18Th Century Pietism in Bach's Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

Introduction

Copyright © Thomas Braatz, 20071 Introduction This paper proposes to trace the origin and rather quick demise of the Andreas Stübel Theory, a theory which purportedly attempted to designate a librettist who supplied Johann Sebastian Bach with texts and worked with him when the latter composed the greater portion of the 2nd ‘chorale-cantata’ cycle in Leipzig from 1724 to early 1725. It was Hans- Joachim Schulze who first proposed this theory in 1998 after which it encountered a mixed reception with Christoph Wolff lending it some support in his Bach biography2 and in his notes for the Koopman Bach-Cantata recording series3, but with Martin Geck4 viewing it rather less enthusiastically as a theory that resembled a ball thrown onto the roulette wheel and having the same chance of winning a jackpot. 1 This document may be freely copied and distributed providing that distribution is made in full and the author’s copyright notice is retained. 2 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (Norton, 2000), (first published as a paperback in 2001), p. 278. 3 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Leipzig church cantatas: the chorale cantata cycle (II:1724-1725)’ in The Complete Cantatas volumes 10 and 11 as recorded by Ton Koopman and published by Erato Disques (Paris, France, 2001). 4 Martin Geck, Bach: Leben und Werk, (Hamburg, 2000), p. 400. 1 Andreas Stübel Andreas Stübel (also known as Stiefel = ‘boot’) was born as the son of an innkeeper in Dresden on December 15, 1653. In Dresden he first attended the Latin School located there. Then, in 1668, he attended the Prince’s School (“Fürstenschule”) in Meißen. -

Ctspubs Brochure Nov 2005

THE MUSIC OF CLAUDE T. SMITH CONCERT BAND WORKS ENJOY A CD RECORDING CTS = Claude T. Smith Publications WJ = Wingert-Jones HL = Hal Leonard TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER TITLE GRADE PUBLISHER $1 OF THE MUSIC OF 7.95 each Acclamation..............................................................5 ..............Kalmus Intrada: Adoration and Praise ..................................4 ................CTS All 6 for Across the Wide Missouri (Concert Band) ................3..................WJ Introduction and Caccia............................................3 ................CTS $60 Affirmation and Credo ..............................................4 ................CTS Introduction and Fugato............................................3 ................CTS Claude T. Smith Allegheny Portrait ....................................................4 ................CTS Invocation and Jubiloso ............................................2 ..................HL Allegro and Intermezzo Overture ..............................3 ................CTS Island Fiesta ............................................................3 ................CTS America the Beautiful ..............................................2 ................CTS Joyance....................................................................5..................WJ CLAUDE T. SMITH: CLAUDE T. SMITH: American Folk Trilogy ..............................................3 ................CTS Jubilant Prelude ......................................................4 ..................HL A SYMPHONIC PORTRAIT -

LUTHERAN Bach Cantata Sunday

LUTHERAN ACADEMY & FESTIVAL Bach Cantata Sunday The Eighth Sunday after Pentecost | Sunday, 14 July 2013 Service of Holy Communion Bach Cantata Sunday + Eighth Sunday after Pentecost + 14 July 2013 — 10:30AM Lutheran Summer Music Academy and Festival Today’s Texts It is easy to miss the shocking nature of this morning's parable if we think that this story only teaches us to imitate the Samaritan. The parable says so much more about God, our relationship to God, and the lengths to which God will go to reach out to us. Through the image of the Samaritan, Jesus lifts up a surprising rescuer as an image of our God who relentlessly cares for those in need. Could it be that we are meant to identify not with the Samaritan or even the lawyer to whom Jesus speaks the parable, but rather with the man who is hopeless and left for dead? Could it be that Christ is the good Samaritan who embraces us with the tender compassion of God? Jesus is not just giving us a comfortable morality tale reminding us to be nice, helpful, generous people. Instead Jesus is proclaiming the good news of the kingdom. God's grace comes to us through the cross, and our baptism into Jesus' death and resurrection. God's grace comes to us even—and especially—when we are at our worst, left for dead, bleeding and dying in life's many ditches. Even when we cannot or will not cry out, mercy and grace come into our lives through Jesus. This powerful message of Christ's death and resurrection is reinforced in Bach’s Cantata #4, Christ lag in Todesbanden. -

Johann Sebastian Bach's Kreuzstab Cantata

Johann Sebastian Bach’s Kreuzstab Cantata (BWV 56): Identifying the Emotional Content of the Libretto Georg Corall University of Western Australia Along with numerous other music theorists of the eighteenth century, Johann Joachim Quantz compares an expressive musical performance to the delivery of a persuasive speech by a distinguished orator. For a successful rhetorical delivery of the music of that period, however, today’s musicians not only need to study the score of a work, but they also need to analyse the words of the vocal parts. In the present case study, Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantata BWV 56, generally known as the Kreuzstab Cantata, will be investigated in view of its libretto’s emotional message, and how it should affect an audience. The secondary literature, which generally ties an understanding of suffering, cross-bearing and an almost suicidal component to the anonymous poet’s text, will be reviewed. In particular the term Kreuzstab, its meaning, and its emotional affiliation will be scrutinized. The Doctrine of the Affections (Affektenlehre) and the Doctrine of the Musical-Rhetorical Figures (Figurenlehre) both provide modern-day performers with the necessary tools for a historically informed performance of the music of Bach’s time and will help to identify the emotions of Bach’s work. Informed by these doctrines, as well as through the distinct definition of the term Kreuzstab, the new understanding of Bach’s Cantata BWV 56 will require modern-day performers to contemplate a new approach in their aim of a persuasive delivery in a performance. The analysis of the words of BWV 56 certainly allows for a hopeful and happy anticipation of the salvation rather than a suicidal ‘yearning for death’. -

Document Cover Page

A Conductor’s Guide and a New Edition of Christoph Graupner's Wo Gehet Jesus Hin?, GWV 1119/39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Seal, Kevin Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 06:03:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645781 A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN?, GWV 1119/39 by Kevin M. Seal __________________________ Copyright © Kevin M. Seal 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by: Kevin Michael Seal titled: A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN, GWV 1119/39 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 3, 2020 John T Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Rex A. Woods Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

The Neumeister Collection of Chorale Preludes of the Bach Circle: an Examination of the Chorale Preludes of J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 "The eumeiN ster collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works Sara Ann Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Sara Ann, ""The eN umeister collection of chorale preludes of the Bach circle": an examination of the chorale preludes of J. S. Bach and their usage as service music and pedagogical works" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 77. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/77 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE NEUMEISTER COLLECTION OF CHORALE PRELUDES OF THE BACH CIRCLE: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CHORALE PRELUDES OF J. S. BACH AND THEIR USAGE AS SERVICE MUSIC AND PEDAGOGICAL WORKS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts Sara Ann Jones B. A., McNeese State University -

Edition Peters Sounds 21

NEW ISSUES 2018 www.editionpeters.com EDITION PETERS THE GREEN SERIES AT 150 Hidden behind the iconic green covers of Edition Peters lies a story that is fascinating and complex, at times heartbreakingly tragic, but also overwhelmingly inspirational – a story that should never be forgotten. It is told in a new documentary that is now available to watch on the Edition Peters Group YouTube channel and at www.editionpeters.com. Come and visit us to find out how Edition Peters wrote music history. Scan the code to watch the documentary now. March 2018 | Prices correct at time of going to print but subject to change PREFACE 3 Edition Peters, with its three offices in Leipzig, London and New York, has always had a truly international approach to music. Continuing the tradition, 2018 sees the company launch many projects sourced from a richly diverse range of cultures and countries. We begin with the launch of The Silk Road Series, a groundbreaking co-publication with our partners in China, the Central Conservatoire of Music Press in Beijing. Eight of China’s leading contemporary composers have contributed major works to the series, inspired by the Silk Road. And fittingly, Leipzig – where the Peters story began in 1800 – is now on the New Silk Road (“Belt and Road”). Leipzig provides the powerful music included in our Peters East German Library 1949 – 1990. The years in which Germany, and the publishing house itself, were divided between East and West form an important chapter in the company’s story. The output of composers from the East German firm – then known as VEB Edition Peters, Leipzig – forms a unique and valuable part of the company’s identity and, more widely, of European cultural history, making this repertoire well worth rediscovering. -

Bach Christmas Oratorio Prog Notes

Johann Sebastian Bach Christmas Oratorio Programme Notes Johann Sebastian Bach’s Christmas Oratorio was composed in 1734. The title page of the printed libretto, prepared for the congregation, notes “Oratorio performed over the holy festival of Christmas in the two chief churches in Leipzig.” The oratorio was divided into six parts, each part to be performed at one of the six services held during the Lutheran celebration of the Twelve Nights of Christmas. Parts I, II, IV and VI were each performed twice, at St. Thomas and St. Nicholas in alternate morning and afternoon services. Parts III and V, written for days of lesser significance in the festival, were performed only once at St. Nicholas. The music would have served as the “principal music” for the day, replacing the cantata that would otherwise have been performed. The structure of the Christmas Oratorio is similar to that of Bach’s Passions: Bach presents a dramatic rendering of a biblical text, largely in the form of secco recitative (recitative with simple continuo accompaniment) sung by an Evangelist, and adds to it comments and reflections of both an individual and congregational nature, in the form of arias, choruses, and chorales. The biblical text in question is the story of the birth of Jesus through to the arrival of the three Wise Men, drawn from the Gospels according to Luke and Matthew. The narrative is by its very nature less dramatic than that of the Passions, so Bach introduces a number of arioso passages: accompanied recitatives in which the spectator enters the story. The bass soloist, for example, speaks to the shepherds, and the alto to Herod and to the Wise Men, outside the narrative proper, yet intimately involved with it. -

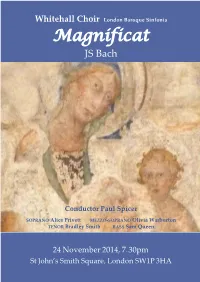

Magnificat JS Bach

Whitehall Choir London Baroque Sinfonia Magnificat JS Bach Conductor Paul Spicer SOPRANO Alice Privett MEZZO-SOPRANO Olivia Warburton TENOR Bradley Smith BASS Sam Queen 24 November 2014, 7. 30pm St John’s Smith Square, London SW1P 3HA In accordance with the requirements of Westminster City Council persons shall not be permitted to sit or stand in any gangway. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment is strictly forbidden without formal consent from St John’s. Smoking is not permitted anywhere in St John’s. Refreshments are permitted only in the restaurant in the Crypt. Please ensure that all digital watch alarms, pagers and mobile phones are switched off. During the interval and after the concert the restaurant is open for licensed refreshments. Box Office Tel: 020 7222 1061 www.sjss.org.uk/ St John’s Smith Square Charitable Trust, registered charity no: 1045390. Registered in England. Company no: 3028678. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Choir is very grateful for the support it continues to receive from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). The Choir would like to thank Philip Pratley, the Concert Manager, and all tonight’s volunteer helpers. We are grateful to Hertfordshire Libraries’ Performing Arts service for the supply of hire music used in this concert. The image on the front of the programme is from a photograph taken by choir member Ruth Eastman of the Madonna fresco in the Papal Palace in Avignon. WHITEHALL CHOIR - FORTHCOMING EVENTS (For further details visit www.whitehallchoir.org.uk.) Tuesday, 16 -

Classical Christmas

Classical Friday, Dec. 9 CHristmas 10:30am Stefan Sanders leads the BPO and Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus in this festival celebration of timeless musical treasures, including Bach’s Christmas Oratorio REPERTOIRE: and Handel’s Messiah . Rimsky-Korsakov: Suite from Christmas Eve Eric Whitacre: Winter, Naryan Padmanabha, sitar Respighi: L’Adorazione dei Magi from Trittico Botticelliano Bach: Weihnachtsoratorium, BWV 248 [Christmas Oratorio] Cantana IV: On New Year’s Day (The Feast of Circumcision) No. 36 Fallt mit Danken, fallt mit Loben (chorus) No. 38 Recitativ: Immanuel, o susses Wort ! (baritone and soprano) No. 39 Aria: Flost, mein Heiland, lost dein Namon (soprano and boy soprano) Cantata V: On the Sunday After New Year (King Herod) No. 53 Choral: Zwar ist solche Herzensstube Cantata VI: On the Feast of the Epiphany (The Adoration of Magi) No. 64 Choral: Nun said ihr wohl gerochen Emily Helenbrook, Brad Hutchings, Ayden Herried, Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus Intermission: Randol Bass: Festival Magnificat. Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus Arr. John Rutter: I saw Three Ships. Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus John Rutter: Mary’s Lullaby. Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus Adam/ John Rutter: O Holy Night. Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus Handel/ John Rutter: Joy to the World. Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus Tchaikovsky: Finale to Act 1 of The Nutcracker, Op. 71 6. Scena 7. Scena (Battle) 8. Scena 9. Waltz of the Snowflakes Women of the Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus Handel: Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah. Buffalo Philharmonic Chorus Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: “Christmas Eve” Russian Composer (1844-1908) Rimsky-Korsakov’s Opera Christmas Eve was completed in 1895. The four act libretto (text of the opera) by the composer is based on a short story by Nikolai Gogol from his collection titled “Evenings on a farm near Dikanka”, published in 1832.