AAIB Bulletin 4/2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Commons Official Report

Monday Volume 650 26 November 2018 No. 212 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 26 November 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

PLACE and INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised Page Numbers Refer to Extended Entries

PLACE AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised page numbers refer to extended entries Aachcn, 549, 564 Aegean North Region. Aktyubinsk, 782 Alexandroupolis, 588 Aalborg, 420, 429 587 Akure,988 Algarve. 1056, 1061 Aalst,203 Aegean South Region, Akureyri, 633, 637 Algeciras, I 177 Aargau, 1218, 1221, 1224 587 Akwa Ibom, 988 Algeria, 8,49,58,63-4. Aba,988 Aetolia and Acarnania. Akyab,261 79-84.890 Abaco,178 587 Alabama, 1392, 1397, Al Ghwayriyah, 1066 Abadan,716-17 Mar, 476 1400, 1404, 1424. Algiers, 79-81, 83 Abaiang, 792 A(ghanistan, 7, 54, 69-72 1438-41 AI-Hillah,723 Abakan, 1094 Myonkarahisar, 1261 Alagoas, 237 AI-Hoceima, 923, 925 Abancay, 1035 Agadez, 983, 985 AI Ain. 1287-8 Alhucemas, 1177 Abariringa,792 Agadir,923-5 AlaJuela, 386, 388 Alicante, 1177, 1185 AbaslUman, 417 Agalega Island, 896 Alamagan, 1565 Alice Springs, 120. Abbotsford (Canada), Aga"a, 1563 AI-Amarah,723 129-31 297,300 Agartala, 656, 658. 696-7 Alamosa (Colo.). 1454 Aligarh, 641, 652, 693 Abecbe, 337, 339 Agatti,706 AI-Anbar,723 Ali-Sabieh,434 Abemama, 792 AgboviIle,390 Aland, 485, 487 Al Jadida, 924 Abengourou, 390 Aghios Nikolaos, 587 Alandur,694 AI-Jaza'ir see Algiers Abeokuta, 988 Agigea, 1075 Alania, 1079,1096 Al Jumayliyah, 1066 Aberdeen (SD.), 1539-40 Agin-Buryat, 1079. 1098 Alappuzha (Aleppy), 676 AI-Kamishli AirpoI1, Aberdeen (UK), 1294, Aginskoe, 1098 AI Arish, 451 1229 1296, 1317, 1320. Agion Oras. 588 Alasb, 1390, 1392, AI Khari]a, 451 1325, 1344 Agnibilekrou,390 1395,1397,14(K), AI-Khour, 1066 Aberdeenshire, 1294 Agra, 641, 669, 699 1404-6,1408,1432, Al Khums, 839, 841 Aberystwyth, 1343 Agri,1261 1441-4 Alkmaar, 946 Abia,988 Agrihan, 1565 al-Asnam, 81 AI-Kut,723 Abidjan, 390-4 Aguascalientes, 9(X)-1 Alava, 1176-7 AlIahabad, 641, 647, 656. -

Airborne for Pleasure

Albert Morgan KNE wte> A Guide to Flying, Gliding, Ballooning and Parachuting AIRBORNE FOR PLEASURE ALSO FROM DAVID & CHARLES The Aviator's World, by Michael Edwards Instruments of Flight, by Mervyn Siberry AIRBORNE FOR PLEASURE A Guide to Flying, Gliding, Ballooning and Parachuting ALBERT MORGAN DAVID & CHARLES NEWTON ABBOT LONDON NORTH POMFRET (VT) VANCOUVER To my wife Betty, and daughters Susan andjanice, who managed not only to hold their breath during my aerial researches but also, more incredibly, their tongues ISBN o 7153 6477 4 LOG 74 20449 © Albert Morgan 1975 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of David & Charles (Holdings) Limited Set in ii on i3pt Garamond and printed in Great Britain by Latimer Trend & Company Ltd Plymouth for David & Charles (Holdings) Limited South Devon House Newton Abbot Devon Published in the United States of America by David & Charles Inc North Pomfret Vermont 0505 3 USA Published in Canada by Douglas David & Charles Limited 132 Philip Avenue North Vancouver BC CONTENTS Chapter Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 7 INTRODUCTION 9 1 FLYING FOR FUN 13 2 LEARNING TO FLY 32 3 RULES OF THE AIR 44 4 THE HELICOPTER 48 5 FINANCE FOR FLYING 5 J 6 GLIDING AS A SPORT 63 7 LIGHTER THAN AIR 79 8 PARACHUTING 94 APPENDICES: A. Where to Fly in B. Where to Glide 119 C. Where to Balloon, Parascend or Hang-Glide 123 D. -

Egad, Newtownards Airport Visiting Aircraft Guide

EGAD, NEWTOWNARDS AIRPORT VISITING AIRCRAFT GUIDE EGAD – Newtownards Airport 028 9181 3327 [email protected] 128.300MHz Local Chart NOT TO BE USED FOR NAVIGATION EGAD – Newtownards Airport 028 9181 3327 [email protected] 128.300MHz Airport Chart EGAD – Newtownards Airport 028 9181 3327 [email protected] 128.300MHz Airfield Information • All circuit traffic is left hand except RW03 which is right hand. • Standard circuit height is 1000ft agl and aerodrome elevation is 9ft. • Please avoid overflying Castle Espie bird sanctuary. (185° at 3nm from EGAD) • Standard overhead join recommended at 2000ft agl if possible. Runway Information Runway PAPI LIGHTS TODA LDA 03 4.5º Yes 747m 791m 08 - - 566m Unlicensed 15 4.5º Yes 594m 530m 21 4.5º Yes 791m 717m 26 - - Unlicensed 566m 33 4.5º Yes 586m 564m 15 Grass - 0 Unlicensed Unlicensed Remarks / Warnings Approaches to Runway 26 & 33 are directly over a sea wall which may be obstructed by persons and vehicles 15 Approach / 33 Climb out, Police station mast to the east of the centreline (153ft) Air Traffic Services Information • An Air/Ground service on frequency 128.300. Callsign ‘Newtownards Radio’ • Belfast Approach on frequency 130.850. Callsign ‘Belfast Approach’ Diversion Airfields • EGAC, Belfast City (289° at 6.7nm) NO AVGAS AVAILABLE o RW04/22 - 1829 x45m, equipped with ILS both ends • EGAA, Aldergrove (284° at 10nm) o RW07/25 - 2780 x45m, equipped with VOR 07 & ILS 25 o RW17/35 – 1891x45m, equipped with ILS 17 & VOR 35 o Aircraft Maintenance available EGAD – Newtownards Airport 028 9181 3327 [email protected] 128.300MHz Arrival & Departure Procedures NOT TO BE USED FOR NAVIGATION Arrivals • Aircraft arriving from the east / south will be able to route directly to the airfield below 2000ft. -

Draft Planning Policy Statement 18 Renewable Energy Public Consultation Draft

Planning and Natural Resources Division Planning and Environmental Policy Group Draft Planning Policy Statement 18 Renewable Energy Consultation Paper 23 November 2007 How to give your views You are invited to send your views on this Draft Planning Policy Statement, PPS18 ‘Renewable Energy’. Draft PPS 18 sets out the Department of the Environment’s planning policy for development that generates energy from renewable resources. The PPS also contains policy provisions on the application of the principles of Passive Solar Design in new development. Comments should reflect the structure of the document as much as possible with references to paragraph numbers where relevant. All responses should be made in writing and emailed to: [email protected] or sent by post to: Stephen Hamilton PPS 18 Renewable Energy Consultation Planning and Environmental Policy Group, Department of the Environment 12th Floor River House, 48 High Street, BELFAST, BT1 2AW The consultation period will end on Friday 21 March 2008 Draft PPS18 is available on the Planning Service website: www.planningni.gov.uk or can be obtained by telephoning (028) 9054 7713, textphone at (028) 9054 0642 or by writing to the above address. Should you require a copy of this document in an alternative format, it can be made available on request in large print, disc, Braille or audiocassette. It may also be made available in minority languages for those who are not proficient in English. In keeping with our policy on openness, the Department may make responses to this consultation document publicly available upon request. At the end of the consultation period the Department will consider all comments received, following which the draft documents will be amended if necessary and, subject to Ministerial approval, published in final form. -

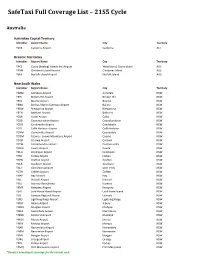

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Development and Opportunity / Ards and North Down / MIPIM 2020

DEVELOPMENT AND OPPORTUNITY 03 / 2020 Aberdeen Scotland Glasgow Edinburgh Londonderry Newcastle Belfast Isle of Man Blackpool Ireland Leeds/Bradford Manchester Dublin Liverpool Shannon Wales Cork England Cardiff London Bristol Exeter Southampton Portrush Ballycastle Coleraine Londonderry Ballymena Larne Strabane Magherafelt Bangor Northern Belfast Ireland Dungannon Portadown Portaferry Enniskillen Downpatrick Bangor Newcastle Newry Holywood Donaghadee Newtownards Comber www.ardsandnorthdown.gov.uk /2 Overview Ards and North Down (AND) is a unique location with easy access to Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland. It is adjacent to Belfast; offers excellent digital and transport connectivity; is home to a highly educated workforce and offers an outstanding natural environment. Number 1 excellent connectivity and global reach Drivers Number one full fibre ultra-fast broadband connectivity in NI, and for Business second in the whole of the UK (Connected Nations 2019 - Ofcom) and Success offers a comprehensive infrastructure of road and rail links to nearby air and seaports for excellent global reach. Ards and North Down Borough Council are the No. 1 ranked council in Northern Ireland for Full Fibre availability of premises, and of the 383 councils in the whole of the UK, Ards and North Down Borough Council are ranked No. 2 High skills and low Strong appeal to attract operating costs and retain talent Combining skilled and highly The region offers an ideal work/life balance location for employees with educated local workforce with an outstanding quality of life, 185 km of coastline and beautiful landscape competitive operating costs reached within minutes of Belfast City Centre. The borough also includes the ensures that Ards and North town of Holywood – Regional winner of ‘The Times Best Places to Live in the Down is a highly appealing place UK 2019’. -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

Safetaxi Europe Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Europe Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Albania Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country LATI Tirana International Airport Tirana Albania Armenia Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UDSG Shirak International Airport Gyumri Armenia UDYE Erebuni Airport Yerevan Armenia UDYZ Zvartnots International Airport Yerevan Armenia Armenia-Georgia Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UGAM Ambrolauri Airport Ambrolauri Armenia-Georgia UGGT Telavi Airport Telavi Armenia-Georgia UGKO Kopitnari International Airport Kutaisi Armenia-Georgia UGSA Natakhtari Airport Natakhtari Armenia-Georgia UGSB Batumi International Airport Batumi Armenia-Georgia UGTB Tbilisi International Airport Tbilisi Armenia-Georgia Austria Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country LOAV Voslau Airport Voslau Austria LOLW Wels Airport Wels Austria LOWG Graz Airport Graz Austria LOWI Innsbruck Airport Innsbruck Austria LOWK Klagenfurt Airport Klagenfurt Austria LOWL Linz Airport Linz Austria LOWS Salzburg Airport Salzburg Austria LOWW Wien-Schwechat Airport Wien-Schwechat Austria LOWZ Zell Am See Airport Zell Am See Austria LOXT Brumowski Air Base Tulln Austria LOXZ Zeltweg Airport Zeltweg Austria Azerbaijan Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UBBB Baku - Heydar Aliyev Airport Baku Azerbaijan UBBG Ganja Airport Ganja Azerbaijan UBBL Lenkoran Airport Lenkoran Azerbaijan UBBN Nakhchivan Airport Nakhchivan Azerbaijan UBBQ Gabala Airport Gabala Azerbaijan UBBY Zagatala Airport Zagatala Azerbaijan Belarus Identifier Aerodrome Name City Country UMBB Brest Airport Brest Belarus UMGG -

Ards and North Down Borough Council a G E N

ARDS AND NORTH DOWN BOROUGH COUNCIL 25 September 2019 Dear Sir/Madam You are hereby invited to attend a meeting of the Planning Committee of the Ards and North Down Borough Council which will be held in the Council Chamber, 2 Church Street, Newtownards on Tuesday, 1 October 2019 commencing at 7.00pm. Tea, coffee and sandwiches will be available from 6.00pm. Yours faithfully Stephen Reid Chief Executive Ards and North Down Borough Council A G E N D A 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Matters arising from minutes Planning Committee Meeting of 3 September 2019 (Copy attached) 4. Planning Applications Construction of discount food store, provision of car parking, landscaping and associated site works (relocation of existing supermarket at No. 1 Jubilee Road – supermarket to be retained but food store use to be extinguished and transferred to the 4.1 LA06/2018/1388/F application site) Undeveloped land bounded by Castlebawn Drive to the East immediately opposite and West of Castlebawn Retail Park, and approximately 120m North of Messines Road (otherwise known as the A20 Southern Relief Road), Newtownards 5. Update on Planning Appeals (Report attached) 6. Planning Budgetary Control Report – August 2019 (Report attached) 7. Proposed Amendment to Scheme of Delegation (Report attached) 7b. Outcome of DFI Planning Visits to Planning Committees (Report attached) 7c. Planning Monitoring Framework (Report attached) 8. Governance Arrangements for Local Development Plan (LDP) (Report attached) 9. Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council Consultation and Engagement Strategy (Report attached) 10. Update from Metropolitan Area Spatial Working Group MASWG – Local Development Plan (Report attached) 11. -

Download 5 September Agenda

ARDS AND NORTH DOWN BOROUGH COUNCIL 29 August 2019 Dear Sir/Madam You are hereby invited to attend a meeting of the Regeneration and Development Committee of the Ards and North Down Borough Council which will be held in the Council Chamber, 2 Church Street, Newtownards on Thursday 5 September 2019 commencing at 7.00pm. Tea, coffee and sandwiches will be available from 6.00pm. Yours faithfully Stephen Reid Chief Executive Ards and North Down Borough Council A G E N D A 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Pickie Funpark Quarter 1 2019/20 (Report attached) 4. Bangor Marina Quarter 1 (Report attached) 5. Gifted Craft Fair 2019 (Report attached) 6. GAP Programme 2019-2020 – The Growth Achievement Programme (Report attached) 7. Economic Development Performance Report Q1 2019/20 (Report attached) 8. Regeneration and Development Budgetary Control Report – July 2019 (Copy attached) 9. Regeneration Unit Performance Report Q1 2018/19 (Report attached) 10. Tourism Service Unit Performance Quarter 1, 2019/20 (Report attached) 11. Ards and Bangor Business Awards (Report attached) 12. Women in Business Awards 7 Nov 2019 – Crowne Plaza Hotel – Attendance & Support (Report attached) 13. Food and Drink Development Update (Report attached) 14. Tourism Development Update (Report attached) 15. Notice of Motion Update on North Channel Swim Interpretive Panel and Commemorative Medal (Copy attached) 16. Economic Impact of Pipe Band Championship in Newtownards 2019 (Report attached) 17. Visit Belfast End of Year Report 2018/19 (Report attached) 18. Exploris Car Park Development (Report attached) 19. Village Renewal – RDP Capital Application – Village Signage Scheme (Report attached) 20. -

AIR PILOT MASTER 24/01/2019 14:54 Page 1 2 Airpilot FEBRUARY 2019 ISSUE 31 AIR PILOT FEB 2019:AIR PILOT MASTER 24/01/2019 14:54 Page 2

AIR PILOT FEB 2019:AIR PILOT MASTER 24/01/2019 14:54 Page 1 2 AirPilot FEBRUARY 2019 ISSUE 31 AIR PILOT FEB 2019:AIR PILOT MASTER 24/01/2019 14:54 Page 2 Diary FEBRUARY 2019 AIR PILOT 12th Lunch Club RAF Club THE HONOURABLE 14th GP&F Cutlers’ Hall COMPANY OF AIR PILOTS 25th Aptitude Testing RAF Cranwell incorporating 26Cth T Dowgate Hill Air Navigators MARCH 2019 PATRON: His Royal Highness 7th GP&F Cutlers’ Hall The Prince Philip Court Cutlers’ Hall Duke of Edinburgh KG KT 25th AGM Merchant Taylors’ Hall GRAND MASTER: 29th United Guilds Service His Royal Highness The Prince Andrew APRIL 2019 Duke of York KG GCVO 4th GP&F Cutlers’ Hall MASTER: 11th ACEC TBA Captain Colin Cox FRAeS 24th Lunch Club RAF Club CLERK: 24th Cobham Lecture RAF Club Paul J Tacon BA FCIS Incorporated by Royal Charter. A Livery Company of the City of London. Please note that meetings scheduled for Dowgate Hill may be relocated to our new PUBLISHED BY: office depending on the date of our move. The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Dowgate Hill House, 14- 16 Dowgate Hill, London EC4R 2SU. EDITOR: VISITS PROGRAMME Paul Smiddy BA (Econ), FCA Please see the flyers accompanying this issue of Air Pilot or contact Liveryman David EMAIL: [email protected] Curgenven at [email protected]. These flyers can also be downloaded from the Company's website. FUNCTION PHOTOGRAPHY: Please check on the Company website for visits that are to be confirmed. Gerald Sharp Photography View images and order prints on-line.