Prosecutorial Discretion: the Decision to Charge an Annotated Bibliography LOAN DOCUMENT RETURN TO: NCJRS P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

A Federal Criminal Case Timeline

A Federal Criminal Case Timeline The following timeline is a very broad overview of the progress of a federal felony case. Many variables can change the speed or course of the case, including settlement negotiations and changes in law. This timeline, however, will hold true in the majority of federal felony cases in the Eastern District of Virginia. Initial appearance: Felony defendants are usually brought to federal court in the custody of federal agents. Usually, the charges against the defendant are in a criminal complaint. The criminal complaint is accompanied by an affidavit that summarizes the evidence against the defendant. At the defendant's first appearance, a defendant appears before a federal magistrate judge. This magistrate judge will preside over the first two or three appearances, but the case will ultimately be referred to a federal district court judge (more on district judges below). The prosecutor appearing for the government is called an "Assistant United States Attorney," or "AUSA." There are no District Attorney's or "DAs" in federal court. The public defender is often called the Assistant Federal Public Defender, or an "AFPD." When a defendant first appears before a magistrate judge, he or she is informed of certain constitutional rights, such as the right to remain silent. The defendant is then asked if her or she can afford counsel. If a defendant cannot afford to hire counsel, he or she is instructed to fill out a financial affidavit. This affidavit is then submitted to the magistrate judge, and, if the defendant qualifies, a public defender or CJA panel counsel is appointed. -

Legal Methods for the Suppression of Organized Crime (A Symposium) Arthur Buller

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 48 | Issue 4 Article 8 1958 Legal Methods for the Suppression of Organized Crime (A Symposium) Arthur Buller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Arthur Buller, Legal Methods for the Suppression of Organized Crime (A Symposium), 48 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 414 (1957-1958) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CRIMINAt LAW CASE NOTES AND COMMENTS Prepared by students of Northwestern University School of Law, under the direction of the student members of the Law School's Journal Editorial Board. Arthur Buller, Editor-in-Chief Arthur Rollin, Associate Editor Marvin Aspen Jay Oliff Malcolm Gaynor Louis Sunderland Ronald Mora Howard Sweig LEGAL METHODS FOR THE SUPPRESSION OF ORGANIZED CRIME (A SYMPOSIUM) Organized crime is a vital problem in the "The Use of Equitable Devices to Suppress field of law enforcement. Because of the nature Organized Crime", will consider the mechanics of its various forms of activity, the suppression and availability of the use of the injunction and of organized crime presents difficulties not other equitable remedies where the usual legal ordinarily encountered in other areas of criminal remedies have proved inadequate. The fifth and conduct. In this and subsequent issues of the concluding paper, "Indirect Control of Organized Journal, a series of articles will examine these Crime Through Liquor License Revocation", will problems and the legal remedies available for examine this tactic as a substitute for direct their solution. -

Brief of Amici Curiae National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and American Civil Liberties Union in Support of Respondent

No. 16-1495 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States CITY OF HAYS, KANSAS, Petitioner, v. MATTHEW JACK DWIGHT VOGT, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CRIMINAL DEFENSE LAWYERS AND AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT Barbara E. Bergman Jeffrey A. Mandell NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF Counsel of Record CRIMINAL DEFENSE LAWYERS Laura E. Callan 1660 L Street, N.W. Erika L. Bierma Washington, D.C. 20036 Eileen M. Kelley Elizabeth C. Stephens David D. Cole STAFFORD ROSENBAUM LLP Rachel Wainer Apter 222 W. Washington Ave., Ezekiel Edwards Suite 900 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES Madison, WI 53701 UNION FOUNDATION (608) 256-0226 915 15th Street N.W. [email protected] Washington, D.C. 20005 December 20, 2017 Counsel for Amici Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS Page STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .......................................................... 1 STATEMENT .............................................................. 3 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 9 THE FIFTH AMENDMENT’S GUARANTEE AGAINST SELF- INCRIMINATION APPLIES AT PRELIMINARY HEARINGS. ............................ 11 A. This principle is consistent with the Constitution’s text and with precedent……… ............................................. 11 B. Limiting the Self-Incrimination Clause’s application to the criminal trial itself would severely prejudice defendants…….. ............................................ 18 C. The government’s policy concerns do not withstand scrutiny. ............................ 24 CONCLUSION .......................................................... 29 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Best v. City of Portland, 554 F.3d 698 (7th Cir. 2009) ............................ 14, 24 Blyew v. United States, 13 Wall. 581 (1872) ................................................ 13 Chavez v. Martinez, 538 U.S. 760 (2003) .......................................... 13, 27 Coleman v. Alabama, 399 U.S. -

Felony Case Processing Study Phase I Final Report and Recommendations

Cuyahoga County, Ohio Felony Case Processing Study Phase I Final Report and Recommendations Submitted to: The Cuyahoga County Commissioners and The Cuyahoga County Adult Justice Group By The Justice Management Institute May 22, 2005 Contact Person Douglas K. Somerlot 1900 Grant Street, Suite 630 Denver, Colorado 80203 (303) 831-7564 Fax: (303) 831-4564 Table of Contents Item Page Number Summary of Recommendations 1 Impact of Recommendations on Staff and Computer Equipment 8 Background 14 New Proposals and Developments 25 Issues and Recommendations 29 Appendix 1, Description of The Justice Management Institute 63 Appendix 2, Description of The Adult Justice Group 66 Appendix 3, Methodology and Individuals Interviewed 68 i THE JUSTICE MANAGEMENT INSTITUTE Cuyahoga County, Ohio Felony Case Processing Study– Phase I Summary of Recommendations I. GOVERNANCE OF THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM. Criminal Justice Supervisory Committee. Recommendation Number 1: Cuyahoga County should form a county-wide Criminal Justice Supervisory Committee. The Committee should be drawn from key leaders at the county and municipal levels and should have top quality staff. It should be charged with planning for system-wide improvements in criminal justice system operations, monitoring progress toward achievement of goals, acting collectively to address systemic problems, and reporting at least annually to county and municipal governing bodies. II. ARREST TO ARRAIGNMENT. A. Case investigation processing paths should be consistent with the severity and complexity of the crime charged and the possible sentence that could be imposed. Recommendation Number 2: A committee composed of representatives of the police agencies, municipal and county prosecutor’s office, public defender, and probation department should develop a case investigation process which accelerates the law enforcement processing of cases where the charges are lower grade felonies, cases where there is no victim and few witnesses, and cases involving low-level substance abuse. -

A Plea for Discovery of Evidence in Aggravation

Death by Ambush: A Plea for Discovery of Evidence in Aggravation Tamara L. Graham* I. Introduction On February 26, 1997, the Commonwealth of Virginia executed Coleman Wayne Gray for the capital murder of Richard McClelland, the manager of Murphy’s Mart in Portsmouth, Virginia.1 One might argue, however, that he was actually executed for the murders of Lisa and Shanta Sorrell, despite having never been charged with those crimes.2 The Sorrell murders looked somewhat like McClelland’s murder; however, the only direct link that the Commonwealth had between Gray and the Sorrell murders was the testimony of Melvin Tucker, Gray’s accomplice in the McClelland murder.3 Tucker received a life sentence in exchange for, among other things, his testimony that Gray told him that he had killed the Sorrells.4 To convince the jury that Gray would “constitute a continuing serious threat to society,” the Commonwealth introduced testimony from the detective and the medical examiner in the Sorrell case and, in effect, conducted a mini-murder trial within the sentencing phase of the trial of the only crime for which it had actually indicted Gray.5 Gray’s counsel asked the trial court to exclude the surprise evidence.6 The court refused, and the jury * J.D. Candidate, May 2006, Washington and Lee University School of Law; B.A., Hanover College, 1996. I thank professor David I. Bruck for his guidance and wisdom; Jessie Seiden, Meghan Morgan, Max Smith, and Todd Egland for their editorial prowess; Marsha L. Dutton for providing the stylistic foundation for everything I write; my 2006 VC3 colleagues for having my back; and Carrie Herring for her patience and support. -

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

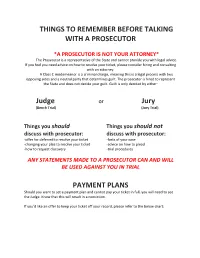

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

Jun a 1 Ioqy Marcia J

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO STATE OF OHIO, Case No. 2007-0923 Plaintiff-Appellee, On Appeal from the Licking County Court of Appeals, V. Fifth Appellate District HAROLD T. BIESER, Court of Appeals Case No. 06 CA 00045 Defendant-Appellant. MEMORANDUM OF DEFENDANT-APPELLANT HAROLD T. BIESER IN SUPPORT OF JURISDICTION Tricia M. Klockner (0077414) John J. Kulewicz (0008376) Assistant Law Director (Counsel of Record) City of Newark Alexandra T. Schimmer (0075732) 40 West Main Street Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP Newark, Ohio 43055 52 East Gay Street (740) 349-6663 P.O. Box 1008 Columbus, Ohio 43216-1008 Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellee (614) 464-5634 State of Ohio (614) 719-4812 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant Harold T. Bieser JUN A 1 IOQY MARCIA J. MENGEL; CLERK SUPREME COURT OF OHIO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. THIS CASE INVOLVES A SUBSTANTIAL CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION AND RAISES QUESTIONS OF PUBLIC OR GREAT GENERAL INTEREST .............1 II. STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND FACTS . ...................................................................4 III. ARGUMENT IN SUPPORT OF PROPOSITIONS OF LAW ...........................................7 PROPOSITION OF LAW NO. 1: The rule announced in State v. Broughton (1991), 62 Ohio St.3d 253, 581 N.E. 2d 541 -- that speedy-trial time ordinarily stops running in the interim between a nolle prosequi dismissal and refiling of the same charges -- does not apply where the defendant was not notified of the dismissal and the bond was retained after dismissal ...........................................................7 PROPOSITION OF LAW NO. 2: The State violates the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution, as well as Section 10, Article I, of the Ohio Constitution and the Ohio Speedy Trial Act (R.C. -

SELECTED DECISIONS of the HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE Under the OPTIONAL PROTOCOL

OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS SELECTED DECISIONS OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE under THE OPTIONAL PROTOCOL Volume 7 Sixty-sixth to seventy-fourth sessions (July 1999 – March 2002) UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2006 NOTE Material contained in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given and a copy of the publication containing the reprinted material is sent to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Palais des Nations, 8-14 avenue de la Paix, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. CCPR/C/OP/7 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.06.XIV.1 ISBN 92-1-130294-3 ii CONTENTS (Selected decisions — Sixty-sixth to seventy-fourth sessions) Page Introduction........................................................................................................................... 1 FINAL DECISIONS A. Decision declaring a communication admissible (the number of the Committee session is indicated in brackets) No. 845/1999 [67] Rawle Kennedy v. Trinidad and Tobago............................. 5 B. Decisions declaring a communication inadmissible (the number of the Committee session is indicated in brackets) No. 717/1996 [66] Acuña Inostroza et al v. Chile.............................................. 13 No. 880/1999 [74] Terry Irving v. Australia...................................................... 18 No. 925/2000 [73] Wan Kuok Koi v. Portugal .................................................. 22 C. Views under article 5 (4) of the Optional Protocol No. 580/1994 [74] Glen Ashby v. Trinidad and Tobago ................................... 29 No. 688/1996 [69] María Sybila Arredondo v. Peru.......................................... 36 No. 701/1996 [69] Cesario Gómez Vázquez v. Spain........................................ 43 No. 727/1996 [71] Dobroslav Paraga v. Croatia ................................................ 48 No. 736/1997 [70] Malcolm Ross v. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

Criminal Prosecution Guide

CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE JOB GUIDE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Description Types of Employers Prosecutors work in all levels of government–local, state, Federal—U.S. Department of Justice: and federal. Prosecutors are responsible for representing the government in criminal cases, including Post-Graduate Jobs. The DOJ hires entry-level attorneys felonies and misdemeanors. At the state and local level, only through the Attorney General’s Honors Program. this work is typically done by District Attorneys’ Offices The application period is very short, typically the month or Solicitors’ Offices. Offices of State Attorneys General of August in the year prior to your graduation year. The may also have some responsibility for criminal matters of number of attorneys hired varies from year to year, and statewide significance or for criminal appellate or post- the positions are highly competitive. conviction matters. Federal criminal matters (e.g., financial crimes, drug enforcement, and organized Paid Summer Internships. The DOJ hires a number of crime) are typically handled by a U.S. Attorney’s Office students for paid summer positions through its Summer (USAO) either exclusively or in cooperation with the Law Intern Program. These positions are open to 1Ls Criminal Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney and 2Ls, although most successful applicants intern General. during their 2L summer. Graduating law students who will enter a judicial clerkship or a full-time graduate program may intern following graduation. The application Qualifications period is very short, typically the month of August in the year prior to the summer you would be working. Many prosecutors’ offices prefer that entry-level attorneys have coursework, summer experience and/or Unpaid Internships.