At the Water's Edge by Janet R. Kirchheimer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Zero 08-17-17

TIME ZERO Written by Carlo Carere and Erin Carere Carlo Carere [email protected] (323) 237-3340 Erin Muir [email protected] (323) 425-2197 INT. INDOOR BASKETBALL COURT - DAY The center circle bears the CIA SEAL. TWO AGENTS at play: CIA CHIEF AGENT LOU BLACK, 33, hardcore and threatening, skillfully scores a three-pointer. CIA AGENT ROUNDER, 43, slightly overweight, snatches up the ball and tries to dodge Lou. In vain. ROUNDER All I’m saying is, for every terrorist we take out, five more pop up. Clockwork. So what if we tried something else? Other ways. LOU Any other way would convey that we’re weak and they’re in charge. Lou steals the ball and scores again. Rounder scoffs. ROUNDER Most of these people go rotten because all they have to look forward to is a shitty future. What if we somehow offered them a better one? LOU Wouldn’t work, Rounder. These people, the only thing they understand? Violence. ROUNDER You know, Lou, sometimes you might find it useful to be open to other ideas, especially ones from more experienced colleagues. Rounder goes for a three-pointer. A FAIL. Lou takes the ball and bounces it between ROUNDER’S LEGS. Rounder trips as Lou scores. Rounder, on the floor, acknowledges defeat. LOU More experienced, huh? How’s that working out for ya, Roundhouse? Lou smiles and helps Rounder up. LOU’S TELEPHONE rings. LOU Go ahead, Director. 2. Alarm floods his face. EXT. HOSPITAL - DAY A huge building with a sign: CHARITY HOSPITAL. A mob of POLICE, MEDIA and alarmed BYSTANDERS gather in front. -

Heart Care Handbook ABOUT THIS HANDBOOK

Patient Education intermountainhealthcare.org/heart Heart Care Handbook ABOUT THIS HANDBOOK This handbook won’t teach you everything you need or want to know about heart disease and heart-healthy living. But it will give you a good start. To write this book, we consulted local experts as well as the latest guidelines and recommendations of national organiza- tions such as the American Heart Association (AHA), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). All of these resources are listed in Chapter 10, along with cardiac rehab programs, books, and other trusted websites to help you learn more. You don’t need to read this book from front to back. Use the Table of Contents in the front of the book (or on the first page of each chapter) to help you find what you need. Use the book for a long-term reference. Make notes in the margins, highlight important informa- tion, and add notes from your healthcare providers and cardiac rehabilitation staff. If you have questions, talk with your healthcare providers. And don’t be afraid to accept help from concerned loved ones and friends. With support and treatment, you can manage your disease and lead a healthier and happier life. Contents INTRODUCTION Looking Ahead . 5 Your cardiac care team • The role of cardiac rehab • Your emotional needs: what you may feel CHAPTER Going Home . 9 1 Heart attack: what happened • Open heart surgery: what happened • Beyond the ICU • Recovering at home • Recordkeeping during home recovery • When to seek medical care Understanding Heart Disease . -

Het Verhaal Van De 340 Songs Inhoud

Philippe Margotin en Jean-Michel Guesdon Rollingthe Stones compleet HET VERHAAL VAN DE 340 SONGS INHOUD 6 _ Voorwoord 8 _ De geboorte van een band 13 _ Ian Stewart, de zesde Stone 14 _ Come On / I Want To Be Loved 18 _ Andrew Loog Oldham, uitvinder van The Rolling Stones 20 _ I Wanna Be Your Man / Stoned EP DATUM UITGEBRACHT ALBUM Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down The Road Apiece ALBUM DATUM UITGEBRACHT 10 januari 1964 EP Everybody Needs Somebody To Love Under The Boardwalk DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : (er zijn ook andere data, zoals DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : 17 april 1964 16, 17 of 18 januari genoemd Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down Home Girl I Can’t Be Satisfi ed 15 januari 1965 Label Decca als datum van uitbrengen) 14 augustus 1964 You Can’t Catch Me Pain In My Heart Label Decca REF : LK 4605 Label Decca Label Decca Time Is On My Side Off The Hook REF : LK 4661 12 weken op nummer 1 REF : DFE 8560 REF : DFE 8590 10 weken op nummer 1 What A Shame Susie Q Grown Up Wrong TH TH TH ROING (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 FIVE I Just Want To Make Love To You Honest I Do ROING ROING I Need You Baby (Mona) Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) Little By Little H ROLLIN TONS NOW VRNIGD TATEN EBRUARI 965) I’m A King Bee Everybody Needs Somebody To Love / Down Home Girl / You Can’t Catch Me / Heart Of Stone / What A Shame / I Need You Baby (Mona) / Down The Road Carol Apiece / Off The Hook / Pain In My Heart / Oh Baby (We Got A Good Thing SONS Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) If You Need Me Goin’) / Little Red Rooster / Surprise, Surprise. -

Spectrum 2016-2017 SHS Literary Magazine

Spectrum 2016-2017 SHS Literary Magazine This literary magazine is dedicated to Dr. Murphy, who inspires and teaches us every day. 2 Special thanks to our sponsors! Gary Andrews The Demars 3 Letters from the Editors Dear Reader, Being a part of something as wonderful as this literary magazine for the second year in a row is a gift. Being the co-editor-in-chief of it during my senior year is an honor. I started the year viewing it as a huge undertaking and responsibility, but as the year went on, the process happened naturally and easily. It could not have been done without the teamwork and dedication of the entire lit mag staff. I am grateful to every one of them for the constant input and constructive criticism. The final product is something I am incredibly proud of, and there is no way I could have accomplished it alone. I am extremely thankful to be a co-editor-in-chief because I would have had a much harder time doing all of this alone. I am also grateful for the beautiful art that was custom-made for our pieces by the talented students in the Sequoyah art program. The art brought the stories to life and was the perfect cherry on the sundae for our literary magazine. I am thankful for all the work that went into this, and for you, who is taking the time to read and appreciate it all. Thank you for letting me be a part of something so beautiful. Sincerely, Alexis Demar Dear Readers, With a theme like spectrum, there’s not really anything more that needs stated. -

A Change Is Gonna Come”—Sam Cooke (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by B.G

“A Change is Gonna Come”—Sam Cooke (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by B.G. Rhule (guest post)* Sam Cooke Recalling Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” So much has been written over these many decades about “A Change is Gonna Come,” Sam Cooke’s mellifluous and soulful ode to the struggles, yet prevailing hopes, of a black citizen living under the oppression of Jim Crow laws in the segregated South, that one may wonder, with 2019 approaching to mark the 55th year of its release to the public, exactly what is left to learn of the song’s etymology, and how it may be inextricably bound to the life experiences of its composer /lyricist. The answer, succinctly put, is plenty. Furthermore, unknown to the public are several intrinsic, key factors related to Sam Cooke’s personal and professional lives that, ironically, were played out against the backdrop of the Civil Rights era in which he lived and worked. It is a commonly held truth by those who knew and worked with Sam that the song was first inspired by the awe he felt and expressed for singer Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.” During a dinner break from his on-the-road performance travels, Sam, in the company of his band, tuned on the hotel room TV to watch the now-infamous 1963 March on Washington, and heard Dylan’s stirring and equally infamous anti-Jim Crow folk protest ballad. Yet, contrary to what some have written in stating that Sam was “angry” that a white boy wrote the song (which would have run totally counter to his lack of prejudice, a fact bolstered by his -

The Rolling Stones Complete Recording Sessions 1962 - 2020 Martin Elliott Session Tracks Appendix

THE ROLLING STONES COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1962 - 2020 MARTIN ELLIOTT SESSION TRACKS APPENDIX * Not Officially Released Tracks Tracks in brackets are rumoured track names. The end number in brackets is where to find the entry in the 2012 book where it has changed. 1962 January - March 1962 Bexleyheath, Kent, England. S0001. Around And Around (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (1.21) * S0002. Little Queenie (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (4.32) * (a) Alternative Take (4.11) S0003. Beautiful Delilah (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.58) * (a) Alternative Take (2.18) S0004. La Bamba (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (0.18) * S0005. Go On To School (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.02) * S0006. I'm Left, You're Right, She's Gone (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.31) * S0007. Down The Road Apiece (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.12) * S0008. Don't Stay Out All Night (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.30) * S0009. I Ain't Got You (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.00) * S0010. Johnny B. Goode (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) (2.24) * S0011. Reelin' And A Rockin' (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) * S0012. Bright Lights, Big City (Little Boy Blue & The Blue Boys) * 27 October 1962 Curly Clayton Sound Studios, Highbury, London, England. S0013. You Can't Judge A Book By The Cover (0.36) * S0014. Soon Forgotten * S0015. Close Together * 1963 11 March 1963 IBC Studios, London, England. S0016. Diddley Daddy (2.38) S0017. Road Runner (3.04) S0018. I Want To Be Loved I (2.02) S0019. -

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Invisible Man By Ralph Ellison Back Cover: Winner of the National Book Award for fiction. Acclaimed by a 1965 Book Week poll of 200 prominent authors, critics, and editors as "the most distinguished single work published in the last twenty years." Unlike any novel you've ever read, this is a richly comic, deeply tragic, and profoundly soul-searching story of one young Negro's baffling experiences on the road to self-discovery. From the bizarre encounter with the white trustee that results in his expulsion from a Southern college to its powerful culmination in New York's Harlem, his story moves with a relentless drive: -- the nightmarish job in a paint factory -- the bitter disillusionment with the "Brotherhood" and its policy of betrayal -- the violent climax when screaming tensions are released in a terrifying race riot. This brilliant, monumental novel is a triumph of storytelling. It reveals profound insight into every man's struggle to find his true self. "Tough, brutal, sensational. it blazes with authentic talent." -- New York Times "A work of extraordinary intensity -- powerfully imagined and written with a savage, wryly humorous gusto." -- The Atlantic Monthly "A stunning blockbuster of a book that will floor and flabbergast some people, bedevil and intrigue others, and keep everybody reading right through to its explosive end." -- Langston Hughes "Ellison writes at a white heat, but a heat which he manipulates like a veteran." -- Chicago Sun-Times TO IDA COPYRIGHT, 1947, 1948, 1952, BY RALPH ELLISON All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. For information address Random House, Inc., 457 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10022. -

The Rolling Stones Complete Recording Sessions 1962 - 2021 Martin Elliott Live Tracks in Date Order Index

THE ROLLING STONES COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1962 - 2021 MARTIN ELLIOTT LIVE TRACKS IN DATE ORDER INDEX All officially released live, and significant live tracks are listed. * Indicates the track has not been released officially. The number following in brackets is where to find the entry in the 2012 book should it have changed. A new entry following the book release will not have a number in brackets. 1964 7 February 1964 – ABC Elstree TV Studios, London, England. L0001. I Wanna Be Your Man (1.42) L0002. You Better Move On (2.40) 19 March 1964 - Camden Theatre, London, England. L0003. Route 66 (2.30) (91) L0004. Cops And Robbers (3.43) (92) L0005. You Better Move On (2.45) (93) L0006. Mona (2.57) (94) 10 April 1964 - Playhouse Theatre, London, England. L0007. Not Fade Away (2.04) * (95) L0008. High Heeled Sneakers (1.56) (96) L0009. Little By Little (2.30) (97) L0010. I Just Want To Make Love To You (2.16) (98) L0011. I'm Moving On (2.06) (99) 26 April 1964 - NME Poll Winners Concert, Empire Pool Wembley, London, England. L0012. Not Fade Away (2.01) (109) L0013. I Just Want To Make Love To You (2.19) (110) L0014. I'm Alright (2.07) (111) 27 April 1964 (Show One) - The Royal Albert Hall, London, England. L0015. Walking The Dog * L0016. You Can Make It If You Try * L0017. Beautiful Delilah * (2.14) (84) 27 April 1964 (Show Two) - The Royal Albert Hall, London, England. L0018. Not Fade Away * (112) L0019. High Heeled Sneakers * (113) L0020. -

Literalines 1999

'•, Y~,;,;., l \~ ~ ~· ·~, ~· :~~~.. LITERALINES VOLUME VI SPRING 1999 LITERALINES FACULTY EDITORIAL BOARD Mohammed Ansari Dennis Orwin Carol Austin Lisa Siefker Terry Dibble Rob Stilwell George Granholt Howard Wills Nancy McGill Katherine Wills FACULTY ADVISOR Judy Spector STUDENT PRODUCTION STAFF Laura Jordan, Ellen Kirk, Angie Richart, Debbie Sexton, and Dana Turnbow THE LITERALINES FACULTY EDITORIAL BOARD assembled and staring at a blank screell in pursuit ofperspective and inspiration. Uteralines, the IUPU Columbus Magazine of the Arts, is published in the spring of each year. ©Copyright 1999, first serial rights reserved. VOL. VI IN MEMORY OF DAVID SANCHEZ AND BERNARD RICHART Cover Art: "Perspectives," David Sanchez, 1970-1998. - CONTENTS Photo: Angels Sandy Rilenge .............................................................................................. 4 Angels in the Graveyard Laurie Rude ...........................................................· ...................................... 5 The Dis-Ease Ann Kristin Sanchez .................................................................................... 6 Restless Nights Arvilla Ater ................................................................................................. 7 Heaven and Hell Angie Richart .............................................................................................. 8 Drawing: Country Scene David Sanchez ........................................................................................... 1I Notes to Myself Arvilla Ater .............................................................................................. -

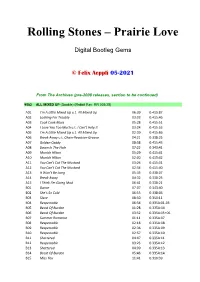

Digital Bootleg Gems

Rolling Stones – Prairie Love Digital Bootleg Gems © Felix Aeppli 05-2021 From The Archives (pre-2008 releases, section to be continued) 9582 ALL MIXED UP (Double) (Rabbit Rec. RR 024/25) A01 I’m A Little Mixed Up u.t. All Mixed Up 06:39 0.415:87 A02 Looking For Trouble 03:03 0.415:46 A03 Cook Cook Blues 05:28 0.415:51 A04 I Love You Too Much u.t. I Can’t Help It 03:24 0.415:53 A05 I’m A Little Mixed Up u.t. All Mixed Up 02:39 0.415:86 A06 Break Away u.t. Chain-Reaction-Groove 04:21 0.338:25 A07 Golden Caddy 08:58 0.415:43 A08 Down In The Hole 07:22 0.343:41 A09 Munich Hilton 05:29 0.415:41 A10 Munich Hilton 02:00 0.415:42 A11 You Can’t Cut The Mustard 03:26 0.415:31 A12 You Can’t Cut The Mustard 02:54 0.415:40 A13 It Won’t Be Long 05:33 0.338:07 A14 Break Away 04:32 0.338:25 A15 I Think I’m Going Mad 06:41 0.338:21 B01 Dance 07:07 0.343:40 B02 She’s So Cold 06:55 0.338:06 B03 Slave 08:50 0.350:11 B04 Respectable 06:54 0.335A:01-03 B05 Beast Of Burden 01:28 0.335A:04 B06 Beast Of Burden 03:52 0.335A:05+06 B07 Summer Romance 01:11 0.335A:07 B08 Respectable 02:18 0.335A:08 B09 Respectable 02:36 0.335A:09 B10 Respectable 02:57 0.335A:10 B11 Shattered 04:47 0.335A:11 B12 Respectable 03:23 0.335A:12 B13 Shattered 04:09 0.335A:13 B14 Beast Of Burden 05:46 0.335A:14 B15 Miss You 11:41 0.310:39 9592 CHAINSAW - UNDERCOVER OUTTAKES VOL. -

Trouble Songs

trouble songs Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-proft press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afoat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t fnd a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la open-access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) trouble songs. Copyright © 2018 by Jef T. Johnson. Tis work carries a Cre- ative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and trans- formation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2018 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-44-8 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-45-5 (ePDF) lccn: 2018930421 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Book design: Vincent W.J. -

Rolling Stones - Connection

Rolling Stones - Connection © Felix Aeppli 2021-03-29 Update Part 1 FULLY FINISHED STUDIO OUTTAKES VOL. 1.2.3 (Black Frisco Rec. BFR 101-103) Year Length TUG Entry Comments CD 1, VOLUME 1 (TIME 79:20) 01. NOBODY'S PERFECT 1985 04:07 0.432:101 New title 02. TROUBLE’S A COMING 1979 04:46 0.338:32 New title 03. DREAMS TO REMEMBER 1982 07:45 0.415:118 New title 04. DON’T LIE TO ME 1985 02:10 0.432:102 05. FIJI JIM 1978 03:43 0.311:67 06. ELIZA UPCHINK 1982 04:41 0.415:119 07. DEEP LOVE 1985 03:47 0.432:100 08. SHE’S DOING HER THING 1967 03:05 0.141:52 New title 09. PUTTY IN YOUR HANDS 1985 03:09 0.432:103 Finally out! 10. BIG TRUFF [u.t. DOG SHIT] 1982 06:09 0.415:120 New title 11. 20 NIL 1997 05:45 0.650:68 New title 12. TELL HER HOW IT IS 1970 04:07 0.188B:20 New title 13. (YOU BETTER) STOP THAT 1982 02:49 0.415:121 14. SCARLET 2020 03:39 1.284:7 15. WALK WITH ME WENDY 1970 04:07 0.188B:21 New title 16. NEVER MAKE YOU CRY 1978 04:32 0.311:68 17. PART OF THE NIGHT 1982 05:39 0.415:122 18. LOW DOWN 1997 05:12 0.650:67 CD 2, VOLUME 2 (TIME 74:32) 01. IT’S A LIE 1979 04:22 0.343:66 02.