Def Leppard's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

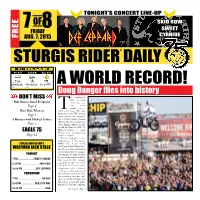

A World Record!

TONight’s CONCERT LINE-UP OF SKID ROW EE 7 8 SWEET FRIDAY CYANIDE FR AUG. 7, 2015 ® STURGIS RIDER DAILY Fri 8/7 Sat 8/8 Sun 8/9 A WORLD RecORD! Doug Danger flies into history he undisputed DON’t Miss king of stunt Bob Hansen Award Recipients men? Sure, cer- Page 4 tain names might come to Rat’s Hole Winners mind at that phrase. But since Tyesterday, at 6:03 PM, the only Page 5 name people are mention- 5 Minutes with Michael Lichter ing is Doug Danger. Because that was the time on the clock Page 3 when Danger jumped 22 cars aboard Evel Knievel’s XR-750 Harley-Davidson, a stunt EAGLE 75 Knievel once attempted but Page 12 failed to complete. The feat took place in the amphitheater at the Sturgis STURGIS BUFFALo Chip’s Buffalo Chip as part of the Evel Knievel Thrill Show. Dan- WOLFMAN JACK STAGE ger, who has been performing motorcycle jumps for decades, TONIGHT was inspired by Knievel when he was young and got to know 7 PM ..................SWEET CYANIDE him later in life. Danger 8:30 PM .....................SKID ROW regarded this stunt not as way to best his hero but as a favor, 10:30 PM ...............DEF LEPPARD completing a task for a friend. Danger is fully cognizant of TOMORROW the potential peril of his cho- sen profession and he’s real- 7 PM ............................ NICNOS istic; he knows firsthand the flip side of a successful jump. 8:30 PM ............... ADELITAS WAY But he felt solid and confident 10:30 PM ..........................WAR Continued on Page 2 PAGE 2 STURGIS RIDER DAILY FRIDAY, AUG. -

November 1983

VOL. 7, NO. 11 CONTENTS Cover Photo by Lewis Lee FEATURES PHIL COLLINS Don't let Phil Collins' recent success as a singer fool you—he wants everyone to know that he's still as interested as ever in being a drummer. Here, he discusses the percussive side of his life, including his involvement with Genesis, his work with Robert Plant, and his dual drumming with Chester Thompson. by Susan Alexander 8 NDUGU LEON CHANCLER As a drummer, Ndugu has worked with such artists and groups as Herbie Hancock, Michael Jackson, and Weather Report. As a producer, his credits include Santana, Flora Purim, and George Duke. As articulate as he is talented, Ndugu describes his life, his drumming, and his musical philosophies. 14 by Robin Tolleson INSIDE SABIAN by Chip Stern 18 JOE LABARBERA Joe LaBarbera is a versatile drummer whose career spans a broad spectrum of experience ranging from performing with pianist Bill Evans to most recently appearing with Tony Bennett. In this interview, LaBarbera discusses his early life as a member of a musical family and the influences that have made him a "lyrical" drummer. This accomplished musician also describes the personal standards that have allowed him to maintain a stable life-style while pursuing a career as a jazz musician. 24 by Katherine Alleyne & Judith Sullivan Mclntosh STRICTLY TECHNIQUE UP AND COMING COLUMNS Double Paradiddles Around the Def Leppard's Rick Allen Drumset 56 EDUCATION by Philip Bashe by Stanley Ellis 102 ON THE MOVE ROCK PERSPECTIVES LISTENER'S GUIDE Thunder Child 60 A Beat Study by Paul T. -

Def Leppard – 02

DEF LEPPARD – 02. Juli 2019 – Berlin – Zitadelle Spandau – Support: EUROPE – JOHN DIVA and the Rockets of Love – Text und Fotos: Holger Ott Im Zeichen des Retro rufen die Bands der guten alten 80er Jahre und die Fans pilgern in die Zitadelle Spandau von Berlin. Das alte Gemäuer ist beliebt, gibt es neben sehr guter Akustik auch von allen Plätzen eine hervorragende Sicht auf die schöne große Bühne. Das Wetter spielt heute auch mit. Weder zu heiß noch zu kalt und bei einem kleinen Lüftchen lässt es sich einige Stunden aushalten. Dieses Stehvermögen braucht das Publikum, denn mit drei Bands stehen, abgesehen von den Umbaupausen, geschlagene drei Stunden Musik auf dem Programm Eröffnet wird der Abend von einer, mir bis dato, unbekannten Band. JOHN DIVA mit seinen 'Rockets of Love' geben sich die Ehre und präsentieren in dreißig Minuten eine beeindruckende musikalische und optische Darbietung unter dem Motto: „Mama said, Rock is dead". Frontman JOHN DIVA und seine Mannen turnen in extravagantem Outfit über die Bühne. Schön grell und bunt darf es sein und sieht man dazu DIVAS passenden Hüftschwung, weiß der Fan sofort, dass es hier nur um Sex, Drugs and Rock 'n' Roll geht. Ohne Zweifel, die Truppe ist gut und rockt auch richtig fett ab. Also, im Auge behalten. Ein gelungener Einstand in den heutigen Abend. Zu EUROPE muss man nicht viel sagen. JOEY TEMPEST ist in top Form und schmettert seine bekanntesten Songs in die Menge. Das Gedränge vor der Bühne wird größer und der Hype wächst mit jedem Song ihrer einstündigen Show. Leider fällt durch die Supporterstellung einiges unter den Tisch, aber Hits wie „Carrie", „Superstitius" und natürlich das abschließende "The Final Countdown" reißen wieder alles heraus. -

1Ssues• May Stall Pact for Faculty

In Sports I" Section 2 ·An Associated Collegiate Press Four-Star All-American Newspaper Coles soars in The Boss is NCAA slam back with two dunk contest new albums page 85 page 81 Economic 1ssues• may stall pact for faculty By Doug Donovan ltdmindltllitie news Editor He said, she said. So went the latest round of contract negotiations between the faculty and the administration. The faculty's contract negotiating team contends that administrative bargaining tactics have the potential to stall the talks and delay the signing of a new contract. But the administration says the negotiations are moving at a normal pace. Robert Carroll, president of the l~cal chapter of the Association of American University Professors (AAUP), said he was disappointed with the March 27 talk~ because the administrative bargaining team came to the session stating it was "not prepared to discuss economic issues." • "It was an amicable session and a number of issues were discussed at length," said Carroll, a professor in the plant and soil science depanment. "But very little progress was made." However, Maxine R. Colm, leader of the administrative b~rgaining team, said an agreement was reached with the AAUP to THE REVIEW / Lori Barbag pursue non-economic issues of the proposed A delegation from the university was among the 500,000 who attended Sunday's rally for what supporters called "reproductive freedom." contract before economic issues. "We agreed to discuss non-economic issues first and we did precisely that," said Colm, who also serves as the university's vice president for Employee Relations. ' . Colm said that "not prepared" was a Half million rally for abortion rights common phrase used by negotiating parties when they are not going to discuss a certain topic. -

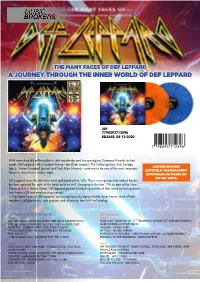

A Journey Through the Inner World of Def Leppard

THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD A JOURNEY THROUGH THE INNER WORLD OF DEF LEPPARD 2LP 7798093712896 RELEASE: 04-12-2020 With more than 65 million albums sold worldwide and two prestigious Diamond Awards to their credit, Def Leppard with its current line-up –Joe Elliott (vocals), Phil Collen (guitar), Rick Savage LIMITED EDITION (bass), Vivian Campbell (guitar) and Rick Allen (drums)— continue to be one of the most important GATEFOLD TRANSPARENT forces in rock music.n many ways, ORANGE/BLUE MARBLED 180 GR. VINYL Def Leppard were the definitive hard rock band of the ‘80s. There were groups that rocked harder, but few captured the spirit of the times quite as well. Emerging in the late ‘70s as part of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, Def Leppard gained a following outside of that scene by toning down their heavy riffs and emphasizing melody. In The Many Faces of Def Leppard, we are going to dig deep into the lesser known work of their members, collaborations, side projects and of course, their hit-filled catalog. LP1 - THE MANY FACES OF DEF LEPPARD LP2 - THE SONGS Side A Side A ALL JOIN HANDS - ROADHOUSE FEAT. PETE WILLIS & FRANK NOON POUR SOME SUGAR ON ME - LEE THOMPSON, JOHNNY DEE, RICHARD KENDRICK, I WILL BE THERE - GOMAGOG FEAT. PETE WILLIS & JANICK GERS MARKO PUKKILA & HOWIE SIMON DOIN’ FINE - CARMINE APPICE FEAT. VIVIAN CAMPBELL HYSTERIA - DANIEL FLORES ON A LONELY ROAD - THE FROG & THE RICK VITO BAND LET IT GO - WICKED GARDEN FEAT. JOE ELLIOTT ROCK ROCK TIL YOU DROP - CHRIS POLAND, JOE VIERS & RICHARD KENDRICK OVER MY DEAD BODY - MAN RAZE FEAT. -

Def Leppard “Hysteria” By: Kyle Harman

Def Leppard “Hysteria” By: Kyle Harman Hysteria would be a fitting name for the album thought Def Leppard drummer Rick Allen, following his 1984 injury from a horrific car accident that resulted in the loss of his left arm, Hysteria was the perfect title to describe the worldwide media coverage that followed the band between the years of 1984 and 1987. The album was the last to feature the late Steve Clark and his role of lead guitarist due to an overdose in the year of 1992. In the very prime years of glam metal in the late 80’s at the dawn of grunge genre about to begin, Def Leppard delivered the bands bestselling album to date with selling 25 million copies worldwide and 12 million in the US alone. The three year recording process of Hysteria was painstaking with the accident of drummer Rick Allen, and with producers coming and going left the band with the perfect example of sometimes patience truly does pay off. A unique recording process took place where each member recorded their own recordings at separate times, allowing each member to focus on their own performance on the album. The original intent of the album was to be a rock version of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, with the desire of having every song off the album as a possible hit single. The end result of the album was impressive to say the least with 7 singles released off the single album alone. The album recording sessions were painstaking at times, “Animal” consisted of 2 and a half years to produce its final product, where “Pour Some Sugar On Me” was finished within two weeks. -

Please Read Before Loading Card Into

Top 50 Drummers V.I Expansion Pack a sound enhancing expansion pack for the Roland TD-20 Drum Module Owner’s Manual i End User License Agreement (EULA) This is a legal agreement ("this Agreement") between you and V Expressions LTD., ("V Expressions LTD."). This Agreement pertains to your use of the V Expressions LTD. expansion programming, documentation and updates which are provided to you by V Expressions LTD (collectively, the "Product"). By purchasing a V Expressions LTD. Product, you are consenting to the terms of this Agreement. This Agreement grants you a personal, exclusive, non-transferable, non-sub licensable right to use one copy of the V Expressions LTD. Product for your own personal use on a single computer and/or compatible drum module. V Expressions LTD. reserves all rights in the Product not expressly granted herein, including ownership and proprietary rights. This software may not, in whole or in any part, be copied, reproduced, resold, transmitted, translated (into any language, natural or computer), reduced to any electronic medium or machine readable format, or by any other form or means without prior consent, in writing, from V Expressions LTD. License Restrictions: You may not reproduce or distribute the Product. You may not copy the Product to any media, server or location for reproduction or distribution. You may not reverse engineer, de-compile or disassemble the Product or otherwise attempt to derive the source code for the Product, or without limitation, redistribute, sublicense, or otherwise transfer rights in the Product. This Product may not be rented, lent or leased. The restrictions contained herein apply equally to any updates that may be provided to you by V Expressions LTD. -

The Great One

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU The Utah Statesman Students 2-10-2015 The Utah Statesman, February 10, 2015 Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/newspapers Recommended Citation Utah State University, "The Utah Statesman, February 10, 2015" (2015). The Utah Statesman. 224. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/newspapers/224 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Students at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Utah Statesman by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sports/News the utah Tuesday, Feb. 10, 2015 • www.usustatesman.com • (435)-797-1742 • Free single copy The Great One A look back at the impact Wayne Estes had on Utah State University 50 years after his death 4By Kalen Taylor high of 52 set earlier that season. A ago ended Estes’ life, his legacy and center on the 1965 team and the Estes’ junior season in 1963-64 sports editor downed power line grazed the top impact at the university continues first player to meet Estes in Logan. brought more of the same — only of the 6-foot-6-inch Estes’s head, to be felt to this day. “He was a great talent. As a player better. He shot the same percent- “Wayne Estes is dead, and sending electricity jolting through As a basketball player, they sim- he was never selfish. He was always age, upped his rebounds to 13 per Utah State will never be the his body. ply didn’t come any better. -

Adrenalized : Life, Def Leppard and Beyond Kindle

ADRENALIZED : LIFE, DEF LEPPARD AND BEYOND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Philip Collen | 256 pages | 19 May 2016 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780552170451 | English | London, United Kingdom Adrenalized : Life, Def Leppard and Beyond PDF Book It amazes me no one will do that! It may not be everyone's cup of tea, but I, for one, found his take on fame and fortune refreshing. Could Phil Collen become your personal coach then? Harry Crisswell July 18, at pm Reply. I thought the guys were gonna hate it, but I showed it to them anyway — and they really liked it. Wow, these are beautiful! That's what happened to Rep. You can get away with a lot less, just by tweaking it here and there. I'm a huge Def Leppard fan. Leading with a foot-tapping bass beat, "Man Enough" has a jangly rhythm track that uses guitars sparingly. There is beauty in all of it. I lost 6 pounds in a week, and I wasn't actually trying to lose weight. They convey genuine strain and regret about a lost love, alongside a serene acoustic guitar. Sammy Helen! I knew that Collen started in a band named girl with Phil Lewis who went on the L. Def Leppard On Through the Night. Still, the band received a good amount of grief for releasing something so polished in a time when alternative bands were beginning to invade the airwaves. I also didn't appreciate that he blames this evil on religion, greed, blah blah blah, all while admitting his profession is part of the problem. -

LN PR Template

KISS & DEF LEPPARD - THE WORLD’S BIGGEST ROCK BANDS SET TO TOUR THIS SUMMER - Tickets On Sale Starting Friday, March 21 Through Live Nation Mobile App and at LiveNation.com - LOS ANGELES – March 17, 2014 – This summer two of the world's greatest rock bands, KISS and DEF LEPPARD, are set to deliver a massive tour dedicated to fans who wanna rock and roll all night! These two legendary rock bands spanning two continents announced today that they will launch the tour as KISS celebrates their 40th year in music. The summer's biggest hit-fueled rock tour, promoted exclusively by Live Nation, will storm through 40-plus cities throughout North America kicking-off on Monday, June 23 in West Valley City, UT at the USANA Amphitheater. Tickets go on sale starting on Friday, March 21 through the Live Nation mobile app and at www.livenation.com. KISS and Def Leppard jointly decided to support our heroes and honor their dedicated fans in the armed services by partnering with numerous military organizations for the tour. Partnerships will include the USO, Hiring Our Heroes, Project Resiliency/The Raven Drum Foundation, August Warrior Project and the Wounded Warrior Project. All military personnel will be given exclusive access to discounted tickets for the tour with their own pre-sale through Military.com/Monster.com while also participating in the tour launch announcement featuring a live streamed Q&A with band members from KISS and Def Leppard in Los Angeles, California at the House Of Blues on Monday, March 17. Military charities will receive a portion of ticket sales with the money raised being split amongst all the non-profit organizations participating with the summer tour. -

M. Edia Board Upheld

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives Fall 11-6-1992 The Parthenon, November 6, 1992 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, November 6, 1992" (1992). The Parthenon. 3087. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/3087 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. November· 6, 1992 THURSDAY Light rain; high in mid-40s M.edia board upheld Bu_t judge says Gilley's procedure may not be wisest By Cheryl J. WIison creation of the Student Media Board cause it doesn't control policy, it "in and Tim D. Hardiman without first consulting faculty, "may creases the spectrum of people who Reporters not have been the wisest thing to do." influence policy." Bruce Walker, attorney for the Board Cummings decided there was no at A Cabell County Circuit Court judge of Trustees, asked Cummings to deny tempt to control content in The Parthe Thursday denied a journalism testimony ofJensen's subpoenaed wit non. professor's request for a temporary in nesses because it was a "fishing expedi After the ruling Jensen said he was junction against President J. Wade tion." But Cummings denied the re uncertain ifhe would take the case fur Gilley's student media board. quest. ther, and doubted it would harm his Dwight Jensen, associate professor During the two-hour hearing, testi chance of getting tenure.