Towards a Methodological Design for Evaluating Online Brand Positioning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia

THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL TRUST OF AUSTRALIA 2015 Churchill Fellowship Report by Ms Bronnie Mackintosh PROJECT: This Churchill Fellowship was to research the recruitment strategies used by overseas fire agencies to increase their numbers of female and ethnically diverse firefighters. The study focuses on the three most widely adopted recruitment strategies: quotas, targeted recruitment and social change programs. DISCLAIMER I understand that the Churchill Trust may publish this report, either in hard copy or on the internet, or both, and consent to such publication. I indemnify the Churchill Trust against loss, costs or damages it may suffer arising out of any claim or proceedings made against the Trust in respect for arising out of the publication of any report submitted to the Trust and which the Trust places on a website for access over the internet. I also warrant that my Final Report is original and does not infringe on copyright of any person, or contain anything which is, or the incorporation of which into the Final Report is, actionable for defamation, a breach of any privacy law or obligation, breach of confidence, contempt of court, passing-off or contravention of any other private right or of any law. Date: 16th April 2017 1 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. Bronnie Mackintosh. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 PROGRAMME 6 JAPAN 9 HONG KONG 17 INDIA 21 UNITED KINGDOM 30 STAFFORDSHIRE 40 CAMBRIDGE 43 FRANCE 44 SWEDEN 46 CANADA 47 LONDON, ONTARIO 47 MONTREAL, QUEBEC 50 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 52 NEW YORK CITY 52 GIRLS FIRE CAMPS 62 LOS ANGELES 66 SAN FRANCISCO 69 ATLANTA 71 CONCLUSIONS 72 RECOMMENDATIONS 73 IMPLEMENTATION AND DISSEMINATION 74 2 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. -

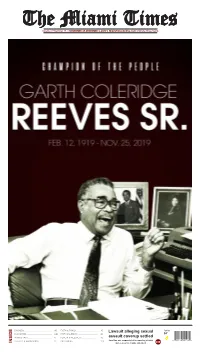

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR. -

Blessed Sacrament

Blessed Sacrament June 21, 2020 Roman Catholic Parish Blessed Sacrament Parish Directory Roman Catholic Parish 11300 North 64th Street, Scottsdale, AZ 85254 Clergy Phone: 480-948-8370 | Fax: 480-951-3844 Rev. Bryan Buenger, Parochial Administrator [email protected] | www.bscaz.org Rev. George Jingwa, Parochial Vicar Facebook: @BSScottsdale Rev. George Schroeder, Retired Deacon Jeff Strom Mass Times Senior Deacon Bob Evans Senior Deacon Jim Nazzal Bishop Olmsted has dispensed all of the faithful from the obligation to attend Sunday Mass until Administration further notice. Catholics are encouraged to make Mary Ann Bateman, Office Manager & SET Coordinator a Spiritual Communion, to pray the Rosary and Larry Cordier, Finance Manager other devotional prayers during this time. Lucille Franks, Coordinator of Parish Events Reconciliation Farah Olsen, Administrative Assistant Anne Roettger, Parish Secretary Wednesday @ 4pm Mary Ann Miller, Office Assistant Saturday @ 8:30am Liturgy Other Contact Information Mike Barta, Director of Liturgy & Music Julie McBride, Facilitator of Liturgy Preschool & Kindergarten Formation 480-998-9466 Dr. Larry Fraher, Director of Faith Formation Dr. Isabella Rice, Coordinator of Elementary RE Infant Baptism Jeremy Stafford, Coordinator of Youth Ministry Larry Fraher: ext. 216 Outreach Funeral Planning Mary Ellen Brown, Director of Engagement Julie McBride: ext. 208 Communications Sacrament Preparation Michelle Harvey, Director of Marketing & Media Larry Fraher: ext. 216 Maintenance Adults Returning to the Faith John Escajeda, Facilities Maintenance Manager Larry Fraher: ext. 216 Greg McBride, Maintenance Parish Representation John Carcanaques, Maintenance Pastoral Council President Preschool & Kindergarten Scott Bushey Heather Fraher, School Director Finance Council President Dan Mahoney Gift Shop is closed until further notice © 2020 Blessed Sacrament Roman Catholic Parish Ernest Shackleton set out on an expedition to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. -

March 2019 Newspaper

ELITE NEWS A Student Publication of Humanities III March 2019 (Volume 5) Pi Day Competition By Lorenzo Mcbean Pi Day is celebrated on March 14th (3.14) around the world. Pi (Greek letter “π”)is the symbol used in mathematics to represent a constant the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter — which is approximately 3.14159. Pi Day is an annual opportunity for math enthusiasts to recite the infinite digits of Pi. According to our HUM III Pi Day Competition contestants, the experience was ¨Fun, impressive, and nerve wracking." So I interviewed the contestants on how they prepared for the event and here are their responses: Ms Cryer: “I actually didn’t prepare a whole lot, but when I got there someone had the sheet so I stole it and memorized it really fast. The Tuesday after there was a trivia (Trivia Tuesdays) and one of the questions was ‘What were the first 5 digits of pi?’ Since I participated in Pi Day I got the question right.” (21 digits) Ms Oborne: “So, 10 minutes before the competition I studied the numbers last minute. I memorized as many as I could to the tune twinkle twinkle little star. Also, it was easier to memorize them in groups of 4. It was really impressive to see the two students winners work hard to memorize the numbers.” (27 digits) Taylor Freeman: "In Mr.Fitz's classroom we repeated the numbers over and over till it was stuck in my head. It was a fun experience.” (41 digits) Abou Dieng: “I studied a lot, and then the weekend prior to the event I reviewed it to make sure I knew it. -

“I Know That We the New Slaves”: an Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’S Yeezus

1 “I KNOW THAT WE THE NEW SLAVES”: AN ILLUSION OF LIFE ANALYSIS OF KANYE WEST’S YEEZUS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY MARGARET A. PARSON DR. KRISTEN MCCAULIFF - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2017 2 ABSTRACT THESIS: “I Know That We the New Slaves”: An Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’s Yeezus. STUDENT: Margaret Parson DEGREE: Master of Arts COLLEGE: College of Communication Information and Media DATE: May 2017 PAGES: 108 This work utilizes an Illusion of Life method, developed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001) to analyze the 2013 album Yeezus by Kanye West. Through analyzing the lyrics of the album, several major arguments are made. First, Kanye West’s album Yeezus creates a new ethos to describe what it means to be a Black man in the United States. Additionally, West discusses race when looking at Black history as the foundation for this new ethos, through examples such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nina Simone’s rhetoric, references to racist cartoons and movies, and discussion of historical events such as apartheid. West also depicts race through lyrics about the imagined Black male experience in terms of education and capitalism. Second, the score of the album is ultimately categorized and charted according to the structures proposed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001). Ultimately, I argue that Yeezus presents several unique sounds and emotions, as well as perceptions on Black life in America. 3 Table of Contents Chapter One -

Selected Personality Constructs As Correlates of Personnel Appointment, Appraisal, and Mobility in Seventh-Day Adventist Schools

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 1981 Selected Personality Constructs as Correlates of Personnel Appointment, Appraisal, and Mobility in Seventh-day Adventist Schools Merle A. Greenway Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Other Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Greenway, Merle A., "Selected Personality Constructs as Correlates of Personnel Appointment, Appraisal, and Mobility in Seventh-day Adventist Schools" (1981). Dissertations. 407. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/407 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. -

Kobena Mercer in Black Hair/Style Politics

new formations NUMBER 3 WINTER 1987 Kobena Mercer BLACK HAIR/STYLE POLITICS Some time ago Michael Jackson's hair caught fire when he was filming a television commercial. Perhaps the incident became newsworthy because it brought together two seemingly opposed news-values: fame and misfortune. But judging by the way it was reported in one black community newspaper, The Black Voice, Michael's unhappy accident took on a deeper significance for a cultural politics of beauty, style and fashion. In its feature article, 'Are we proud to be black?', beauty pageants, skin-bleaching cosmetics and the curly-perm hair-style epitomized by Jackson's image were interpreted as equivalent signs of a 'negative' black aesthetic. All three were roundly condemned for negating the 'natural' beauty of blackness and were seen as identical expressions of subjective enslavement to Eurocentric definitions of beauty, thus indicative of an 'inferiority complex'.1 The question of how ideologies of 'the beautiful' have been defined by, for and - for most of the time - against black people remains crucially important. But at the same time I want to take issue with the widespread argument that, because it involves straightening, the curly-perm hair-style represents either a wretched imitation of white people's hair or, what amounts to the same thing, a diseased state of black consciousness. I have a feeling that the equation between the curly-perm and skin-bleaching cremes is made to emphasize the potential health risk sometimes associated with the chemical contents of hair-straightening products. By exaggerating this marginal risk, a moral grounding is constructed for judgements which are then extrapolated to assumptions about mental health or illness. -

An Investigation of N-Person Prisoners' Dilemmas

An Investigation of N-person Prisoners’ Dilemmas Miklos N. Szilagyi Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 This paper is an attempt to systematically present the problem of various N-person Prisoners’ Dilemma games and some of their possible solutions. 13 characteristics of the game are discussed. The role of payoff curves, per- sonalities, and neighborhood is investigated. Experiments are performed with a new simulation tool for multi-agent Prisoners’ Dilemma games. Investigations of realistic situations in which agents have various person- alities show interesting new results. For the case of pavlovian agents the game has nontrivial but remarkably regular solutions. Examples of nonuniform distributions and mixed personalities are also presented. All solutions strongly depend on the choice of parameter values. 1. Introduction The Prisoners’ Dilemma is usually defined between two players [1] and within Game Theory which assumes that the players act rationally. Realistic investigations of collective behavior, however, require a multi- person model of the game [2] that serves as a mathematical formulation of what is wrong with human society [3]. This topic has great practical importance because its study may lead to a better understanding of the factors stimulating or inhibiting cooperative behavior within social systems. It recapitulates characteristics fundamental to almost every social intercourse. Various aspects of the multi-person Prisoners’ Dilemma have been investigated in the literature but there is still no consensus about its real meaning [4–26]. Thousands of papers have been published about the two-agent iter- ated Prisoners’ Dilemma game, a few of these are [27–30]. -

The Authenticity of a Rapper: the Lyrical Divide Between Personas

The Authenticity of a Rapper: The Lyrical Divide Between Personas and Persons by Hannah Weiner A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2014 © March 25, 2014 Hannah Weiner Acknowledgements The past year has been dedicated to listening to countless hours of rap music, researching hip hop blogs, talking to everyone who will listen about exciting ideas about Kanye West, and, naturally, writing. Many individuals have provided assistance that helped an incredible amount during the process of writing and researching for this thesis. Firstly, I am truly indebted to my advisor, Macklin Smith. This thesis would not be nearly as thorough in rap’s historical background or in hip hop poetics without his intelligent ideas. His helpfulness with drafts, inclusion of his own work in e-mails, and willingness to meet over coffee not only deepened my understanding of my own topic, but also made me excited to write and research hip hop poetics. I cannot express how much I appreciated his feedback and flexibility in working with me. I am also grateful for Gillian White’s helpfulness throughout the writing process, as well. After several office hours and meetings outside of class, she has offered invaluable insight into theories on sincerity and the “personal,” and provided me with numerous resources that helped form many of the ideas expressed in my argument. I thank my family for supporting me and offering me hospitality when the stresses of thesis writing overwhelmed me on campus. They have been supportive and a source of love and compassion throughout this process and the past 21 years, as well. -

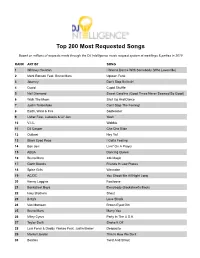

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

Maritzburg College Magazine 2018 in 2019 with Covers LO-RES

1 2 3 Nº 153 for the 2018 calendar year 4 CONTENTS Contents Days of Yore: from the College Archives 4 Governing Body 6 Staff and Staff Notes 8 Speech Day 18 Sports and Cultural Awards Ceremony 21 Prize-giving 23 Awards and Scholarships 26 National Senior Certificate Results 2018 28 Outreach 29 Leadership and Pupil Development 29 Prefects 31 Subject Departments 34 Creativity at College 47 • English Writing 47 • Afrikaanse Skryfwerk 55 • isiZulu Imibhala Yokoziqambela 60 • Art 62 Cultural and Social Activites 64 • Performing Arts 64 • Music 67 • Academic Olympiads, Displays, Expositions and Other Competitions 69 • Clubs and Societies 70 Other Activities 85 Out & About 92 House Reports 98 • 2018 Inter-House Competition 103 Boarding 104 Sport 110 Provincial and National Representatives 201 Sixth Form Photographs 202 Form Lists 207 Old Boys’ Association 212 Editor Tarryn Louch Editorial assistance, proof-reading and advertising Liz Dewes Proof-reading and editing Tony Wiblin, Gertie Landsberg, Jabulani Mhlongo, Tony Nevill Photographs Sally Upfold and College Marketing team, College Camera Club, Debbie Gademan, Matthew Marshall, Justin Waldman Design and layout Justin James Advertising Printing Colour Display Print (Pty) Ltd Physical Address: 51 College Road, Pietermaritzburg, 3201 | Postal Address: PO Box 398, Pietermaritzburg, 3200 Information and Enquiries: [email protected] School: Tel: 033 342 9376 | Fax: 033 394 2908 | Website: www.maritzburgcollege.co.za 5 DAYS OF YORE DAYS OF YORE From the College Archives 100 Years Ago 50 Years Ago Extract from College Magazine #45, dated June 1918 Extract from College Magazine #103, dated March 1969 “Our numbers are rapidly increasing, so much so that the Government has bought, for the College, the adjoining house which was occupied by the late Mr. -

State of Florida V. Demons

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE 17rH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT IN AND FOR BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA CASE#: 19-001872CF10A JUDGE: SIEGEL STATE OF FLORIDA v. JAMELL DEMONS VICTIM'S OBJECTION AND RESPONSE TO DEFENDANT'S EMERGENCY MOTION FOR VICTIM'S RELEASE FROM MEDICAL CARE AND SUPPLEMENTAL EMERGENCY MOTION FOR RELEASE FROM MEDICAL CARE VICTIM'S ELECTION OF CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS UNDER MARSY'S LAW COMES NOW, and appears the undersigned attorney on behalf of the victims in this matter, the family of Christopher Thomas, Jr., and files this Response to the Emergency Motion for Release from Medical Care and the Supplemental Emergency Motion for Release from Medical Care filed on behalf of Defendant Mr. Demons. The victims and their counsel also hereby invoke Marsy's Law, encoded in Article 1, Section 16 of the Florida Constitution. In support thereof, the family of victim Christopher Thomas, Jr., states: 1. We represent the family of victim Christopher Thomas, Jr. Marsv's Law 2. Marsy's Law is a constitutional amendment that was passed on November 26, 2018. Modeled after a similar measure in California, Marsy's Law broadens the rights of crime victims and codifies them into the Florida Constitution. • 3. Marsy's law consists of two parts: ( 1) automatically granted constitutional rights and, (2) constitutional rights a victim must elect to receive. 4. Under Article I, Section 16(b), Marsy's law is designed to, "preserve and protect the rights of crime victims to achieve justice, ensure a meaningful role throughout the criminal and juvenile justice systems for crime victims, and ensure that crime victims' rights and interests are respected and protected by law in a manner no less vigorous than protections afforded to criminal defendants and juvenile delinquents." 5.