Gagosian Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gagosian Gallery

Artsy April 2, 2019 GAGOSIAN How Takashi Murakami Got His Start as an Artist Scott Indrisek “At the studio I rented for $80 a month on Lorimer Street in Brooklyn, uncertain whether I would have anything to eat the next day.” © Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Courtesy of Gagosian. In the second installment of a new series, we continue to shine a light on the tumultuous early days of artists who have since become household names. Takashi Murakami, 57, may now be an international art star and a cultural icon, but he was once a disgruntled student, bored with his conservative schooling and dreaming of better things. Indeed, when he was just starting out, Murakami claimed no special status as an artist. “I was never particularly talented at drawing or painting,” he said; hard work, practice, and determination would sharpen those skills. He had his first solo show in 1989, at Tokyo’s Ginza Surugadai Gallery, and began traveling from his native Japan to New York City around that time. Murakami always thought of New York as one of the art world’s vital centers, and he was willing to struggle in order to absorb what it had to offer. He recalled once renting a studio on Lorimer Street in Brooklyn for a mere $80 a month (“uncertain whether I would have anything to eat the next day,” he added). In 1994, he landed a residency in the prestigious PS1 International Studio Program. These early experiences helped shape Murakami’s unique artistic vision. The hyperconfident artist would eventually become a global brand, his manga-inspired creations taking over the world—one wild sculpture and painting at a time. -

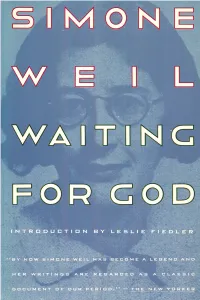

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Damien Hirst Visual Candy and Natural History

G A G O S I A N 7 February 2018 DAMIEN HIRST VISUAL CANDY AND NATURAL HISTORY EXTENDED! Through Saturday, March 3, 2018 7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street Central, Hong Kong I had my stomach pumped as a child because I ate pills thinking they were sweets […] I can’t understand why some people believe completely in medicine and not in art, without questioning either. —Damien Hirst Gagosian is pleased to present “Visual Candy and Natural History,” a selection of paintings and sculptures by Damien Hirst from the early- to mid-1990s. The exhibition coincides with Hirst’s most ambitious and complex project to date, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,” on view at Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice until December 3. Since emerging onto the international art scene in the late 1980s as the protagonist of a generation of British artists, Hirst has created installations, sculptures, paintings and drawings that examine the complex relationships between art, beauty, religion, science, life and death. Through series as diverse as the ‘Spot Paintings’, ‘Medicine Cabinets’, ‘Natural History’ and butterfly ‘Kaleidoscope Paintings,’ he has investigated and challenged contemporary belief systems, tracing the uncertainties that lie at the heart of human experience. This exhibition juxtaposes the joyful, colorful abstractions of his ‘Visual Candy’ paintings with the clinical forms of his ‘Natural History’ sculptures. Page 1 of 3 The ‘Visual Candy’ paintings allude to movements including Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, while the ‘Natural History’ sculptures—glass tanks containing biological specimens preserved in formaldehyde—reflect the visceral realities of scientific investigation through minimalist design. -

THBT Social Disgust Is Legitimate Grounds for Restriction of Artistic Expression

Published on idebate.org (http://idebate.org) Home > THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression THBT social disgust is legitimate grounds for restriction of artistic expression The history of art is full of pieces which, at various points in time, have caused controversy, or sparked social disgust. The works most likely to provoke disgust are those that break taboos surrounding death, religion and sexual norms. Often, the debate around whether a piece is too ‘disgusting’ is interwoven with debate about whether that piece actually constitutes a work of art: people seem more willing to accept taboo-breaking pieces if they are within a clearly ‘artistic’ context (compare, for example, reactions to Michelangelo’s David with reactions to nudity elsewhere in society). As a consequence, the debate on the acceptability of shocking pieces has been tied up, at least in recent times, with the debate surrounding the acceptability of ‘conceptual art’ as art at all. Conceptual art1 is that which places an idea or concept (rather than visual effect) at the centre of the work. Marchel Duchamp is ordinarily considered to have begun the march towards acceptance of conceptual art, with his most famous piece, Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt”. It is popularly associated with the Turner Prize and the Young British Artists. This debate has a degree of scope with regards to the extent of the restriction of artistic expression that might be being considered here. Possible restrictions include: limiting display of some pieces of art to private collections only; withdrawing public funding (e.g. -

Gagosian Gallery

Financial Times January 20, 2020 GAGOSIAN Living with Damien Hirst and friends Robert Tibbles was an early collector of the Young British Artists — now he is preparing to sell many of his acquisitions Melanie Gerlis Caption (TNR 9 Italicized) Everyone likes to say that they discovered an artist before they were famous, but in the case of the London bond salesman Robert Tibbles, the claim is true. Back in the 1980s, the late art dealer Karsten Schubert introduced Tibbles to the work of an art student called Damien Hirst. Alongside Charles Saatchi, Tibbles then became one of the now-superstar artist’s first buyers. So began an intense, 15-year collecting spree, mostly of works by Hirst and other Young British Artists. These now dominate Tibbles’s Victorian ground-floor flat in London’s leafy Kensington, where an early Hirst spot painting, “Antipyrylazo III” (1994), has loomed almost too large over the living room fireplace since Tibbles bought it in the year it was made. Hanging nearby is another early purchase — Hirst’s degree-show medicine cabinet “Bodies” (1989) — a work that demonstrates Tibbles’s aptitude for picking the right time in the art market as well as the debt markets. He bought the cabinet for £600 (again, in the year it was made) and now, as Tibbles prepares to sell much of his YBA collection at auction at Phillips in London, the cabinet is valued between £1.2m and £1.8m. “There’s no question that the medicine cabinet and other works were not liked or understood by many of my friends. -

Gagosian Gallery

Artforum January, 2000 GAGOSIAN 1999 Carnegie International Carnegie Museum of Art Katy Siegel When you walk into the lobby of the Carnegie Museum, the program of this year’s International announces itself in microcosm. There in front of you is atmospheric video projection (Diana Thater), a deadpan disquisition on the nature of representation (Gregor Schneider’s replication of his home), a labor-intensive, intricate installation (Suchan Kinoshita), a bluntly phenomenological sculpture (Olafur Eliasson), and flat, icy painting (Alex Katz). Undoubtedly the best part of the show, the lobby is also an archi-tectural site of hesitation, a threshold. Here the installation encapsulates the exhi-bition’s sense of historical suspen-sion, another kind of hesitation. Ours is a time not of endings but of pause. My favorite work, viewed through the museum’s huge glass wall, was the Eliasson, a fountain of steam wafting vertically from an expanse of water on a platform through which trees also rise up. It’s a heart-throbbing romantic landscape. Romantic, but not naive: The work plays on the tradition of the courtyard fountain, and the steam is piped from the museum’s heating system. Combining the natural and the industrial in a way peculiarly appro-priate to Pittsburgh on a quiet Sunday morning in early autumn, it echoed two billows of steam (or, more queasily, smoke?) off in the distance. When blunt physical fact achieves this kind of lyricism, it is something to see. Upstairs in the galleries, Ernesto Neto’s Nude Plasmic, 1999, relies as well on the phenomenology of simple form, but the Brazilian artist avoids Eliasson’s picturesque imagery. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Anish Kapoor Biography Born in 1954, Mumbai, India. Lives and works in London, England. Education: 1973–1977 Hornsey College of Art, London, England. 1977–1978 Chelsea School of Art, London, England. Solo Exhibitions: 2016 Anish Kapoor. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. Anish Kapoor: Today You Will Be In Paradise. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico. 2015 Descension. Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Kapoor Versailles. Gardens at the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, Brussels, Belgium. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Prints from the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR. Anish Kapoor chez Le Corbusier. Couvent de La Tourette, Eveux, France. Anish Kapoor: My Red Homeland. Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, Moscow, Russia. 2013 Anish Kapoor in Instanbul. Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. Anish Kapoor Retrospective. Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany 2012 Anish Kapoor. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Leeum – Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea. Anish Kapoor, Solo Exhibition. PinchukArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Flashback: Anish Kapoor. Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England. Anish Kapoor. De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands. 2011 Anish Kapoor: Turning the Wold Upside Down. Kensington Gardens, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Flashback. Nottingham Castle Museum, Nottingham, England. -

The Theory and Practice of Visual Arts Marketing

The Tension Between Artistic and Market Orientation in Visual Art Dr Ian Fillis Department of Marketing University of Stirling Stirling Scotland FK9 4LA Email: [email protected] Introduction For centuries, artists have existed in a world which has been shaped in part by their own attitudes towards art but which also co-exists within the confines of a market structure. Many artists have thrived under the conventional notion of a market with its origins in economics and supply and demand, while others have created a market for their work through their own entrepreneurial endeavours. This chapter will explore the options open to the visual artist and examine how existing marketing theory often fails to explain how and why the artist develops an individualistic form of marketing where the self and the artwork are just as important as the audience and the customer. It builds on previous work which examines the theory and practice of visual arts marketing, noting that there has been little account taken of the philosophical clashes of art for art’s sake versus business sake (Fillis 2004a). Market orientation has received a large amount of attention in the marketing literature but product centred marketing has largely been ignored. Visual art has long been a domain where product and artist centred marketing have been practiced successfully and yet relatively little has been written about its critical importance to arts marketing theory. The merits and implications of being prepared to ignore market demand and customer wishes are considered here. 1 Slater (2007) carries out an investigation into understanding the motivations of visitors to galleries and concludes that, rather than focusing on personal and social factors alone, recognition of the role of psychological factors such as beliefs, values and motivations is also important. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Alexander Calder Biography Born in 1898, Lawnton, PA. Died in 1976, New York, NY. Education: 1926 Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, France. 1923–25 Art Students League, New York, NY. 1919 B.S., Mechanical Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ. Solo Exhibitions: 2015 Alexander Calder: Imagining the Universe. Sotheby’s S|2, Hong Kong. Calder: Lightness. Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Saint Louis, MO. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico. Alexander Calder: Multum in Parvo. Dominique Levy, New York, NY. Alexander Calder: Primary Motions. Dominique Levy, London, England. 2014 Alexander Calder. Fondation Beyeler, Basel. Switzerland. Alexander Calder: Gouaches. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. Alexander Calder: Gouaches. Gagosian Gallery, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, NY. Alexander Calder in the Rijksmuseum Summer Sculpture Garden. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. 2013 Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA. 2011 Alexander Calder. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. 2010 Alexander Calder. Gagosian Gallery, W. 21st Street, New York, NY. 2009 Monumental Sculpture. Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. 2005 Monumental Sculpture. Gagosian Gallery, W. 24th Street, New York, NY. Alexander Calder 60’s-70’s. GióMarconi, Milan, Italy. Calder: The Forties. Thomas Dane, London, England. 2004 Calder/Miró. Foundation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland. Traveled to: Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. (through 2005). Calder: Sculpture and Works on Paper. Elin Eagles-Smith Gallery, San Francisco, CA. 590 Madison Avenue, New York, NY. 2003 Calder. Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Calder: Gravity and Grace. -

Gagosian Gallery

The Brooklyn Rail June 5, 2018 GAGOSIAN Jenny Saville: Ancestors Jason Rosenfeld Jenny Saville, Byzantium, 2018. © Jenny Saville. Photo: by Mike Bruce. Courtesy Gagosian. The athleticism of Jenny Saville’s brushwork and draughtsmanship has been the hallmark of her work since her earliest exhibition in New York, at Gagosian's Wooster Street incarnation in 1999. She was then associated with Damien Hirst's band of Young British Artists, riding the Cool Britannia wave and establishing London as a prime destination for contemporary art for the first time since Victoria was queen. The elegance of Saville’s facture, the swirling and energetic pace of her drawing, made her inheritor of a tradition of gestural, bravura painting going back to Titian, Rubens, and Velázquez, and as reworked by John Everett Millais and Édouard Manet, and finally perfected by John Singer Sargent in the late-nineteenth century. This was then reprised and critiqued in the abstracted figuration of de Kooning and the visceral reconstitution of form of Lucien Freud in the post-war era. All those gesticulative men. If you were open to being energized by the pleasure of agilely pushed paint in the service of a kind of post-academic, post-modern, post-minimal realism, then Saville delivered, and her edgy subject matter paralleled a wave of artistic interest in the body, the self, the gaze, and the abject. By a woman. On a huge scale. In her second New York show, Migrants, the sight of Suspension (2002 – 03), featuring a headless pig sprawled on its side across almost fifteen feet of canvas and hung just off the ground in Gagsosian’s Chelsea digs at 24th Street in the spring of 2003 was memorable and remarkable. -

'Rachel Whiteread' Review: Where Memories Dwell

The Wall Street Journal October 2, 2018 GAGOSIAN ‘Rachel Whiteread’ Review: Where Memories Dwell The British sculptor draws on her formative experiences to create often-monumental works. Eric Gibson Rachel Whiteread’s ‘Ghost’ (1990) PHOTO: GLENSTONE FOUNDATION ‘Greatest living British artist” is among the most abused accolades in art criticism. The one person who deserves it is sculptor Rachel Whiteread, now the subject of a retrospective at the National Gallery of Art. “Rachel Whiteread,” which travels to the Saint Louis Art Museum after Washington, was jointly organized by the Gallery’s Molly Donovan and Ann Gallagher of Tate Britain, where it began its international tour last fall. It features some 100 sculptures and drawings. The list includes “Closet” (1988), a plaster cast of the interior space of a wardrobe wrapped in black felt to evoke the artist’s childhood habit of hiding in closets, and the 1995 model for her acclaimed “Holocaust Memorial” (2000) in Vienna’s Judenplatz. Generationally, Ms. Whiteread (b. 1963) is one of the Young British Artists, seen here in the notorious “Sensation” exhibition in 1999. Temperamentally, however, she couldn’t be more different from that group, lacking for example the drive-by irony of a Damien Hirst. Ms. Whiteread is old school: Her art expresses something personal and deeply felt. Rachel Whiteread’s ‘Untitled (Domestic)’ (2002) PHOTO: RACHEL WHITEREAD/GAGOSIAN, LONDON/LUHRING AUGUSTINE, NEW YORK/GALLERIA LORCAN O?NEILL Ms. Whiteread came to three dimensions via two, after learning the casting process while a painting student at Brighton Polytechnic in the 1980s. She then studied sculpture at the Slade School of Art in London. -

Whitehot | January 2008, Tracy Emin, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills

wm | whitehot January 2008, Tracy Emin, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills http://www.whitehotmagazine.com/whitehot_articles.cfm?id=1120 WM homepage > whitehot Los Angeles whitehot | January 2008, Tracy Emin, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills Tracey Emin, You Left Me Breathing, courtesy Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills Tracy Emin You Left Me Breathing Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills Words by Jeremy von Stilb, Whitehot LA The hand drawn line, a scribble, a note written carelessly on a piece of paper. Such displays are rarely given any consideration beyond the purpose of their function. A grocery list, a quick measurement, a way to pass the time. It is this very gesture that is given great attention in the latest show at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills, California. This is Tracey Emin’s You Left Me Breathing; a show featuring works in various mediums that focus on the artist’s urgent and intimate actions. Unlike many artists of late, Tracey Emin looks no further than her own emotional landscapes to provide the viewer with access to many autobiographical moments detailing her joys and failures. It is a small privilege to be able to view her work outside of her native England. It benefits her in that the reputation she has in Britain means little on America shores as she is known for emotional breakdowns on television interviews, public drunkenness, well published spats with other artists and other forms of bad girl behavior typically reserved for a rock star rather than one of the country’s most notable contemporary artists. Without any knowledge of the coverage of her in various tabloids, one is able to view her work and encounter the emotional vulnerability and confrontational self-expression that has always been present in her art.