Evidence for Patterns of Selective Urban Migration in the Greater Indus Valley (2600-1900 BC): a Lead and Strontium Isotope Mortuary Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeozoological Methods

Indian Journal of Archaeology Faunal Remains from Sampolia Khera (Masudpur I), Haryana P.P. Joglekar1, Ravindra N. Singh2 and C.A. Petrie3 1-Department of Archaeology,Deccan College (Deemed University), Pune 411006,[email protected] 2-Department of A.I.H.C. and Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, [email protected] 3-Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, UK, [email protected] Introduction The site of Masudpur I (Sampolia Khera) (29° 14.636’ N; 75° 59.611’) (Fig. 1), located at a distance of about 12 km from the large urban site of Rakhigarhi, was excavated under the Land, Water and Settlement project of the Dept. of Archaeology of Banaras Hindu University and University of Cambridge in 2009. The site revealed presence of Early, Mature and Late Harappan cultural material1. Faunal material collected during the excavation was examined and this is final report of the material from Masudpur I (Sampolia Khera). Fig. 1: Location of Sampolia Khera (Masudpur I) 25 | P a g e Visit us: www.ijarch.org Faunal Remains from Sampolia Khera (Masudpur I), Haryana Material and Methods Identification work was done at Banaras Hindu University in 2010. Only a few fragments were taken to the Archaeozoology Laboratory at Deccan College for confirmation. After the analysis was over select bones were photographed and all the studied material was restored back to the respective cloth storage bags. Since during excavation archaeological material was stored with a context number, these context numbers were used as faunal analytical units. Thus, in the tables the original data are presented under various cultural units, labelled as phases by the excavators (Table 1). -

Government of India Ground Water Year Book of Haryana State (2015

CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE (2015-2016) North Western Region Chandigarh) September 2016 1 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVINATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF HARYANA STATE 2015-2016 Principal Contributors GROUND WATER DYNAMICS: M. L. Angurala, Scientist- ‘D’ GROUND WATER QUALITY Balinder. P. Singh, Scientist- ‘D’ North Western Region Chandigarh September 2016 2 FOREWORD Central Ground Water Board has been monitoring ground water levels and ground water quality of the country since 1968 to depict the spatial and temporal variation of ground water regime. The changes in water levels and quality are result of the development pattern of the ground water resources for irrigation and drinking water needs. Analyses of water level fluctuations are aimed at observing seasonal, annual and decadal variations. Therefore, the accurate monitoring of the ground water levels and its quality both in time and space are the main pre-requisites for assessment, scientific development and planning of this vital resource. Central Ground Water Board, North Western Region, Chandigarh has established Ground Water Observation Wells (GWOW) in Haryana State for monitoring the water levels. As on 31.03.2015, there were 964 Ground Water Observation Wells which included 481 dug wells and 488 piezometers for monitoring phreatic and deeper aquifers. In order to strengthen the ground water monitoring mechanism for better insight into ground water development scenario, additional ground water observation wells were established and integrated with ground water monitoring database. -

Dating the Adoption of Rice, Millet and Tropical Pulses at Indus Civilisation

Feeding ancient cities in South Asia: dating the adoption of rice, millet and tropical pulses in the Indus civilisation C.A. Petrie1,*, J. Bates1, T. Higham2 & R.N. Singh3 1 Division of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, UK 2 RLAHA, Oxford University, Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK 3 Department of AIHC & Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, India * Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) <OPEN ACCESS CC-BY-NC-ND> Received: 11 March 2016; Accepted: 2 June 2016; Revised: 9 June 2016 <LOCATION MAP><6.5cm colour, place to left of abstract and wrap text around> The first direct absolute dates for the exploitation of several summer crops by Indus populations are presented. These include rice, millets and three tropical pulse species at two settlements in the hinterland of the urban site of Rakhigarhi. The dates confirm the role of native summer domesticates in the rise of Indus cities. They demonstrate that, from their earliest phases, a range of crops and variable strategies, including multi-cropping were used to feed different urban centres. This has important implications for our understanding of the development of the earliest cities in South Asia, particularly the organisation of labour and provisioning throughout the year. Keywords: South Asia, Indus civilisation, rice, millet, pulses Introduction The ability to produce and control agricultural surpluses was a fundamental factor in the rise of the earliest complex societies and cities, but there was considerable variability in the crops that were exploited in different regions. The populations of South Asia’s Indus civilisation occupied a climatically and environmentally diverse region that benefitted from both winter and summer rainfall systems, with the latter coming via the Indian summer monsoon (Figure 1; Wright 2010; Petrie et al. -

Budget 2020: Rakhigarhi to Hastinapur, Why You Should Visit These Archaeological Sites

Budget 2020: Rakhigarhi to Hastinapur, why you should visit these archaeological sites indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/destination-of-the- February 2, 2020 Sivasagar and Dholavira (Source: Aateesh Bangia/Wikimedia Commons, benonsane/Instagram, Image designed by Rajan Sharma) Budget 2020: Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman proposed to develop five archaeological sites across India with on-site museums, as part of the Union Budget 2020-21. The places include Rakhigarhi in Haryana, Hastinapur in Uttar Pradesh, Sivasagar in Assam, Dholavira in Gujarat and Adichanallur in Tamil Nadu. With remains of ancient civilisations to relics of royal opulence, these archaeological sites are also attractive tourists destinations. And if you are a fan of historical places and monuments, these sites should be added to your bucket list. Rakhigarhi, Haryana Rakhigarhi (Source: rakhigarhi/Instagram) Located in the Hisar district of Haryana, Rakhigarhi is known to be a site of pre-Harappan Civilisation settlement, and later a part of the ancient civilisation itself, between 2600-1900 BCE. Excavated by Amarendra Nath of Archaeological Survey of India, the site revealed remnants of a planned township with mud-brick houses and proper drainage system, according to the official site of Haryana Tourism, along with terracotta jewellery, conch shells, vase and seals, things the Harappans were known for. Hastinapur, Uttar Pradesh Ashtapad Tirth Jain Mandir (Source: bhanupratapjoshi/Instagram) We know Hastinapur as the ancient capital city of Pandavas and Kauravas from the epic Mahabharata. Naturally, it is the abode of princely anecdotes and royal conquests. Excavations at Hastinapur reportedly began in 1950-52 on behalf of the Archaeological Survey of India and the items found included arrows, spearheads, shafts, tongs, hooks, axes and knives, amounting to about 135 iron objects. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Rohtak, Part XII-A & B

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES-8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE &TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT ROHTAfK v.s. CHAUDHRI DI rector of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, ]993 HARYANA DISTRICT ROHTAK Km5 0 5 10 15 10Km bLa:::EL__ :L I _ b -~ (Jl o DISTRICT ROHTAK CHANGE IN JURISDICTION 1981-91 z Km 10 0 10 Km L-.L__j o fTI r BOUNDARY, STATE! UNION TERRi10RY DIS TRICT TAHSIL AREA GAINED FROM DISTRIC1 SONIPAT AREA GAINED FROM DISTRICT HISAR \[? De/fl/ ..... AREA LOST TO DISTRICT SONIPAT AREA LOST TO NEWLY CREATED \ DISTRICT REWARI t-,· ~ .'7;URt[oN~ PART OF TAHSIL JHAJJAR OF ROHTAK FALLS IN C.D,BLO,CK DADRI-I . l...../'. ",evA DISTRICT BHIWANI \ ,CJ ~Q . , ~ I C.D.BLOCK BOUNDARY "- EXCLUDES STATUTORY ~:'"t -BOUNDARY, STATE I UNION TERRITORY TOWN (S) ',1 DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED TAHSIL. UPTO I. 1.1990 C.D.BLOCK HEADQUARTERS '. DISTRICT; TAHSIL; C. D. BLOCK. NATIONAL HIGHWAY STATE HIGHWAY SH 20 C. O. BLOCKS IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD RS A MUNDlANA H SAMPLA RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION, BROAD GAUGE IiiiiI METRE GAUGE RS B GOHANA I BERI CANAL 111111""1111111 VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME Jagsi C KATHURA J JHAJJAR URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE-CLASS I,!I,lII, IV & V" ••• ••• 0 LAKHAN MAJRA K MATENHAIL POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE PTO DEGREE COLLEGE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION .. [liiJ C'a E MAHAM L SAHLAWAS REST ClOUSE, TRAVELLERS' BUNGALOW' AND CANAL BUNGALOW RH, TB, CB F KALANAUR BAHADURGARH Other villages having PTO IRH/TBIC8 ~tc.,are shown as. -

List of State Govt Employees Retiring Within One Year

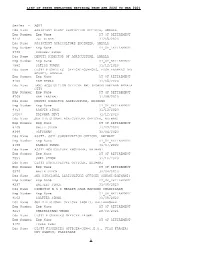

LIST OF STATE EMPLOYEES RETIRING FROM APR 2020 TO MAR 2021 Series - AGRI Ddo Name ASSISTANT PLANT PROTECTION OFFICER, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 9312 JAI SINGH 31/05/2020 Ddo Name ASSISTANT AGRICULTURE ENGINEER, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6738 SUKHDEV SINGH Ddo Name DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 7982 SATISH KUMAR 31/12/2020 Ddo Name DISTT FISHERIES OFFICER-CUM-CEO, FISH FARMERS DEV AGENCY, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8166 RAM NIWAS 31/05/2020 Ddo Name LAND ACQUISITION OFFICER PWD (POWER)HARYANA AMBALA CITY Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8769 RAM PARSHAD 31/08/2020 Ddo Name DEPUTY DIRECTOR AGRICULTURE, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 9753 RANVIR SINGH 31/12/2020 10203 KRISHNA DEVI 31/12/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVISIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8105 DALIP SINGH 31/07/2020 8399 SATYAWAN 30/04/2020 Ddo Name ASSTT. SOIL CONSERVATION OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6799 RAMESH KUMAR 31/07/2020 Ddo Name ASSTT AGRICULTURE ENGINEER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 7593 SHER SINGH 31/10/2020 Ddo Name DISTT HORTICULTURE OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6576 WAZIR SINGH 30/04/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVSIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER SIWANI(BHIWANI) Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8237 BALJEET SINGH 31/05/2020 Ddo Name DIRECTOR E S I HEALTH CARE HARYANA CHANDIGARH Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8562 CHATTER SINGH 30/09/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVISIONAL -

Dating the Adoption of Rice, Millet and Tropical Pulses at Indus Civilisation Settlements

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Feeding ancient cities in South Asia: dating the adoption of rice, millet and tropical pulses in the Indus civilisation C.A. Petrie1,*, J. Bates1, T. Higham2 & R.N. Singh3 1 Division of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, UK 2 RLAHA, Oxford University, Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK 3 Department of AIHC & Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, India * Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) The first direct absolute dates for the exploitation of several summer crops by Indus populations are presented. These include rice, millets and three tropical pulse species at two settlements in the hinterland of the urban site of Rakhigarhi. The dates confirm the role of native summer domesticates in the rise of Indus cities. They demonstrate that, from their earliest phases, a range of crops and variable strategies, including multi-cropping were used to feed different urban centres. This has important implications for our understanding of the development of the earliest cities in South Asia, particularly the organisation of labour and provisioning throughout the year. Keywords: South Asia, Indus civilisation, rice, millet, pulses SI.1. Chronology of the Indus civilisation The urban phase (c. 2600–1900BC) of the Indus civilisation was characterised by urban centres surrounded by fortification walls or built on platforms; houses, drains and wells made of mud- and/or fired-brick; a distinctive material culture assemblage marked by complex craft products; an un-translated script; and evidence for long-range interaction with other complex societies in Western and Central Asia (Marshall 1931; Piggott 1950; Sankalia 1962; Wheeler 1963; Allchin & Allchin 1968, 1982, 1997; Fairservis 1971; Chakrabarti 1995, 1999, 2006; Lal 1997; Kenoyer 1998; Possehl 2002; Agrawal 2007; Wright 2010; Petrie 2013). -

Llisar Founded by Ficuz Shah Tughlaq About AD 1354.1 Accord

The name of the district is derived . from its headquarters town, 'llisar founded by Ficuz Shah Tughlaq about A. D. 1354.1 According .to V. S. Agrawala, Aisukari or Isukara, a beautiful and prosperous city .01 Kuru Janapada referred to by Panini, was the ancient name of ;1tsar;2 However, the antiquity of the area can be established on the basis of the discovery of pre-historic and historical sites at a number of places in the district.3 Some of the most prominent sites are Bana- 'waIi,Rakhigarhi, Seeswal, Agroha and Hansi. 1. Anf, Tarikh-i-Firozshahi. (Hindi Tr.) S.A.B. Rizvi, Tughlaq Kalina 'Bharat ~rh. 1957, II,PP. 73,5. 2. V. S. Agrawala. Panini Kalina Bharatavarsha, (Hindi) Sam. 2012, p. '86; Penini'. Ashtadhyavi,4/2/54. J. For details of th~ :explorations and excavations reference may be made to the f.allowing :- (i) A. Cunningham, Archaeological Survey 0/ India Reports, V, 1872-73. Calcutta, 1875. (ii) C. Rodgers, ,Archaeological Survey 0/ India, Reports 0/ the Puttiab Circle, 1888-89, Calcutta, 1891. (Hi) H. L. SrivastavlJ, Excavations at Agroha, Memoirs 0/ the ArchaeolQgical Survey 0/ India, No. 61, Delhi, 1952. (iv) R. S. Bisht, Excavations ••.at Banawali: 1974-77. Proceedings.o/ the Seminar on H arappan Culture in the Indo-Pak Sub-continent. Srinagar 1978. ('V) SwarajEhan, (a) Pre-historical Archaeology 0/ the Sarasvati and the c',<Drishadvati Valleys. -Baroda University. Ph. D. Dissertation, 1971, MSS. ExeavatiolfS at Mitothal (1968) and other exploratio11S in the Sutlej-Yamuna Divide, Kurukshetra, 1975. (C) Siswa! : A Pre-Harappan Site in Haryana, Purataltva, 1972. -

Rakhigarhi: a Harappan Metropolis in the Sarasvati-Drishadvati Divide

Bulletin of the Indian Archaeological Society No. 28 1997-98 Editors K. N. Dikshit & K.S. Ramachandran O.K. Printworld {P} Ltd. New Delhi Rakhigarhi: A Harappan Metropolis in the Sarasvati-Drishadvati Divide AMARENORA NAni· In th Harappan dynamics, Rakhigarhi (29' 16' Nand meant Rakhikhas) conlllined both Early or Pre-Harappan ,760 10' E), in tehsil NamauJ, District Hissar, Haryana is and Harappan culture horizons; Rakhi Shahpur only wit 2 next only to Dholavira in Kutch (Gujarat). The site can be nessed the M:llure phase of Harappan , But in an appen approached from Delhi via Rohtak, Hansi and lind. lind, dix to hi s report on Milathal', he recorded, Rnkhi Shahpur besides being the nearest railhead for the site on Delhi as Rakhigarhi and saw them as 'twin sites', He missed Bhatinda section of the Northern Railway, provides me complelely the presence of the other three mounds noted shonest road link through Gulkani or Namaul. 11lere is a above. In the early seventies, SHak: Ram" paid a visit to regular Haryana Roadways bus service from lind and the site and reponed, besides other Harappan antiquities, a seal, presently boused in the Gurukul Museum at lhaijar Haasi to Rakhigarhi . Private conveyances are also ayail ~ able from Narnaul. The nearest guest house of the (Haryana). He too noticed Early or Pre-Harappan and Harappan elements at the sileo Sut in the early eighties a Irrigation department is at Rajthal. team of archaeologists from the Depanment of Archaeology and Museums, < Haryana noticed late . Over the Harappan mounds are the thickly populated Harappan elements here' which was later got endorsed by villages of Latc Mediaeval times. -

Oilseeds, Spices, Fruits and Flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 24 (2019) 879–887 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Oilseeds, spices, fruits and flavour in the Indus Civilisation T J. Bates Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The exploitation of plant resources was an important part of the economic and social strategies of the people of South Asia the Indus Civilisation (c. 3200–1500 BCE). Research has focused mainly on staples such as cereals and pulses, for Prehistoric agriculture understanding these strategies with regards to agricultural systems and reconstructions of diet, with some re- Archaeobotany ference to ‘weeds’ for crop processing models. Other plants that appear less frequently in the archaeobotanical Indus Civilisation record have often received variable degrees of attention and interpretation. This paper reviews the primary Cropping strategies literature and comments on the frequency with which non-staple food plants appear at Indus sites. It argues that Food this provides an avenue for Indus archaeobotany to continue its ongoing development of models that move beyond agriculture and diet to think about how people considered these plants as part of their daily life, with caveats regarding taphonomy and culturally-contextual notions of function. 1. Introduction 2. Traditions in Indus archaeobotany By 2500 BCE the largest Old World Bronze Age civilisation had There is a long tradition of Indus archaeobotany. As summarised in spread across nearly 1 million km2 in what is now Pakistan and north- Fuller (2002) it can be divided into three phases: ‘consulting palaeo- west India (Fig. -

Download Book

EXCAVATIONS AT RAKHIGARHI [1997-98 to 1999-2000] Dr. Amarendra Nath Archaeological Survey of India 1 DR. AMARENDRA NATH RAKHIGARHI EXCAVATION Former Director (Archaeology) ASI Report Writing Unit O/o Superintending Archaeologist ASI, Excavation Branch-II, Purana Qila, New Delhi, 110001 Dear Dr. Tewari, Date: 31.12.2014 Please refer to your D.O. No. 24/1/2014-EE Dated 5th June, 2014 regarding report writing on the excavations at Rakhigarhi. As desired, I am enclosing a draft report on the excavations at Rakhigarhi drawn on the lines of the “Wheeler Committee Report-1965”. The report highlights the facts of excavations, its objective, the site and its environment, site catchment analysis, cultural stratigraphy, structural remains, burials, graffiti, ceramics, terracotta, copper, other finds with two appendices. I am aware of the fact that the report under submission is incomplete in its presentation in terms modern inputs required in an archaeological report. You may be aware of the fact that the ground staff available to this section is too meagre to cope up the work of report writing. The services of only one semiskilled casual labour engaged to this section has been withdrawn vide F. No. 9/66/2014-15/EB-II496 Dated 01.12.2014. The Assistant Archaeologist who is holding the charge antiquities and records of Rakhigarhi is available only when he is free from his office duty in the Branch. The services of a darftsman accorded to this unit are hardly available. Under the circumstances it is requested to restore the services of one semiskilled casual labour earlier attached to this unit and draftsman of the Excavation Branch II Purana Quila so as to enable the unit to function smoothly with limited hands and achieve the target. -

Assorted Dimensions of Socio-Economic Factors of Haryana

ISSN (Online) : 2348 - 2001 International Refereed Journal of Reviews and Research Volume 6 Issue 6 November 2018 International Manuscript ID : 23482001V6I6112018-08 (Approved and Registered with Govt. of India) Assorted Dimensions of Socio-Economic Factors of Haryana Nisha Research Scholar Department of Geography Sri Venkateshwara University, Uttar Pradesh, India Dr. Avneesh Kumar Assistant Professor Department of Geography Sri Venkateshwara University Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract It was carved out of the former state of East Punjab on 1 November 1966 on a linguistic basis. It is ranked 22nd in terms of area, with less than 1.4% (44,212 km2 or 17,070 sq mi) of India's land area. Chandigarh is the state capital, Faridabad in National Capital Region is the most populous city of the state, and Gurugram is a leading financial hub of the NCR, with major Fortune 500 companies located in it. Haryana has 6 administrative divisions, 22 districts, 72 sub-divisions, 93 revenue tehsils, 50 sub-tehsils, 140 community development blocks, 154 cities and towns, 6,848 villages, and 6222 villages panchayats. As the largest recipient of investment per capita since 2000 in India, and one of the wealthiest and most economically developed regions in South Asia, Registered with Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Govt. of India URL: irjrr.com ISSN (Online) : 2348 - 2001 International Refereed Journal of Reviews and Research Volume 6 Issue 6 November 2018 International Manuscript ID : 23482001V6I6112018-08 (Approved and Registered with Govt. of India) Haryana has the fifth highest per capita income among Indian states and territories, more than double the national average for year 2018–19.