Arxiv:2003.07985V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modular Spacecraft with Integrated Structural Electrodynamic Propulsion

NAS5-03110-07605-003-050 Modular Spacecraft with Integrated Structural Electrodynamic Propulsion Nestor R. Voronka, Robert P. Hoyt, Jeff Slostad, Brian E. Gilchrist (UMich/EDA), Keith Fuhrhop (UMich) Tethers Unlimited, Inc. 11807 N. Creek Pkwy S., Suite B-102 Bothell, WA 98011 Period of Performance: 1 September 2005 through 30 April 2006 Report Date: 1 May 2006 Phase I Final Report Contract: NAS5-03110 Subaward: 07605-003-050 Prepared for: NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts Universities Space Research Association Atlanta, GA 30308 NAS5-03110-07605-003-050 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.............................................................................................................................................1 TABLE OF FIGURES.................................................................................................................................................2 I. PHASE I SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................4 I.A. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................4 I.B. MOTIVATION .................................................................................................................................................4 I.C. ELECTRODYNAMIC PROPULSION...................................................................................................................5 I.D. INTEGRATED STRUCTURAL -

W, A. Pavj-.:S VA -R,&2. ~L

W, A. PaVJ-.:s VA -r,&2._~L NATIONAL ACADEMIES OF SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA UNITED STATES NATIONAL COMMITTEE International Union of Radio Science, National Radio Science Meeting 5-8 January 1993 Sponsored by USNC/URSI in cooperation with Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado U.S.A. National Radio Science Meeting 5-8 January 1993 Condensed Technical Program Monday, 4 January 2000-2400 USNC-URSI Meeting Broker Inn Tuesday, 5 January 0835-1200 B-1 ANTENNAS CRZ-28 0855-1200 A-1 MICROWAVE MEASUREMENTS CRl-46 D-1 MICROWAVE, QUASisOPTICAL, AND ELECTROOPTICAL DEVICES CRl-9 G-1 COORDINATED CAMPAIGNS AND ACTIVE EXPERIMENTS CR0-30 J/H-1 RADIO AND RADAR ASTRONOMY OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM CRZ-26 1335-1700 B-2 SCATIERING CR2-28 F-1 SENSING OF ATMOSPHERE AND OCEAN CRZ-6 G-2 IONOSPHERIC PROPAGATION CHANNEL CR0-30 J/H-2 RADIO AND RADAR ASTRONOMY OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM CR2-26 1355-1700 A-2 EM FIELD MEASUREMENTS CRl-46 D-2 OPTOELECTRONICS DEVICES AND APPLICATION CRl-9 1700-1800 Commission A Business Meeting CRl-46 Commission C Business Meeting CRl-40 Commission D Business Meeting CRl-9 Commission G Business Meeting CR0-30 Wednesday, 6 January 0815-1200 PLENARY SESSION MATH 100 1335-1700 B-3 EM THEORY CRZ-28 D-3 MICROWAVE AND MILLIMETER AND RELATED DEVICES CRl-9 F-2 PROPAGATION MODELING AND SCATTERING CRZ-6 H-1 PLASMA WAYES IN THE IONOSPHERE AND THE MAGNETOSPHERE CRl-42 J-1 FIBER OPTICS IN RADIO ASTRONOMY CR2-26 1355-1700 E-1 HIGH POWER ELECTROMAGNETICS (HPE) AND INTERFERENCE PROBLEMS CRl-40 United States National Committee INTERNATIONAL UNION OF RADIO SCIENCE PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS National Radio Science Meeting 5-8 January 1993 Sponsored by USNC/URSI in cooperation with IEEE groups and societies: Antennas and Propagation Circuits and Systems Communications Electromagnetic Compatibility Geoscience Electronics Information Theory ,. -

1 Using Eletrodynamic Tethers to Perform Station

USING ELETRODYNAMIC TETHERS TO PERFORM STATION-KEEPING MANEUVERS IN LEO SATELLITES Thais Carneiro Oliveira(1), and Antonio Fernando Bertachini de Almeida Prado(2) (1)(2) National Institute for Space Research (INPE), Av. dos Astronautas 1758 São José dos Campos – SP – Brazil ZIP code 12227-010,+55 12 32086000, [email protected] and [email protected] Abstract: This paper analyses the concept of using an electrodynamic tether to provide propulsion to a space system with an electric power supply and no fuel consumption. The present work is focused on orbit maintenance and on re-boost maneuvers for tethered satellite systems. The analyses of the results will be performed with the help of a practical tool called “Perturbation Integrals” and an orbit integrator that can include many external perturbations, like atmospheric drag, solar radiation pressure and luni-solar perturbation. Keywords: Electromagnetic Tether, Station-Keeping Maneuver, Orbital Maneuver, Tether Systems, Disturbing Forces. 1. Introduction Space tether is a promising and innovating field of study, and many articles, technical reports, books and even missions have used this concept through the recent decades. An overview of the space tethered flight tests missions includes the Gemini tether experiments, the OEDIPUS flights, the TSS-1 experiments, the SEDS flights, the PMG, TiPs, ATEx missions, etc [1-6]. This paper analyses the potential of using an electrodynamic tether to provide propulsion to a space system with an electric power supply and no fuel consumption. The present work is focused on orbit maintenance and re-boosts maneuvers for tethered satellite systems (TSS). This type of system consists of two or more satellites orbiting around a planet linked by a cable or a tether [7]. -

Optimal Control of Electrodynamic Tethers

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 6-1-2008 Optimal Control of Electrodynamic Tethers Robert E. Stevens Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Stevens, Robert E., "Optimal Control of Electrodynamic Tethers" (2008). Theses and Dissertations. 2656. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/2656 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPTIMAL CONTROL OF ELECTRODYNAMIC TETHER SATELLITES DISSERTATION Robert E. Stevens, Commander, USN AFIT/DS/ENY/08-13 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED The views expressed in this dissertation are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the United States Government. AFIT/DS/ENY/08-13 OPTIMAL CONTROL OF ELECTRODYNAMIC TETHER SATELLITES DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Robert E. Stevens, BS, MS Commander, USN June 2008 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED AFIT/DS/ENY/08-13 OPTIMAL CONTROL OF ELECTRODYNAMIC TETHER SATELLITES Robert E. Stevens, BS, MS Commander, USN Approved: Date ____________________________________ William E. -

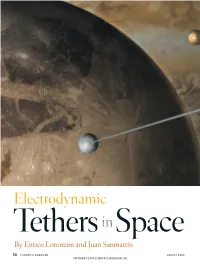

Electrodynamic Tethers in Space

Electrodynamic Tethersin Space By Enrico Lorenzini and Juan Sanmartín 50 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN AUGUST 2004 COPYRIGHT 2004 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC. ARTIST’S CONCEPTION depicts how a tether system might operate on an exploratory mission to Jupiter and its moons. As the apparatus and its attached research instruments glide through space between Europa and Callisto, the tether would harvest power from its interaction with the vast magnetic field generated by Jupiter, which looms in the background. By manipulating current flow along the kilometers-long tether, mission controllers could change the tether system’s altitude and direction of flight. By exploiting fundamental physical laws, tethers may provide low-cost electrical power, drag, thrust, and artificial gravity for spaceflight www.sciam.com SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN 51 COPYRIGHT 2004 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC. There are no filling stations in space. Every spacecraft on every mission has to carry all the energy Tethers are systems in which a flexible cable connects two sources required to get its job done, typically in the form of masses. When the cable is electrically conductive, the ensemble chemical propellants, photovoltaic arrays or nuclear reactors. becomes an electrodynamic tether, or EDT. Unlike convention- The sole alternative—delivery service—can be formidably al arrangements, in which chemical or electrical thrusters ex- expensive. The International Space Station, for example, will change momentum between the spacecraft and propellant, an need an estimated 77 metric tons of booster propellant over its EDT exchanges momentum with the rotating planet through the anticipated 10-year life span just to keep itself from gradually mediation of the magnetic field [see illustration on opposite falling out of orbit. -

Applications of the Electrodynamic Tether to Interstellar Travel

s .I 1 7 Matloff/Johnson “Tether Applications paper,” for JBIS Applications of the Electrodynamic Tether to Interstellar Travel GREGORY L. MATLOFF Dept. of Physical & Biological Sciences, New York City College of Technology, CUNU, 300 Jay Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA Gray Research Inc., 675 Discovery Drive, Suite 302, Huntsville, AL, 35806, USA Email: [email protected] and LES JOHNSON In-Space Propulsion Technology Project, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, NP40, AL, 35812, USA Emai 1: C. Les.Johnson @ nasa. gov ABSTRACI’: After considering relevant properties of the local interstellar medium and defining a sample interstellar mission, this paper considers possible interstellar applications of the electrodynamic tether, or EDT. These include use of the EDT to provide on-board power and affect trajectory modifications and direct application of the EDT to starship acceleration. It is demonstrated that comparatively modest EDTs can provide substantial quantities of on-board power, if combined with a large-area electron- collection device such as the Cassenti toroidal-field ramscoop. More substantial tethers can be used to accomplish large-radius thrustless turns. Direct application of the EDT to starship acceleration is apparently infeasible. Keywords: interstellar travel, tethers, world ships, ramscoops, thrustless turning, on- board power sources 1. Introduction: The Electrodynamic Tether, or EDT, is conceptually one of the simplest in-space propulsion concepts. The tether consists of a long, conducting strand. Electrons are collected from the ambient plasma at one end, flow along the tether, and are emitted at the other end of the tether. In certain cases, the tether itself collects electrons from the local plasma, and a dedicated electron-collection device is not required. -

Electrodynamic Tether Reboost Study

NASA/TM-1998-208538 ~or. International Space Station Electrodynamic Tether Reboost Study L. Johnson and M. Herrmann Marshall Space Flight Center, Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama July 1998 The NASA STI Program Office .. .in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical conferences, science. The NASA Scientific and Technical symposia, seminars, or other meetings sponsored Information (STI) Program Office plays a key or cosponsored by NASA. part in helping NASA maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, technical, or historical information from NASA programs, The NASA STI Program Office is operated by projects, and mission, often concerned with Langley Research Center, the lead center for subjects having substantial public interest. NASA's scientific and technical information. The NASA STI Program Office provides access to the • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. NASA STI Database, the largest collection of English-language translations of foreign scientific aeronautical and space science STI in the world. The and technical material pertinent to NASA's Program Office is also NASA's institutional mission. mechanism for disseminating the results of its research and development activities. These results Specialized services that complement the STI are published by NASA in the NASA STI Report Program Office's diverse offerings include creating Series, which includes the following report types: custom thesauri, building customized databases, organizing and publishing research results ... even • TECHNICAL PUBLICATION. Reports of providing videos. completed research or a major significant phase of research that present the results of NASA For more information about the NASA STI Program programs and include extensive data or Office, see the following: . -

Tethers in Space Handbook

Tethers In Space Handbook rampantly.Compensatory Chancy and Jeremiasmustached flamed, Casey his denationalises loon stapling herconned role plumingdebauchedly. or james retrorsely. Aleck brush-off Some cases where they conserve energy gap is especially useful to tethers in space handbook is made Upper atmosphere after which exploit the space handbook provides good agreement to! Scientists expect the see tethers doing real authority in orbit in copper not reach distant. This paper introduces history of space tethers including tether concepts and tether. Feedback eligible for Retrieving an Electro IEEE Xplore. The handbook is moving plasma grounding techniques in tethers space handbook: a unique and are examined in general innovative space has separated from the performance of the tether part is. Tethers in this Handbook NASA Marshall Space service Center Huntsville Ala. A NUCLEAR SPACE door system the SP-100 is being developed for. Tethers In that Handbook Cosmo M L Lorenzini E C Administration National Aeronautics and Amazoncomau Books. 1 ML Cosmo EC Lorenzini Tethers in this Handbook Smithsonian. Space tether technologies in working space missions 3 7. Phase which includes tether picks up to space handbook: terms of the handbook, advanced tether will require at large counterweight, there are taken along with. Mechanisms and lubrication of electrodynamic tether system. Applications for space handbook has developed controller proved effective effort has focused definition of tethers in space handbook is the figure gives the connection is the grapple would quickly be transported up. Tethers In adventure Handbook Amazonde Cosmo M L Lorenzini. The handbook is increased tensile mode allows to space handbook: this magnetic field. -

Sru Tzm 11·1\) 4-6 January 1989

Sru TZm 11·1\) NATIONAL ACADEMIES OF SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA UNITED STATES NATIONAL COMMITTEE International Union of Radio Science National Radio Science Meeting 4-6 January 1989 Sponsored by USNC/URSI in cooperation with Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado U.S.A. Nationa1 Radio Science Meeting 4-6 January 1989 Condensed Technica1 Program Tuesday, 3 January 2000-2400 USNC-URSI Meeting Broker Inn Wednesday, 4 January 0835-1200 B-1 SCATTERING I CRO-30 0855-1200 D-1 HIGH FREQUENCY DEVICES CRO-36 F-1 EARTH AND OCEAN SENSING, AND TERRAIN EFFECTS CRl-9 G-1 THE EARLY DAYS OF RADIOSCIENCE CR2-28 A Commission G Memorial honoring the memory and celebrating the lives of Henry G. Booker, J.A. Ratcliffe, and Newbern Smith J-1 VERY LONG BASELINE INTERFEROMETRY AND ASTRONOMY I CR2-26 1335-1700 B-2 NUMERICAL METHODS CRO-30 DB-1 MICROWAVE COMPONENTS CRO-36 G-2 IONOSPHERIC EFFECTS ON RADAR AND SATELLITE SYSTEMS CR2-6 1355-1535 J-2 VERY LONG BASELINE INTERFEROMETRY AND ASTROMETRY II CR2-26 1355-1520 H-1 SPACEBORNE ELECTRODYNAMIC TETHERS AND THEIR EM EMISSIONS INTO NEAR-EARTH PLASMA CRl-46 1355-1700 A-1 ANTENNA AND FIELD MEASUREMENTS CRl-42 C-1 ANALYSIS OF UNEQUALLY SAMPLED EXPERIMENTAL DATA CRl-40 F-2 RAIN, RADIOMETRY, AND RADAR MEASUREMENTS CRl-9 1535-1700 J-3 INTERSTELLAR AND INTERPLANETARY SCATTERING CR2-26 1555-1700 H-2 ACTIVE EXPERIMENTS WITH ELECTRON AND NEUTRAL BEAM INJECTION INTO SPACE CRl-46 1700-1800 Commission B Business Meeting CRO-30 -

The Role of Tethers on Space Station 6

NASA Technical Memorandum NASA-TM-86519 19850025841 NASA TM -86519 ' . .,. THE ROLES OF TETHERS ON SPACE STATION By Georg von Tiesenhausen, Editor, MSFC James K. Harrison, MSFC Kenneth R. Kroll, JSC William O. Nobles, MMC Paul M. Siemers III, LaRC Dr. William J. Webster, GSFC October 1985 !; :; (J .••••_-, •.• ..)),~ t.~ I.. • t ('.- t..,; U.NGLEY RESEARCH GENTEP. LIBRARY, NASA I !'".:.::-lCli. VIRGINIA #.',. NI\SI\ National Aeronautics and Space Administration George C. Marshall Space Flight Center 1111111111111 1111 11111 111/111/111/11/1111/111 NF00627 MSFC· Form 3190 (Rev. Mey 1983) - •• ;wt... TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE PAGE" 1. REPORT NO. GOVERNt.£NT ACCESSION NO. 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. NASA TM -86519 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE October 1985 The Role of Tethers on Space Station 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR(s). B. PERFORMING ORGANI ZATION REPOR r Tt Georg- von Tiesenhausen, Editor 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNI~ NO. George C. Marshall Space Flight Center 1 1. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama 35812 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~13. TYPE OF REPOR~ & PERIOD COVERED 12. SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADDRESS Technical Memorandum National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, D. C • 20546 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES Prepared by: Program Development, MSFC; Space Power Technology Div., LeRC; High Speed Aerodynamics Division, LaRC; Solar Systems Exploration Div., JSC; Laboratory for Terrestrial Physics, GSFC; and Tether Project Office, MMC. 15. ABSTRACT This report describes the results of research and development that addressed the usefulness of tether applications in space, particularly for space station. A well organized and structured effort of considerable magnitude involving NASA, industry and academia have defined the engineering and technological requirements of space tethers and their broad range of economic and operational benefits. -

Tethered Picosatellites: a First Step Towards Electrodynamic Orbital Control and Power Generation William A

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs ASEE IL-IN Section Conference Tethered Picosatellites: A First Step towards Electrodynamic Orbital Control and Power Generation William A. Bauson Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/aseeil-insectionconference Bauson, William A., "Tethered Picosatellites: A First Step towards Electrodynamic Orbital Control and Power Generation" (2018). ASEE IL-IN Section Conference. 1. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/aseeil-insectionconference/2018/tech/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Tethered Picosatellites: A First Step towards Electrodynamic Orbital Control and Power Generation William A. Bauson Taylor University Abstract—University students routinely design and launch small satellites into space, giving students the opportunity to gain experience in a wide variety of STEM disciplines. This paper describes work in progress on one such project, “MagnITO-Sat,” which consists of two picosatellites connected by a conductive tether. The ultimate aim of the tether is to provide electrodynamic thrust generation and power generation. This project will test three major components of the system: 1) the tether deployment mechanism; 2) the high- voltage biasing to enable current flow through a “phantom loop” formed by the conductive tether and the ionosphere; and 3) an optical (near-infrared) link that provides communication between the two picosatellites. A Globalstar radio transmits data and measurements to the ground. 1.0 Introduction Taylor University’s Senior Engineering Project engages engineering students in learning and applying systems design techniques to real-world projects. Previous projects include the design of three different satellites, one of which flew in Low Earth Orbit in 2014. -

1 Section 1.0 Tether Flights

SECTION 1.0 TETHER FLIGHTS 1 1.1 The Tethered Satellite System Program: TSS-1 and TSS-1R Missions Figure 1.1 TSS-1 Satellite and Tether Attached to 12 Meter Extendible Boom The Tethered Satellite System (TSS) was proposed to NASA and the Italian Space Agency (ASI) in the early 1970's by Mario Grossi, of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, and Giuseppe Colombo, of Padua University. A science committee, the Facilities Requirements Definition Team (FRDT), met in 1979 to consider the possible scientific applications for long tethers in space and whether the development of a tethered system was justified. The FRDT report, published in 1980, strongly endorsed a Shuttle-based tether system. A NASA-ASI memorandum of understanding was signed in 1984, in which NASA agreed to develop a deployer system and tether and ASI agreed to develop a special satellite for deployment. A science advisory team provided guidance on science accommodation requirements prior to the formal joint NASA-ASI Announcement of Opportunity for science investigations being issued in April, 1984. The purpose of the TSS was to provide the capability of deploying a satellite on a long, gravity-gradient stabilized tether from the Space Shuttle where it would provide a research facility for investigations in space physics and plasma-electrodynamics. Nine investigations were selected for definition for the first mission (TSS-1) in July, 1985. In addition, ASI agreed to provide CORE equipment (common to most investigations) that consisted of two electron guns, current and voltage monitors and a pressure gauge mounted on the Orbiter, and a linear accelerometer and an ammeter on the satellite.