Are Humans Inherently Killers?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Coping with CROWDING by Frans B

POPULATION GROWTH has been thought, since the time of Thomas Malthus, to produce dire consequences such as disease, scarcity and social deviancy. This dark view seemed confirmed by rodent studies. Yet little evi- dence suggests that people are similarly affected: we seem to handle large crowds quite well for the most part. Coping with CROWDING by Frans B. M. de Waal, Filippo Aureli and Peter G. Judge 76 Scientific American May 2000 Coping with Crowding Copyright 2000 Scientific American, Inc. n 1962 this magazine published a seminal But, one could argue, perhaps such a re- paper by experimental psychologist John lation is obscured by variation in national IB. Calhoun entitled “Population Density income level, political organization or some and Social Pathology.” The article opened other variable. Apparently not, at least for dramatically with an observation by the late- income. We divided the nations into three 18th-century English demographer Thomas categories—free-market, former East Block Malthus that human population growth is and Third World—and did the analysis automatically followed by increased vice and again. This time we did find one significant misery. Calhoun went on to note that al- correlation, but it was in the other direc- though we know overpopulation causes dis- tion: it showed more violent crime in the ease and food shortage, we understand virtu- least crowded countries of the former East ally nothing about its behavioral impact. Block. A similar trend existed for free-mar- This reflection had inspired Calhoun to ket nations, among which the U.S. had by conduct a nightmarish experiment. -

The Evolution of Cooperative Breeding in the African Cichlid Fish, Neolamprologus Pulcher

Biol. Rev. (2011), 86, pp. 511–530. 511 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00158.x The evolution of cooperative breeding in the African cichlid fish, Neolamprologus pulcher Marian Wong∗ and Sigal Balshine Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada (Received 14 December 2009; revised 5 August 2010; accepted 16 August 2010) ABSTRACT The conundrum of why subordinate individuals assist dominants at the expense of their own direct reproduction has received much theoretical and empirical attention over the last 50 years. During this time, birds and mammals have taken centre stage as model vertebrate systems for exploring why helpers help. However, fish have great potential for enhancing our understanding of the generality and adaptiveness of helping behaviour because of the ease with which they can be experimentally manipulated under controlled laboratory and field conditions. In particular, the freshwater African cichlid, Neolamprologus pulcher, has emerged as a promising model species for investigating the evolution of cooperative breeding, with 64 papers published on this species over the past 27 years. Here we clarify current knowledge pertaining to the costs and benefits of helping in N. pulcher by critically assessing the existing empirical evidence. We then provide a comprehensive examination of the evidence pertaining to four key hypotheses for why helpers might help: (1) kin selection; (2) pay-to-stay; (3) signals of prestige; and (4) group augmentation. For each hypothesis, we outline the underlying theory, address the appropriateness of N. pulcher as a model species and describe the key predictions and associated empirical tests. For N. -

What, If Anything, Is a Darwinian Anthropology?

JONATHAN MARKS What, if anything, is a Darwinian anthropology? Not too many years ago, I was scanning the job advertisements in anthropology and stumbled upon one for a faculty post in a fairly distinguished department in California. The ad specified that they were looking for someone who ‘studied culture from an evolutionary perspective’. I was struck by that, because it seemed to me that the alternative would be a creationist perspective, and I had never heard of anyone in this century who did that. Obviously my initial reading was incorrect. That department specifically wanted someone with a particular methodological and ideo- logical orientation; ‘evolutionary perspective’ was there as a code for something else. It has fascinated me for a number of years that Darwin stands as a very powerful symbol in biology. On the one hand, he represents the progressive aspect of science in its perpetual struggle against the perceived oppressive forces of Christianity (Larson 1997); and on the other, he represents as well the prevailing stodgy and stultified scientific orthodoxy against which any new bold and original theory must cast itself (Gould 1980). Proponents of the neutral theory (King and Jukes 1969) or of punctuated equilibria (Eldredge 1985) represented themselves as Darwinists to the outside worlds, and as anti-Darwinists to the inside world. Thus, Darwinism can be both the new and improved ideology you should bring home today, and is also the superseded Brand X ideology. That is indeed a powerful metaphor, to represent something as well as its opposite. Curiously, nobody ever told me in my scientific training that scientific progress was somehow predicated on the development of powerful metaphors. -

Human Origins Studies: a Historical Perspective

Evo Edu Outreach (2010) 3:314–321 DOI 10.1007/s12052-010-0248-7 ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Human Origins Studies: A Historical Perspective Tom Gundling Published online: 29 July 2010 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 Abstract Research into the deep history of the human within the field of paleoanthropology, but rather to identify species is a relatively young science which can be divided broad patterns and highlight a collection of “events” that into two broad periods. The first spans the century between are most germane in shaping current understanding of our the publication of Darwin’s Origin and the end of World evolutionary origin. These events naturally include the War II. This period is characterized by the recovery of the accretion of fossil material, the raw data which is the direct, first non-modern human fossils and subsequent attempts at if mute, testimony of the past. These fossil discoveries are reconstructing family trees as visual representations of the situated among technological breakthroughs, theoretical transition from ape to human. The second period, from shifts, and changes in the sociocultural context in which 1945 to the present, is marked by a dramatic upsurge in the human origins studies were conducted. It is only through quantity of research, with a concomitant increase in such a contextualized historical approach that we can truly specialization. During this time, emphasis shifted from grasp our current understanding of human origins. Foibles classification of fossil humans to paleoecology in which of the past remind us to be critical in assessing newly hominids were seen as parts of complex evolving ecosys- produced knowledge, yet simultaneously we can genuinely tems. -

Leary, C.J. 2014. Close-Range Vocal Signals Elicit a Stress Response in Male Green Treefrogs

Animal Behaviour 96 (2014) 39e48 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Animal Behaviour journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/anbehav Close-range vocal signals elicit a stress response in male green treefrogs: resolution of an androgen-based conflict * Christopher J. Leary Department of Biology, The University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS, U.S.A. article info Male courtship signals often stimulate the production of sex steroids in both female and male receivers. fi Article history: Such effects bene t signallers by increasing receptivity in females, but impose costs on signallers by Received 11 March 2014 promoting sexual behaviour and aggression in male competitors. To resolve this androgen-based conflict, Initial acceptance 24 April 2014 males should use strategies that suppress sex steroid production in rival males. In green treefrogs, Hyla Final acceptance 7 July 2014 cinerea, chorus sounds (i.e. advertisement calls from aggregates of males) are known to stimulate Published online 17 August 2014 androgen production in receiver males. Here, I examined whether males of this species counter these MS. number: A14-00205R effects by eliciting an endocrine stress response in male conspecifics during close-range vocal in- teractions. I show that corticosterone (CORT) levels were higher in males that lost vocal contests in Keywords: natural choruses compared to contest winners and nonaggressive males. Testosterone levels were also acoustic signal lower in contest losers compared to nonaggressive males, but not contest winners; dihydrotesterone challenge hypothesis levels did not differ among the three groups. Aggressive and advertisement calls were then broadcast to courtship signal glucocorticoid males in an experiment that simulated close-range vocal communication. -

Primate Aggression and Evolution: an Overview of Sociobiological and Anthropological Perspectives JAMES J

Primate Aggression and Evolution: An Overview of Sociobiological and Anthropological Perspectives JAMES J. McKENNA Attempts to explain the nature and causes of human aggression are hand icapped primarily because aggression is anything but a unitary concept. Aggression has no single etiology, no matter which mammalian species we consider or what kind of causation (developmental or evolutionary) we stress. Nevertheless, forensic psychiatrists are asked to evaluate instances of human aggression in ways that would send shivers up the spines of researchers who have been wrestling with the issue for over fifty years. This is not to say forensic psychiatry should be abolished nor to suggest be havioral scientists have not made progress in discovering causes of species aggression in genera}l and human violence in particular.2 But especially when predictive models are considered it does mean we are far from achiev ing highly reliable results.:l Particularly when one person is asked to assess the motivational state of another who has committed a serious aggressive act it becomes more evident just how much more data we need. Strangely, if a forensic psychia trist were asked to testify in a case in which, let us say, one monkey attacked another, the testimony would be based on more complete information than a case involving a human. This is because a plethora of context-specific data on nonhuman primates are available. These data illuminate a wide range of social, ecological, and endocrinological circumstances under which animals will be expected to act aggressively. Data on humans are much more complex, and sometimes they are absent altogether. -

Bringing in Darwin Bradley A. Thayer

Bringing in Darwin Bradley A. Thayer Evolutionary Theory, Realism, and International Politics Efforts to develop a foundation for scientiªc knowledge that would unite the natural and social sci- ences date to the classical Greeks. Given recent advances in genetics and evolu- tionary theory, this goal may be closer than ever.1 The human genome project has generated much media attention as scientists reveal genetic causes of dis- eases and some aspects of human behavior. And although advances in evolu- tionary theory may have received less attention, they are no less signiªcant. Edward O. Wilson, Roger Masters, and Albert Somit, among others, have led the way in using evolutionary theory and social science to produce a synthesis for understanding human behavior and social phenomena.2 This synthesis posits that human behavior is simultaneously and inextricably a result of evo- lutionary and environmental causes. The social sciences, including the study of international politics, may build upon this scholarship.3 In this article I argue that evolutionary theory can improve the realist theory of international politics. Traditional realist arguments rest principally on one of two discrete ultimate causes, or intellectual foundations. The ªrst is Reinhold Niebuhr’s argument that humans are evil. The second is grounded in the work Bradley A. Thayer is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Minnesota—Duluth. I am grateful to Mlada Bukovansky, Stephen Chilton, Christopher Layne, Michael Mastanduno, Roger Masters, Paul Sharp, Alexander Wendt, Mike Winnerstig, and Howard Wriggins for their helpful comments. I thank Nathaniel Fick, David Hawkins, Jeremy Joseph, Christopher Kwak, Craig Nerenberg, and Jordana Phillips for their able research assistance. -

Concepts Derived from the Challenge Hypothesis T ⁎ John C

Hormones and Behavior 115 (2019) 104550 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Hormones and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yhbeh Review article Concepts derived from the Challenge Hypothesis T ⁎ John C. Wingfielda, , Wolfgang Goymannb, Cecilia Jalabertc,d, Kiran K. Somac,d,e a Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA b Department of Behavioral Neurobiology, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology, Seewiesen, Germany c Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada d Djavad Mofawaghian Centre for Brain Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada e Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Challenge Hypothesis was developed to explain why and how regulatory mechanisms underlying patterns of State levels testosterone secretion vary so much across species and populations as well as among and within individuals. The Neurosteroids hypothesis has been tested many times over the past 30 years in all vertebrate groups as well as some in- Songbird vertebrates. Some experimental tests supported the hypothesis but many did not. However, the emerging con- Aggression cepts and methods extend and widen the Challenge Hypothesis to potentially all endocrine systems, and not only Testosterone control of secretion, but also transport mechanisms and how target cells are able to adjust their responsiveness to Mass spectrometry Androgens circulating levels of hormones independently of other tissues. The latter concept may be particularly important in explaining how tissues respond differently to the same hormone concentration. Responsiveness of the hy- pothalamo-pituitary-gonad (HPG) axis to environmental and social cues regulating reproductive functions may all be driven by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) or gonadotropin-inhibiting hormone (GnIH), but the question remains as to how different contexts and social interactions result in stimulation of GnRH or GnIH release. -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title How Collective Personality, Behavioral Plasticity, Information, and Fear Shape Collective Hunting in a Spider Society Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4pm302q6 Author Wright, Colin Morgan Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara How Collective Personality, Behavioral Plasticity, Information, and Fear Shape Collective Hunting in a Spider Society A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology, Evolution and Marine Biology by Colin M. Wright Committee in charge: Professor Jonathan Pruitt, Chair Professor Erika Eliason Professor Thomas Turner June 2018 The dissertation of Colin M. Wright is approved. ____________________________________________ Erika Eliason ____________________________________________ Thomas Turner ____________________________________________ Jonathan Pruitt, Committee Chair April 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my Ph.D. advisor, Dr. Jonathan Pruitt, for supporting me and my research over the last 5 years. I could not imagine having a better, or more entertaining, mentor. I am very thankful to have had his unwavering support through academic as well as personal challenges. I am also extremely thankful for all the members of the Pruitt Lab (Nick Keiser, James Lichtenstein, and Andreas Modlmeier), as well as my cohorts at both the University of Pittsburgh and UCSB that have been my closest friends during graduate school. I appreciate Dr. Walter Carson at the University of Pittsburgh for being an unofficial second mentor to me during my time there. Most importantly, I would like to thank my family, Rill (mother), Tom (father), and Will (brother) Wright. -

The Descent of Edward Wilson

prospectmagazine.co.uk http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/edward-wilson-social-conquest- earth-evolutionary-errors-origin-species/ The descent of Edward Wilson A new book on evolution by a great biologist makes a slew of mistakes The Social Conquest of Earth By Edward O Wilson (WW Norton, £18.99, May) When he received the manuscript of The Origin of Species, John Murray, the publisher, sent it to a referee who suggested that Darwin should jettison all that evolution stuff and concentrate on pigeons. It’s funny in the same way as the spoof review of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which praised its interesting “passages on pheasant raising, the apprehending of poachers, ways of controlling vermin, and other chores and duties of the professional gamekeeper” but added: “Unfortunately one is obliged to wade through many pages of extraneous material in order to discover and savour these sidelights on the management of a Midland shooting estate, and in this reviewer’s opinion this book can not take the place of JR Miller’s Practical Gamekeeping.” I am not being funny when I say of Edward Wilson’s latest book that there are interesting and informative chapters on human evolution, and on the ways of social insects (which he knows better than any man alive), and it was a good idea to write a book comparing these two pinnacles of social evolution, but unfortunately one is obliged to wade through many pages of erroneous and downright perverse misunderstandings of evolutionary theory. In particular, Wilson now rejects “kin selection” (I shall explain this below) and replaces it with a revival of “group selection”—the poorly defined and incoherent view that evolution is driven by the differential survival of whole groups of organisms. -

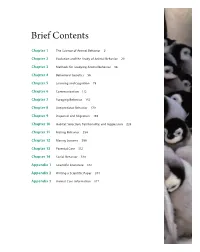

Brief Contents

B r i e f C o n t e n t s Chapter 1 The Science of Animal Behavior 2 Chapter 2 Evolution and the Study of Animal Behavior 20 Chapter 3 Methods for Studying Animal Behavior 38 Chapter 4 Behavioral Genetics 56 Chapter 5 Learning and Cognition 78 Chapter 6 Communication 112 Chapter 7 Foraging Behavior 142 Chapter 8 Antipredator Behavior 170 Chapter 9 Dispersal and Migration 196 Chapter 10 Habitat Selection, Territoriality, and Aggression 226 Chapter 11 Mating Behavior 254 Chapter 12 Mating Systems 286 Chapter 13 Parental Care 312 Chapter 14 Social Behavior 338 A p p e n d i x 1 Scientific Literature 372 Appendix 2 Writing a Scientific Paper 374 Appendix 3 Animal Care Information 377 C o n t e n t s P r e f a c e x x i i i Chapter 1 The Science of Animal Behavior 2 1.1 Animals and their behavior are an integral part of human society 4 Recognizing and defi ning behavior 5 Measuring behavior: elephant ethograms 5 1.2 Th e scientifi c method is a formalized way of knowing about the natural world 6 Th e importance of hypotheses 7 Th e scientifi c method 7 Correlation and causality 10 Hypotheses and theories 11 Social sciences and the natural sciences 11 1.3 Animal behavior scientists test hypotheses to answer research questions about behavior 12 Hypothesis testing in wolf spiders 12 Negative results and directional hypotheses 13 Generating hypoth eses 14 Hypotheses from mathematical models 14 1.4 Anthropomorphic explanations of behavior assign human emotions to animals and can be diffi cult to test 15 1.5 Scientifi c knowledge is generated and