Negotiating the Filipino in Cyberspace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

The Impact of 'Korean Wave'on Young Indonesian Females and Indonesian Culture in Jabodetabek Area

THE IMPACT OF ‘KOREAN WAVE’ ON YOUNG INDONESIAN. Putri And Reese THE IMPACT OF ‘KOREAN WAVE’ ON YOUNG INDONESIAN FEMALES AND INDONESIAN CULTURE IN JABODETABEK AREA Vandani Kencana Putri Matthias Reese Swiss German University, Tangerang, Indonesia Swiss German University, Tangerang, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Popular culture ‘Korean Wave’ has been reaching out all over the world since the year 2000 with the phenomenon intriguing people’s interests towards Korean culture and products. In fact, some Abstract people already prefer Korean culture and products to those from their own country. It is inevitable in Indonesia, too, where most of its K-Wave-enthusiasts are teenage to adult females. With this in mind, there is a possibility that Indonesian culture might eventually vanish in those individuals. Thus, this quantitative research focuses on Indonesian female K-Wavers between 15 and 30 years old who are living in the Jabodetabek area, and investigates their main medium of Korean Wave consumption and whether Korean Wave has an impact on individuals and on Indonesian culture itself. The results based on the data of 251 respondents show that internet is the main medium of Korean Wave consumption in the Jabodetabek area. Furthermore, the results injdicate that the Korean Wave does significantly impact Indonesian female K-Wavers in several aspects, but an impact of the Korean Wave on Indonesian culture could not be found. 35 BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES JOURNAL c MARC 2016 . VOL. 3 . NO.2 I. Background pop music (or K-Pop) also made a major contribution for the geographical orean popular culture, called extension of the Korean Wave across ‘Korean Wave’ or simply the globe. -

Las Vegas Channel Lineup

Las Vegas Channel Lineup PrismTM TV 222 Bloomberg Interactive Channels 5145 Tropicales 225 The Weather Channel 90 Interactive Dashboard 5146 Mexicana 2 City of Las Vegas Television 230 C-SPAN 92 Interactive Games 5147 Romances 3 NBC 231 C-SPAN2 4 Clark County Television 251 TLC Digital Music Channels PrismTM Complete 5 FOX 255 Travel Channel 5101 Hit List TM 6 FOX 5 Weather 24/7 265 National Geographic Channel 5102 Hip Hop & R&B Includes Prism TV Package channels, plus 7 Universal Sports 271 History 5103 Mix Tape 132 American Life 8 CBS 303 Disney Channel 5104 Dance/Electronica 149 G4 9 LATV 314 Nickelodeon 5105 Rap (uncensored) 153 Chiller 10 PBS 326 Cartoon Network 5106 Hip Hop Classics 157 TV One 11 V-Me 327 Boomerang 5107 Throwback Jamz 161 Sleuth 12 PBS Create 337 Sprout 5108 R&B Classics 173 GSN 13 ABC 361 Lifetime Television 5109 R&B Soul 188 BBC America 14 Mexicanal 362 Lifetime Movie Network 5110 Gospel 189 Current TV 15 Univision 364 Lifetime Real Women 5111 Reggae 195 ION 17 Telefutura 368 Oxygen 5112 Classic Rock 253 Animal Planet 18 QVC 420 QVC 5113 Retro Rock 257 Oprah Winfrey Network 19 Home Shopping Network 422 Home Shopping Network 5114 Rock 258 Science Channel 21 My Network TV 424 ShopNBC 5115 Metal (uncensored) 259 Military Channel 25 Vegas TV 428 Jewelry Television 5116 Alternative (uncensored) 260 ID 27 ESPN 451 HGTV 5117 Classic Alternative 272 Biography 28 ESPN2 453 Food Network 5118 Adult Alternative (uncensored) 274 History International 33 CW 503 MTV 5120 Soft Rock 305 Disney XD 39 Telemundo 519 VH1 5121 Pop Hits 315 Nick Too 109 TNT 526 CMT 5122 90s 316 Nicktoons 113 TBS 560 Trinity Broadcasting Network 5123 80s 320 Nick Jr. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Catharine J. Cadbury Papers HC.Coll.1192

William W. Cadbury and Catharine J. Cadbury papers HC.Coll.1192 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit February 23, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections 2011 370 Lancaster Ave Haverford, PA, 19041 610-896-1161 [email protected] William W. Cadbury and Catharine J. Cadbury papers HC.Coll.1192 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 William Warder Cadbury (1877-1959)......................................................................................................... 6 Catharine J. Cadbury (1884-1970)................................................................................................................ 6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Related Finding Aids.....................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory................................................................................................................................... -

Diaspora Philanthropy: the Philippine Experience

Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience ______________________________________________________________________ Victoria P. Garchitorena President The Ayala Foundation, Inc. May 2007 _________________________________________ Prepared for The Philanthropic Initiative, Inc. and The Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University Supported by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ____________________________________________ Diaspora Philanthropy: The Philippine Experience I . The Philippine Diaspora Major Waves of Migration The Philippines is a country with a long and vibrant history of emigration. In 2006 the country celebrated the centennial of the first surge of Filipinos to the United States in the very early 20th Century. Since then, there have been three somewhat distinct waves of migration. The first wave began when sugar workers from the Ilocos Region in Northern Philippines went to work for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association in 1906 and continued through 1929. Even today, an overwhelming majority of the Filipinos in Hawaii are from the Ilocos Region. After a union strike in 1924, many Filipinos were banned in Hawaii and migrant labor shifted to the U.S. mainland (Vera Cruz 1994). Thousands of Filipino farm workers sailed to California and other states. Between 1906 and 1930 there were 120,000 Filipinos working in the United States. The Filipinos were at a great advantage because, as residents of an American colony, they were regarded as U.S. nationals. However, with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which officially proclaimed Philippine independence from U.S. rule, all Filipinos in the United States were reclassified as aliens. The Great Depression of 1929 slowed Filipino migration to the United States, and Filipinos sought jobs in other parts of the world. -

Star Channels, Feb. 18-24

FEBRUARY 18 - 24, 2018 staradvertiser.com REAL FAKE NEWS English comedian John Oliver is ready to take on politicians, corporations and much more when he returns with a new season of the acclaimed Last Week Tonight With John Oliver. Now in its fi fth season, the satirical news series combines comedy, commentary and interviews with newsmakers as it presents a unique take on national and international stories. Premiering Sunday, Feb. 18, on HBO. – HART Board meeting, live on ¶Olelo PaZmlg^qm_hkAhghenenlkZbemkZglbm8PZm\aebo^Zg]Ûg]hnm' THIS THURSDAY, 8:00AM | CHANNEL 55 olelo.org ON THE COVER | LAST WEEK TONIGHT WITH JOHN OLIVER Satire at its best ‘Last Week Tonight With John hard work. We’re incredibly proud of all of you, In its short life, “Last Week Tonight With and rather than tell you that to your face, we’d John Oliver” has had a marked influence on Oliver’ returns to HBO like to do it in the cold, dispassionate form of a politics and business, even as far back as press release.” its first season. A 2014 segment on net By Kyla Brewer For his part, Bloys had nothing but praise neutrality is widely credited with prompt- TV Media for the performer, saying: “His extraordinary ing more than 45,000 comments on the genius for rich and intelligent commentary is Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) s 24-hour news channels, websites and second to none.” electronic filing page, and another 300,000 apps rise in popularity, the public is be- Oliver has worked his way up through the comments in an email inbox dedicated to Acoming more invested in national and in- entertainment industry since starting out as a proposal that would allow “priority lanes” ternational news. -

2014 Estados Unidos ? Oportunidades Para Alimentos Bebidas E Agronegócios Brasileiros

ESTADOS UNIDOS PERFIL E OPORTUNIDADES COMERCIAIS PARA ALIMENTOS, BEBIDAS E AGRONEGÓCIOS 2014 1 Apex-Brasil Mauricio Borges PRESIDENTE Ricardo Santana DIRETOR DE NEGÓCIOS Tatiana Porto DIRETORA DE GESTÃO CORPORATIVA Marcos Tadeu Caputi Lélis GERENTE EXECUTIVO DE ESTRATÉGIA CORPORATIVA E NEGÓCIOS AUTORES DO ESTUDO: Leonardo Silva Machado Rafaela Alves Albuquerque GERÊNCIA DE INTELIGÊNCIA COMERCIAL E COMPETITIVA – APEX-BRASIL Mary Ann Ribeiro Blackburn SECOM DO CONSULADO DO BRASIL EM HOUSTON, TX Agradecimento especial à Embaixada do Brasil em Washington, aos SECOMs dos Consulados do Brasil em New York, Chicago e Houston pelo apoio logístico e informacional que possibilitou o sucesso da Missão Prospectiva de Inteligência Comercial nos Estados Unidos. E também aos colegas dos Escritórios da Apex- Brasil em São Francisco e em Miami, em especial ao Sr. Fernando Spohr que participou ativamente das reuniões durante a missão. Todos contribuíram com informações que enriqueceram este estudo. SEDE Setor Bancário Norte, Quadra 02, Lote 11, CEP 70.040-020 Brasília – DF Tel.: 55 (61) 3426-0202 Fax: 55 (61) 3426-0263 www.apexbrasil.com.br E-mail: [email protected] © 2014 Apex-Brasil Qualquer parte desta obra poderá ser reproduzida, desde que citada a fonte. 2 APRESENTAÇÃO Este estudo tem o intuito de fornecer informações às empresas brasileiras que pretendam acessar o mercado dos Estados Unidos. Além de apresentar um panorama socioeconômico, comercial e loGístico do país, o estudo destaca as principais oportunidades de exportação para as empresas brasileiras do complexo alimentos, bebidas e aGroneGócios que queiram atuar no mercado norte-americano. ÍNDICE PÁGINA SUMÁRIO EXECUTIVO PaG. 4 ASPECTOS GEOGRÁFICOS E SOCI OEC ONÔ MICOS PaG. -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

Appendix .Pdf

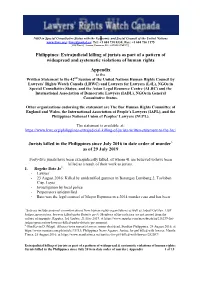

NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations www.lrwc.org; [email protected]; Tel: +1 604 738 0338; Fax: +1 604 736 1175 3220 West 13th Avenue, Vancouver, B.C. CANADA V6K 2V5 Philippines: Extrajudicial killing of jurists as part of a pattern of widespread and systematic violations of human rights Appendix to the Written Statement to the 42nd Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council by Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada (LRWC) and Lawyers for Lawyers (L4L), NGOs in Special Consultative Status; and the Asian Legal Resource Centre (ALRC) and the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL), NGOs in General Consultative Status. Other organizations endorsing the statement are The Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales, the International Association of People’s Lawyers (IAPL), and the Philippines National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL). The statement is available at: https://www.lrwc.org/philippines-extrajudicial-killing-of-jurists-written-statement-to-the-hrc/ __________________________________________________________________________ Jurists killed in the Philippines since July 2016 in date order of murder1 as of 29 July 2019 Forty-five jurists have been extrajudicially killed, of whom 41 are believed to have been killed as a result of their work as jurists. 1. Rogelio Bato Jr2 - Lawyer - 23 August 2016: Killed by unidentified gunmen in Barangay Lumbang 2, Tacloban City, Leyte - Investigation by local police - Perpetrators unidentified - Bato was the legal counsel of Mayor Espinosa in a 2014 murder case and has been 1 Sources include personal communications from human rights organizations as well as Jodesz Gavilan. -

Optik TV Channel Listing Guide 2020

Optik TV ® Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver/ Kelowna/ Prince Dawson Victoria/ Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 Alberta Assembly TV ABLEG 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 100 100 100 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 Citytv Calgary* CKALDT ● ● ● ● ● 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● — Citytv Vancouver* -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman