Unigov: the Indianapolis Response to Urban Sprawl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

Executive Session Agenda Indianapolis-Marion County Public

Executive Session Agenda Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library Notice Of An Executive Session November 26, 2018 Library Board Members are Hereby Notified That An Executive Session Of the Board Will Be Held At The Franklin Road Branch Library 5550 South Franklin Road, 46239 At 6:00 P.M. For the Purpose Of Considering The Following Agenda Items Dated This 21st Day of November, 2018 JOANNE M. SANDERS President of the Library Board -- Executive Session Agenda-- 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call Executive Session Agenda pg. 2 3. Discussion a. Pursuant to IC 5-14-1.5-6.1(b)(6), to receive information concerning an individual’s alleged misconduct, and to discuss, before a determination, the individual’s status as an employee. 4. Adjournment Library Board Meeting Agenda Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library Notice Of The Regular Meeting November 26, 2018 Library Board Members Are Hereby Notified That The Regular Meeting Of The Board Will Be Held At The Franklin Road Library Branch 5550 S. Franklin Road At 6:30 P.M. For The Purpose Of Considering The Following Agenda Items Dated This 21st Day Of November, 2018 JOANNE M. SANDERS President of the Library Board -- Regular Meeting Agenda -- 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call Library Board Meeting Agenda pg. 2 3. Branch Manager’s Report – Jill Wetnight, Franklin Road Branch Manager, will provide an update on their services to the community. (enclosed) 4. Public Comment and Communications a. Public Comment The Public has been invited to the Board Meeting. Hearing of petitions to the Board by Individuals or Delegations. -

'08 Primary Forgery Brings Probe

V17, N8 Sunday, Oct. 9, 2011 ‘08 primary forgery brings probe Fake signatures on Clinton, Obama petitions in St. Joe By RYAN NEES Howey Politics Indiana ERIN BLASKO and KEVIN ALLEN South Bend Tribune SOUTH BEND — The signatures of dozens, if not hundreds, of northern Indiana residents were faked on petitions used to place presidential candidates on the state pri- mary ballot in 2008, The Tribune and Howey Politics Indiana have revealed in an investigation. Several pag- es from petitions used to qualify Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama Then U.S. Sen. Hillary Clinton signs an autograph while touring Allison Transmis- for the state’s sion in Speedway. She almost didn’t qualify for the Indiana ballot for the 2008 pri- Democratic mary, which she won by less than 1 percent over Barack Obama. President Obama primary contain is shown here at Concord HS in Elkhart. (HPI Photos by Brian A. Howey and Ryan names and signa- Nees) tures that appear to have been candidate Jim Schellinger. The petitions were filed with the copied by hand from a petition for Democratic gubernatorial Continued on page 3 Romney by default? By CHRIS SAUTTER WASHINGTON - Barack Obama has often been described as lucky on his path to the presidency. But Mitt Romney is giving new meaning to the term “political luck,” as one Re- “A campaign is too shackley for publican heavyweight after another someone like me who’s a has decided against joining the current field of GOP candidates for maverick, you know, I do go president. Yet, the constant clamor rogue and I call it like I see it.” for a dream GOP candidate has ex- - Half-term Gov. -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 6 Number 1 2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy L. Draeger-Williams, Archaeologist Wade T. Tharp, Archaeologist Rachel A. Sharkey, Records Check Coordinator Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D. Amy L. Johnson Cathy A. Carson Editorial Assistance: Cathy Draeger-Williams Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. The U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service is gratefully acknow- ledged for their support of Indiana archaeological research as well as this volume. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. This publication has been funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service‘s Historic Preservation Fund administered by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. In addition, the projects discussed in several of the articles received federal financial assistance from the Historic Preservation Fund Program for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the State of Indiana. -

Indypl Shared System, 2018-19

INDYPL SHARED SYSTEM, 2018-19 Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory School Cardinal Ritter High School 2801 West 86th Indianapolis, IN 46268 3360 West 30th St Indianapolis, IN 46222 (317) 524-7050 317-924-4333 http://brebeuflibrary.blogspot.com/ www.cardinalritter.org Site code: BRE Site code: CRI School type: High school School type: High school Karcz, Charity, School library manager Jessen, Elizabeth, School library manager [email protected] [email protected] Russell, Suzanne, Assistant Library Manager Cathedral High School [email protected] 5225 E. 56th St. Indianapolis, IN 46226 317-542-1481 x 389 Building Blocks Academy http://www.cathedral-irish.org/page.cfm?p=26 3515 N. Washington Blvd, Indianapolis, IN 46205 (317) 921-1806 Site code: CHS https://www.buildingblocksacademy-bba.com/ School type: High school Site code: BBA Cataldo, Alannah, Library assistant School type: Elementary [email protected] Burksbell, Wanda, School library manager Herron, Jennifer, School library manager [email protected] [email protected] Jewish Community Library Central Catholic School Jewish Federation of Greater Indianapolis 1155 Cameron Street Indianapolis, IN 46203 6705 Hoover Road, Indianapolis, IN 46260 (317) 783-7759 317-726-5450 Site code: CCS https://www.jewishindianapolis.org/ School type: Elementary Site code: BJE Mendez, Theresa, School library manager Library type: Special [email protected] Marcia Goldstein, Library Manager Christel House Academy South [email protected] 2717 South East Street Indianapolis, IN -

Greenwood (Indianapolis), Indiana Indianapolis’ Southside a Modern Small Town

BUSINESS CARD DIE AREA 225 West Washington Street Indianapolis, IN 46204 (317) 636-1600 simon.com Information as of 5/1/16 Simon is a global leader in retail real estate ownership, management and development and an S&P 100 company (Simon Property Group, NYSE:SPG). GREENWOOD (INDIANAPOLIS), INDIANA INDIANAPOLIS’ SOUTHSIDE A MODERN SMALL TOWN Greenwood Park Mall is the only regional mall serving the southern suburbs of Indianapolis including Greenwood, a city of 55,000 people in Johnson County, Indiana. — The market is comprised predominantly of middle to upper-middle income families. — Johnson County is the third fastest-growing county in Indiana. — With its location just 12 miles south of Indianapolis, Greenwood provides the perfect combination of a small-town atmosphere with the conveniences of a bustling modern retail hub. A GATHERING SPOT Greenwood Park Mall is the premier shopping, dining, and entertainment destination on the south side of Indianapolis in Greenwood, Indiana. — The center offers trendy fashion brands and acts as a meeting place for the neighborhoods nearby. — Popular hot spots include Bar Louie and Kumo Japanese Steakhouse and Hibachi Bar. — The signature Summer Concert Series at Greenwood Park Mall brings brands and communities together. This popular event is open to the public, draws both regional and national acts, and has an average attendance of 800 guests. BY THE NUMBERS Anchored by Five Major Retailers Von Maur, Macy’s, JCPenney, Sears, Dick’s Sporting Goods Square Footage Greenwood Park Mall spans 1,288,000 square feet. Single Level Boasting more than 150 specialty stores. Entertainment Regal Greenwood Stadium 14 & RXP IN GOOD COMPANY Distinctive. -

Black History News & Notes

BLACK HISTORY NEWS & NOTES INDIANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY February, 1982 No. 8 ) Black History Now A Year-round Celebration A new awareness of black history was brought forth in 1926 when Carter Woodson in augurated Negro History Week. Since that time the annual celebration of Afro-American heritage has grown to encompass the entire month of February. Now, with impetus from concerned individuals statewide, Indiana residents are beginning to witness what hope fully will become a year-round celebration of black history. During the weeks and months immediately ahead a number of black history events have been scheduled. The following is a description of some of the activities that will highlight the next three months. Gaines to Speak Feb. 2 8 An Afro-American history lecture by writer Ernest J. Gaines on February 28 is T H E A T E R Indiana Av«. being sponsored by the Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library (I-MCPL). Gaines BIG MIDNITE RAMBLE is the author of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and several other works ON OUR STAGE pertaining to the black experience. The lecture will be held at 2:00 P.M. at St. Saturday Night Peter Claver Center, 3110 Sutherland Ave OF THIS WEEK nue. Following the event, which is free DECEMBER 15 1UW l\ M. and open to the public, Gaines will hold Harriet Calloway an autographing session. Additional Black QUEEN OF HI DE HO History Month programs and displays are IN offered by I-MCPL. For further informa tion call (317) 269-1700. DIXIE ON PARADE W ITH George Dewey Washington “Generations” Set for March Danny and Eddy FOUH PENNIES COOK and BROWN A national conference will be held JENNY DANCER FLORENCE EDMONDSON in Indianapolis March 25-27 focusing on SHORTY BURCH FRANK “Red” PERKINS American family life. -

Enter Wayne Gretzky Wanted Him in Its League, and Potentially Scuttle the Merger Impasse and the Beer Boycott Negotiations

nearly folded in late 1977, but managed to play out the financially. Realistically, the WHA knew it would not season. The Indianapolis Racers were close to failure in likely survive to see an eighth season, while the NHL mid-1977 but held on for another season with new owner saw some value in taking in the WHA’s strongest teams. Nelson Skalbania leading a group of investors. The When not playing games of brinksmanship, the Racers were constantly on the brink of collapse for most negotiations pressed forward. Fourteen of the 17 NHL of the 1977-78 season, but Skalbania was willing to incur teams needed to approve merger, but five of the teams losses for possible gains in the near future through a sale consistently voted against merger in any form. or buy-out should the merger go through. Essentially, the negotiations centered on winning over Both Cincinnati and Birmingham played to small two votes from the anti-merger subset to accumulate the home crowds and were struggling to stay solvent, but necessary 14 approvals. with the backing of its wealthy owners (DeWitt and The WHA needed a better bargaining position, and Heekin in Cincinnati, Bassett in Birmingham), both it found one: a skinny high-school senior named Wayne teams could survive the losses in the short term. The Gretzky. The prodigy had drawn attention and a level of Stingers might have succeeded in the NHL, but after fame as early as 1971, and by 1978, had shown he was 1977, the NHL did not want Cincinnati, and DeWitt and clearly superior to his Junior mates, and ready for better Heekin were willing to take the buyout if and when the competition. -

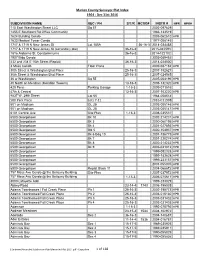

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31St 2016

Marion County Surveyor Plat Index 1964 - Dec 31st 2016 SUBDIVISION NAME SEC / PH S/T/R MCSO# INSTR # HPR HPR# 110 East Washington Street LLC Sq 57 2002-097629 1455 E Southport Rd Office Community 1986-133519 1624 Building Condo 2005-062610 HPR 1633 Medical Tower Condo 1977-008145 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St Lot 185A 36-16-3 2014-034488 1717 & 1719 N New Jersey St (secondary plat) 36-16-3 2015-045593 1816 Alabama St. Condominiums 36-16-3 2014-122102 1907 Bldg Condo 2003-089452 232 and 234 E 10th Street (Replat) 36-16-3 2014-024500 3 Mass Condo Floor Plans 2009-087182 HPR 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-182627 30th Street & Washington Blvd Place 25-16-3 2007-024565 36 w Washington Sq 55 2005-004196 HPR 40 North on Meridian (Meridian Towers) 13-16-3 2006-132320 HPR 429 Penn Parking Garage 1-15-3 2009-071516 47th & Central 13-16-3 2007-103220 HPR 4837 W. 24th Street Lot 55 1984-058514 500 Park Place Lots 7-11 2016-011908 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005146 HPR 501 on Madison OL 25 2003-005147 HPR 6101 Central Ave Site Plan 1-16-3 2008-035537 6500 Georgetown Bk 10 2002-214231 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 3 2000-060195 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 4 2001-027893 HPR 6500 Georgetown Blk 5 2000-154937 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 6 Bdg 10 2001-186775 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 7 2001-220274 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 8 2002-214232 HPR 6500 Georgetown Bk 9 2003-021012 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-092328 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-183628 HPR 6500 Georgetown 1999-233157 HPR 6500 Georgetown 2001-055005 HPR 6500 Georgetown Replat Block 11 2004-068672 HPR 757 Mass Ave -

From Social Welfare to Social Control: Federal War in American Cities, 1968-1988

From Social Welfare to Social Control: Federal War in American Cities, 1968-1988 Elizabeth Kai Hinton Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2012 Elizabeth Kai Hinton All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Social Welfare to Social Control: Federal War in American Cities, 1968-1988 Elizabeth Hinton The first historical account of federal crime control policy, “From Social Welfare to Social Control” contextualizes the mass incarceration of marginalized Americans by illuminating the process that gave rise to the modern carceral state in the decades after the Civil Rights Movement. The dissertation examines the development of the national law enforcement program during its initial two decades, from the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, which established the block grant system and a massive federal investment into penal and juridical agencies, to the Omnibus Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, which set sentencing guidelines that ensured historic incarceration rates. During this critical period, Presidential Administrations, State Departments, and Congress refocused the domestic agenda from social programs to crime and punishment. To challenge our understanding of the liberal welfare state and the rise of modern conservatism, “From Social Welfare to Social Control” emphasizes the bipartisan dimensions of punitive policy and situates crime control as the dominant federal response to the social and demographic transformations brought about by mass protest and the decline of domestic manufacturing. The federal government’s decision to manage the material consequences of rising unemployment, subpar school systems, and poverty in American cities as they manifested through crime reinforced violence within the communities national law enforcement legislation targeted with billions of dollars in grant funds from 1968 onwards. -

Geology for Environmental Planning . in Marion County

GEOLOGY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING . GEOLOGY--:~ .\RY IN MARION COUNTY, INDIANA SURVEY Special Report 19 c . 3 State of)pdiana Department of N'.atural Resources GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL STAFF OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY JOHN B. PATION, State Geologist MAURICE E. BIGGS, Assistant State Geologist MARY BETH FOX, Mineral Statistician COAL AND INDUSTRIAL MINERALS SECTION GEOLOGY SECTION DONALD D. CARR, Geologist and Head ROBERT H. SHAVER, Paleontologist and Head CURTIS H. AULT, Geologist and Associate Head HENRY H. GRAY, Head Stratigrapher PEl-YUAN CHEN, Geologist N. K. BLEUER, Glacial Geologist DONALD L. EGGERT, Geologist EDWIN J. HARTKE, Environmental Geologist GORDON S. FRASER, Geologist JOHN R. HILL, Glacial Geologist DENVER HARPER, Geologist CARL B. REXROAD, Paleontologist WALTER A. HASENMUELLER, Geologist NELSON R. SHAFFER, Geologist GEOPHYSICS SECTION PAUL IRWIN, Geological Assistant MAURICE E. BIGGS, Geophysicist and Head ROBERT F. BLAKELY, Geophysicist JOSEPH F. WHALEY, Geophysicist DRAFTINGANDPHOTOGRAPHYSECTION JOHN R. HELMS, Driller WILLIAM H. MORAN, Chief Draftsman and Head SAMUEL L. RIDDLE, Geophysical Assistant RICHARDT. HILL, Geological Draftsman ROGER L. PURCELL, Senior Geological Draftsman PETROLEUM SECTION GEORGE R. RINGER, Photographer G. L. CARPENTER, Geologist and Head WILBUR E. STALIONS, Artist-Draftsman ANDREW J. HREHA, Geologist BRIAN D. KEITH, Geologist EDUCATIONAL SERVICES SECTION STANLEY J. KELLER, Geologist R. DEE RARICK, Geologist and Head DAN M. SULLIVAN, Geologist JAMES T. CAZEE, Geological Assistant -

Official Bank of the Buffalo Sabres

ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING ROUTING JOB # 13-FNC-257 PROJECT: Sabres Yearbook Ad DATE: September 6, 2013 5:16 PM SIZE: 8.375” x 10.875” PROD BY: plh VERSION: 257_SabresProgramAd_vM ROLE STAFF INITIALS DATE/TIME ROLE STAFF INITIALS DATE/TIME ROLE STAFF INITIALS DATE/TIME PROOF AD AE CD PA AC GCD CW PM WHEN PRINTING, SELECT “MARKS AND BLEED.” THEN SELECT “PAGE INFORMATION” AND “INCLUDE SLUG AREA.” ® OFFICIAL BANK OF THE BUFFALO SABRES MAKE GREAT MEMORIES.Invest today for the goals of tomorrow. First Niagara Bank, N.A. visit us at firstniagara.com 257_SabresProgramAd_vM.indd 1 9/6/13 5:37 PM Table of Contents > > > > personnel | Sabres Personnel | | Record Book | Allaire, J.T. ...................................................................................................... 19 Record by Day/Month ..............................................................................179 Babcock, George ........................................................................................ 22 Regular Season Overtime Goals ............................................................188 Benson, Cliff .................................................................................................. 11 Sabres Streaks ............................................................................................184 Black, Theodore N. .........................................................................................8 Season Openers ........................................................................................186