South Dakota Dn 0 Te S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

HANDBOOK 2018 Taking a Look Back! the First South Dakota Pheasant Hunting Season Was a One-Day Hunt Held in Spink County on October 3O, 1919

Hunting and trapping HANDBOOK 2018 Taking a look back! The first South Dakota pheasant hunting season was a one-day hunt held in Spink County on October 3O, 1919. Help the South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks tip our blaze orange caps to the past 100 years of Outdoor Tradition, and start celebrating the next century. Show us how you are joining in on the fun by using #MySDTradition when sharing all your South Dakota experiences. Look to the past, and step into the future with South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. Photo: South Dakota State Historical Society SOUTH DAKOTA GAME, FISH & PARKS HUNTING HANDBOOK CONSERVATION OFFICER DISTRICTS GENERAL INFORMATION: 605.223.7660 TTY: 605.223.7684, email: [email protected] Aberdeen: 605.626.2391, 5850 E. Hwy 12 Pierre: 605.773.3387, 523 E. Capitol Ave. Chamberlain: 605.734.4530, 1550 E. King Ave. Rapid City: 605.394.2391, 4130 Adventure Trail Ft. Pierre: 605.223.7700, 20641 SD Hwy 1806 Sioux Falls: 605.362.2700, 4500 S. Oxbow Ave. Huron: 605.353.7145, 895 3rd Street SW Watertown: 605.882.5200, 400 West Kemp Mobridge: 605.845.7814, 909 Lake Front Drive Webster: 605.345.3381, 603 E. 8th Ave. CONSERVATION OFFICERS *denotes District Conservation Officer Supervisor Martin Tom Beck 605.381.6433 Britton Casey Dowler 605.881.3775 Hill City Jeff Edwards 605.381.9995 Webster Austin Norton 605.881.2177 Hot Springs D.J. Schroeder 605.381.6438 Sisseton Dean Shultz 605.881.3773 Custer Ron Tietsort 605.431.7048 Webster Michael Undlin 605.237.3275 Spearfish Brian Meiers* 605.391.6023 Aberdeen Tim McCurdy* 605.380.4572 -

South Dakota Boating Laws and Responsibilities

the the OF SOUTH DAKOTA BOATING LAWS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 2015 Edition Copyright © 2015 Boat Ed, www.boat-ed.com Department of Game, Fish & Parks The purpose of the Department of Game, Fish & Parks is to perpetuate, conserve, manage, protect, and enhance South Dakota’s wildlife resources, parks, and outdoor recre- ational opportunities for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the people of this state and its visitors, and to give the highest priority to the welfare of this state’s wildlife and parks, and their environment, in planning and decisions. DIVISION OF WILDLIFE manages South Dakota’s wildlife and fisheries resources and their associ- ated habitats for their sustained and equitable use, and for the benefit, welfare, and enjoyment of the citizens of this state and its visitors. 605-223-7660 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION is committed to providing diverse outdoor recreational opportunities, acting as a catalyst for a growing tourism economy, and preserving the resources with which we are entrusted. We will accomplish this through efficient, responsive, and environmentally sensitive management and constructive communication with those we serve. 605-773-3391 South Dakota Game, Fish & Parks 523 East Capitol Avenue Pierre, SD 57501 www.gfp.sd.gov Copyright © 2015 Boat Ed, www.boat-ed.com the the OF SOUTH DAKOTA BOATING LAWS AND RESPONSIBILITIES Published by Boat Ed, a division of Kalkomey Enterprises, Inc., 14086 Proton Road, Dallas, TX 75244, 214-351-0461. Printed in the U.S.A. Copyright © 2005–2015 by Kalkomey Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any process without permission in writing from Kalkomey Enterprises, Inc. -

South Dakota Bi Rd N 0 Te S

SOUTH DAKOTA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION SOUT H DAKOTA B I RD N 0 TE S VOL. 45 JUNE 1993 NO. 2 SOUTH DAKOTA BIRDNOTES. the official publication of the South Dakota On'lithologiSts' Union (organized 1949), is sent to all members whose dues are paid for the current year. Life members $150.00; Family life members (husband and wife) with 1 subscription to Bird Notes $200: sustaining members $15.00, regular members $9.00; family members (husband and wife) wilh 1 subscription $12.00; juniors (10-1 6) $4.50; libraries (sub scription) $9.00. Single and back copies: Members $2.50, Nonmembers $3.00. All dues payments. change-of-address notices. and orders for back copies should be sent to the Treasurer, Nelda Holden, 1620 Elmwood Drive, Brookings, SD 57006. Manuscripts for publication should be sent to Editor Dan Tallman. NSU Box 740, Aberdeen SD, 57401. NO. 2 VOL. 45 JUNE 1993 IN THIS ISSUE RED-HEADED WOODPECKER by Melvin Bollinger ........................ Cover PRESIDEN'T'S PAGE ...................................... ..................... .. .......... ..... 23 1992 REPORr OF THE RARE BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE .. ............. 24 GENERAL NOTES-Third Documented State Nest Record of The Ruby- Throated Hummingbird at Pickerel Lake State Recreation Area; Golden Eagle Attacks Fox Squirrels; Abnormally Plumaged House Finch; Common Grackle Banded in Aberdeen Recovered in Arkansas; Philadelphia Vireos in Clay And Union Counties-Fall 1992; Whimbrels at Bear Butte Lake ........... ........ .......................... 28 BOOK REVIEWS ................................................................ .................. 32 SEASONAL REPORrS .................. ........................................................ 33 CHRISTMAS COUNTS ... ................ ............... ... .. .......... ... ...................... 36 SOlJfH DAKOTA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION Officers 1991-1992 President DenniS Skadsen, Box 113, Grenville 57239 Vice President J. David Williams, Box 277, Ipswich 57451 Secretary L. -

Sanitary Disposals Alabama Through Arkansas

SANITARY DispOSAls Alabama through Arkansas Boniface Chevron Kanaitze Chevron Alaska State Parks Fool Hollow State Park ALABAMA 2801 Boniface Pkwy., Mile 13, Kenai Spur Road, Ninilchik Mile 187.3, (928) 537-3680 I-65 Welcome Center Anchorage Kenai Sterling Hwy. 1500 N. Fool Hollow Lake Road, Show Low. 1 mi. S of Ardmore on I-65 at Centennial Park Schillings Texaco Service Tundra Lodge milepost 364 $6 fee if not staying 8300 Glenn Hwy., Anchorage Willow & Kenai, Kenai Mile 1315, Alaska Hwy., Tok at campground Northbound Rest Area Fountain Chevron Bailey Power Station City Sewage Treatment N of Asheville on I-59 at 3608 Minnesota Dr., Manhole — Tongass Ave. Plant at Old Town Lyman Lake State Park milepost 165 11 mi. S of St. Johns; Anchorage near Cariana Creek, Ketchikan Valdez 1 mi. E of U.S. 666 Southbound Rest Area Garrett’s Tesoro Westside Chevron Ed Church S of Asheville on I-59 Catalina State Park 2811 Seward Hwy., 2425 Tongass Ave., Ketchikan Mile 105.5, Richardson Hwy., 12 mi. N of on U.S. 89 at milepost 168 Anchorage Valdez Tucson Charlie Brown’s Chevron Northbound Rest Area Alamo Lake State Park Indian Hills Chevron Glenn Hwy. & Evergreen Ave., Standard Oil Station 38 mi. N of & U.S. 60 S of Auburn on I-85 6470 DeBarr Rd., Anchorage Palmer Egan & Meals, Valdez Wenden at milepost 43 Burro Creek Mike’s Chevron Palmer’s City Campground Front St. at Case Ave. (Bureau of Land Management) Southbound Rest Area 832 E. Sixth Ave., Anchorage S. Denali St., Palmer Wrangell S of Auburn on I-85 57 mi. -

South Dakota Boating Laws and Responsibilities

the the OF SOUTH DAKOTA BOATING LAWS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 2016 Edition Copyright © 2016 Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC and its divisions and partners, www.kalkomey.com Department of Game, Fish & Parks The purpose of the Department of Game, Fish & Parks is to perpetuate, conserve, manage, protect, and enhance South Dakota’s wildlife resources, parks, and outdoor recreational opportunities for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the people of this state and its visitors, and to give the highest priority to the welfare of this state’s wildlife and parks, and their environment, in planning and decisions. DIVISION OF WILDLIFE manages South Dakota’s wildlife and fisheries resources and their associated habitats for their sustained and equitable use, and for the benefit, welfare, and enjoyment of the citizens of this state and its visitors. 605-223-7660 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION is committed to providing diverse outdoor recreational opportunities, acting as a catalyst for a growing tourism economy, and preserving the resources with which we are entrusted. We will accomplish this through efficient, responsive, and environmentally sensitive management and constructive communication with those we serve. 605-773-3391 South Dakota Game, Fish & Parks 523 East Capitol Avenue Pierre, SD 57501 www.gfp.sd.gov Copyright © 2016 Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC and its divisions and partners, www.kalkomey.com the the OF SOUTH DAKOTA BOATING LAWS AND RESPONSIBILITIES Published by Boat Ed, a division of Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC, 14086 Proton Road, Dallas, TX 75244, 214-351-0461. Printed in the U.S.A. Copyright © 2005–2016 by Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any process without permission in writing from Kalkomey Enterprises, LLC. -

If Visiting SD State Parks

Bicycle Routes booklet_2003.qxd 05/02/2003 3:52 PM Page 16 SD State Parks 523 E Capitol Ave. Pierre, SD 57501 StateState ParkPark (605)(605) 773-3391 www.sdgfp.info/parks BicycleBicycle ToursTours PUBLISHED BY THE SD DIVISION OF PARKS & RECREATION BICYCLE TOURING GUIDE AND THE SD DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND RECOMMENDED ROUTES FOR SOUTH DAKOTA 31,250 copies of this brochure were printed at a cost of $.16 each. STATE PARKS & RECREATION AREAS Bicycle Routes booklet_2003.qxd 05/02/2003 3:48 PM Page 1 Welcome to SD state parks ... outho Dakota has welcomed the Smoniker “Land of Infinite Variety,” and one of the best ways to become acquainted with this land is by bicycle. Here, you’ll find eleven routes that connect South Dakota state parks and recreation areas through areas of flatland, rolling hills, vast prairie and croplands, wide lakes, meandering rivers, challenging climbs and scenic BICYCLE ROUTE LOCATIONS vistas. The routes are intended primarily for road cyclists, though distances and surfaces accommodate a wide variety of cycling abilities. If you prefer fat-tire cycling, state parks can accommodate you with a wide variety of trails throughout the state. Learn more about additional trail opportunities, including the George S. Mickelson Trail in the Black Hills, at the end of this booklet. We hope you enjoy South Dakota state parks by bicycle and encourage your feedback. Feel free to visit us online at www.sdgfp.info/Parks. Happy trails and tailwinds! Inside ...... How to use this guide . 2 (6) Big Stone Lake Tour . 9 Tips for an enjoyable ride . -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 South Dakota - 46 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District AURORA 332 - XXX D PLANKINTON TENNIS COURTS CITY OF PLANKINTON $2,082.00 C 5/4/1973 12/31/1975 1 379 - XXX D STICKNEY TENNIS COURTS CITY OF STICKNEY $4,999.84 C 4/22/1974 12/31/1976 1 471 - XXX D PLANKINTON PARK IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF PLANKINTON $6,190.03 C 1/20/1976 12/31/1977 1 486 - XXX D STICKNEY PARK IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF STICKNEY $7,931.42 C 2/2/1976 12/31/1978 1 678 - XXX D PLANKINTON POOL IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF PLANKINTON $42,231.92 C 1/17/1978 12/31/1980 1 811 - XXX D FISH LAKE GOLF COURSE IMP. AURORA COUNTY $57,454.10 C 7/11/1979 12/31/1983 1 824 - XXX R STICKNEY BALLFIELD IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF STICKNEY $8,987.22 C 7/10/1979 12/31/1983 1 AURORA County Total: $129,876.53 County Count: 7 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 2 South Dakota - 46 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District BEADLE 16 - XXX D HURON MEMORIAL PARK CITY OF HURON $12,049.68 C 12/6/1966 12/31/1968 1 35 - XXX D HURON MUNICIPAL SWIMMING POOL CITY OF HURON $107,639.02 C 4/13/1967 12/31/1968 1 100 - XXX D HURON TENNIS COURTS CITY OF HURON $10,541.22 C 12/31/1970 12/31/1971 1 132 - XXX A HURON MEADOWBROOK GOLF COURSE CITY OF HURON $2,500.00 C 3/23/1970 12/31/1972 1 181 - XXX D HURON MEADOWBROOK GOLF COURSE CITY OF HURON $76,434.34 C 2/19/1971 12/31/1973 1 208 - XXX D HURON RECREATION FACILITIES CITY OF HURON $13,561.19 C 1/20/1972 12/31/1973 1 334 - XXX D HURON PK IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF HURON $8,951.82 C 5/3/1973 12/31/1974 1 356 - XXX C WESSINGTON ACQ. -

Guidelines for Identifying and Evaluating Buried Archaeological Sites

A Geoarchaeological Overview of South Dakota and Preliminary Guidelines for Identifying and Evaluating Buried Archaeological Sites Final Report by Joe Alan Artz Joe Alan Artz Principal Investigator Contract Completion Report 1868 Office of the State Archaeologist The University of Iowa Iowa City 2011 The activity that is the subject of this Allocations Guide has been financed in part with the Federal funds from the National Park Service, U. S. Department of the Interior. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the American With Disabilities Act of 1990, and South Dakota law SDCL 20-13, the State of South Dakota and U. S. Department of the Interior prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, sex, disability, ancestry or national origin. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: South Dakota Division of Human Rights, State Capital, Pierre, SD 57501, or the Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 201 I Street NW, Washington, D. C. 20240. ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................................ -

South Dakota Sportsman Face an Important Vote on the Next Governor

1 888 overbag or 1-888-683-7224 JULY AUGUST 2018 Affiliated with the National Wildlife Federation VOLUME 58, NUMBER 4 Inside this issue: Pheasant Survey Indicates 47% Increase for Page 2 South Dakota’s 100th Hunting Season EXEC.DIRECTOR’S UPDATE According to the South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks (GFP), this year’s to preserving pheasant hunting for another century.” pheasant brood survey shows a 47 percent increase over last year. The Page 3 The Walk-in Area (WIA) program added 39,000 new acres in addition 2018 statewide pheasants-per-mile (PPM) index is 2.47, up from the to 8,000 new acres last year. With 1.1 million acres of public hunting PRESIDENTS COLUMN 2017 index of 1.68. land within the heart of South Dakota’s pheasant range, great SPORTSMAN AGAINST HUNER “A substantial increase in the pheasants-per-mile index is an exciting opportunities remain for public access to pheasant hunting. Hepler prospect for South Dakota’s 100th pheasant hunting season this said hunters should notice far fewer disturbed CRP fields compared Page 4 - 5 fall,” stated Kelly Hepler, GFP Secretary. “Weather conditions to last year when emergency haying and grazing was authorized in BOD - JOE LONG continue to play a significant role when it comes to bird numbers and response to severe drought conditions. better weather helped this year with the average pheasant brood size The annual hunting atlas and a web-based interactive map of public Convention Honorees increasing 22 percent over last year.” lands and private lands leased for public hunting can be found at https:// Sportsman - Next Gov. -

South Dakota Periodicals Index: 1982-1986 Clark N

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Hilton M. Briggs Library Faculty Publications Hilton M. Briggs Library 6-1-1987 South Dakota Periodicals Index: 1982-1986 Clark N. Hallman South Dakota State University Mary E. Caspers South Dakota State University, [email protected] Lisa F. Lister South Dakota State University Deb Gilchrist South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/library_pubs Recommended Citation Hallman, Clark N.; Caspers, Mary E.; Lister, Lisa F.; and Gilchrist, Deb, "South Dakota Periodicals Index: 1982-1986" (1987). Hilton M. Briggs Library Faculty Publications. Paper 5. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/library_pubs/5 This Index is brought to you for free and open access by the Hilton M. Briggs Library at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hilton M. Briggs Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Dakota Periodicals Index 1982-1986 Hilton M. Briggs Library South Dakota State University Brookings, South Dakota 1987 SOUTH DAKOTA PERIODICALS INDEX 1982-1986 Compiled By- Clark N. Hallman Mary E. Caspars Lisa F. Lister Deb Gilchrist Reference Department Hiltoni M. Briggs Library South Dakota State University Brookings, SD 57007-1098 1987 Publication of this indexwas funded in part by a grant from the South DakotaCommittee on the Humanities, ^ an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. LB 056 Introduction The South Dakota Periodicals Index is a subject and author index to selected periodicals and annuals published in South Dakota. -

Dakota !Bi'td Cnote1

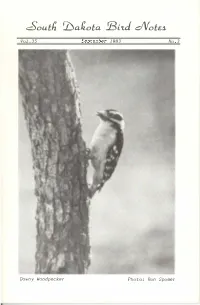

cSouth 'Dakota !Bi'td cNote1. Vol .35 September 1983 No.3 Downy Woodpecker Photo: Ron Spomer South Dakota Bird Notes, the official publication of the South Dakota Or nithologists' Union (organized 1949), is sent to all members whose dues are paid for the current year. Life members $125; sustaining members $12.00; regular members $6.00; family members (husband and wife) with one subscription to Bird Notes $9.00; juniors (10-16) $3.00; libraries (subscription) $6.00. Single and back copies: Members $1.50, Non members $2.00. All dues payments, change-of-address notices, and orders for back numbers should be sent to the Treasurer, Nelda flolden, Rt. 4, Box 252, Brookings SD 57006. All manuscripts for publication should be sent to Editor Dan Tallman, NSC Box 740, Aberdeen SD 57401. Vol .35 September 1983. No.3 IN THIS ISSUE President's Page •.•••••••••••••••••••••••••••�·············43 An Analysis of the Avifauna of an Isolated Ponderosa Pine Forest in Eastern Meade Co., South Dakota, Dan Tallman ••••44 General Notes--Kentucky Warbler in Lake County, Cinnamon Teal near Sioux Falls, Bird Banding Report 1982, Grosbeak Quandary, Herons, Egrets, and Ibis Nesting at Lake Preston, Pygmy Nuthatches Nesting in the Southern Hil ls, Late Date for Turkey Vulture in Spink County, Warbling Vireo in El Salvador and a 1982 Banding Report.50 Correction •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••55 Book Reviews, Dan Tallman ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••56 The 1983 Spring Season, Bruce Harris ••••.•••••••••••••••••57 SOUTH DAKOTA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION OFFICERS: 1981-1982 President Gil Blankespoor,Augustana College, Sioux Falls 57197 Vice President Galen Steffen, Burke 57523 Secretary L.M. Baylor, 1941 Red Dale, Rapid City 57701 Treasurer Nelda Holden, Rt.