ser- rity c ouncil. South Africa also IN HIS S tate of the N ation speech Commission in the Presidency. In the area of c ooperative is a major priority for the govern- to 2 948. A landmark achievement vices to 52 383 sites against a assumed the chair of the South- last year, President Jacob Zuma Job creation, one of the g ov- g overnance, cooperation with ment to deal with corruption in for government is the 50% reduc- target of 27 054 sites. ern African Development Com- declared: “Our goal is clear. We ernment’s key priorities, remains provincial administrations imp- procurement and to ensure better tion in mother-child transmission The Housing Development munity o rgan on p olitics, d efence want to have a country where mil- pivotal . In this regard, large-scale roved considerably because of value for money. A c ommission f]?@MY\kn\\e)''/Xe[)'('% Agency is now fully opera- and s ecurity and the Presidential lions more South Africans have projects such as electricity plants, regular meetings of the President, of i nquiry into the a rms d eal was In the area of rural development tional. -

Zuma's Cabinet Reshuffles

Zuma's cabinet reshuffles... The Star - 14 Feb 2018 Switch View: Text | Image | PDF Zuma's cabinet reshuffles... Musical chairs reach a climax with midnight shakeup LOYISO SIDIMBA [email protected] HIS FIRST CABINET OCTOBER 2010 Communications minister Siphiwe Nyanda replaced by Roy Padayachie. His deputy would be Obed Bapela. Public works minister Geoff Doidge replaced by Gwen MahlanguNkabinde. Women, children and people with disabilities minister Noluthando MayendeSibiya replaced by Lulu Xingwana. Labour minister Membathisi Mdladlana replaced by Mildred Oliphant. Water and environmental affairs minister Buyelwa Sonjica replaced by Edna Molewa. Public service and administration minister Richard Baloyi replaced by Ayanda Dlodlo. Public enterprises minister Barbara Hogan replaced by Malusi Gigaba. His deputy became Ben Martins. Sport and recreation minister Makhenkesi Stofile replaced by Fikile Mbalula. Arts and culture minister Lulu Xingwana replaced by Paul Mashatile. Social development minister Edna Molewa replaced by Bathabile Dlamini. OCTOBER 2011 Public works minister Gwen MahlanguNkabinde and her cooperative governance and traditional affairs counterpart Sicelo Shiceka are axed while national police commissioner Bheki Cele is suspended. JUNE 2012 Sbu Ndebele and Jeremy Cronin are moved from their portfolios as minister and deputy minister of transport respectively Deputy higher education and training minister Hlengiwe Mkhize becomes deputy economic development minister, replacing Enoch Godongwana. Defence minister Lindiwe Sisulu moves to the Public Service and Administration Department, replacing the late Roy Padayachie, while Nosiviwe MapisaNqakula moves to defence. Sindisiwe Chikunga appointed deputy transport minister, with Mduduzi Manana becoming deputy higher education and training minister. JULY 2013 Communications minister Dina Pule is fired and replaced with former cooperative government and traditional affairs deputy minister Yunus Carrim. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA March Vol. 645 Pretoria, 8 2019 Maart No. 42288 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 42288 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 42288 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 8 MARCH 2019 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Eastern Cape / Oos-Kaap ................................................................................................................. 13 Free State / Vrystaat ........................................................................................................................ 13 KwaZulu-Natal ................................................................................................................................ 13 North West / Noordwes ..................................................................................................................... 13 Northern Cape / Noord-Kaap ............................................................................................................ -

South Africa Country Report BTI 2012

BTI 2012 | South Africa Country Report Status Index 1-10 7.34 # 26 of 128 Political Transformation 1-10 7.75 # 24 of 128 Economic Transformation 1-10 6.93 # 33 of 128 Management Index 1-10 6.12 # 28 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2012. The BTI is a global assessment of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economy as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — South Africa Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. © 2012 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2012 | South Africa 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 50.0 HDI 0.619 GDP p.c. $ 10570 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.4 HDI rank of 187 123 Gini Index 57.8 Life expectancy years 52 UN Education Index 0.705 Poverty3 % 35.7 Urban population % 61.7 Gender inequality2 0.490 Aid per capita $ 21.8 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2011. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The period under review covers almost the first two years of President Zuma’s term in office as the president of South Africa. The African National Congress (ANC) won the nation’s fourth democratic elections in April 2009 with an overwhelming majority.