Ecommerce Business Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Technical Practice of Affiliate Marketing

A TECHNICAL PRACTICE OF AFFILIATE MARKETING Case study: coLanguage and OptimalNachhilfe LAHTI UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Degree programme in Business Information Technology Bachelor Thesis Autumn 2015 Phan Giang 2 Lahti University of Applied Sciences Degree Programme in Business Information Technology Phan, Huong Giang: Title: A technical practice of Affiliate Marketing Subtitle: Case study: coLanguage and OptimalNachhilfe Bachelor’s Thesis in Business 49 pages, 0 page of appendices Information technology Autumn 2015 ABSTRACT This study aims to introduce a new marketing method: Affiliate marketing. In addition, this study explains and explores many types of affiliate marketing. The study focuses on defining affiliate marketing methods and the technologies used to develop it. To clarify and study this new business and marketing model, the study introduces two case studies: coLanguage and OptimalNachhilfe. In addition, various online businesses such as Amazon, Udemy, and Google are discussed to give a broader view of affiliate marketing. The study provides comprehensive information about affiliate marketing both in its theoretical and practical parts, which include methods of implantation on the websites. Furthermore, the study explains the affiliate programs of companies: what they are and how companies started applying these programs in their businesses. Key words: Affiliate marketing, Performance Marketing, Referral Marketing, SEM, SEO, CPC, PPC. 3 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Aim of research 1 1.2 OptimalNachhilfe and coLanguage -

Title Author Contract Publisher Pub Year BISAC/LC Subject Heading Southern Illinois "Speech Acts" and the First Amendment Haiman, Franklyn Saul

Title Author Contract Publisher Pub Year BISAC/LC Subject Heading Southern Illinois "Speech Acts" and the First Amendment Haiman, Franklyn Saul. University Press 1993 LAW / Constitutional $$Cha-ching!$$ : A Girl's Guide to Spending and Rosen Publishing Saving Weeldreyer, Laura. Group 1999 JUVENILE NONFICTION / General [Green Barley Essence : The Ideal "fast Food" Hagiwara, Yoshihide NTC Contemporary 1985 MEDICAL / Nursing / Nutrition 1,001 Ways to Get Promoted Rye, David E. Career Press 2000 BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Careers / General 1,001 Ways to Save, Grow, and Invest Your BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Personal Finance Money Rye, David E. Career Press 1999 / Budgeting 100 Great Jobs and How to Get Them Fein, Richard Impact Publications 1999 BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Labor LANGUAGE ARTS & DISCIPLINES / Library & 100 Library Lifesavers : A Survival Guide for Information Science / Archives & Special School Library Media Specialists Bacon, Pamela S. ABC-CLIO 2000 Libraries 100 Top Internet Job Sites : Get Wired, Get LANGUAGE ARTS & DISCIPLINES / Library & Hired in Today's New Job Market Ackley, Kristina M. Impact Publications 2000 Information Science / General BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Investments & 100 Ways to Beat the Market Walden, Gene. Kaplan Publishing 1998 Securities / General Inlander, Charles B.-Kelly, People's Medical 100 Ways to Live to 100 Christine Kuehn. Society 1999 MEDICAL / Preventive Medicine 100 Winning Resumes for $100,000+ Jobs : LANGUAGE ARTS & DISCIPLINES / Resumes That Can Change Your Life Enelow, Wendy S. Impact Publications 1997 Composition & Creative Writing 1001 Basketball Trivia Questions Ratermann, Dale-Brosi, Brian. Perseus Books, LLC 1999 SPORTS & RECREATION / Basketball 101 + Answers to the Most Frequently Asked John Wiley & Sons, Questions From Entrepreneurs Price, Courtney H. Inc. -

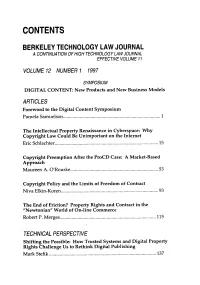

Contents Berkeley Technology Law

CONTENTS BERKELEY TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL A CONTINUATION OF HIGH TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL EFFECTIVE VOLUME 11 VOLUME 12 NUMBER 1 1997 SYMPOSIUM DIGITAL CONTENT: New Products and New Business Models ARTICLES Foreword to the Digital Content Symposium Pam ela Sam uelson ............................................................................ 1 The Intellectual Property Renaissance in Cyberspace: Why Copyright Law Could Be Unimportant on the Internet Eric Schlachter ................................................................................. 15 Copyright Preemption After the ProCD Case: A Market-Based Approach M aureen A . O 'Rourke ..................................................................... 53 Copyright Policy and the Limits of Freedom of Contract N iva Elkin-K oren ............................................................................ 93 The End of Friction? Property Rights and Contract in the "Newtonian" World of On-line Commerce R obert P . M erges ................................................................................ 115 TECHNICAL PERSPECTIVE Shifting the Possible: How Trusted Systems and Digital Property Rights Challenge Us to Rethink Digital Publishing M ark Stefik ......................................................................................... 137 ARTICLES (CONTINUED) Some Reflections on Copyright Management Systems and Laws Designed to Protect Them Ju lie E . C ohen ..................................................................................... 161 Chaos, Cyberspace and Tradition: Legal -

The Name "Affiliate Marketing" 76 References 76 Social Media Optimization 76 E-Mail Marketing 76

Bill Ganz www.BillGanz.com 310.991.9798 1 Bill Ganz www.BillGanz.com 310.991.9798 2 Introduction 10 Social Networking Industry 11 Section 1 - Belonging Networks 12 Social Networking - The Vast Breakdown 12 Belonging Networks 13 Engagement, Traffic, Planning and Ideas 14 Belonging Networks Themed Experiences 15 Intelligent Delivery 16 Online Vs. Offline Business Architecture 17 This is where consumers in an online world are able to collaborate with other like minded people with the same interests. Social networking allows people to poll other like minded and/or industry professionals for common consensus. 17 Belonging Network True Response 18 Marketeers! RSS & You 18 Section 2 - Social Networking Reference Manual 19 10 Most Beautiful Social Networks 19 Web 2.0 26 Web 3.0 34 Social network analysis 38 History of social network analysis 39 Applications 41 Business applications 42 Bill Ganz www.BillGanz.com 310.991.9798 3 Metrics (Measures) in social network analysis 42 Professional association and journals 44 Network analytic software 44 Social Networking Service 45 References 45 Content delivery network 46 Digital rights management 48 IPTV (Internet Protocol Television) 63 What do I need to experience IPTV? 63 How does IPTV work? 63 The Set Top Box 63 Affiliate marketing 64 History 64 Historic development 65 Web 2.0 66 Compensation methods 66 Predominant compensation methods 66 Diminished compensation methods 66 Compensation methods for other online marketing channels 67 CPM/CPC versus CPA/CPS (performance marketing) 67 Multi tier programs -

DIRTY LITTLE SECRETS of the RECORD BUSINESS

DIRTY BUSINESS/MUSIC DIRTY $24.95 (CAN $33.95) “An accurate and well-researched exposé of the surreptitious, undisclosed, W hat happened to the record business? and covert activities of the music industry. Hank Bordowitz spares no It used to be wildly successful, selling LI one while exposing every aspect of the business.” LI outstanding music that showcased the T producer of Talking Heads, T performer’s creativity and individuality. TLE SE —Tony Bongiovi, TLE Aerosmith, and the Ramones Now it’s in rapid decline, and the best music lies buried under the swill. “This is the book that any one of us who once did time in the music SE business for more than fifteen minutes and are now out of the life wish This unprecedented book answers this CR we had written. We who lie awake at nights mentally washing our hands CR question with a detailed examination LITTLE of how the record business fouled its as assiduously yet with as much success as Lady Macbeth have a voice DIRTYLITTLE ET DIRTY in Hank Bordowitz. Now I have a big book that I can throw at the ET own livelihood—through shortsighted- S liars, the cheats, and the bastards who have fooled me twice.” S ness, stubbornness, power plays, sloth, and outright greed. Dirty Little Secrets o —Hugo Burnham, drummer for Gang of Four, o f of the Record Business takes you on a former manager and major-label A&R executive f the the hard-headed tour through the corridors ofof thethe of the major labels and rides the waves “Nobody should ever even think about signing any kind of music industry SECRSECRETSETS contract without reading this book. -

RHSSUE '.'' a BILLBOARD SPOTLIGHT I' SEE PAGE 71 I 1,1Ar 1.1141101 101611.C, the Essential Electronic .' Music Collection

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) IN MUSIC NEWS IBXNCCVR **** * ** 3 -DIGIT 908 1190807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 576 001 032198 2 126 1256 3740 ELM A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Fogerty Is Back With Long- Awaited WB Set PAGE 11 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT r APRIL 19, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS Labels Testing Chinese Mkt. Urban Acts Put New Spin Liaison Offices Offer Domestic Link BY GEOFF BURPEE pendents: America's Cherry Lane On Spoken -Word Genre Music, Taiwan's Rock Records, and HONG KONG -As a means of Hong Kong's Fitto. However, these BY J.R. REYNOLDS itual enrichment. establishing and testing ties within companies (and others that would Labels are bowing projects by China's sprawling, underdeveloped like a presence) must r e c o g n i z e LOS ANGELES -A wave of releas- such young hip -hop and alternative - recording restraints on es by African- American spoken -word influenced artists as Keplyn and industry, their activi- acts will soon Mike Ladd, a- the "repre- SONY ties, such as begin flowing longside product sentative" EMI state con- through the retail by pre- hip -hop or "liaison" trols on lic- pipeline, as labels poets like Sekou office is be- ensing music attempt to tap Sundiata and coming an increasingly from outside of China and into growing con- such early -'70s valuable tool for interna- SM the lack of a developed sumer interest in spoken -word pio- tional music companies market within. the specialized neers as the Last Such units also serve as an As early as 1988, major recording genre. -

The Impact of E-Commerce Strategies on Firm Value : Lessons from Amazon.Com and Its Early Competitors

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Filson, Darren Working Paper The Impact of E-Commerce Strategies on Firm Value : Lessons from Amazon.com and its Early Competitors Claremont Colleges Working Papers, No. 2003-06 Provided in Cooperation with: Department of Economics, Claremont McKenna College Suggested Citation: Filson, Darren (2003) : The Impact of E-Commerce Strategies on Firm Value : Lessons from Amazon.com and its Early Competitors, Claremont Colleges Working Papers, No. 2003-06, Claremont McKenna College, Department of Economics, Claremont, CA This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/23381 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The Impact of E-Commerce Strategies on Firm Value: Lessons from Amazon.com and its Early Competitors Darren Filson* February 20, 2002 * Assistant professor, Department of Economics, Claremont Graduate University. -

Eastern Progress 1998-1999 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1998-1999 Eastern Progress 11-5-1998 Eastern Progress - 05 Nov 1998 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1998-99 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 05 Nov 1998" (1998). Eastern Progress 1998-1999. Paper 12. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1998-99/12 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1998-1999 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ► Accent ► Sports Business meals are no time to X^kThe Eastern clown around/A6 Progr www.progress.eku.eduess 'SSS^SSSSm'' Student publication of Eastern Kentucky University slnci Oldest campus dorm to be torn down Out with the old the project $20 million. That will must go in the building, such as O'Donnell Hall Is going to be New student services building to take place of O'Donnell cover the total scope of the project, housing, career services, counsel- torn down when construction will begin sometime next year. including architect fees, planning, ing, minority affairs, student gov- starts for the new student Bv DENA TACKETT the most likely place to start construction costs and the cost of ernment. Residence Hall services building next year. Eastern President Robert Kustra because it was the most expensive Association offices and disabilities Assistant news editor said. removing the existing building or to maintain and the oldest," buildings, Whitlock said. services. Tom Myers, vice president of Myers, along with James Street, Kustra also said that when look- "Every activity or function relat- student affairs, once had a dream. -

Stunde Der Wahrheit

Trends Start-ups Stunde der Wahrheit Start-up-Sterben: Gewinne? Fehlanzeige! Zukunftsaussichten? Ungewiss! Jetzt rächt sich, dass die jungen Internet-Firmen die Regeln der Alten Wirtschaft ignorierten. arlos Santana im Sonder- zester Zeit imitierten Konkurrenten angebot. 30 Prozent unter das verführerisch simple Konzept – Ladenpreis verscherbelt i Kompakt mit den im Handel üblichen Folgen: Jason Olim „Supernatural“ Die meisten Dot-com-Firmen wer- Die ohnehin geringen Margen ver- C– die Hit-Scheibe – im Internet. Mit den dieses Jahr nicht überleben. kehrten sich bei CD Now ins Minus. sensationell günstigen Preisen baute Warum sie scheitern: Ihr Ge- Ende 1999 summierten sich die seit der Vorstandschef von CD Now seine schäftsmodell ist zu leicht zu ko- der Gründung im Februar 1994 ange- virtuelle Musikalienhandlung zum pieren. Ihre Ideen sind fragwürdig. fallenen Verluste des hoch gelobten führenden Plattenladen im World Die Einnahmen werden über- Online-Pioniers aus Pennsylvania auf Wide Web auf. Millionen von Dollar schätzt, und es fehlt an professio- knapp 175 Millionen Dollar. Nun ver- steckte er in üppige Werbekampag- neller Umsetzung. Zudem drän- handelt Vorstandschef Olim über den nen, ohne zu überlegen, ob sich der gen etablierte Unternehmen ins Verkauf seines Unternehmens an ei- Aufwand je lohnen würde. E-Business – mit deutlich besseren nen finanzkräftigen Investor. Bislang Eine zunächst höchst erfolgreiche Chancen. ohne Ergebnis. CD Now hat schon Strategie. Zu erfolgreich. Binnen kür- zu viel Boden verloren. Findet Olim 196 managermagazin 6/00 Trends Start-ups nicht bald einen neuen Geldgeber, Eine verhängnisvolle Situation für den Vorzügen der New Economy zu droht der Konkursrichter. die Start-ups. Viele von ihnen wissen verbinden wissen, besser gerüstet In den USA sind Geschichten wie nicht mehr, wie sie Lieferanten und als die jungen Wilden? Ist die viel die von CD Now längst kein Einzelfall Mitarbeiter bezahlen sollen. -

1. About the Ant King and Other Stories by Benjamin Rosenbaum 2

1. About The Ant King and Other Stories by Benjamin Rosenbaum 2. Creative Commons License Summary: Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 3. Creative Commons Full License 4. The Ant King and Other Stories 1. The Ant King and Other Stories Benjamin Rosenbaum Published by Small Beer Press http://www.lcrw.net [email protected] August 5, 2008 Trade paper ISBN: 9781931520539 Trade cloth ISBN: 9781931520522 Some Rights Reserved The Ant King and Other Stories is a dazzling, postmodern debut collection of pulp and surreal fictions: a writer of alternate histo- ries defends his patron’s zeppelin against assassins and pirates; a woman transforms into hundreds of gumballs; an emancipated chil- dren’s collective goes house hunting. The Ant King and Other Stories is being released as a Free Download under Creative Commons license on August 5, 2008. If you’d like to get the book version, The Ant King and Other Stories is available from: Small Beer Press; your local bookshop; Powells; all the usual book shops and web sites, and is distributed to the trade by Consortium. This book is governed by Creative Commons licenses that permit its unlimited noncommercial redistribution, which means that you’re welcome to share it with anyone you think will want to see it. If you do something with the book you think we’d be interested in please email ([email protected]) and tell us. Thanks for reading. 2. Creative Commons License Summary: Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 3. License THE WORK (AS DEFINED BELOW) IS PROVIDED UNDER THE TERMS OF THIS CREATIVE COMMONS PUBLIC LICENSE (“CCPL” OR “LICENSE”). -

Getting Everything You Can out of All You've

Getting Everything You Can Out Of All You Got THE BOOK OF PERSONAL AND BUSINESS GROWTH By Jay Abraham 18 Super logical ways to multiply your talent, income and success in today’s new world of opportunity. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i. PART I: MAXIMIZING WHAT YOU HAVE Chapter 1: YOUR FLIGHT PLAN 1 Where You’re Headed – Understanding the Big Picture Chapter 2: GREAT EXPECTATIONS 30 The Art of Becoming Unbeatable Chapter 3: HOW CAN YOU GO FORWARD IF YOU DON’T KNOW WHICH WAY YOU’RE FACING? 45 Your Current Business Strengths and Weaknesses Chapter 4: YOUR BUSINESS SOUL – THE STRATEGY OF PREEMINENCE 52 How to Philosophically Approach Clients and Colleagues Chapter 5: BREAK EVEN TODAY, BREAK THE BANK TOMORROW 66 Calculating the Lifetime Value of a Client Chapter 6: VIVE LA DIFFERENCE 75 Developing a Unique Selling Proposition Chapter 7: MAKE ‘EM AN OFFER THEY CAN’T REFUSE 100 Risk Reversal – Eliminating the Number One Obstacle to Buying Chapter 8: WOULD YOU LIKE THE LEFT SHOE, TOO? 115 Increasing Client Satisfaction and Transaction Value Chapter 9: HOW TO NEVER FALL OFF A CLIFF 142 Testing to Guarantee the Highest Results and Lowest Risk PART II: MULTIPLYING YOUR MAXIMUM Chapter 10: WITH A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIENDS 159 Benefiting Through Host-Beneficiary Relationships Chapter 11: SOMEONE YOU SHOULD MEET 187 Creating a Formal Referral System Chapter 12: THE PRODIGAL CLIENT 206 Reactivating Past Clients and Relationships Chapter 13: YOUR 10,000 PERSON SALES DEPARTMENT 225 Gaining Clients with Sales Letters and the Written Word Chapter 14: