Art 1 Vol V Is 1.Rtf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermeneutics: a Literary Interpretive Art

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Hermeneutics: A Literary Interpretive Art David A. Reitman The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3403 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] HERMENEUTICS: A LITERARY INTERPRETATIVE ART by DAVID A. REITMAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 DAVID A. REITMAN All Rights Reserved ii Hermeneutics: A Literary Interpretative Art by David A. Reitman This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date George Fragopoulos Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Hermeneutics: A Literary Interpretative Art by David A. Reitman Advisor: George Fragopoulos This thesis examines the historical traditions of hermeneutics and its potential to enhance the process of literary interpretation and understanding. The discussion draws from the historical emplotment of hermeneutics as literary theory and method presented in the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism with further elaboration from several other texts. The central aim of the thesis is to illuminate the challenges inherent in the literary interpretive arts by investigating select philosophical and linguistic approaches to the study and practice of literary theory and criticism embodied within the canonical works of the Anthology. -

ION: Plato's Defense of Poetry Critical Introduction We

ION: Plato's defense of poetry Critical Introduction We occasionally use a word as a position marker. For example, the word 'Plato' is most often used to mark an anti-poetic position in the "old quarrel" between philosophy and poetry. Occasionally that marker is shifted slightly, but even in those cases it does not shift much. So, W.K.C. Guthrie in his magisterial History of Greek Philosophy1 can conclude [Plato] never flinched from the thesis that poets, unlike philosophers, wrote without knowledge and without regard to the moral effect of their poems, and that therefore they must either be banned or censored (Vol IV, 211). Generally, studies of individual dialogues take such markers as their interpretative horizon. So, Kenneth Dorter,2 who sees the importance of the Ion as "the only dialogue which discusses art in its own terms at all" (65) begins his article with the statement There is no question that Plato regarded art as a serious and dangerous rival to philosophy—this is a theme that remains constant from the very early Ion to the very late Laws (65). Even in those very rare instances where the marker is itself brought into question, as Julius Elias' Plato's Defence of Poetry3 attempts to do, the one dialogue in which Plato picks up poetry (rather than rhetoric) on its own account and not in an explicitly political or educational setting—the Ion—is overlooked entirely or given quite short shrift. Elias, after a two paragraph summary of the dialogue says "almost anybody could defend poetry better than Ion; we must look elsewhere for weightier arguments and worthier opponents" (6) and does not refer to the dialogue again in his book. -

The Rhetoric of Poetry Contests and Competition Marc Pietrzykowski

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 8-7-2007 Winning, Losing, and Changing the Rules: The Rhetoric of Poetry Contests and Competition Marc Pietrzykowski Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pietrzykowski, Marc, "Winning, Losing, and Changing the Rules: The Rhetoric of Poetry Contests and Competition." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/21 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Winning, Losing, and Changing the Rules: The Rhetoric of Poetry Contest and Competition by Marc Pietrzykowski Under the Direction of Dr. George Pullman ABSTRACT This dissertation attempts to trace the shifting relationship between the fields of Rhetoric and Poetry in Western culture by focusing on poetry contests and competitions during several different historical eras. In order to examine how the distinction between the two fields is contingent on a variety of local factors, this study makes use of research in contemporary cognitive neuroscience, -

Scholasticism, the Medieval Synthesis CVSP 202 General Lecture Tuesday, November 06, 2012 Encountering Aristotle in the Middle-Ages Hani Hassan [email protected]

Scholasticism, The Medieval Synthesis CVSP 202 General Lecture Tuesday, November 06, 2012 Encountering Aristotle in the middle-ages Hani Hassan [email protected] PART I – SCHOLASTIC PHILOSOPHY A. Re-discovering Aristotle & Co – c. 12th Century The Toledo school: translating Arabic & Hebrew philosophy and science as well as Arabic & Hebrew translations of Aristotle and commentaries on Aristotle (notably works of Ibn Rushd and Maimonides) From Toledo, through Provence, to… th Palermo, Sicily – 13 Century – Under the rule of Roger of Sicily (Norman ruler) th Faith and Reason united William of Moerbeke (Dutch cleric): greatest translator of the 13 by German painter Ludwig Seitz century, and (possibly) ‘colleague’ of Thomas Aquinas. (1844–1908) B. Greek Philosophy in the Christian monotheistic world: Boethius to scholasticism Boethius: (c. 475 – c. 526) philosopher, poet, politician – best known for his work Consolation of Philosophy, written as a dialogue between Boethius and 'Lady Philosophy', addressing issues ranging from the nature and essence of God, to evil, and ethics; translated Aristotle’s works on logic into Latin, and wrote commentaries on said works. John Scotus Eriugena (c. 815 – c. 877) Irish philosopher of the early monastic period; translated into Latin the works of pseudo-Dionysius, developed a Christian Neoplatonic world view. Anselm (c. 1033 – 1109) Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109; best known for his “ontological argument” for the existence of God in chapter two of the Proslogion (translated into English: Discourse on the Existence of God); referred to by many as one of the founders of scholasticism. Abelard (1079 – 1142) philosopher, theologian, poet, and musician; reportedly the first to use the term ‘theology’ in its modern sense; remembered as a tragic figure of romance due to his ‘infamous’ love affair with Heloise; wrote on metaphysics, logic, philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, ethics, and theology. -

Latin Averroes Translations of the First Half of the Thirteenth Century

D.N. Hasse 1 Latin Averroes Translations of the First Half of the Thirteenth Century Dag Nikolaus Hasse (Würzburg)1 Palermo is a particularly appropriate place for delivering a paper about Latin translations of Averroes in the first half of the thirteenth century. Michael Scot and William of Luna, two of the translators, were associated with the court of the Hohenstaufen in Sicily and Southern Italy. Michael Scot moved to Italy around 1220. He was coming from Toledo, where he had already translated at least two major works from Arabic: the astronomy of al-BitrÚºÍ and the 19 books on animals by Aristotle. In Italy, he dedicated the translation of Avicenna’s book on animals to Frederick II Hohenstaufen, and he mentions that two books of his own were commissioned by Frederick: the Liber introductorius and the commentary on the Sphere of Sacrobosco. He refers to himself as astrologus Frederici. His Averroes translation, however, the Long Commentary on De caelo, is dedicated to the French cleric Étienne de Provins, who had close ties to the papal court. It is important to remember that Michael Scot himself, the canon of the cathedral of Toledo, was not only associated with the Hohenstaufen, but also with the papal court.2 William of Luna, the other translator, was working apud Neapolim, in the area of Naples. It seems likely that William of Luna was associated to Manfred of Hohenstaufen, ruler of Sicily.3 Sicily therefore is a good place for an attempt to say something new about Michael Scot and William of Luna. In this artic le, I shall try to do this by studying particles: small words used by translators. -

9 a Hidden Source of the Prologue to the I-Ii of The

A HIDDEN SOURCE OF THE PROLOGUE TO THE I-II OF THE SUMMA THEOLOGIAE OF ST. THOMAS AQUINAS MARGHERITA MARIA ROSSI* – TEODORA ROSSI** Pontifical University St Thomas Aquinas, Rome ABSTRACT This article1 investigates a particular aspect of the well-known quotation that opens the Prologue of the Prima Secundae of the Summa Theologiae. For scholars of St. Thomas Aquinas and the Middle Ages, the history of the introduction and story of the translation of the quoted text from St. John Damascene is a matter of undisputed interest. In particular, the cu- rious addition to the Damascene quote, not found in the translations cir- culating at the time Aquinas wrote the Prologue, nor even in the work of other contemparies, presents itself as an enigma. Although the practice of citation in the Middle Ages included taking some liberties from the text itself, it should be noted that this does not mean that it was done without rules or reason. In fact, the citations were chosen and presented in such a way as to respond to the most pressing * Contact: [email protected] ** Contact: [email protected] 1. The authors are deeply indebted to Father Peter Marsalek, SOLT, for graciously volunteering to translate the article into English. Thanks to his Thomistic expertise, Father Marsalek has translated the nuances of a demanding centuries-old theological debate, one which involves Greek and Latin authors to whom St. Thomas Aquinas re- fers. Father Peter Marsalek’s linguistic mastery and his passionate commitment have managed to clarify the most crucial passages of the difficult Italian text. -

010 Nagy Epic.Pdf (258.2Kb)

Epic The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2009. Epic. In The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Literature, edited by Richard Eldridge, 19–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Published Version doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195182637.003.0002 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:15479860 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Epic Gregory Nagy [[This essay is an online version of an original printed version that appeared as Chapter 1 in The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Literature, ed. Richard Eldridge (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2009) 19-44. In this online version, the original page-numbers of the printed version are indicated within braces (“{” and “}”). For example, “{19|20}” indicates where p. 19 of the printed version ends and p. 20 begins.]] What is epic? For a definition, we must look to the origins of the term. The word epic comes from the ancient Greek noun epos. As we are about to see, epos refers to a literary genre that we understand as ‘epic’. But the question is, can we say that this word epic refers to the same genre as epos? The simple answer is: no. But the answer is complicated by the fact that there is no single understanding of the concept of a genre - let alone the concept of epic. -

Introduction to Hesiod

INTRODUCTION TO HESIOD unlike homer, whose identity as a poet is so obscure that it is sometimes proposed that he is a committee, Hesiod’s dis- tinctive voice in the Theogony (Th) and the Works and Days (WD) delivers to us the ‹rst “poetic self ” and depicts the ‹rst poetic career in western literature. He is afraid of sailing, hates his home- town (Askra), has a brother and a father, entered a poetry contest, and has (or re›ects) signi‹cant anxieties about women. Most of this information comes from the Works and Days, because the didactic genre exploits the ‹rst-person speaker’s authority. However, even in the Theogony the poet’s relation to the Muses has a personal edge that makes the invocation’s generic appeal Hesiod’s particular call. The view that Homer (that is, the poet conventionally known as the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey) was earlier than Hesiod has recently given way to some skepticism, but in any case the poems of both, in the form we have them written, date from between 750 and 600 BCE. Hesiod and Homer were paired in antiquity, as they are today, as the great epic poets of the Greek archaic era. To us their similarities seem few. For one thing, we have no sense of the organizing power of the dactylic hexameter, the meter in which Hesiod’s and Homer’s poems are composed and whose sound de‹ned epic, nor of the Ionian dialect that was the characteristic speech of archaic Greek epic. To modern stu- dents “epic” as a genre suggests something big, usually historic, sometimes overblown; epic can ‹t the grand scope of Homer, but not Hesiod’s comparative brevity (one book of the Iliad can be as long as the whole Works and Days, and the Theogony only exceeds it by two hundred lines). -

Scholasticism, the Medieval Synthesis CVSP 202 General Lecture Monday, March 23, 2015 Encountering Aristotle in the Middle-Ages Hani Hassan [email protected]

Scholasticism, The Medieval Synthesis CVSP 202 General Lecture Monday, March 23, 2015 Encountering Aristotle in the middle-ages Hani Hassan [email protected] PART I – SCHOLASTIC PHILOSOPHY SCHOLASTIC: “from Middle French scholastique, from Latin scholasticus "learned," from Greek skholastikos "studious, learned"” 1 Came to be associated with the ‘teachers’ and churchmen in European Universities whose work was generally rooted in Aristotle and the Church Fathers. A. Re-discovering Aristotle & Co – c. 12th Century The Toledo school: translating Arabic & Hebrew philosophy and science as well as Arabic & Hebrew translations of Aristotle and commentaries on Aristotle (notably works of Ibn Rushd and Maimonides) Faith and Reason united From Toledo, through Provence, to… th by German painter Ludwig Seitz Palermo, Sicily – 13 Century – Under the rule of Roger of Sicily (Norman (1844–1908) ruler) th William of Moerbeke (Dutch cleric): greatest translator of the 13 century, and (possibly) ‘colleague’ of Thomas Aquinas. B. Greek Philosophy in the Christian monotheistic world: Boethius to scholasticism Boethius: (c. 475 – c. 526) philosopher, poet, politician – best known for his work Consolation of Philosophy, written as a dialogue between Boethius and 'Lady Philosophy', addressing issues ranging from the nature and essence of God, to evil, and ethics; translated Aristotle’s works on logic into Latin, and wrote commentaries on said works. John Scotus Eriugena (c. 815 – c. 877) Irish philosopher of the early monastic period; translated into Latin the works of pseudo-Dionysius, developed a Christian Neoplatonic world view. Anselm (c. 1033 – 1109) Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109; best known for his “ontological argument” for the existence of God in chapter two of the Proslogion (translated into English: Discourse on the Existence of God); referred to by many as one of the founders of scholasticism. -

The Earliest Translations of Aristotle's Politics and The

ECKART SCHÜTRUMPF THE EARLIEST TRANSLATIONS OF ARISTOTle’S POLITICS AND THE CREATION OF POLITICAL TERMINOLOGY 8 MORPHOMATA LECTURES COLOGNE MORPHOMATA LECTURES COLOGNE 8 HERAUSGEGEBEN VON GÜNTER BLAMBERGER UND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG ECKART SCHÜTRUMPF THE EARLIEST TRANSLATIONS OF ARISTOTLe’s POLITICS AND THE CREATION OF POLITICAL TERMINOLOGY WILHELM FINK unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK0905. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt der Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autoren. Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National biblio grafie; detaillierte Daten sind im Internet über www.dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Alle Rechte, auch die des auszugweisen Nachdrucks, der fotomechanischen Wieder gabe und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Dies betrifft auch die Vervielfälti gung und Übertragung einzelner Textabschnitte, Zeichnungen oder Bilder durch alle Verfahren wie Speicherung und Übertragung auf Papier, Transparente, Filme, Bänder, Platten und andere Medien, soweit es nicht § 53 und 54 UrhG ausdrücklich gestatten. © 2014 Wilhelm Fink, Paderborn Wilhelm Fink GmbH & Co. VerlagsKG, Jühenplatz 1, D33098 Paderborn Internet: www.fink.de Lektorat: Sidonie Kellerer, Thierry Greub Gestaltung und Satz: Kathrin Roussel, Sichtvermerk Printed in Germany Herstellung: Ferdinand Schöningh GmbH & Co. KG, Paderborn ISBN 978-3-7705-5685-4 CONTENT 1. The earliest Latin translations of Aristotle— William of Moerbeke 9 2. Nicole Oresme 25 3. Leonardo Bruni’s principles of translation 28 4. Bruni’s translation of Aristotle’s Politics 33 5. The political terminology in Bruni’s translation— a new Humanist concept of res publica? 39 6. The controversy over Bruni’s translation— contemporary and modern 65 Appendix 77 Bibliography 78 This study goes back ultimately to a response I gave on two pa pers presented on “Translating Aristotle’s Politics in Medieval and Renaissance Europe” at the “International Conference on Translation. -

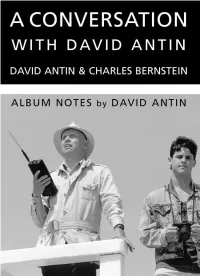

A Conversation with David Antin

A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID ANTIN DAVID ANTIN & CHARLES BERNSTEIN ALBUM NOTES by DAVID ANTIN GRANARY BOOKS NEW YORK CITY 2002 © 2002 David Antin, Charles Bernstein & Granary Books, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced without express written permission of the author or publisher. A portion of this conversation was published in The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Vol. XXI No. 1, Spring 2001. Printed and bound in the United States of America in an edition of 1000 copies of which 26 are lettered and signed. Cover and Book Design: Julie Harrison Cover photo: Phel Steinmetz Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Antin, David. A conversation with David Antin / David Antin and Charles Bernstein ; and album notes, David Antin. p. cm. ISBN 1-887123-55-5 1. Antin, David--Interviews. 2. Poets, American--20th century--Interviews. I. Bernstein, Charles, 1950- II. Title. PS3551.N75 Z465 2002 811'.54--dc21 2002001192 Granary Books, Inc. 307 Seventh Ave. Suite 1401 New York, NY 10001 USA www.granarybooks.com Distributed to the trade by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers 155 Avenue of the Americas, Second Floor New York, NY 10013-1507 Orders: (800) 338-BOOK • Tel.: (212) 627-1999 • Fax: (212) 627-9484 Also available from Small Press Distribution 1341 Seventh Street Berkeley, CA 94710 Orders: (800) 869-7553 • Tel.: (510) 524-1668 • Fax: (510) 524-0582 www.spdbooks.org David Antin and Charles Bernstein Charles Bernstein: In 1999, I had the opportunity to tour Brooklyn Technical High School with my daughter Emma, who was just going into ninth grade. -

Anatomy of Criticism with a New Foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY of CRITICISM

Anatomy of Criticism With a new foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Four Essays Anatomy of Criticism FOUR ESSAYS With a Foreword by Harold Bloom NORTHROP FRYE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY Copyright © 1957, by Princeton University Press All Rights Reserved L.C. Card No. 56-8380 ISBN 0-691-06999-9 (paperback edn.) ISBN 0-691-06004-5 (hardcover edn.) Fifteenth printing, with a new Foreword, 2000 Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, and the Class of 1932 Lectureship. FIRST PRINCETON PAPERBACK Edition, 1971 Third printing, 1973 Tenth printing, 1990 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) {Permanence of Paper) www.pup.princeton.edu 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 Printed in the United States of America HELENAE UXORI Foreword NORTHROP FRYE IN RETROSPECT The publication of Northrop Frye's Notebooks troubled some of his old admirers, myself included. One unfortunate passage gave us Frye's affirmation that he alone, of all modern critics, possessed genius. I think of Kenneth Burke and of William Empson; were they less gifted than Frye? Or were George Wilson Knight or Ernst Robert Curtius less original and creative than the Canadian master? And yet I share Frye's sympathy for what our current "cultural" polemicists dismiss as the "romantic ideology of genius." In that supposed ideology, there is a transcendental realm, but we are alienated from it.