Symposium on Daniel Letwin: the Challenge of Interracial Unionism*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctnnur RESUME

t, DoctnnurRESUME 3D 125 446 'HI 00S :018 1 S AUTHOR Garfin, !folly, Ed.; And Others TITLE Collective Bargaining in Higher Education. Bibliography No. 4... ' .. INSTITUTION 'City Univ. of New York, NY. Bernard Baruch Coll. NationalCenter for the Study of Collective Bargaining 4 HigherEdication. PUB DA/E Apr 7,6 , . NOTE 241p. AVAILABrZ FROM National Center for Collective Bargaining in Higher Education,, Baruch College (CUiY), New York, N.Y. ($7.00) EDRS PRICE" NF -$0.83 Plus Postage-. HC Not Aiailable fron.EDRS. AESCRITQRS Academic Freedom; Administration; Affirmative Action; Attitudes; *Bibliogriphies; *dbllective Bargaining; Court Cases; Educational Accountability; *Employer Employee Relationship; *Employment Problems; Fringe Benefits; Governance; Grievance Procedures; *Higher Education; Job Layoff; Legislation; Personnel Policy; Post Secondary Edutation; Salaries;. Strikes; Students; Teaching Load,;' Tenure; Unions I . , ABSTRACT , The fourth annual bibliography of retrospective and . current searches in the field of collective bargaining in higher education represents an attempt. to'survey the literature of the field as it relates to faculty in public or private colleges and ,universitieS. The scope includes 1975 and pre-1975 references. Relevant information from major journals plus' Material relevant to arbitiation'awards, courtdecisions, NLRB, and PERK rulings are included. The bibliography, Arranged alphabetically:by subject, includes topics on:, academic freedom4 administration, collectiVe bargaining in Canada; faculty attitudes, -

Blueprint to Empower Workers for Shared Prosperity

Blueprint to Empower Workers for Shared Prosperity Report by Richard Kirsch, Dorian Warren, and Andy Shen October 7, 2015 Until economic and social rules work for all Americans, they’re not working. Inspired by the legacy of Franklin and Eleanor, Roosevelt Institute reimagines America as it should be — a place where hard work is rewarded, everyone participates, and everyone enjoys a fair share of our collective prosperity. We believe that when the rules work against this vision, it’s our responsibility to recreate them. We bring together thousands of thinkers and doers — from a new generation of leaders in every state to Nobel laureate economists — work to redefine the rules that guide our social and economic realities. We rethink and reshape everything from local policy to federal legislation, orienting toward a new economic and political system, one built by many for the good of all. For media inquiries, please contact Chris Linsmayer at 720 212-4883 or [email protected]. The Roosevelt Institute’s Future of Work initiative focuses on three areas: promoting innovative strategies for worker organizing and representation, strengthening labor standards and their enforcement, and assuring access to good jobs for women, workers of color and immigrants. Future of Work brings together thought and action leaders from multiple fields to reimagine a 21st century social contract that expands workers’ rights and the number of living wage jobs. The aim is to aggregate and support the development of innovative policies and organizing models and to disseminate that vision to opinion leaders, policymakers, and to the broader public. The Future of Work initiative is led by Roosevelt Institute Fellows Annette Bernhardt, Richard Kirsch, and Dorian Warren. -

Vocabulaire Français-Anglais Des Relations Professionnelles Glossary of Terms Used in Industrial Relations

Document generated on 09/25/2021 12:32 p.m. Relations industrielles Industrial Relations Vocabulaire français-anglais des relations professionnelles Glossary of Terms Used in Industrial Relations Vocabulaire français-anglais des relations professionnelles Glossary of Terms used in Industrial Relations (English-French) Volume 27, Number 1-2, 1972 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/028297ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/028297ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Département des relations industrielles de l'Université Laval ISSN 0034-379X (print) 1703-8138 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document (1972). Vocabulaire français-anglais des relations professionnelles. Relations industrielles / Industrial Relations, 27(1-2), 11–277. https://doi.org/10.7202/028297ar Tous droits réservés © Département des relations industrielles de l'Université This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Laval, 1972 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ I VOCABULAIRE FRANÇAIS - ANGLAIS DES RELATIONS PROFESSIONNELLES VOCABULAIRE FRANÇAIS-ANGLAIS abandon-accidents 13 A abandon (taux m d') — quit rate; abstentionnisme f — abstentionism drop-out rate abstentionniste m — abstentionist abandon m volontaire d'emploi — Abstention résignation; voluntary séparation; abus m de droit — abuse of rights; quit; voluntary termination ofemploy- abuse of privilèges; mi su se of law; ment breach of law Syn. -

Patriotism and Its Discontents: a Small Town in a Great Strike I

Patriotism and its discontents: a small town in a great strike i Julie Kimber Lecturer in Politics Social & Policy Studies Faculty of Life and Social Sciences Swinburne University of Technology Mail H31 PO Box 218 Hawthorn VIC 3122 Australia Email: [email protected] Tel: + 61 3 9214 8103 Fax: + 61 3 9819 0574 1 Patriotism and its discontents: a small town in a great strike Julie Kimber* Much ink has been spilt on the question of the General Strike of 1917. Despite nuances of interpretation there exists a general consensus that the strike was a product of the deeply disruptive social, economic and political circumstances of World War I. This paper seeks to add to that discussion through a vignette of the strike, as it played out in the town of Orange in central western NSW. The battle for the meaning of words unleashed during the period illustrates the now well- known fault lines of power and social control embedded in Australia. The 1917 Strike cannot be studied in isolation from World War I. As Dan Coward argued the reaction to the strike ‘reflected a corrosive social and political malaise’ then prevalent (Coward, 1973, p. 80). Despite differing nuances, a historiographical consensus exists on the particularly brutal effects of the processes of the war (see, for example, Gollan, 1963; Turner, 1965; Coward, 1973; Taksa, 1991; and Bollard, 2006). The conscription referenda campaigns, punctuated by the General Strike, lifted the veil of consensus, created new social fractures and entrenched divisions between political parties. It purged these parties of marginal supporters, removing the cross-class nature of organisations in infancy. -

Teamsters Amsters

Teamsters http://www.enotes.com/topic/Teamsters Teamsters International Brotherhood of Teamsters Founded 1903 Members 1,402,878 (2008)[1] Country United States and Canada Change to Win Federation and Canadian Affiliation Labour Congress Key people James P. Hoffa, General President Office Washington, D.C. location Website www.teamsters.org The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) is a labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of several local and regional locals of teamsters, the union now represents a diverse membership of blue-collar and professional workers in both the public and private sectors. The union had approximately 1.4 million members in 2008.[1] Formerly known as the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America, the IBT is a member of the Change to Win Federation and Canadian Labour Congress. Contents 1 History o 1.1 Early history o 1.2 Organizing and growth during the Great Depression o 1.3 World War II and the post-war period o 1.4 The influence of organized crime o 1.5 The rise, fall and disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa o 1.6 Decentralization, deregulation and drift o 1.7 Internal and external challenges o 1.8 Recent history 2 Political donations 3 Strikes 4 Organization o 4.1 General President o 4.2 Membership o 4.3 Divisions 5 See also 6 Notes 7 References 8 External links History Early history The American Federation of Labor (AFL) had helped form local unions of teamsters since 1887. In November 1898, the AFL organized the Team Drivers' International Union (TDIU).[2][3] In 1901, a group of Teamsters in Chicago, Illinois, broke from the TDIU and formed the Teamsters National Union.[2] The new union permitted only employees, teamster helpers, and owner-operators owning only a single team to join, unlike the TDIU (which permitted large employers to be members), and was more aggressive than the TDIU in advocating higher wages and shorter hours.[2] Claiming more than 28,000 members in 47 locals, its president, Albert Young, applied for membership in the AFL. -

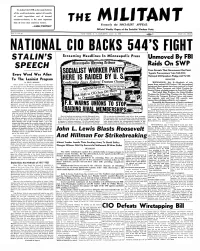

Stalin's Speech: Not a Proletarian Note in It

NATIONAL CIO BACKS 5 4 4 ’S FIGHT STALIN’S Screaming Headlines In Minneapolis Press Unmoved By FBI SPEECH Raids On SWP Press Reveals T h a t G overnm ent Had Sent 'Agents Provocateurs' Into 544-CIO; Every Word Was Alien National CIO Speakers Pledge Aid To 544 BULLETIN To The Leninist Program i By FELIX MORROW MINNEAPOLIS, July 8— Hundreds of tele Stalin’s speech of July 3rd was successful in its main objec grams from national CIO leaders, CIO international tive. It sought to assure Washington and London that the Krem unions and local unions, have been received by Local lin would conduct the war against Germany within political lim its 544-CIO, Motor Transport and Allied Workers In entirely acceptable to “democratic” capitalism. There would be dustrial Union, pledging support to Local 544’s fight. no summoning the great masses of Europe to the overthrow of The United Mine Workers, the United Rubber capitalism, breeder of fascism. There would be no pledges to the Workers, the United Shoe Workers, the Die Casting German proletariat against a second and worse Versailles. The Workers, the Transport Workers Union, and numer Soviet Union would not fight a revolutionary war as it did in ous regional, state and local CIO councils were 1918-1921 against the imperialist interventionists, but would lim it itself to methods acceptable to its imperialist allies. Such were among those pledging solidarity and support. the assurances which Stalin gave by his speech; and they were Meanwhile the Department of Justice continued understood very well by the class-conscious bourgeoisie. -

PICKETING by an UNCERTIFIED UNION: the NEW SECTION 8(B)(7)*

NOTES AND COMMENTS PICKETING BY AN UNCERTIFIED UNION: THE NEW SECTION 8(b)(7)* THE union picket line, traditionally one of labor's most potent weapons in its competitive struggle with management, was subjected by Congress to new federal controls in the 1959 amendments to the national labor acts.' Together with other forms of concerted union activities, picketing was free from federal *An earlier version of this Comment was submitted in satisfaction of the writing re- quirement of the Yale Law School's Divisional Program, Labor Law Division, 1959-1960. The Law JorLnzd wishes to thank Professors Clyde NV. Summers and Harry H. Welling- ton for bringing this paper to the Editors' attention. 1. The Labor-Wanagement Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 (LMRDA), § 704 (c), 73 Stat. 544, 29 U.S.CA. § 158(e) (Supp. 1959), added a new union unfair labor practice, § 8(b) (7), to the National Labor Relations (Wagner) Act § 8, 49 Stat. 449 (1935), as amended, Labor-Management Relations (Taft-Hartley) Act 61 Stat. 141 (1947), 29 U.S.C. § 158 (1958): [8(b) (7)] to picket or cause to be picketed, or threaten to picket or cause to be picketed, any employer where an object thereof is forcing or requiring an emp!oyer to recognize or bargain with a labor organization as the representative of his em- ployees, or forcing or requiring the employees of an employer to accept or select such labor organization as their collective bargaining representative, unless such labor organization is currently certified as the representative of such employees: (A) where the -

USW-11-03.Pdf

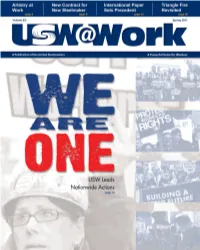

INSIDEUSW@WORK Rebuilding America’s manufacturing base is “ central to rebuilding our nation’s economy. Richard Trumka AFL-CIO President, May 4, 2011 ” INTERNATIONAL EXECUTIVE BOARD Leo W. Gerard International President Stan Johnson Int’l. Secretary-Treasurer 04 08 Thomas M. Conway Int’l. Vice President ARTISTRY IN METAL RG STEEL (Administration) USW members working for Wendell August Some 6,000 USW members have ratified Forge maintain a tradition of quality craftsman- a contract with newly-formed RG Steel, Fred Redmond ship at the decorative metalwork business, which which purchased facilities from Severstal, Int’l. Vice President burned to the ground a year ago in 2010. the Russian steelmaker. (Human Affairs) Ken Neumann Nat’l. Dir. for Canada Jon Geenen Int’l. Vice President Gary Beevers 12 14 Int’l. Vice President INTERNATIONAL PAPER WE ARE ONE USW members at 15 local unions at Inter- The USW participated in multiple rallies on Carol Landry national Paper Co. mill locations overwhelmingly April 4 as part of the AFL-CIO’s “We Are One” Vice President at Large ratified a new four-year contract that covers campaign, meant to pay tribute to Dr. Martin 6,000 workers and sets a bargaining standard. Luther King Jr. and his fight for social justice. DIRECTORS FEATURES ON THE COVER David R. McCall, District 1 Speaking Out 03 Union activists participate in USW-led rallies across the country. Michael Bolton, District 2 CAPITOL LETTERS 33 News Bytes 34 Stephen Hunt, District 3 William J. Pienta, District 4 Daniel Roy, District 5 Wayne Fraser, District 6 Jim Robinson, District 7 Ernest R. -

Political Activism and Workplace Industrial Relations in a UK ‘Failing’ School

Political Activism and Workplace Industrial Relations in a UK ‘Failing’ School Moira Calveley and Geraldine Healy Abstract The paper draws on a qualitative case study of workplace industrial relations in an inner- city secondary school identified as ‘failing’ and subsequently closed. It considers the way unionized teachers and their representatives interpret, influence and resist the impact of centralized managerial and educational change. The local implementation of such change leads to an engagement with the debates on union renewal. In particular, the paper explores the dynamic interrelationship between political and trade union activism and the tension between workplace relations and formal union organization. 1. Introduction The paper explores the relationship between trade union activists, their members and their union in ‘Parkville’1, a UK inner-city secondary school, identified as ‘failing’ and subsequently closed. The impact of new managerialism on workplace activism is considered showing how decentralized management initiatives inflamed industrial relations tensions at school level, how teachers collectively resisted new managerialism, and, importantly, how this resistance was fuelled by a local union activist, also a political activist. By engaging with the union renewal debate, the paper draws attention to the neglected link between trade union activism and political activism, and in this context revisits the uneasy relationship between unions as representative organizations and as oligarchies. Finally, the extent to which conditions in the school promote or hinder union renewal, resilience and, as it emerges, degrees of retreat is explored. The paper is set against the backdrop of radical educational reform in England and Wales. The 1988 Education Reform Act (ERA) introduced ‘centralized decentralization’ (Hoggett 1996: 18) into education through centralized curriculum control and a devolved system of management through the local management of schools (LMS). -

Where the Heart Is? a Geographic Analysis of Working-Class Cultures

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu There have been many attempts to understand how urban residence and factory organization lead groups of workers to realize and act upon their political interests (Gordon 1977; Katznelson 1981; Thompson 1966; Guttman 1987). Marx and Engels suggested that the physical concentration of workers in cities and large factories contributed to their ability to realize class (as opposed to individual) interests (Marx 1977, pp. 455-457). In addition, students of political behavior (Lazarsfeld, Berelson and Caudet [1944] 1968; Berelson, Lazarsfeld and McPhee 1954; Tingsten [1937]1963; Huckfeldt 1986) have identified a clustering or concentration effect of workers' residential patterns on patterns of neighborhood voting: the higher the concentration of workers, the more likely the geographical area is to produce a strong left vote. The higher left vote is not attributed solely to workers' individual propensity to vote left, but also to their collective ability to shape the political views of others living in their neighborhoods. Still, despite often militant clashes between workers and owners on the shop floor of American factories, historians of the American labor movement have noted the general tendency of working-class actions to be restricted to the workplace, isolated from the communities in which workers live (Taft and Ross 1969; Shefter 1986; Bridges 1986). For example, actions such as strikes and sit-ins at work put workers in direct conflict with managerial authority. Such conflicts at work might have led American workers to question conventional views of political power and to support socialist or other left-wing parties, as they have elsewhere. -

![PUB DATE [75] CONTRACT NIE-C-74-0107 NOTE 131P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2122/pub-date-75-contract-nie-c-74-0107-note-131p-10812122.webp)

PUB DATE [75] CONTRACT NIE-C-74-0107 NOTE 131P

DOCUMENT RESUME a ED 106 517 CE 003 685 AUTHOR Levine, Herbert A. TITLE Strategies for the Application of Foreign Legislation on Paid Educational Leave to the United States Scene. INSTITUTION National Inst. of Education (DHEN), Vashingtca, D.C. Career Education Program. PUB DATE_ [75] CONTRACT NIE-C-74-0107 NOTE 131p. EDRS PRICE NF -$0.76 HC-$6.97 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Adult Education Programs; Adult Vocational Education; Cooperative Planning; Educational Legislation; *Educational Needs; *Educational Opportunities; Federal Legislation; Financial Support; Foreign Countries; Industrial Training; International Organizations; Labor Education; *Leave of Absence; *Legislation; School Industry Relationship; State Legislation; Supplementary Education IDENTIFIERS *Educational Leave ABSTRACT The paper discusses both European and American approaches to providing and funding recurrent educational opportunities for workers and their families. A section covers actions and studies of international organizations regarding paid educational leave and European attempts to increase educational opportunities through national and State legislation, private practice, and collective bargaining. A major portion outlines in detail educational plans of American companies and international unions; other sections discuss policy recommendations and strategies for implementation in the United States. Three basic recommendations are made: for a coalition among the educational world and the worlds of industry and labor (requiring a vehicle for communication among labor, management, government, and education); for agreement between labor and management prior to adoption of national or regional legislation; and for effective representation of the formal education system in such a coalition., Conclusions point out the paradoxical need for more expenditure on recurrent education in a time of economic crisis, and call for National Institute of Education aid in coordination, planning, and research in the United States. -

Vocabulaire Français-Anglais Des Relations Professionnelles / Glossary of Terms Used in Industrial Relations »

« Vocabulaire français-anglais des relations professionnelles / Glossary of Terms Used in Industrial Relations » [s.a.] Relations industrielles / Industrial Relations, vol. 27, n° 1-2, 1972, p. 11-277. Pour citer ce document, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/028297ar DOI: 10.7202/028297ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 21 juin 2016 09:38 I VOCABULAIRE FRANÇAIS - ANGLAIS DES RELATIONS PROFESSIONNELLES VOCABULAIRE FRANÇAIS-ANGLAIS abandon-accidents 13 A abandon (taux m d') — quit rate; abstentionnisme f — abstentionism drop-out rate abstentionniste m — abstentionist abandon m volontaire d'emploi — Abstention résignation; voluntary séparation; abus m de droit — abuse of rights; quit; voluntary termination ofemploy- abuse of privilèges; mi su se of law; ment breach of law Syn. - Démission; départ volontaire accélération f — speed-up abondance (société f d') — affluent So Syn. - Cadence accélérée; rythme accéléré; ciety cadence infernale abrogation f de convention — abroga accès m aux livres — access to books tion of agreement; termination of and records agreement accès m aux terrains et locaux de Syn.