The Fisheries of Central Visayas, Philippines: Status and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 Projects

Annual Infrastructure Program Revisions Flag: (D)elisted; (M)odified; (R)ealigned; (T)erminated Operating Unit/ Revisions UACS PAP Project Component Decsription Project Component ID Type of Work Target Unit Target Allocation Implementing Office Flag Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 projects GAA 2016 MFO-1 7,959,170,000 202 projects Bohol 1st District Engineering Office 1,498,045,000 69 projects BOHOL (FIRST DISTRICT) Network Development - Off-Carriageway Improvement including drainage 165003015600115 Tagbilaran East Rd (Tagbilaran-Jagna) - K0248+000 - K0248+412, P00003472VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,609 62,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0248+950 - K0249+696, K0253+000 - K0253+215, K0253+880 - Improvement: Shoulder K0254+701 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Paving / Construction Construction 165003015600117 Tagbilaran North Rd (Tagbilaran-Jetafe Sect) - K0026+000 - K0027+ P00003476VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,828 49,500,000 Bohol 1st District 540, K0027+850 - K0028+560 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office 165003015600225 Jct (TNR) Cortes-Balilihan-Catigbian-Macaas Rd - K0009+-130 - P00003653VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 9,777 91,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0010+382, K0020+000 - K0021+745 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 165003015600226 Jct. (TNR) Maribojoc-Antequera-Catagbacan (Loon) - K0017+445 - P00015037VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 3,141 32,000,000 Bohol 1st District K0018+495 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office Construction and Maintenance of Bridges along National Roads - Retrofitting/ Strengthening of Permanent Bridges 165003016100100 Camayaan Br. -

Icc-Wcf-Competition-Negros-Oriental-Cci-Philippines.Pdf

World Chambers Competition Best job creation and business development project Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry The Philippines FINALIST I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry Inc. (NOCCI), being the only recognized voice of business in the Province of Negros Oriental, Philippines, developed the TIP PROJECT or the TRADE TOURISM and INVESTMENT PROMOTION ("TIP" for short) PROJECT to support its mission in conducting trade, tourism and investment promotion, business development activities and enhancement of the business environment of the Province of Negros Oriental. The TIP Project was conceptualized during the last quarter of 2013 and was launched in January, 2014 as the banner project of the Chamber to support its new advocacy for inclusive growth and local economic development through job creation and investment promotion. The banner project was coined from the word “tip” - which means giving sound business advice or sharing relevant information and expertise to all investors, businessmen, local government officials and development partners. The TIP Project was also conceptualized to highlight the significant role and contribution of NOCCI as a champion for local economic development and as a banner project of the Chamber to celebrate its Silver 25th Anniversary by December, 2016. For two years, from January, 2015 to December, 2016, NOCCI worked closely with its various partners in local economic development like the Provincial Government, Local Government Units (LGUs), National Government Agencies (NGAs), Non- Government Organizations (NGOs), Industry Associations and international funding agencies in implementing its various job creation programs and investment promotion activities to market Negros Oriental as an ideal investment/business destination for tourism, retirement, retail, business process outsourcing, power/energy and agro-industrial projects. -

Blanchard's - Lang's Sporting Auction

Blanchard's - Lang's Sporting Auction 1891 Morley-Potsdam Rd Potsdam, NY 13676 Preview: Friday, September 25 – 5:00-7:00pm, Saturday, September 26 - 8:00-9:00am Auction Start: Saturday, September 26 - 9:00am 1 3 Art of Angling Journals 37 3 Boxed Heddon Lures 2 1 Creel and 1 Knife 38 3 Boxed South Bend Lures 3 4 Brass Trout Reels 39 3 Boxed Barracuda Lures 4 5 Vintage Fly Reels 40 5 Denton Trout & Salmon Prints 5 5 Casting Reels 41 5 Atlantic Salmon Journals, 1 Fortune Magazine 6 3 Meisselbach Featherlight Fly Reels 42 3 Hunting/Trapping Paper Items 7 2 Surf Casting Reels 43 4 Tackle Catalogs 8 3 Early Trout Reels 44 6 Early Outdoor Magazines 9 1 Early English Salmon Reel w/ Leather Case 45 10 Early National Sportsmans Magazines 10 4" Hardy Uniqua Salmon Reel 46 7 Early Magazines 11 4 1/2 J. Vom Hofe Salmon Reel 47 7 Early Magazines 12 2 J. Vom Hofe Casting Reels 48 3 Angling Books 13 2 J.W. Young Fly Reels 49 2 Angling Books and 1 Fosters Diary 14 2 Early Saltwater Reels 50 1 Trout Painted Wood Box, Framed Tri-Fold Photos 15 5 Boxed Fly Reels 51 Assorted Jungle Cock Feathers 16 1 Boxed Penn #99 Silver Beach Reel 52 1 Wallet w/ Flies, 3 Carded Flies, Foss Streamers 17 4 Casting Reels and Pennell Reel Case 53 1 Framed Fish Print and 2 Fish Decoys 18 3 Wooden Trolling Reels 54 4 Vintage Surf Casting Reels 19 3 Meisselbach Expert Fly Reels 55 3 Surf Reels 20 3 Meisselbach Symploreels 56 5 Classic Casting Reels 21 7 1/2' Fenwick Boron X 5wt Fly Rod 57 4 Meisselbach Reels 22 3/2 Bamboo Salmon Rod in Formed Case 58 5 Meisselbach Tri-Part Reels -

Constructed Wetland for a Peri-Urban Housing Area Bayawan City, Philippines

Case study of sustainable sanitation projects Constructed wetland for a peri-urban housing area Bayawan City, Philippines biow aste faeces/manure urine greywater rainwater Pour-flush toilets (to septic tank) Small-bore sewer system collection Septic tank effluent treated in constructed wetland treatment Treated wastewater for irrigation reuse Fig. 1: Project location Fig. 2: Applied sanitation components in this project 1 General data 2 Objective and motivation of the project The objectives of the project were to : Type of project: • Protect coastal waters from pollution with domestic Peri-urban upgrading of a settlement; domestic wastewater. wastewater treatment with constructed wetland (or reed • Protect the health of the local residents through improved bed) housing with safe sanitation and wastewater treatment facilities. Project period: • Demonstrate constructed wetland technology. Bayawan Start of planning: Feb 2005 was the first city in the Philippines that built a constructed Start of construction: June 2005 wetland for domestic wastewater treatment. Therefore, Start of operation: Sept 2006 (and ongoing) one of the objectives was to use it as a pilot and Project scale: demonstration project for other communities. Relocation housing area for 676 houses (average household size of 5 people, although some houses contain more than one family); design figure: 3380 people. 3 Location and conditions Total construction cost for the constructed wetland was Bayawan City is located in the south-west of Negros Island, about EUR 160,000 including consultancy and labour. covering a total land area of about 70,000 hectares and with Address of project location: a population of about 113,000. The project is located in a Fishermen’s Gawad Kalinga Village, Barangay Villareal, peri-urban area of Bayawan, which has been used to resettle Bayawan City, Philippines families that lived along the coast in informal settlements and had no access to safe water supply and sanitation facilities. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

SOIL Ph MAP N N a H C Bogo City N O CAMOT ES SEA CA a ( Key Rice Areas ) IL

Sheet 1 of 2 124°0' 124°30' 124°0' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S Car ig ar a Bay D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R IIC U L T U R E Madridejos BURE AU OF SOILS AND Daanbantayan WAT ER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Roa d Cor. Visa yas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City Bantayan Province of Santa Fe V IS A Y A N S E A Leyte Hagnaya Bay Medellin E L San Remigio SOIL pH MAP N N A H C Bogo City N O CAMOT ES SEA CA A ( Key Rice Areas ) IL 11°0' 11°0' A S Port Bello PROVINCE OF CEBU U N C Orm oc Bay IO N P Tabogon A S S Tabogon Bay SCALE 1:300,000 2 0 2 4 6 8 Borbon Tabuelan Kilom eter s Pilar Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : PRS 1992 Sogod DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative Tuburan Catmon Province of Negros Occidental San Francisco LOCATION MA P Poro Tudela T I A R T S Agusan Del S ur N Carmen O Dawis Norte Ñ A Asturias T CAMOT ES SEA Leyte Danao City Balamban 11° LU Z O N 15° Negros Compostela Occi denta l U B E Sheet1 C F O Liloan E Toledo City C Consolacion N I V 10° Mandaue City O R 10° P Magellan Bay VIS AYAS CEBU CITY Bohol Lapu-Lapu City Pinamungajan Minglanilla Dumlog Cordova M IN DA NA O 11°30' 11°30' 5° Aloguinsan Talisay 124° 120° 125° ColonNaga T San Isidro I San Fernando A R T S T I L A O R H T O S Barili B N Carcar O Ñ A T Dumanjug Sibonga Ronda 10°0' 10°0' Alcantara Moalboal Cabulao Bay Badian Bay Argao Badian Province of Bohol Cogton Bay T Dalaguete I A R T S Alegria L O H O Alcoy B Legaspi ( ilamlang) Maribojoc Bay Guin dulm an Bay Malabuyoc Boljoon Madridejos Ginatilan Samboan Oslob B O H O L S E A PROVINCE OF CEBU SCALE 1:1,000,000 T 0 2 4 8 12 16 A Ñ T O Kilo m e te r s A N Ñ S O T N Daanbantayan R Santander S A T I Prov. -

Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing

The American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing FALL 2000 VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 Time Flies Arhor-Hoch T ' s M I D -AU G u s T as I write this, and for once I don't have the ouvortunitvL L to revrint some of the articles from that series. to imagine what fall feels like-today it's here. The tempera- and I intend to do so from time to time. In this issue, we're Itures have dropped, and this morning it feels like late pleased to include "Fly Lines and Lineage." Betts argues that September. As I prepare for a canoe camping trip, I wonder if the evolution of the forms of dry and wet flies is a direct I'll be warm enough. This Vermont summer couldn't have been response to changes in tackle. As fly line changed, the rods more different from the one our western readers had. needed to cast the line changed, and new casting techniques So fall is here, and in keeping with the anticipation that had to be learned: all of which meant that flies cast such a dis- tends to accompany that initial chill in the air, this issue brings tance had to be designed to either float on their own or to sink you news of some of the exciting happenings at the Museum appropriately. Betts focuses the bulk of his discussion on fly over the last year. After months of preparation, our traveling line and wet flies. His article begins on page 17. -

LIST of PROJECTS ISSUED CEASE and DESIST ORDER and CDO LIFTED( 2001-2019) As of May 2019 CDO

HOUSING AND LAND USE REGULATORY BOARD Regional Field Office - Central Visayas Region LIST OF PROJECTS ISSUED CEASE AND DESIST ORDER and CDO LIFTED( 2001-2019) As of May 2019 CDO PROJECT NAME OWNER/DEVELOPER LOCATION DATE REASON FOR CDO CDO LIFTED 1 Failure to comply of the SHC ATHECOR DEVELOPMENT 88 SUMMER BREEZE project under RA 7279 as CORP. Pit-os, Cebu City 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 2 . Failure to comply of the SHC 888 ACACIA PROJECT PRIMARY HOMES, INC. project under RA 7279 as Acacia St., Capitol Site, cebu City 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 3 A & B Phase III Sps. Glen & Divina Andales Cogon, Bogo, Cebu 3/12/2002 Incomplete development 4 . Failure to comply of the SHC DAMARU PROPERTY ADAMAH HOMES NORTH project under RA 7279 as VENTURES CORP. Jugan, Consolacion, cebu 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 5 Adolfo Homes Subdivision Adolfo Villegas San Isidro, Tanjay City, Negros O 7/5/2005 Incomplete development 7 Aduna Beach Villas Aduna Commerial Estate Guinsay, Danao City 6/22/2015 No 20% SHC Corp 8 Agripina Homes Subd. Napoleon De la Torre Guinobotan, Trinidad, Bohol 9/8/2010 Incomplete development 9 . AE INTERNATIONAL Failure to comply of the SHC ALBERLYN WEST BOX HILL CONSTRUCTION AND project under RA 7279 as RESIDENCES DEVELOPMENT amended by RA 10884 CORPORATION Mohon, Talisay City 21/12/2018 10 Almiya Subd Aboitizland, Inc Canduman, Mandaue City 2/10/2015 No CR/LS of SHC/No BL Approved plans 11 Anami Homes Subd (EH) Softouch Property Dev Basak, Lapu-Lapu City 04/05/19 Incomplete dev 12 Anami Homes Subd (SH) Softouch Property -

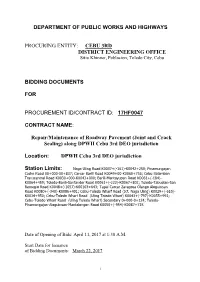

Department of Public Works and Highways Procuring Entity: Cebu 3Rd District Engineering Office Bidding Documents for Procuremen

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS PROCURING ENTITY: CEBU 3RD DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE Sitio Khinner, Poblacion, Toledo City, Cebu BIDDING DOCUMENTS FOR PROCUREMENT ID/CONTRACT ID: 17HF0047 CONTRACT NAME: Repair/Maintenance of Roadway Pavement (Joint and Crack Sealing) along DPWH Cebu 3rd DEO jurisdiction Location: DPWH Cebu 3rd DEO jurisdiction Station Limits: Naga Uling Road K0037+(-161)-K0042+250; Pinamungajan Cadre Road 00+000-00+837; Carcar Barili Road K0049+00-K0060+756; Cebu Balamban Transcentral Road K0030+000-K0043+000; Barili-Mantayupan Road K0061+(-184)- K0064+459; Toledo-Barili-Santander Road K0061+(-222)-K0067+802; Toledo-Tabuelan-San Remegio Road K0048+(-1057)-K00103+643; Tapal Carcar Zaragosa Olango Aloguinsan Road K0080+(-340)-K0086+401; Cebu-Toledo Wharf Road (Jct. Naga Uling) K0029+(-610)- K0034+950; Cebu-Toledo Wharf Road (Uling Toledo Wharf) K0043+(-797)-K0055+991; Cebu-Toledo Wharf Road (Uling Toledo Wharf) Secondary 0+000-0+124; Toledo- Pinamungajan-Aloguinsan-Mantalongon Road K0050+(-954)-K0087+715. Date of Opening of Bids: April 11, 2017 at 1:30 A.M. Start Date for Issuance of Bidding Documents: March 22, 2017 1 Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Contract ID: 17HF0047 Contract Name: Repair/Maintenance of Roadway Pavement (Joint and Crack Sealing) along DPWH Cebu 3rd DEO jurisdiction Location of the Contract: DPWH Cebu 3rd DEO jurisdiction Station Limts: Naga Uling Road K0037+(-161)-K0042+250; Pinamungajan Cadre Road 00+000-00+837; Carcar Barili Road K0049+00-K0060+756; Cebu Balamban Transcentral Road K0030+000-K0043+000; Barili-Mantayupan Road K0061+(-184)-K0064+459; Toledo-Barili-Santander Road K0061+(-222)- K0067+802; Toledo-Tabuelan-San Remegio Road K0048+(-1057)-K00103+643; Tapal Carcar Zaragosa Olango Aloguinsan Road K0080+(-340)-K0086+401; Cebu-Toledo Wharf Road (Jct. -

Newletter No30 AUG 2017 Draft 5

DISPATCH CEBU ISSUE NO. 30 AUGUST 2017 Air Juan holds press launch, adds 2 new routes from CEB Departure Flight Crew of Cebu-Maasin Local airline Air Juan (AO) held a press launch at Mactan Cebu International Airport last August 1. Air Juan President Mr. John Gutierrez, Marketing Head Mr. Paolo Misa and seaplane pilot Mr. Mark Griffin answered questions from the media, together with GMCAC Chief Commercial Advisor Mr. Ravi Saravu. Air Juan does not compete with the bigger airlines, rather it connects the smaller islands. They want to be known for their seaplanes, which they also plan to operate in Cebu soon. Cake Cutting Ceremony Q&A with Press L-R: Air Juan Seaplane Pilot Mr. Mark Griffin, Air Juan President Mr. John Gutierrez, GMCAC Chief Commercial Advisor Mr. Ravi Saravu, Air Juan Marketing Head Mr. Paolo Misa. The press event coincided with the maiden flight of its new route from Cebu to Maasin, Leyte. Air Juan also launched Cebu to Sipalay in Negros on August 3. They now operate 6 routes from Cebu, including the tourist destinations of Tagbilaran (Bohol), Siquijor, Bantayan Island and Biliran. Departure Water Cannon Salute of 1st Commercial Flight (Cebu-Caticlan) PAL introduces new Q400 NG aircraft Mactan Cebu International Airport welcomed the arrival of Philippine Airlines’ new Bombardier Q400 Next Generation aircraft last August 1. PAL Express President Mr. Bonifacio Sam and Bombardier Director for Asia Pacific Sales Mr. Aman Kochher, among other VIP guests and media, graced the sendoff ceremony of the aircraft’s 1st commercial flight bound for Caticlan (Boracay). -

Or Negros Oriental

CITY CANLAON CITY LAKE BALINSASAYAO KANLAON VOLCANO VALLEHERMOSO Sibulan - The two inland bodies of Canlaon City - is the most imposing water amid lush tropical forests, with landmark in Negros Island and one of dense canopies, cool and refreshing the most active volcanoes in the air, crystal clear mineral waters with Philippines. At 2,435 meters above sea brushes and grasses in all hues of level, Mt. Kanlaon has the highest peak in Central Philippines. green. Balinsasayaw and Danao are GUIHULNGAN CITY 1,000 meters above sea level and are located 20 kilometers west of the LA LIBERTAD municipality of Sibulan. JIMALALUD TAYASAN AYUNGON MABINAY BINDOY MANJUYOD BAIS CITY TANJAY OLDEST TREE BAYAWAN CITY AMLAN Canlaon City - reportedly the oldest BASAY tree in the Philipines, this huge PAMPLONA SAN JOSE balete tree is estimated to be more NILUDHAN FALLS than a thousand years old. SIBULAN Sitio Niludhan, Barangay Dawis, STA. CATALINA DUMAGUETE Bayawan City - this towering cascade is CITY located near a main road. TAÑON STRAIT BACONG ZAMBOANGUITA Bais City - Bais is popular for its - dolphin and whale-watching activities. The months of May and September are ideal months SIATON for this activity where one can get a one-of-a kind experience PANDALIHAN CAVE with the sea’s very friendly and intelligent creatures. Mabinay - One of the hundred listed caves in Mabinay, it has huge caverns, where stalactites and stalagmites APO ISLAND abound. The cave is accessible by foot and has Dauin - An internationally- an open ceiling at the opposite acclaimed dive site with end. spectacular coral gardens and a cornucopia of marine life; accessible by pumpboat from Zamboanguita. -

PESO-Region 7

REGION VII – PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT SERVICE OFFICES PROVINCE PESO Office Classification Address Contact number Fax number E-mail address PESO Manager Local Chief Executive Provincial Capitol , (032)2535710/2556 [email protected]/mathe Cebu Province Provincial Cebu 235 2548842 [email protected] Mathea M. Baguia Hon. Gwendolyn Garcia Municipal Hall, Alcantara, (032)4735587/4735 Alcantara Municipality Cebu 664 (032)4739199 Teresita Dinolan Hon. Prudencio Barino, Jr. Municipal Hall, (032)4839183/4839 Ferdinand Edward Alcoy Municipality Alcoy, Cebu 184 4839183 [email protected] Mercado Hon. Nicomedes A. de los Santos Municipal Alegria Municipality Hall, Alegria, Cebu (032)4768125 Rey E. Peque Hon. Emelita Guisadio Municipal Hall, Aloquinsan, (032)4699034 Aloquinsan Municipality Cebu loc.18 (032)4699034 loc.18 Nacianzino A.Manigos Hon. Augustus CeasarMoreno Municipal (032)3677111/3677 (032)3677430 / Argao Municipality Hall, Argao, Cebu 430 4858011 [email protected] Geymar N. Pamat Hon. Edsel L. Galeos Municipal Hall, (032)4649042/4649 Asturias Municipality Asturias, Cebu 172 loc 104 [email protected] Mustiola B. Aventuna Hon. Allan L. Adlawan Municipal (032)4759118/4755 [email protected] Badian Municipality Hall, Badian, Cebu 533 4759118 m Anecita A. Bruce Hon. Robburt Librando Municipal Hall, Balamban, (032)4650315/9278 Balamban Municipality Cebu 127782 (032)3332190 / Merlita P. Milan Hon. Ace Stefan V.Binghay Municipal Hall, Bantayan, melitanegapatan@yahoo. Bantayan Municipality Cebu (032)3525247 3525190 / 4609028 com Melita Negapatan Hon. Ian Escario Municipal (032)4709007/ Barili Municipality Hall, Barili, Cebu 4709008 loc. 130 4709006 [email protected] Wilijado Carreon Hon. Teresito P. Mariñas (032)2512016/2512 City Hall, Bogo, 001/ Bogo City City Cebu 906464033 [email protected] Elvira Cueva Hon.