An Economic Analysis of the Guaranty Contract Avery Wiener Katzt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wolfsberg Group Trade Finance Principles 2019

Trade Finance Principles 1 The Wolfsberg Group, ICC and BAFT Trade Finance Principles 2019 amendment PUBLIC Trade Finance Principles 2 Copyright © 2019, Wolfsberg Group, International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and BAFT Wolfsberg Group, ICC and BAFT hold all copyright and other intellectual property rights in this collective work and encourage its reproduction and dissemination subject to the following: Wolfsberg Group, ICC and BAFT must be cited as the source and copyright holder mentioning the title of the document and the publication year if available. Express written permission must be obtained for any modification, adaptation or translation, for any commercial use and for use in any manner that implies that another organization or person is the source of, or is associated with, the work. The work may not be reproduced or made available on websites except through a link to the relevant Wolfsberg Group, ICC and/or BAFT web page (not to the document itself). Permission can be requested from the Wolfsberg Group, ICC or BAFT. This document was prepared for general information purposes only, does not purport to be comprehensive and is not intended as legal advice. The opinions expressed are subject to change without notice and any reliance upon information contained in the document is solely and exclusively at your own risk. The publishing organisations and the contributors are not engaged in rendering legal or other expert professional services for which outside competent professionals should be sought. PUBLIC Trade Finance Principles -

SAMPLE NOTES from OUR LLB CORE GUIDE: Contract Law Privity Chapter

SAMPLE NOTES FROM OUR LLB CORE GUIDE: Contract Law Privity chapter LLB Answered is a comprehensive, first-class set of exam-focused study notes for the Undergraduate Law Degree. This is a sample from one of our Core Guides. We also offer dedicated Case Books. Please visit lawanswered.com if you wish to purchase a copy. Notes for the LPC are also available via lawanswered.com. This chapter is provided by way of sample, for marketing purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice. No warranties as to its contents are provided. All rights reserved. Copyright © Answered Ltd. PRIVITY KEY CONCEPTS 5 DOCTRINE OF PRIVITY Under the common law: A third party cannot… enforce , be liable for, or acquire rights under … a contract to which he is not a party. AVOIDING THE DOCTRINE OF PRIVITY The main common law exceptions are: AGENCY RELATIONSHIPS ASSIGNMENT TRUSTS JUDICIAL INTERVENTION The main statutory exception is: CONTRACTS (RIGHTS OF THIRD PARTIES) ACT 1999 44 PRIVITY WHAT IS PRIVITY? “The doctrine of privity means that a contract cannot, as a general rule, confer PRIVITY rights or impose obligations arising under it on any person except the parties to it.” Treitel, The Law of Contract. Under the doctrine of privity: ACQUIRE RIGHTS UNDER A third party cannot BE LIABLE FOR a contract to which he is not a party. ENFORCE NOTE: the doctrine is closely connected to the principle that consideration must move from the promisee (see Consideration chapter). The leading cases on the classic doctrine are Price v Easton, Tweddle v Atkinson and Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v Selfridges & Co Ltd. -

Legal Position Agreement with Personal Guarantee at Bank Medan Branch

Legal Position Agreement with Personal Guarantee at Bank Medan Branch Vincent Leonardo Tantowie, Willy Tanjaya, and Herman Brahmana, Elvira Fitriyani Pakpahan Magister of Notary, Universitas Prima Indonesia, Jl. Sekip Simpang Sikambing, Medan, Indonesia Keywords: Legal Agreement, Guarantee and Personal Guarantee. Abstract: In providing credit facilities, all banks always refer to the Loan to Value of the credit value. The value of the collateral provided is in the form of material guarantees, whether installed on a KPR, KPR, Fiduciary basis or Pawn and Cessie. If there is a lack of guarantee value that is relaxed by the internal and external assessment team, the Bank always asks for additional guarantees in the form of personal guarantees (personal guarantees) or company guarantees (company guarantees). This must be watched out for by bankers or legal officers of a finance company where if a company or individual has provided personal guarantees for a debt from a certain debtor, then it must be given strict provisions, that the guarantor must also be accompanied by a material guarantee. 1 INTRODUCTION this note, attention is paid to the importance of structuring the details of claims and the Banks as a company engaged in finance, all banking consequences for which employee claims are activities are always related to the financial sector, formulated incorrectly. Possible solutions available so talking about banks is inseparable from financial to employees in terms of both general law and problems. Banking activities that are the first to raise statutory are investigated (Barnard, 2010). If we funds from the wider community known as banking look deeper into the business activities of banks, in activities are funding activities. -

Contract of Guarantee for Non-Shareholder Loans Between

CONTRACT NO. <00000> FORM For information purposes Contract of Guarantee for Non-Shareholder Loans Non-Honoring of a Sovereign Financial Obligation between the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency and [Guarantee Holder] This draft document is subject to MIGA’s approval and as such cannot be considered a contract or an offer to enter into a contract. Only the document executed by MIGA, as approved by MIGA’s senior management and the Guarantee Holder, will contain the terms and conditions that shall bind them. Until this document is executed by MIGA and the Guarantee Holder, neither MIGA nor the Guarantee Holder intends to be bound by its terms and conditions. The terms and conditions of this draft document are distributed to the Guarantee Holder on a confidential basis. [2016 FORMS – OCTOBER 2016] CONTRACT OF GUARANTEE FOR NHSFO CONTRACT NO. <00000> Contract of Guarantee for Non-Shareholder Loans Non-Honoring of a Sovereign Financial Obligation Table of Contents Part I – Special Conditions .............................................................................................................. 1 Part II – General Conditions ............................................................................................................ 5 Article 1. Application and Interpretation .................................................................................... 5 Article 2. Definitions .................................................................................................................. 5 Article 3. Non-Honoring of a Sovereign -

Federal Tort Claims Act II

Federal Tort Claims Act II In This Issue Using the “Private Individual Under Like Circumstances” to Your Advantage: The Analogous Private Liability Requirement Under the January Federal Tort Claims Act . 1 2011 By Adam M. Dinnell Volume 59 Number 1 The Federal Tort Claims Act is a Very Limited Waiver of Sovereign United States Immunity – So Long as Agencies Follow Their Own Rules and Do Not Department of Justice Executive Office for Simply Ignore Problems . 16 United States Attorneys Washington, DC By David S. Fishback 20530 H. Marshall Jarrett Director Jurisdiction Limits on Damages in FTCA Cases . 31 By Jeff Ehrlich Contributors' opinions and statements should not be considered an endorsement by EOUSA for any policy, program, The Benefit of Proving Benefits – Avoiding Paying Twice For the Same or service. Injury Under the FTCA . .35 The United States Attorneys' Bulletin is published pursuant to 28 By Conor Kells CFR § 0.22(b). The United States Attorneys' Defending Wrongful Death and Survival Claims Brought Under the Bulletin is published bimonthly by the Executive Office for United Federal Tort Claims Act . 41 States Attorneys, Office of Legal Education, 1620 Pendleton Street, By Jamie L. Hoxie Columbia, South Carolina 29201. Managing Editor The United States’ Waivers of Sovereign Immunity in Admiralty . .46 Jim Donovan By Peter Myer Law Clerks Elizabeth Gailey Carmel Matin Researching the Legislative History of the Federal Tort Claims Act . .52 Internet Address By Jennifer L. McMahan and Mimi Vollstedt www.usdoj.gov/usao/ reading_room/foiamanuals. html Send article submissions and address changes to Managing Editor, United States Attorneys' Bulletin, National Advocacy Center, Office of Legal Education, 1620 Pendleton Street, Columbia, SC 29201. -

The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs

TH AL LAW JORAL JOHN C.P. GOLDBERG The Constitutional Status of Tort Law: Due Process and the Right to a Law for the Redress of Wrongs A B ST RACT. In our legal system, redressing private wrongs has tended to be the business of tort law, itself traditionally a branch of the common law. But do individuals have a "vested interest" in law that redresses wrongs? If so, do state and federal governments have a constitutional duty to provide that law? Since the New Deal era, conventional wisdom has held that individuals do not possess such a right, and consequently, government bears no such duty. In this view, it is a matter of unfettered legislative discretion- "whim" -whether or how to provide a law of redress. This view is wrongheaded. To be clear: I do not argue that individuals have a property-like interest in a particular corpus of tort rules. The law of tort is always capable of improvement, and legislatures have an obligation and the requisite authority to undertake such improvements. Nonetheless, I do argue that tort law, understood as a law for the redress of private wrongs, forms part of the basic structure of our government. And though the Constitution does not confer on any particular individual a right to a specific version of tort rules, all American citizens have a right to a body of law for the redress of private wrongs that generates meaningful and judicially enforceable limits on tort reform legislation. A UT HO R. John C.P. Goldberg is Associate Dean for Research and Professor, Vanderbilt Law School. -

Permitting Recovery for Pre-Impact Emotional Distress Kathleen M

Boston College Law Review Volume 28 Article 2 Issue 5 Number 5 9-1-1987 When Circumstances Provide a Guarantee of Genuineness: Permitting Recovery for Pre-Impact Emotional Distress Kathleen M. Turezyn Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Kathleen M. Turezyn, When Circumstances Provide a Guarantee of Genuineness: Permitting Recovery for Pre-Impact Emotional Distress, 28 B.C.L. Rev. 881 (1987), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol28/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN CIRCUMSTANCES PROVIDE A GUARANTEE OF GENUINENESS: PERMITTING RECOVERY FOR PRE-IMPACT EMOTIONAL DISTRESSt Kathleen M. Turezyn* I. INTRODUCTION "Uh-Oh"' That fateful phrase was uttered by pilot Michael J. Smith at almost the same instant that the space shuttle "Challenger" exploded before the eyes of the unsuspecting NASA ground control crew, the families and friends of the astronauts invited to watch the launch, and television viewers who had just witnessed another apparently successful space launch. It was the last communication by a member of the crew, 2 and suggests that at least one of the astronauts was aware of an impending disaster.' Evidence produced by an investigation of the explosion appears to support the conclusion that the crew survived the explosion in space only to find themselves trapped in the crew module as it fell toward earth and its ultimate destination deep in the Atlantic Ocean. -

Personal Guarantee of Rental Agreement

Guarantee of Rental/Lease Agreement 1. In consideration of the execution of the Rental/Lease Agreement by and between Campos Rental Properties (Owner/Agent) and ______________________________ (Tenant) for the property known as ______________________________ and for valuable consideration, receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, the undersigned _______________________________, herein referred to as Guarantor, does hereby guarantee unconditionally to Owner/Agent, and or including Owner’s/Agent’s successor and assigns, the prompt payment by Tenant of the rent or any other sums which become due pursuant to the Rental/Lease Agreement, including any and all courts costs or attorney’s fees incurred in enforcing the Rental/Lease Agreement. 2. In the event of the breach of any terms of the Rental/Lease Agreement by Tenant, Guarantor shall be liable for any damages, financial or physical, caused by Tenant, including any and all legal fees incurred in enforcing the Rental/Lease Agreement. 3. This Guarantee may be immediately enforced by Owner/Agent upon any default by Tenant and an action against Guarantor may be brought at any time without first seeking recourse against Tenant. 4. The insolvency of Tenant or nonpayment of any sums due from Tenant may be deemed a default giving rise to action by Owner/Agent against Guarantor. 5. If any legal actions or other proceedings are brought by any party to enforce any part of this Guarantee, the prevailing party shall be entitled to reasonable attorney’s fees and costs incurred. 6. This Guarantee does not confer a right to possession of the premises by Guarantor, and Owner/Agent is not required to serve Guarantor with any notices to terminate or to perform covenants, including any demand for payment of rent, prior to Owner/Agent proceeding against Guarantor for Guarantor’s obligations under this guarantee. -

Guarantor Liability 101

Guarantor Liability 101 2020 Edition LawPracticeCLE Unlimited All Courses. All Formats. All Year. ABOUT US LawPracticeCLE is a national continuing legal education company designed to provide education on current, trending issues in the legal world to judges, attorneys, paralegals, and other interested business professionals. New to the playing eld, LawPracticeCLE is a major contender with its oerings of Live Webinars, On-Demand Videos, and In-per- son Seminars. LawPracticeCLE believes in quality education, exceptional customer service, long-lasting relationships, and networking beyond the classroom. We cater to the needs of three divisions within the legal realm: pre-law and law students, paralegals and other support sta, and attorneys. WHY WORK WITH US? At LawPracticeCLE, we partner with experienced attorneys and legal professionals from all over the country to bring hot topics and current content that are relevant in legal practice. We are always looking to welcome dynamic and accomplished lawyers to share their knowledge! As a LawPracticeCLE speaker, you receive a variety of benets. In addition to CLE teaching credit attorneys earn for presenting, our presenters also receive complimentary tuition on LawPracticeCLE’s entire library of webinars and self-study courses. LawPracticeCLE also aords expert professors unparalleled exposure on a national stage in addition to being featured in our Speakers catalog with your name, headshot, biography, and link back to your personal website. Many of our courses accrue thousands of views, giving our speakers the chance to network with attorneys across the country. We also oer a host of ways for our team of speakers to promote their programs, including highlight clips, emails, and much more! If you are interested in teaching for LawPracticeCLE, we want to hear from you! Please email our Directior of Operations at [email protected] with your information. -

Surety Bonds: a Watertight Guarantee?

RISK FINANCING > In partnership with: from delays in projects or damage to equipment. Insurance is a two-party contract between the insured Surety bonds: a and the insurance company. As with insurance, there are several varieties of bonds. Below, Atradius Bonding director Pietro watertight guarantee? Lanzillotta helps us uncover the benefits of surety bonds by answering readers’ frequently asked questions. WHAT BONDS DO I NEED TO CONSIDER? There are number of bonds, including: ● Bid bonds: If you are a construction contractor and Given the complexity and cost involved in large-scale want to participate in a government project to build or refurbish a bridge, for example, you will first need infrastructure projects, surety bonds promise a new level of a bid bond in order to enter the tender process. A bid bond insures the original bid, guaranteeing the protection for all parties involved. Atradius Bonding director project owner that you are able to enter the contract at the bid price stated and to provide the required THE BENEFITS OF BONDS Pietro Lanzillotta guides us through the benefits performance and payment bonds if you are awarded the contract. Bonds are a valuable alternative to bank guarantees and ● Performance bonds: Upon winning the tender, cash retention, as well as an effective way to increase urope’s construction industry may not In each of these areas will be significant risks – you need a performance bond to secure the your capital base. attract the same level of attention as labour difficulties, material shortages, equipment contractual obligations of your performance as it China or the Gulf Co-operation Council, problems, contract breaches, failures from service relates to agreed conditions – for example, price, but the sector is made up of mega providers – all of which could bring projects to a timeline and quality. -

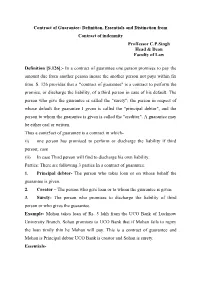

Contract of Guarantee: Definition, Essentials and Distinction from Contract of Indemnity Proffessor C.P.Singh Head & Dean Faculty of Law

Contract of Guarantee: Definition, Essentials and Distinction from Contract of indemnity Proffessor C.P.Singh Head & Dean Faculty of Law Definition [S.126]:- In a contract of guarantee one person promises to pay the amount due from another person incase the another person not pays within fix time. S. 126 provides that a "contract of guarantee" is a contract to perform the promise, or discharge the liability, of a third person in case of his default. The person who give the guarantee is called the "surety"; the person in respect of whose default the guarantee I given is called the "principal debtor", and the person to whom the guarantee is given is called the "creditor". A guarantee may be either oral or written. Thus a contr5act of guarantee is a contract in which- (i) one person has promised to perform or discharge the liability if third person; case (ii) In case Third person will find to discharge his own liability. Parties: There are following 3 parties In a contract of guarantee. 1. Principal debtor- The person who takes loan or on whose behalf the guarantee is given. 2. Creator – The person who give loan or to whom the guarantee is given. 3. Surely- The person who promises to discharge the liability of third person or who gives the guarantee. Example- Mohan takes loan of Rs. 5 lakh from the UCO Bank of Lucknow University Branch. Sohan promises to UCO Bank that if Mohan fails to rupey the loan timily thin he Mohan will pay. This is a contract of guarantee and Mohan is Principal debtor UCO Bank is creator and Sohan is surety. -

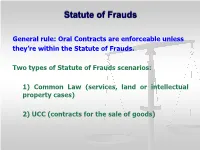

Statute of Frauds

Statute of Frauds General rule: Oral Contracts are enforceable unless they’re within the Statute of Frauds. Two types of Statute of Frauds scenarios: 1) Common Law (services, land or intellectual property cases) 2) UCC (contracts for the sale of goods) What is within the Statute of Frauds? Common Law Statute of Frauds cases: 1. Contract to guarantee the debt of another 2. Contract to pay the debts of a decedent from one’s own funds 3. Contract that is incapable of being performed within one year from the time of the agreement. Contrast: Employment contract for 5 years: Within the SOF Lifetime employment contract: NOT within the SOF 4. Promises in consideration of marriage 5. Contracts for the transfer of an interest in real estate for more than one year U.C.C. Statute of Frauds 6. Contracts for the sale of goods for $500 or more Quiz Time! The Statute of Frauds - Satisfaction by Writing There must be a writing that is signed by the party against whom the contract is being enforced. What must the writing contain? In common law cases, all material terms. In UCC cases, only the existence of an agreement and quantity is needed. The Statute of Frauds - Satisfaction by Performance Full performance is enough to satisfy the SOF. Part Performance: Never sufficient in a services contract case. Part Performance in a Real Estate Contract requires: Possession + either payment or improvements to the real estate. UCC Cases: Part performance (receiving and accepting the goods) makes the contract enforceable, but only to the extent of the part performance The creation of unique goods that cannot easily be re-sold to another buyer can satisfy the SOF.