Preserving the Digital Output of Independent Punk and Metal Labels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

Cassettes an Affordable Analog Companion to Vinyl BANDCAMP OPTIMIZATIONS RECORDING

FREE FOR MUSICIANS details inside GETTING THINGS DONE IN HEAVY UNDERGROUND MUSIC • AUGUST 2020 Cassettes An affordable analog companion to vinyl BANDCAMP OPTIMIZATIONS RECORDING .................. APART 9 Improve your store forever in an hour Advice for collaborating on sessions when you can’t be in the same room Interviews with: CHRISTINE KELLY DOOMSTRESS ALEXIS HOLLADA Owner of Tridroid Records Singer, songwriter, bassist, band leader EARSPLIT PR DAN KLEIN New York veterans delivering Producer at Iron Hand Audio, exposure to the masses drummer for FIN, Berator & more DAVID PAUL SEYMOUR VITO MARCHESE Illustrator of doom Novembers Doom, The Kahless Clone, Resistance HQ Publishing VOL. 1, ISSUE 1. THERE WILL BE TYPOS, WE GUARANTEE IT. 4 Vito Marchese 8 Earsplit PR Free print subscriptions 12 Cassettes for US musicians. 18 Doomstress Alexis Hollada Subscribe online at 22 Dan Klein WorkhorseMag.com (or just email us) 27 Christine Kelly 30 David Paul Seymour 34 Bandcamp Optimizations Workhorse Magazine Harvester Publishing LLC, 37 Recording.............apart www.workhorsemag.com PO Box 322, Hutto TX 78634 [email protected] 38 Publisher Notes [email protected] Cover art by David Paul Seymour The tiny, USA made condenser microphone, making a big sound on countless hits. "I think the first thing I threw it on was my guitar amp and I remember being blown away, honestly. The sound was so big and the sonic spectrum felt so broad and open, yet focused." - Teppei Teranishi (Thrice) L I T T L E B L O N D I E M I C R O P H O N E S Exclusive offer! Save 15% with coupon code: Workhorse Buy now on LittleBlondie.com Photo by Hillarie Jason, taken at Prophecy Fest 2018 Vito Marchese Chicago guitarist on his work with Novembers Doom, The Kahless Clone and his tablature publishing company, Resistance HQ Publishing. -

Mysticism, Implicit Religion and Gravetemple's Drone Metal By

1 The Invocation at Tilburg: Mysticism, Implicit Religion and Gravetemple’s Drone Metal by Owen Coggins 1.1 On 18th April 2013, an extremely slow, loud and noisy “drone metal” band Gravetemple perform at the Roadburn heavy metal and psychedelic rock festival in Tilburg in the Netherlands. After forty-five minutes of gradually intensifying, largely improvised droning noise, the band reach the end of their set. Guitarist Stephen O’Malley conjures distorted chords, controlled by a bank of effects pedals; vocalist Attila Csihar, famous for his time as singer for notorious and controversial black metal band Mayhem, ritualistically intones invented syllables that echo monastic chants; experimental musician Oren Ambarchi extracts strange sounds from his own looped guitar before moving to a drumkit to propel a scattered, urgent rhythm. Momentum overtaking him, a drumstick slips from Ambarchi’s hand, he breaks free of the drum kit, grabs for a beater, turns, and smashes the gong at the centre of the stage. For two long seconds the all-encompassing rumble that has amassed throughout the performance drones on with a kind of relentless inertia, still without a sonic acknowledgement of the visual climax. Finally, the pulsating wave from the heavily amplified gong reverberates through the corporate body of the audience, felt in physical vibration more than heard as sound. The musicians leave the stage, their abandoned instruments still expelling squalling sounds which gradually begin to dissipate. Listeners breathe out, perhaps open their eyes, raise their heads, shift their feet and awaken enough to clap and shout appreciation, before turning to friends or strangers, reaching for phrases and gestures, often in a vocabulary of ritual, mysticism and transcendence, which might become touchstones for recollection and communication of their individual and shared experience. -

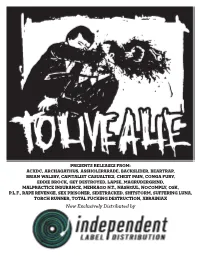

Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW!

PRESENTS RELEASES FROM: ACXDC, ARCHAGATHUS, ASSHOLEPARADE, BACKSLIDER, BEARTRAP, BRIAN WALSBY, CAPITALIST CASUALTIES, CHEST PAIN, CONGA FURY, EDDIE BROCK, GET DESTROYED, LAPSE, MAGRUDERGRIND, MALPRACTICE INSURANCE, MEHKAGO N.T., NASHGUL, NOCOMPLY, OSK, P.L.F., RAPE REVENGE, SEX PRISONER, SIDETRACKED, SHITSTORM, SUFFERING LUNA, TORCH RUNNER, TOTAL FUCKING DESTRUCTION, XBRAINIAX Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Los Angeles, CA Key Markets: LA & CA, Texas, Arizona, DC, Baltimore MD, New York, Canada, Germany For Fans of: MAGRUDERGRIND, NASUM, NAPALM DEATH, DESPISE YOU ANTI-CHRIST DEMON CORE’s He Had it Coming repress features the original six song EP released in 2005 plus two tracks from the same session off the A Sign Of Impending Doom Compilation. The band formed in 2003, recorded these songs in 2005 and then vanished for awhile on a many- year hiatus, only to resurface and record and release a brilliant new EP and begin touring again in 2011/2012. The original EP is long sought after ARTIST: ACXDC by grindcore and powerviolence fiends around the country and this is your TITLE: He Had It Coming chance to grab the limited repress. LABEL: TO LIVE A LIE CAT#: TLAL64AB Marketing Points: FORMAT: 7˝ GENRE: Grindcore • Hugely Popular Band BOX LOT: NA • Repress of Long Sold Out EP SRLP: $5.48 • Huge Seller UPC: 616983334836 • Two Extra Songs In Additional To Originals EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS • Two Bonus Songs Never Before Pressed To Vinyl, In Additional To Originals Tracklist: 1. Dumb N Dumbshit 2. Death Spare Not The Tiger 3. Anti-Christ Demon Core 4. -

15 / Maijs 16 / Maijs 22 / Maijs 23 / Maijs

ЛEС ЗВУКОВ / KLANGWALD / LA FÔRET DES SONS / SOUND FOREST / LYDSKOG / ÄÄNIMETSÄ / HLJÓÐ SKÓGUR 15.MAIJS, RĪGAS MĀKSLAS TELPA 22.MAIJS, ANGLIKĀŅU BAZNĪCA 23.MAIJS, ANGLIKĀŅU BAZNĪCA SADARBĪBĀ AR SPIRE / TOUCH MUSIC Platons Buravickis (20) ir viens no Latvijas elektroniskās mūzikas jaunajiem talantiem. 1998.gadā viņš sāka apgūt kompozīciju pie Viļņa Šmīdberga, pēc Sunn O))), kas ar 22.maija koncertu aizsāks īsu Eiropas tūri, ir amerikāņu kulta grupa, kura ar savu mistisko, minimālistisko un unikālo metāla mūzikas 23.maija koncerta sadarbības partneri, leģendāro britu eksperimentālās mūzikas izdevniecību Touch Music, 1981.gadā dibināja dizaineris Džons tam pie Pētera Vaska. Trīskārtējs Latvijas Mūzikas skolu jaunrades valsts konkursa laureāts. Pētera Vaska un Borisa Avrameca iedvesmots, iepazina elektroni- interpretāciju ir šajā žanrā īstenojusi (burtiski) lēnu revolūciju. Iespējams pilnīgi pamatoti saka, ka Sunn O))) piederot lēnākā un zemākā skaņa pasaulē. Viņu Vozenkrofts ar mūzikas izdevēja Maika Hārdinga palīdzību. Tā ir kalpojusi par radošu “tramplīnu” tādiem māksliniekiem kā New Order, Cabaret Voltaire, Džā sko mūziku. 2007.gadā sāka strādāt Betona rūpnīcā un tajā laikā arī apmeklēja kompozīcijas meistarklases Berlīnē pie profesora Dītera Maka, sāka spēlēt nosaukums aizgūts no vecajiem Sunn O))) ģitāras pastiprinātājiem. Jāpiebilst, ka vēloties panākt autentisku skanējumu, grupa priekš sava koncerta uz Rīgu Voublam, Robertam Vaietam, Einstürzende Neubauten un Current 93. Izdevniecība publicēja arī Eitnes Ni Bhraonainas pirmos ierakstus. Vēlāk viņa kļuva progroka grupā Olive Messa un sakrāja lielu industriālo skaņu kolekciju, ko izmanto savos elektroakustiskajos darbos. speciāli ved šos pastiprinātājus. Jābilst, ka koncerts, ar kuru viņi atzīmē savai desmitajai jubilejai veltītā albuma Monoliths & Dimensions izdošanu, ir Baltijā pazīstama kā īru popzvaigzne Enja. Platons Buravickis (20) is one of the young talents in Latvia’s electronic music. -

17-06-27 Full Stock List Drone

DRONE RECORDS FULL STOCK LIST - JUNE 2017 (FALLEN) BLACK DEER Requiem (CD-EP, 2008, Latitudes GMT 0:15, €10.5) *AR (RICHARD SKELTON & AUTUMN RICHARDSON) Wolf Notes (LP, 2011, Type Records TYPE093V, €16.5) 1000SCHOEN Yoshiwara (do-CD, 2011, Nitkie label patch seven, €17) Amish Glamour (do-CD, 2012, Nitkie Records Patch ten, €17) 1000SCHOEN / AB INTRA Untitled (do-CD, 2014, Zoharum ZOHAR 070-2, €15.5) 15 DEGREES BELOW ZERO Under a Morphine Sky (CD, 2007, Force of Nature FON07, €8) Between Checks and Artillery. Between Work and Image (10inch, 2007, Angle Records A.R.10.03, €10) Morphine Dawn (maxi-CD, 2004, Crunch Pod CRUNCH 32, €7) 21 GRAMMS Water-Membrane (CD, 2012, Greytone grey009, €12) 23 SKIDOO Seven Songs (do-LP, 2012, LTM Publishing LTMLP 2528, €29.5) 2:13 PM Anus Dei (CD, 2012, 213Records 213cd07, €10) 2KILOS & MORE 9,21 (mCD-R, 2006, Taalem alm 37, €5) 8floors lower (CD, 2007, Jeans Records 04, €13) 3/4HADBEENELIMINATED Theology (CD, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 148, €19.5) Oblivion (CD, 2010, Die Schachtel DSZeit11, €14) Speak to me (LP, 2016, Black Truffle BT023, €17.5) 300 BASSES Sei Ritornelli (CD, 2012, Potlatch P212, €15) 400 LONELY THINGS same (LP, 2003, Bronsonunlimited BRO 000 LP, €12) 5IVE Hesperus (CD, 2008, Tortuga TR-037, €16) 5UU'S Crisis in Clay (CD, 1997, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu2, €14) Hunger's Teeth (CD, 1994, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu1, €14) 7JK (SIEBEN & JOB KARMA) Anthems Flesh (CD, 2012, Redroom Records REDROOM 010 CD , €13) 87 CENTRAL Formation (CD, 2003, Staalplaat STCD 187, €8) @C 0° - 100° (CD, 2010, Monochrome -

Counting the Music Industry: the Gender Gap

October 2019 Counting the Music Industry: The Gender Gap A study of gender inequality in the UK Music Industry A report by Vick Bain Design: Andrew Laming Pictures: Paul Williams, Alamy and Shutterstock Hu An Contents Biography: Vick Bain Contents Executive Summary 2 Background Inequalities 4 Finding the Data 8 Key findings A Henley Business School MBA graduate, Vick Bain has exten sive experience as a CEO in the Phase 1 Publishers & Writers 10 music industry; leading the British Academy of Songwrit ers, Composers & Authors Phase 2 Labels & Artists 12 (BASCA), the professional as sociation for the UK's music creators, and the home of the Phase 3 Education & Talent Pipeline 15 prestigious Ivor Novello Awards, for six years. Phase 4 Industry Workforce 22 Having worked in the cre ative industries for over two decades, Vick has sat on the Phase 5 The Barriers 24 UK Music board, the UK Music Research Group, the UK Music Rights Committee, the UK Conclusion & Recommendations 36 Music Diversity Taskforce, the JAMES (Joint Audio Media in Education) council, the British Appendix 40 Copyright Council, the PRS Creator Voice program and as a trustee of the BASCA Trust. References 43 Vick now works as a free lance music industry consult ant, is a director of the board of PiPA http://www.pipacam paign.com/ and an exciting music tech startup called Delic https://www.delic.net work/ and has also started a PhD on gender diversity in the UK music industry at Queen Mary University of London. Vick was enrolled into the Music Week Women in Music Awards ‘Roll Of Honour’ and BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Music Industry Powerlist. -

Carte Blanche to Gisèle Vienne

STEPHEN O’MALLEY & WUKIR SURYADI Showcase: Carte Blanche to Gisèle Vienne 17/01/2017 • 20:30 • Kaaitheater music/peformance nl/ Theatermaakster Gisèle Vienne kreeg van EUROPALIA INDONESIA carte blanche om zich te verdiepen in de Indonesische cultuur. Samen met Sunn 0)))-stichter Stephen O’Malley trok ze naar Java en Bali om zich onder te dompelen in een magische wereld van performatieve rituelen. Hun ontmoeting met muzikant Wukir Suryadi, stichter van de band Senyawa, resoneerde lang na. Tijdens deze avond laten ze je delen in dat avontuur en de muzikale filosofie die hen verbindt. fr/ EUROPALIA INDONESIA a donné carte blanche à la metteuse en scène Gisèle Vienne pour explorer la culture indonésienne. Gisèle Vienne a voyagé avec Stephen O’Malley, le cofondateur de Sunn O))), à Java et à Bali pour s’immerger dans le monde magique des rituels performatifs. Leur rencontre avec le musicien Wukir Suryadi, cofondateur de Senyawa, a révélé de profondes résonances. Cette soirée présente leur projet commun à travers une philosophie musicale partagée. en/ EUROPALIA INDONESIA gave theatre director Gisèle Vienne carte blanche to explore Indonesian culture. Along with Sunn O))) co-founder Stephen O’Malley she travelled to Java and Bali to immerse herself in the magical world of performative rituals. Their encounter with musician Wukir Suryadi, co-founder of Senyawa, revealed profound resonances. This evening showcases their shared venture through a common musical philosophy. credits co-presented by Kaaitheater, EUROPALIA INDONESIA & Kobalt Works BIOGRAPHIES Stephen O’Malley (b. 1974) was born in New Hampshire, USA and raised in Seattle. He eventually spent a decade in New York and presently is based in Paris. -

CWR Sender ID and Codes

CWR Sender ID Codes CWR06-1972_Specifications_Overview_CWR_sender_ID_and_codes_2021-09-27_EN.xlsx Publisher Submitter Code Submitter Start Date End Date (dd/mm/yyyy) Number (dd/mm/yyyy) To all societies 00 Royal Flame Music Gmbh 104 00585500247 21/08/2015 Rdb Conseil Rights Management 112 00869779543 6/01/2020 Mmp.Mute.Music.Publishing E.K. 468 814224861 25/07/2019 Seegang Musik Musikverlag E.K. 772 792755298 25/07/2019 Les Editions Du 22 Decembre 22D 450628759 4/11/2010 3tone Publishing Limited 3TO 1050225416 25/09/2020 4AD Music Limited 4AD 293165943 15/03/2010 5mm Publishing 5MM 00492182346 22/11/2017 AIR EDEL ASSOCIATES LTD AAL 69817433 7/01/2009 Ceg Rights Usa AAL 711581465 17/12/2013 Ambitious Media Productions AAP 00868797449 31/08/2021 Altitude Balloon AB 722094072 6/11/2013 Abc Digital Distribution Limited ABC 00599510310 8/06/2020 Editions Abinger Sprl ABI 00858918083 23/11/2020 Abkco Music Inc ABM 00056388746 21/11/2018 ABOOD MUSIC LIMITED ABO 420344502 31/03/2009 Alba Blue Music Publishing ABP 00868692763 2/06/2021 Abramus Digital Servicos De Identificacao De Repertorio ABR 01102334131 16/07/2021 Ltda Absilone Technologies ABS 00546303074 5/07/2018 Almo Music of Canada AC 201723811 1/08/2001 2/10/2006 Accorder Music Publishing America ACC 606033489 5/09/2013 Accorder Music Publishing Ltd ACC 574766600 31/01/2013 Abc Frontier Inc ACF 01089418623 20/07/2021 Galleryac Music ACM 00600491389 24/04/2017 Alternativas De Contenido S L ACO 01033930195 17/12/2020 ACTIVE MUSIC PUBLISHING PTY LTD ACT 632147961 16/11/2016 Audiomachine -

Authorized Catalogs - United States

Authorized Catalogs - United States Miché-Whiting, Danielle Emma "C" Vic Music @Canvas Music +2DB 1 Of 4 Prod. 10 Free Trees Music 10 Free Trees Music (Admin. by Word Music Group, 1000 lbs of People Publishing 1000 Pushups, LLC Inc obo WB Music Corp) 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers SESAC Designee 10000 MINUTES 1012 Rosedale Music 10KF Publishing 11! Music 12 Gate Recordings LLC 121 Music 121 Music 12Stone Worship 1600 Publishing 17th Avenue Music 19 Entertainment 19 Tunes 1978 Music 1978 Music 1DA Music 2 Acre Lot 2 Dada Music 2 Hour Songs 2 Letit Music 2 Right Feet 2035 Music 21 Cent Hymns 21 DAYS 21 Songs 216 Music 220 Digital Music 2218 Music 24 Fret 243 Music 247 Worship Music 24DLB Publishing 27:4 Worship Publishing 288 Music 29:11 Church Productions 29:Eleven Music 2GZ Publishing 2Klean Music 2nd Law Music 2nd Law Music 2PM Music 2Surrender 2Surrender 2Ten 3 Leaves 3 Little Bugs 360 Music Works 365 Worship Resources 3JCord Music 3RD WAVE MUSIC 4 Heartstrings Music 40 Psalms Music 442 Music 4468 Productions 45 Degrees Music 4552 Entertainment Street 48 Flex 4th Son Music 4th teepee on the right music 5 Acre Publishing 50 Miles 50 States Music 586Beats 59 Cadillac Music 603 Publishing 66 Ford Songs 68 Guns 68 Guns 6th Generation Music 716 Music Publishing 7189 Music Publishing 7Core Publishing 7FT Songs 814 Stops Today 814 Stops Today 814 Today Publishing 815 Stops Today 816 Stops Today 817 Stops Today 818 Stops Today 819 Stops Today 833 Songs 84Media 88 Key Flow Music 9t One Songs A & C Black (Publishers) Ltd A Beautiful Liturgy Music A Few Good Tunes A J Not Y Publishing A Little Good News Music A Little More Good News Music A Mighty Poythress A New Song For A New Day Music A New Test Catalog A Pirates Life For Me Music A Popular Muse A Sofa And A Chair Music A Thousand Hills Music, LLC A&A Production Studios A. -

La Nouvelle Adresse Performances, Musiques Et Paroles Live Œuvres in Situ, Cinéma

La nouvelle adresse Performances, musiques et paroles live œuvres in situ, cinéma Centre national des arts plastiques 1. Communiqué de presse 5 2. Programme détaillé 7 Vendredi 14 septembre 7 Samedi 15 septembre 7 Dimanche 16 septembre 8 Tout le week-end 8 3. Artistes et œuvres présentés 9 En permanence 9 Vendredi 14 septembre 11 Samedi 15 septembre 12 Dimanche 16 septembre 13 4. 81, rue Cartier-Bresson 15 5. Présentation du Cnap 16 6. Partenaires de La nouvelle adresse 17 Partenaires institutionnels 17 Partenaires médias 17 Autre partenaire 18 7. Visuels disponibles pour la presse 19 8. Informations pratiques 24 Communiqué 1. de presse Visite presse : le vendredi 14 septembre à 17h, en présence des artistes et des commissaires Les 14, 15, 16 septembre, le Centre national des arts scène les vies possibles des œuvres d’art. L’amphithéâtre plastiques (Cnap) ouvre exceptionnellement, avant mobile imaginé par Olivier Vadrot, Cavea, accueille la parole travaux, les portes de sa « nouvelle adresse » à Pantin. d’artistes invités à partager Des images secrètes, images mentales qui viennent peupler fugacement les espaces. Le temps d’un week-end, le Cnap invite à expérimenter le Concerts, performances sonores et playlists diffusés par site : performances, musiques et paroles live, œuvres in situ, L’Écouteur (un salon d’écoute conçu par Jean-Yves Leloup et salon d’écoute et cinéma éphémères participent du bivouac. Laurent Massaloux) font résonner le bâtiment de vibrations Une nuit de fête prolonge la soirée inaugurale. électro-acoustiques, d’hymnes et de confidences. L’art s’immisce pour la première fois dans le bâtiment et La soirée du vendredi 14, élaborée avec le CND, ouvre le Cnap fait ses premiers pas dans son nouveau voisinage les festivités avec une performance inédite de Monster pantinois, en partenariat avec le Centre national de la danse Chetwynd et un concert de Shrouded & The Dinner (CND) et le Centre national édition art image (Cneai). -

Notes from the Underground: a Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music

Notes From The Underground: A Cultural, Political, and Aesthetic Mapping of Underground Music. Stephen Graham Goldsmiths College, University of London PhD 1 I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: …………………………………………………. Date:…………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract The term ‗underground music‘, in my account, connects various forms of music-making that exist largely outside ‗mainstream‘ cultural discourse, such as Drone Metal, Free Improvisation, Power Electronics, and DIY Noise, amongst others. Its connotations of concealment and obscurity indicate what I argue to be the music‘s central tenets of cultural reclusion, political independence, and aesthetic experiment. In response to a lack of scholarly discussion of this music, my thesis provides a cultural, political, and aesthetic mapping of the underground, whose existence as a coherent entity is being both argued for and ‗mapped‘ here. Outlining the historical context, but focusing on the underground in the digital age, I use a wide range of interdisciplinary research methodologies , including primary interviews, musical analysis, and a critical engagement with various pertinent theoretical sources. In my account, the underground emerges as a marginal, ‗antermediated‘ cultural ‗scene‘ based both on the web and in large urban centres, the latter of whose concentration of resources facilitates the growth of various localised underground scenes. I explore the radical anti-capitalist politics of many underground figures, whilst also examining their financial ties to big business and the state(s). This contradiction is critically explored, with three conclusions being drawn. First, the underground is shown in Part II to be so marginal as to escape, in effect, post- Fordist capitalist subsumption.