Creating a Commemorative Site on the Heritage and Memory of Cotton Pickers in the Mississippi Delta: a Community Driven Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invention of a Slave

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Winter 2018 Invention of a Slave Brian L. Frye University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Frye, Brian L., "Invention of a Slave" (2018). Law Faculty Scholarly Articles. 619. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/619 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Invention of a Slave Notes/Citation Information Brian L. Frye, Invention of a Slave, 68 Syracuse L. Rev. 181 (2018). This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/619 INVENTION OF A SLAVE Brian L. Fryet CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ ..... 1 81 I. ANTEBELLUM REQUIREMENTS FOR PATENTABILITY ........... 183 II. ANTEBELLUM AFRICAN-AMERICAN PATENTS ....... ...... 185 III. INVENTION OF A SLAVE ............................... 1 87 A. Ned's "Double Plow and Scraper....... ....... 189 B. Benjamin T. Montgomery's "Canoe-Paddling" Propeller. ................................ 210 1. Benjamin T. Montgomery ............. ..... 210 2. Jefferson Davis's Attempt to PatentMontgomery's Propeller ......................... .... 212 3. Davis Bend During the Civil War...... ...... 213 4. Montgomery's Attempt to PatentHis Propeller... 214 5. Davis Bend After the Civil War .... -

KNOWLES-DOCUMENT-2014.Pdf

Abstract Fashioning Slavery: Slaves and Clothing in the U.S. South, 1830–1865 By Katie Knowles This dissertation examines such varied sources as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Eastman Johnson’s genre paintings, runaway advertisements, published narratives, plantation records, the WPA ex-slave narratives, and nearly thirty items of clothing with provenance connections to enslaved wearers. The research presented in the following pages seeks to reveal the complexities surrounding clothing and slave life in the antebellum South by examining a variety of sources in combination. Enslaved people resisted race-based slavery by individualizing their appearance when working and when playing, but they were ultimately unsuccessful in resisting their exclusion from the race-based American fashion system. In bringing together previous scholarship on slavery in the American South, material culture, and fashion studies, this project reveals the deep connections between race and fashion in the antebellum United States. Enslaved people struggled against a racist culture that attempted to exclude them as valid participants in American culture. The individuality expressed by slaves through personalizing their clothing was a tactic of resistance against racism and race- based slavery. In many instances, enslaved people chose to acquire and dress in fashionable Euro-American clothing, a method of resistance because it was an attempt by them to disrupt the racially exclusionary fashion system of the antebellum United States. Though relatively few garments survive today, the voices of enslaved people and the records of their oppressors provide a rich narrative that helps deconstruct the many ways in which slaves encountered clothing. Clothing played an integral part in the daily life of enslaved African Americans in the antebellum South and functioned in multi-faceted ways across the antebellum United States to racialize and engender difference, and to oppress a variety of people through the visual signs and cues of the fashion system. -

Isaiah T. Montgomery and the Mississippi Constitution: STRATEGY UNDER EXTREME ADVERSITY (Revised to December 12 2016 ) (Copyright, 2016

Isaiah T. Montgomery and the Mississippi Constitution: STRATEGY UNDER EXTREME ADVERSITY (Revised to December 12 2016 ) (Copyright, 2016. Matthew Holden Jr. EDIT FOR GLITCHES Isaiah T. Montgomery and the Mississippi Constitution: Strategy under Extreme Adversity Matthew Holden, Jr. President, Isaiah T. Montgomery Studies Project. [email protected]( .) Retired Wepner Distinguished Professor in Political Science, University of Illinois at Springfield; Professor Emeritus of Politics, University of Virginia. Introduction This paper is an outgrowth from the notes used in a roundtable on March 19, 2016. The roundtable was proposed to the National Conference of Black Political Scientists (NCOBPS), and approved for its 2016 meeting in Jackson, Mississippi. The roundtable was held in the House of Representatives Chamber in the Old Capitol Museum, and was 1 open without charge to any member of the public. 1. Todd C. Shaw, 2016 President of National Conference of Black Politica Scientist s (NCOBPS), and Sekou Franklin, 2016 Program Co-Chair, encouraged and assisted in the scheduling of the roundtable. Katherine Blount (Director, Mississippi Department of Archives and History), Connie Michael (Facilities Use Coordinator, The Old Capitol Museum, and Trey Roberts (Mississippi Department of Archives and History) assisted in getting the use of the chamber and in presenting information on the Mississippi 2Museums project. The cost of the chamber was paid by Matthew Holden, Jr, from private income in behalf of the Isaiah T. Montgomery Studies Project. The chair of the round table was Michael V. Williams, Dean of the Social Science Division Tougaloo College. The other participants were Dorothy Pratt (University of South Carolina).Jeanne Middleton-Hairston (Millsaps College), Byron D’Andra Orey (Jackson State University), and Dr. -

American Legacy; My African American Heroes; 1998 Andre Braugher

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Magazines, Books & Papers: African American Buffalo Quarters Historical Society Papers | Experience Batchelor, Lillion 1998 American Legacy; My African American Heroes; 1998 Andre Braugher A. Philip Randolph Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/magazines-books Recommended Citation "American Legacy; My African American Heroes; 1998." Batchelor, Lillion | Buffalo Quarters Historical Society Papers. Digital Collections. Monroe Fordham Regional History Center, Archives & Special Collections Department, E. H. Butler Library, SUNY Buffalo tS ate. http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/magazines-books/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Buffalo Quarters Historical Society Papers | Batchelor, Lillion at Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Magazines, Books & Papers: African American Experience by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Buffalo tS ate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. As OUR PUBLISHER, R ODNEY R EYNOLDS, EX and other NAACP activists to begin the na Some well-known plained in the letter that opens this issue, he tional campaign to register black voters in recently sent a query to leaders in politics, the heart of the racially segregated South. He the arts, and education, asking them to name was not seeking fame or notoriety; he did not Americans tell their African-American hero in history-the go to be a leader. He traveled to Mississippi person whose accomplishments they most to help others learn to lead. us of theAJrican admire. We received a heartening number of I met Bob Moses about twenty-fi ve years responses that offered a variety of candidates later while doing research for the documentary A mericans they as well as a few repeats. -

Art and the Cotton Trade in the Indian and Atlantic Ocean Worlds, 1770

Threads of Empire: Art and the Cotton Trade in the Indian and Atlantic Ocean Worlds, 1770-1930 Anna Arabindan-Kesson PhD Prospectus, History of Art and African American Studies, Yale University, 2010 “if you take a handkerchief and spread it out … you can see in it certain fixed distances. Then take the 1 same handkerchief and crumple it … Two distant points are suddenly very close, even superimposed” Cotton fabric inscribed a new economic geography on the contours of the Indian and Atlantic oceanic spaces, through its cultivation and by the routes of trade that connected ports, cities and plantations. Drawing on material culture studies, histories of slavery and art histories of empire this dissertation identifies cotton as a paradigmatic material of empire.2 Cotton cloth wove together a colonial trade in commodities that was underpinned by the slave trade. The subject of my dissertation is cloth: its materiality, the historical and social process from its making to its consumption, and the theoretical paradigm of representation it opens up. The dissertation will show how the look and feel of cotton cloth was embedded in, and inflected by, the historical and commercial networks that shaped its production and use. Cloth’s ability to drape, shape and dress gives it a screen-like quality: inscribed upon, yet it can also inscribe. These are not 1 Michel Serres and Bruno Latour, Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time (University of Michigan Press, 1995), 60. 2 James Walvin, Fruits of Empire : Exotic Produce and British Taste, 1660-1800 (New York :: New York University Press, 1997). 1 simply metaphors for the process of representation. -

The Elaine Riot of 1919: Race, Class, and Labor in the Arkansas Delta

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2019 The Elaine Riot of 1919: Race, Class, and Labor in the Arkansas Delta Steven Anthony University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Anthony, Steven, "The Elaine Riot of 1919: Race, Class, and Labor in the Arkansas Delta" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 2154. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2154 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ELAINE RIOT OF 1919: RACE, CLASS, AND LABOR IN THE ARKANSAS DELTA by Steven Anthony A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2019 ABSTRACT THE ELAINE RIOT OF 1919: RACE, CLASS, AND LABOR IN THE ARKANSAS DELTA by Steven Anthony The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2019 Under the Supervision of Professor Gregory Carter This dissertation examines the racially motivated mob dominated violence that took place during the autumn of 1919 in rural Phillips County, Arkansas nearby Elaine. The efforts of white planters to supplant the loss of enslaved labor due to the abolition of American slavery played a crucial role in re-making the southern agrarian economy in the early twentieth century. My research explores how the conspicuous features of sharecropping, tenant farming, peonage, or other variations of debt servitude became a means for the re-enslavement of African Americans in the Arkansas Delta. -

Why Did He Do This?

Program: “Road Map to Racism” – Making of 1890 Mississippi Constitution Speaker: Dorothy O. Pratt, Professor of History Emeritus, University of Notre Dame Guests: Linda Yee, David Schimmelpfennig, Nancy Schimmelpfennig, Everett Schimmelpfennig, Lars Schimmelpfennig, Sisir and Heather Dhar Attendance: 104 Introduced and Sponsored By: Bob Yee Scribe: Bill Elliott Editor: Bill Elliott Today’s interesting talk was taken from the book “Sowing the Wind: The Mississippi Constitutional Convention of 1890” which was written after 9 years of research by today’s speaker, Dorothy Pratt. The talk was about one particular person involved in the 1890 constitutional convention for Mississippi which rewrote the constitution of Mississippi previously adopted after the civil war. The person in question was Isaiah Montgomery, a wealthy black man from Mississippi. He was the only black delegate to the 1895 constitutional convention. Black persons at that time railed against his involvement in the convention, calling him a Judas to his race. The talk today was to tell, as Paul Harvey said “The rest of the story”. In doing this, she partially rehabilitates Isaiah for his part in the convention. Included in the convention were Senator J.Z. George, who crafted the new constitution as well as other white legislators, and Isaiah Montgomery. Excluded were 2 black senators Hiram Rubbles, and Blanche Bruce and John Roy Lynch, member of the U. S. House or Representatives. The purpose of the convention was to have the power remain in the hands of the paternalistic white population who were only 45% of the population, and suppress the vote of the 55% black majority. -

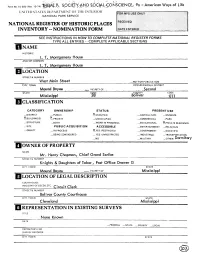

Isaiah T. Montgomery House Was Constructed

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ilf : 9; >SpCJEjrY :AND SOCIALCONSCIENCE, 9a - American Ways of Life UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS iNAME HISTORIC 1. T. Montgomery House AND/OR COMMON I. T. Montgomery House [LOCATION STREET& NUMBER West Main Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN . CQNGRESSIQNAL DISTRICT Mound $ayou ,^_*_ VANITY, OF , ( . , Second STATE . CODE CQyNTY CODE Mississippi 28 Bolivar Oil CLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE —DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^.BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE __BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER Dormitory OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. Henry Chapman, Chief Grand Scribe STREET & NUMBER Knights & Daughters of Tabor, Post Office Drawer G CITY, TOWN STATE Mound Bayou _ VICINITY OF Mississippi HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REdSTRYOFDEEDS.ETC. C J^f C | erk STREET& NUMBER Bolivar County Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Cleveland Mississippi H REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None Known DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE __GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE————— X_FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house is a 1910 red brick structure of two stories over a full above-grade basement, irregular in plan, with hipped roof and gables over projections. -

Town and Country in the Old South : Vicksburg and Warren County, Mississippi, 1770-1860

TOWN AND COUNTRY IN THE OLD SOUTH: VICKSBURG AND WARREN COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI, 1770-1860 By CHRISTOPHER CHARLES MORRIS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1991 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am pleased to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement of a number of people, and to thank them for their kindness. Sam Hill and Helen Hill gave me a place to stay when I made my first visit to Jackson. At Vicksburg the staff at the Old Court House Museum received me with open arms. Gordon Cotton's and Blanche Terry's knowledge of Warren County history and of the local documents proved invaluable. The staff at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History was always helpful. In particular I want to thank Anne Lipscombe. Alison Beck, of the Barker Texas History Center at the University of Texas, helped me wade through much of the as yet largely uncatalogued Natchez Trace Collection. She brought several important documents to my attention that I never could have found on my own. Several people in Vicksburg and Warren County took an interest in my work and helped me to discover their past. Special thanks go to Dee and John Leigh Hyland for being so forthcoming with their family history. Two other local researchers gave me the benefit of their experience. Clinton Bagley guided me through the records in the Adams County Courthouse in Natchez, and Charles L. Sullivan helped me find my way through the massive Claiborne Collection in the ii Mississippi Department of Archives and history. -

The Life and Works of Winslow Homer

i^','i yv^ ijj.B.CLARK£ cn Qni'5;tLL£RS«ST»Tm..ri THE LIFE AND WORKS OF WINSLOW HOMER PORTIL^IT OF WINSLOW HOMER AT THE AGE OF SEVENTY-TWO From a photograph taken at Prout's Neck, Maine, in igo8. Photogravure 1 y^ff THE'T'ttt:^ LIFEt ti AND WORKS OF WINSLOW HOMER BY WILLIAM HOWE DOWNES WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY 191 JNJMAA/j«^G LIBRARY JUL 19™ i5[!15WW OCT 2 :M332 iNSTITUTlOW HATiOMAL COLL^^iiuji Of FINE AHW COPYRIGHT^ J911, BY WILLIAM HOWE DOWNES ALL RIGHTS RESER\'ED Published October iqii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS THE author is grateful to all those persons who have aided him in the preparation of this biography. To Winslow Homer's two brothers he owes especially cordial thanks. Mr. Charles S. Homer has been most kind in lending indispensable assistance and most patient in an- swering questions. Mr. Arthur B. Homer with fortitude has listened to the reading of the entire manuscript, and has given wise and valuable counsel and criticism. To Mr. Arthur P. Homer and Mr. Charles Lowell Homer of Boston the author is indebted for many useful suggestions and interesting remi- niscences. Mr. Joseph E. Baker, the friend and comrade of Winslow Homer in his youth, and his fellow-apprentice in BufTord's lithographic establishment in Boston, from 185510 1857, has supplied interesting data which could have been obtained from no other source. Mr. Walter Rowlands, of the fine arts department of the Boston Public Library, has made himself useful in the line of historic research, for which his experience admirably qualifies him, and has gone over the first rough draft of the manuscript and offered many friendly hints and suggestions for its betterment. -

News Release the Metropolitan Museum of Art

news release The Metropolitan Museum of Art For Release: Immediate Contact: Harold Holzer Jill Schoenbach LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENTS OF WINSLOW HOMER ON VIEW AT METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Major Retrospective Exhibition Will Include Works in All Media Exhibition dates: June 20 - September 22,1996 Exhibition location: European Paintings Galleries, second floor Press preview: Monday, June 17,10 a.m. - noon The creative power and versatility of one of America's greatest painters will be on view in the major retrospective exhibition Winslow Homer, opening June 20 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The most comprehensive presentation of Homer's art in more than 20 years, the exhibition will include approximately 180 paintings, drawings, and watercolors, and will offer a broad vision of his achievements over five decades. The exhibition, which was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, comes to New York after showings at the National Gallery and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where it has been a great critical and popular success. The exhibition is made possible by GTE Corporation. Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum, commented: "Homer's wide-ranging pictorial style and technical virtuosity have earned him a place among the nation's indisputable masters. This summer, we are proud to display the full range of Homer's genius to visitors to the Museum from across America and around the world." "GTE is honored to join The Metropolitan Museum of Art in presenting Winslow Homer. GTE's involvement in this exhibition is a corollary to our role in communications. Our support of the arts and education reflects our desire to enhance the quality of life in our society, challenge the human spirit, and enjoy the product of creative genius," said Charles R. -

Foundation Document Vicksburg National Military Park Mississippi October 2014 Foundation Document

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Vicksburg National Military Park Mississippi October 2014 Foundation Document To Snyder’s and BUS Haynes’ bluffs CHICKASAW BAYOU 61 BATTLEFIELD 61 Sh erm an A v e n u e Grant’s Headquarters U.S.S. Cairo Area Museum Information Vicksburg National Pennsylvania Cemetery New Hampshire Navy Massachusetts 7 VICKSBURG NATIONAL Sherman Rhode Island 8 Battery Circle New York Gran e Selfridge MILITARY PARK t nu Ave Y ion Ave Kansas AZ Un nue OO Thayer’s Approach 6 African American Monument e R u Stockade IV n Conf ad ER e ederate A Ro DIVE Av Tennessee v RS e Redan rd IO g n a N in u ey t v Stockade Redan c e G ra e 9 5 C n Attack A n Fort Hill o e 10 ) N C u en West Virginia A v A T L Arkansas Missouri Cedar Hill e Cemetery m v r N i a r F (Confederate y D k Wisconsin I section) S t ll e i oad e H Ransom’s R r son O t Jack St r 4 ) Gun Path ern o od F (m P n o Third t Louisiana ng Luther K i rtin ing B Ma Jr l Shirley h v Redan 2 d 61 as 3 House M W i s s Louisiana Pe Illinois i m o b e n r Great Redoubt 11 t 6 o n 1 Battery De Golyer 6 t Surrender e A re v M t ain S Interview e t Site as Michigan E e R Jackson o u a n Mississippi e d e 3 v u A n Old Court House e 6 Pemberton Circle v Museum e t A 8 To Big Black River Bridge, Gro a (open to public) ve St r Champion Hill, Raymond, 1 reet St e and Jackson battlefields d Minnesota C ra e wford f Pemberton’s Headquarters n n Second Texas (open on a limited basis) o o Cla i y C Stre Lunette n et Exit 5 12 U 20 Visitor y r er