Sara Mearns Soars in New York City Ballet's Bumpy Swan Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

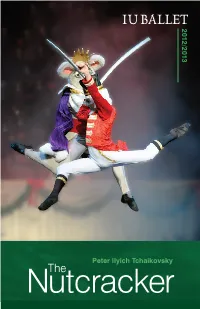

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

October 2020 New York City Center

NEW YORK CITY CENTER OCTOBER 2020 NEW YORK CITY CENTER SUPPORT CITY CENTER AND Page 9 DOUBLE YOUR IMPACT! OCTOBER 2020 3 Program Thanks to City Center Board Co-Chair Richard Witten and 9 City Center Turns the Lights Back On for the his wife and Board member Lisa, every contribution you 2020 Fall for Dance Festival by Reanne Rodrigues make to City Center from now until November 1 will be 30 Upcoming Events matched up to $100,000. Be a part of City Center’s historic moment as we turn the lights back on to bring you the first digitalFall for Dance Festival. Please consider making a donation today to help us expand opportunities for artists and get them back on stage where they belong. $200,000 hangs in the balance—give today to double your impact and ensure that City Center can continue to serve our artists and our beloved community for years to come. Page 9 Page 9 Page 30 donate now: text: become a member: Cover: Ballet Hispánico’s Shelby Colona; photo by Rachel Neville Photography NYCityCenter.org/ FallForDance NYCityCenter.org/ JOIN US ONLINE Donate to 443-21 Membership @NYCITYCENTER Ballet Hispánico performs 18+1 Excerpts; photo by Christopher Duggan Photography #FallForDance @NYCITYCENTER 2 ARLENE SHULER PRESIDENT & CEO NEW YORK STANFORD MAKISHI VP, PROGRAMMING CITY CENTER 2020 Wednesday, October 21, 2020 PROGRAM 1 BALLET HISPÁNICO Eduardo Vilaro, Artistic Director & CEO Ashley Bouder, Tiler Peck, and Brittany Pollack Ballet Hispánico 18+1 Excerpts Calvin Royal III New York Premiere Dormeshia Jamar Roberts Choreography by GUSTAVO RAMÍREZ -

WHERE the BOYS ARE SAB’S Boys Program Celebrates Tenth Anniversary

School of American Ballet Newsletter/Fall 2002 WHERE THE BOYS ARE SAB’s Boys Program Celebrates Tenth Anniversary ate afternoon visitors to SAB usually find the hall- vivid memories of his early years at SAB, dutifully com- ways teeming with young girls and boys, a colorful ing to class every afternoon to hang out with . girls. "At Lscene that more often than not leads newcomers to that age, you want camaraderie. I missed it. The boys spontaneously exclaim, "There are so many boys!" The today are psyched to come here to be with their pals. And sight of young boys pursuing ballet in large numbers it's much more inspiring for them when their classes can may still be unexpected to some, but at SAB it has become include learning how to do multiple pirouettes and dou- the norm—the result of a decade-long effort to increase ble tours. That's what they see Damian Woetzel and the School’s male enrollment and ultimately to bolster the Ethan Stiefel doing. That's what's going to inspire them to number of young men pursuing professional ballet continue with ballet. The co-ed children's classes when I careers. was a kid were much more focused on the girls—on barre work and preparing to dance en pointe." Just over 10 years ago, an internal review of SAB's pro- grams pointed up what Chairman of Faculty Peter As the Boys Program enters its eleventh year, it has tallied Martins believed was a major weakness: a longstanding 216 participants, including 57 who are still working their dearth of male students in the Children's Division. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Atheneum Nantucket Dance Festival

NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTIVAL 2011 Featuring stars of New York City Ballet & Paris Opera Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Dorothée Gilbert Teresa Reichlen Amar Ramasar Sterling Hyltin Tyler Angle Daniel Ulbricht Maria Kowroski Alessio Carbone Ana Sofia Scheller Sean Suozzi Chase Finlay Georgina Pazcoguin Ashley Laracey Justin Peck Troy Schumacher Musicians Cenovia Cummins Katy Luo Gillian Gallagher Naho Tsutsui Parrini Maria Bella Jeffers Brooke Quiggins Saulnier Cover: Photo of Benjamin Millepied by Paul Kolnik 1 Welcometo the Nantucket Atheneum Dance Festival! For 177 years the Nantucket Atheneum has enriched our island community through top quality library services and programs. This year the library served more than 200,000 adults, teens and children year round with free access to over 1.4 million books, CDs, and DVDs, reference and information services and a wide range of cultural and educational programs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition of educational and cultural programming, the Nantucket Atheneum is very excited to present a multifaceted dance experience on Nantucket for the fourth straight summer. This year’s performances feature the world’s best dancers from New York City Ballet and Paris Opera Ballet under the brilliant artistic direction of Benjamin Millepied. In addition to live music for two of the pieces in the program, this year’s program includes an exciting world premier by Justin Peck of the New York City Ballet. The festival this week has offered a sparkling array of free community events including two dance-related book author/illustrator talks, Frederick Wiseman’s film La Danse, Children’s Workshop, Lecture Demonstration and two youth master dance classes. -

World of Dancemagazine an UNCOMMON SIGHT Boca Ballet

Gateway to Florida Dance Community! Florida’s f March/April 2016 Magazine World o Dance AN UNCOMMON SIGHT The Next Generation of Male Dancers Boca Ballet Theatre’s 25th Anniversary Gala Performance How Dance Studios are Making the Most of their Space The Powerful Healthy Root: TURMERIC See our Featured Students WIN IT! NOW Win tickets to various performances around Florida. FREE PUBLICATION Supporting, Promoting and Preserving the Art of Dance! World of Dance Magazine FEATURES 20 12 14 25 26 CONTENTS 6 Break a Leg 21 Summer Special Editor’s Note 2016 Summer Intensive listings 7 Dance Highlights Dance Inspiration 25 Prevention Back Pain 8 Dance Highlights What’s going on ... 26 Healthy Eating & Lifestyle The Powerful Healthy Root: Turmeric 12 Students Insights Keeping your ankles in action 28 Featured Students Abigail Rodgers, Darriel Johnakin, 14 Studio Owners Kristen Gaertner, Emma Bell Pulling Double Duty 31 Win your tickets now! 17 Tribute Boca Ballet Theatre’s 25th Anniversary 32 Calendar of Events 18 Cover Spotlight Paris Ballet & Dance 38 Directory March/April 2016 .www.dancemagazineflorida.com .World of Dance Magazine 3 WEBSITE www.DanceMagazineFlorida.com Publisher/Editor/Feature Writer Karina Felix [email protected] The goal of WoDM is: To promote the achievements of Florida’s Dance Communities. To Support, Promote and Preserve Dance Developments. SUPPORTING: To highlight the efforts of Studio Owners, Teachers, Dancers, Students, Choreographers, Performing Art Schools, Theatres and all in the dance-related world PROMOTING: To share all dance events, performances, auditions, festivals, educational material, health issues, and art appreciation through this publication, weekly newsletters, Calendar of Events, Mark Your Calendar, Facebook, Twitter and Blogs; exposing and creating public appreciation & support. -

Duncan Stewart, CSA and Benton Whitley, CSA, Casting Directors

Duncan Stewart, CSA and Benton Whitley, CSA, Casting Directors/Partners Paul Hardt, Christine McKenna-Tirella, CSA Casting Director Ian Subsara, Emily Ludwig Casting Assistant Resume as of 3.15.2019 _________________________________________________________________ CURRENT & ONGOING: HADESTOWN Theater, Broadway – Walter Kerr Theater March 2019 – Open Ended Mara Isaacs, Hunter Arnold, Dale Franzen (Prod.) Rachel Chavkin (Dir.), David Newmann (Choreo.) By: Anais Mitchell CHICAGO THE MUSICAL Theater, Broadway – Ambassador Theater May 2008 – Open Ended Barry and Fran Weissler (Prod.) Walter Bobbie (Dir.), Ann Reinking (Choreo.) By: John Kander & Fred Ebb CHICAGO THE MUSICAL Theater, West End – Phoenix Theater March 2018 – Open Ended Barry and Fran Weissler (Prod.) Walter Bobbie (Dir.), Ann Reinking (Choreo.) By: John Kander & Fred Ebb ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST NBC Lionsgate TV Pilot March 2019 Richard Shepard (Dir.), Austin Winsberg (Writer) NY Casting AUGUST RUSH Theater, Regional – Paramount Theater January 2019 – June 2019 Paramount Theater (Prod.) John Doyle (Dir.), JoAnn Hunter (Choreo.) By: Mark Mancina, Glen Berger, David Metzger PARADISE SQUARE: An American Musical Theater, Regional – Berkeley Repertory Theatre December 2018 – March 2019 Garth Drabinsky (Prod.) ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Stewart/Whitley 213 West 35th Street Suite 804 New York, NY 10001 212.635.2153 Moisés Kaufman (Dir.), Bill T. Jones (Choreo.) By: Marcus Gardley, Jason Howland, Larry Kirwan, Craig Lucas, Nathan -

One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures / NEW BODIES

60 One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures / NEW BODIES ONE OF SIXTY-FIVE THOUSAND GESTURES / NEW BODIES Emmett Robinson Theatre at June 7, 7:30pm; June 8, 7:00pm; College of Charleston June 9, 2:00pm and 7:00pm; June 10, 2:00pm One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures (2012) Choreography Trisha Brown and Jodi Melnick Music Hahn Rowe Costume Design Yeohlee Teng Lighting Design Joe Levasseur Dancer Jodi Melnick For Burt and Trisha NEW BODIES (2016) Choreography Jodi Melnick Music Continuum by György Ligeti Retro-decay by Robert Boston (Original Track created for NEW BODIES) Passacaglia by Henrich Biber Violin Monica Davis Harpsichord Robert Boston Costume Design Marc Happel Lighting Design Joe Levasseur Moderator Nicole Taney Dancers Jared Angle, Sara Mearns, Taylor Stanley 1 hour | Performed without an intermission The 2018 dance series is sponsored by BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina. Additional support is provided by the Henry and Sylvia Yaschik Foundation. These performances are made possible in part through funds from the Spoleto Festival USA Endowment, generously supported by BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America. Produced by Works & Process at the Guggenheim. One of Sixty-Five Thousand Gestures / NEW BODIES 61 YEOHLEE TENG (costume designer) is the founder of Choreography YEOHLEE Inc., a fashion enterprise based in New York. Teng believes design serves a function. She believes that “clothes JODI MELNICK (dancer/choreographer) is honored with have magic. Their geometry forms shapes that can lend a a -

New York City Ballet Principal Dancer Sara Mearns to Perform Isadora Duncan Works in the 2018 Paul Taylor American Modern Dance New York Season at Lincoln Center

Contact: Lisa Labrado 646.214.5812 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEW YORK CITY BALLET PRINCIPAL DANCER SARA MEARNS TO PERFORM ISADORA DUNCAN WORKS IN THE 2018 PAUL TAYLOR AMERICAN MODERN DANCE NEW YORK SEASON AT LINCOLN CENTER NEW YORK, August 23, 2017 – Paul Taylor has invited New York City Ballet Principal Dancer Sara Mearns to perform works by Isadora Duncan reconstructed by The Isadora Duncan Dance Company Artistic Director, Lori Bellilove during the 2018 Season of Paul Taylor American Modern Dance (PTAMD) at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center. “We are thrilled to have Sara Mearns, a consummate artist with extraordinary stage presence, dance works by Isadora Duncan during our Season,” said Mr. Taylor. “As a founder of American modern dance, Isadora Duncan championed artistic freedom and individual expression. Her legacy continues to inspire each successive generation of American dancers and choreographers.” Ms. Mearns, who is well known for her interest in taking on new artistic challenges, said of the project, “I am so honored to be bringing Isadora Duncan’s dances to life and I’m inspired by the immense freedom that her dances offer me as an artist. Sharing this work with the audiences at the Paul Taylor American Modern Dance season is absolutely thrilling and very exciting.” A revolutionary in her art and life, Isadora Duncan (1877-1927) established what would become known as modern dance as an art on an equal footing with poetry, music, the visual arts and ballet, creating a new vision of dance as a means to express the inner self. -

2004 Annual Report

2004 Annual Report Mission Statement Remembering Balanchine Peter Martins - Ballet Master in Chief Meeting the Demands Barry S. Friedberg - Chairman New York City Ballet Artistic NYCB Orchestra Board of Directors Advisory Board Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration 2003-2004 The Centennial Celebration Commences & Bringing Balanchine Back-Return to Russia On to Copenhagen & Winter Season-Heritage A Warm Welcome in the Nation's Capital & Spring Season-Vision Exhibitions, Publications, Films, and Lectures New York City Ballet Archive New York Choreographic Institute Education and Outreach Reaching New Audiences through Expanded Internet Technology & Salute to Our Volunteers The Campaign for New York City Ballet Statements of Financial Position Statements of Activities Statements of Cash Flows Footnotes Independent Auditors' Report All photographs by © Paul Kolnik unless otherwise indicated. The photographs in this annual report depict choreography copyrighted by the choreographer. Use of this annual report does not convey the right to reproduce the choreography, sets or costumes depicted herein. Inquiries regarding the choreography of George Balanchine shall be made to: The George Balanchine Trust 20 Lincoln Center New York, NY 10023 Mission Statement George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein formed New York City Ballet with the goal of producing and performing a new ballet repertory that would reimagine the principles of classical dance. Under the leadership of Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins, the Company remains dedicated to their vision as it pursues two primary objectives: 1. to preserve the ballets, dance aesthetic, and standards of excellence created and established by its founders; and 2. to develop new work that draws on the creative talents of contemporary choreographers and composers, and speaks to the time in which it is made. -

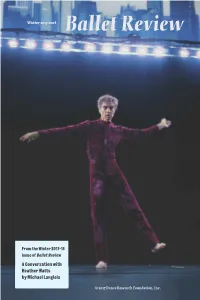

Michael Langlois

Winter 2 017-2018 B allet Review From the Winter 2017-1 8 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Heather Watts by Michael Langlois © 2017 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. 4 New York – Elizabeth McPherson 6 Washington, D.C. – Jay Rogoff 7 Miami – Michael Langlois 8 Toronto – Gary Smith 9 New York – Karen Greenspan 11 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 12 New York – Susanna Sloat 13 San Francisco – Rachel Howard 15 Hong Kong – Kevin Ng 17 New York – Karen Greenspan 19 Havana – Susanna Sloat 46 20 Paris – Vincent Le Baron 22 Jacob’s Pillow – Jay Rogoff 24 Letter to the Editor Ballet Review 45.4 Winter 2017-2018 Lauren Grant 25 Mark Morris: Student Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino and Teacher Managing Editor: Joel Lobenthal Roberta Hellman 28 Baranovsky’s Opus Senior Editor: Don Daniels 41 Karen Greenspan Associate Editors: 34 Two English Operas Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan Claudia Roth Pierpont Alice Helpern 39 Agon at Sixty Webmaster: Joseph Houseal David S. Weiss 41 Hong Kong Identity Crisis Copy Editor: Naomi Mindlin Michael Langlois Photographers: 46 A Conversation with Tom Brazil 25 Heather Watts Costas Associates: Joseph Houseal Peter Anastos 58 Merce Cunningham: Robert Gres kovic Common Time George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall Daniel Jacobson Paul Parish 70 At New York City Ballet Nancy Reynolds James Sutton Francis Mason David Vaughan Edward Willinger 22 86 Jane Dudley on Graham Sarah C. Woodcock 89 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photograph by Tom Brazil: Merce Cunningham in Grand Central Dances, Dancing in the Streets, Grand Central Terminal, NYC, October 9-10, 1987.