Master 2-2006.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just Aircraft Superstol a Helio for the Light-Sport Set

The Spirit of Homebuilt Aviation I www.eaa.org Vol.2 No.8 I August 2013 Just Aircraft SuperSTOL A Helio for the light-sport set When the Kit Doesn’t Arrive E-LSA—Make It Your Way The ULPower Six-Cylinder Engine More About Sawtooth Climbs Tower Frequency It’s Time to Celebrate By Jack Pelton It’s time for Oshkosh, the best week of the year. And, as instead of shrinking. People are so dedicated to preserving always, we have many reasons to celebrate our love of all fl ying history that restoration projects once thought to be things that fl y. impossible are now almost routine. During the rest of the year it’s easy for me, and I’m sure Even the standard category airplanes nearly all look their you, too, to become bogged down by the steady drumbeat best. No airplane owner wants to fl y to Oshkosh without of bad news and threats to personal aviation from all cor- fi rst washing and polishing his airplane and making it look ners. And at EAA we are always on guard to protect our as good as it possibly can. All pilots who fl y to Oshkosh freedom to fl y and to keep personal aviation accessible take immense pride in their airplane and their accomplish- to as many people as possible. But at Oshkosh, during ments as pilots no matter what they fl y. AirVenture, is the time to recognize just how successful we have been. In 1975 Tom Poberezny was named chairman of the Oshkosh fl y-in. -

Kiwiflyer ZK-REVIEW IS PROVIDED COURTESY OF

KiwiFlyer ZK-REVIEW IS PROVIDED COURTESY OF Contributed by Penny Belworthy ARRIVALS - April/May 2010 ZK-MWS ZK-VDB Sonex CDT P & M Aviation Pegasus Quantum Mr R D Mason Rangiora Microlight Class 2 DDB Avid Mark IV Microlight Mr A J McNeal Whangarei Microlight Class 2 ZK-CDT P&M Aviation Mike Whittaker MW6S HIJ Robinson R22 Beta CHL Investments Ltd Christchurch Helicopter HJU Schweizer 269C-1 The Reliance Group Limited Papakura Helicopter Pegasus Quantum Trike THE Mike Whittaker MW6S aircraft was HQK Eurocopter AS 350 B3 Faram Aviation Group Limited Hastings Helicopter HSE Aerospatiale AS 350B Rotor Flite N.Z. Limited Clevedon Helicopter DIAMOND DA20 designed in the UK and since 1986 there HUM Robinson R44 II Heliflite Pacific Limited Papakura Helicopter HXB Robinson R44 II Partner Group Limited Auckland Helicopter have been 42 registered. Having built boats, IHF Eurocopter AS 355 F2 Helicopter Services (BOP) Ltd Taupo Helicopter cars and houses, Grant Sandiford felt it was KAW Pacific Aerospace 750XL Pacific Aerospace Limited Hamilton Aeroplane KBA Pacific Aerospace 750XL Pacific Aerospace Limited Hamilton Aeroplane time to build a plane from plans and began KFB Gulfstream GV-SP ExecuJet New Zealand Limited Wellington Aeroplane this project about 5 years ago. MAR Cessna 182T Mr R B C Shepherd Rotorua Aeroplane MWS Mike Whittaker MW6S Mr G Sandiford North Shore City Microlight Class 2 The MW6S has an aluminum structure, RIG Acorn Industries UFO Heli-Thruster Mr G W Price Whitford Gyroplane SPR TL TL-3000 Sirius Sport Aircraft Ltd North Shore City Microlight Class 2 plywood wing ribs which are fibreglassed SUS TL TL-3000 Sirius Sport Aircraft Ltd North Shore City Microlight Class 2 to the spar and then the whole structure is FOR Mark Norgate of Whangarei the SWG Piper PA-28-181 Southern Wings Limited Invercargill Aeroplane TLS Tecnam P92 Echo Classic de luxe Ardmore Aviation & Giovanni Nustrini Papakura Aeroplane fabriced. -

Live the Backcountry Adventure— Homebuilt Style!

BUILDER SHORTCUTS BIG-SCREEN ADVICE Should you buy a partially built kit? How to plan your EFIS installation get LiveOut! the backcountry adventure— homebuilt style! NOVEMBER 2005 New Life for a www.kitplanes.com $4.99 CANADA $5.99 $4.99US $5.99CAN Classic Design Engine 11 The SkyRanger II Preservation: Pickle Before See Clearly Now You Park 0 09281 03883 2 Plexiglas Care & Feeding 101 Contents NOVEMBER 2005 VOLUME 22, NUMBER 11 On the cover: Richard VanderMeulen traveled to the Alaskan backcountry to shoot Glasair Aviation’s Sportsman 2+2. Read Brian E. Clark’s trip report on Page 4. Flight Reports 61 AERO ’LECTRICS If it’s not your transmitter, then it must be your 4 SIX PILOTS, THREE AIRPLANES, antenna; by Jim Weir. ONE GREAT ADVENTURE 72 ENGINE BEAT Flying through Alaska and Western Canada is a once- Pickle it when you park it; by Tim Kern. in-a-lifetime experience; by Brian E. Clark. Designer’s Notebook 17 SKYRANGER II 67 WIND TUNNEL A new take on a classic design makes for fun fl ying; Neglect to consider internal airfl ow, and you’ll by Dave Higdon. pay the price in drag; by Barnaby Wainfan. Builder Spotlight Exploring 37 HOW TO PROWL THE HOMEBUILT JUNGLE 2 AROUND THE PATCH Consider these fi ve factors when evaluating a Recovery from Oshkosh. Good thing we do that partially built kit; by Ron Wanttaja. just once a year! By Marc Cook. 48 LACK OF CORNCENTRATION 24 OSHKOSH 2005: BIG NEWS FROM THE BIG SHOW Another Dawn Patrol trip to Cap Girardeau, and an The developments at this year’s AirVenture fl y-in other airplane ends up in the stalks; by Dick Starks. -

EAA Webinars Are Supported By

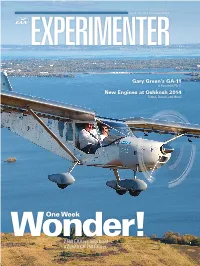

Vol.3 No.10 I October 2014 The Spirit of Homebuilt Aviation I www.eaa.org Gary Green’s GA-11 A Homebuilt PA-11 New Engines at Oshkosh 2014 Turbos, Diesels, and More! Wonder!One Week 2,500 EAAers help build a Zenith CH 750 Cruzer EEAAEXP_Oct14.inddAAEXP_Oct14.indd 1 110/20/140/20/14 22:45:45 PPMM TOWER FREQUENCY EAA, We Are Builders BY JACK J. PELTON BUILDING OUR OWN airplanes was a founding activity of think back a few years and you can see how far we EAA. But we build so much more. And it is building, main- have come. taining, restoring, and preserving that separates EAA from And we build airplanes. Construction of the Zenith kit other associations. during the week of Oshkosh by hundreds and hundreds of Our most impressive building is, of course, our world volunteers created new excitement for so many. The proj- class museum. There is no better collection of important ect was dubbed the One Week Wonder, but it was not really private and sport airplanes. And our Eagle Hangar honors a wonder. I never doubted for a moment that the project all who served with an impressive display of World War II would be completed, engine run, and airplane taxied before airplanes and artifacts. the end of our convention. Pioneer Airport is the active component of our museum. All of this activity goes back to our founder, Paul Pober- Its hangars and turf runway accurately re-create a typical ezny. Paul’s founding belief that he repeated over and over airport of the golden age. -

Aircraft Owners Seeking Full Formotion COPA Hull and MEMBERS—Liability Coverage

THE JOURNAL OF THE CANADIAN OWNERS AND PILOTS ASSOCIATION REGIONS | BRITISH COLUMBIA COPATKTKT KT KTKT FLIGHT WatER SEptEMBER 2016 IN MARS OSHKOSH StAR PERFORMER UNDERGOING HULL REPAIRS MORE THAN 80 AIRPLANES FOR SALE 9-11 NO MEDIcaL B-17 TOURS PILotS SOUVENIR CHANGES THE WEST N PawS FREEDOM TO FLY CANADA Won’T HISTORY PILOTS WITH BROUGHT HOME FOLLOW U.S. COMES ALIVE A CAUSE NAVITIMER COPA Limited Edition Breitling proudly launches the Navitimer World COPA, a 50-piece limited edition chronograph honoring the Canadian Owners and Pilots Association and perfect for global flight. The Breitling Navitimer has been a favorite among pilots and aviation enthusiasts since it was introduced in 1952 – the same year that COPA was founded. Powered by a COSC-certified selfwinding chronograph movement, this new and exclusive addition to the Navitimer series paying tribute to COPA’s contribution to general aviation features a dial and caseback showcasing the COPA logo. BREITLING.COM COPA_NavitimerGMT_8,5x11inches-BR17480.indd 1 30/05/2016 11:30 COPAFLIGHT EDITOR Russ Niles [email protected] CONTENTS 250.546.6743 GRAPHIC DESIGN Shannon Swanson PRODUctION Gordon Fidler COPY EDITOR Scott Simmons ADVERTISING SALES Katherine Kjaer 250.590.5331 [email protected] CIRCULATION Diana Topping AccOUNTING Anthea Williams ASSISTANT ADMIN Rajei Gill COPA BOARD Bernard Gervais, President and CEO Executive Committee Jean Messier Chair, Quebec Director Bram Tilroe Western Vice-Chair, Alberta & NWT Director Brian Chappell Feature Departments Eastern Vice-Chair, Maritimes Director Jim Bell 5 PRESIDENT’s CORNER Secretary, Manitoba & Nunavut Director 37 CANADIAN Medical Disconnect Jonathan Beauchesne CONTENT Treasurer, Quebec Director 8 MAILBOX Canadians were front and centre First Female Pilot Elected Directors at AirVenture 2016 in Oshkosh and they didn’t disappoint. -

200412-2004 Quad City Challenger.Pdf

which several of the players gather on the mound in the middle of the game. Kevin Costner, playing the lead character, reminds his teammates that, in the Inend,thetheymovieall playBull baseballDurham,becausethere is"it'sa classicfun, dammit."scene in It is a reminder not to take themselves, or the game, too seri• ously, and it reminds everyone how Costner's character has lasted for so many years playing minor league baseball. It sure isn't the money. That mindset carries over to flying as well. For all the rea• sons that we conjure up for learning to fly, be it to utilize an airplane for business, to save time, to travel to exotic locales, or for the sake of building a career, the only thing that can ul• timately keep someone coming back to the airport is that fly• ing is fun. We just need to be reminded every once in a while. There are various ways to recapture the fun in flying. Some pilots take up soaring; some pursue a tailwheel endorsement; some splurge on a helicopter rating. And then there is ultra• light flying. Art Kudner and Dan Wroe, both 40 years old, are dealers for the Quad City Challenger, an ultralight that oper• ates on both wheels and on amphibious floats. The Chal- The view from here Ultralights and the love of flying BY CHIP WRIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHAEL P. COLLINS lenger is a high-wing ultralight with a tube structure covered in Ceconite, and an excellent overall safety record. I was able to get a ride on Kudner and Wroe's Challenger demonstrator in 2001, and they recently invited my father and me to try a more extensive flight to get an honest feel for what might be required to comfortably-and safely-solo one. -

Example TADS

LAA TYPE ACCEPTANCE DATA SHEET TADS 177 - QUAD CITY CHALLENGER II TADS 177A - BFC CHALLENGER II TADS 177B - BFC CHALLENGER II S.E. LONGWING Control range of movements updated & Issue 2 Dated 08/10/18 JP clarification of flap indicator requirement Revision A Addition of Safety Spot articles. Dated 02/12/19 MR This TADS is intended as a summary of available information about the type and should be used during the build, operation and permit revalidation phases to help owners and inspectors. Although it is hoped that this document is as complete as possible, other sources may contain more up to date information, e.g. the manufacturer’s website. Section 1 contains general information about the type. Section 2 contains information about the type that is MANDATORY and must be complied with. Section 3 contains advisory information that owners and inspectors should review to help them maintain the aircraft in an airworthy condition. If due consideration and circumstances suggest that compliance with the requirements in this section can safely be deferred, is not required or not applicable, then this is a permitted judgement call. This section also provides a useful repository for advisory information gathered through defect reports and experience. Section 1 - Introduction 1.1 UK contact There is no UK based contact for the aircraft. The Quad City Aircraft factory can be contacted at: Tel: +01 309 76 3515 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.qcaircraft.com/index.php Address: Quad City Aircraft Corp 3810 34th Street Moline, IL 61265 USA There are some online owner based forums that may provide useful reference information including Challenger BTT and Quad City Ultralight Challenger Yahoo Group. -

N# Builder Model S/N CITY STATE 19883 TAYLOR

N# Builder Model S/N CITY STATE 19883 TAYLOR-YOUNG "A" 388 AVOCA NE 386SJ THOMPSON RJ/ABENDROTH HJ # 1 110 TUCSON AZ 835LL LUDWIG LARRY E #1 BUSH 109 LEWISTON ID 511JT MARTIN JOE $6-E$116 1292412JM BROKEN ARROW OK 207EN WHITMAN BRUCE R (M-1) MIDGET MUSTANG 06 LOWELL MI 1141G EWERT PAUL 001 CONDOR 2 001 HOT SPRINGS SD 55AN NEILL LESTER ACE 002 1993 TULSA OK 53AN NEILL LESTER A 003 1970 PORTLAND TN 301AH HARMENINGS HIGH FLYERS 006009 6009 DE YOUNG PA 196K HARMENING HIGH FLYERSHIGHFLYER 006144 6009 EDINBORO PA 343N HELMBOLDT DANDEE 010 0329 FORT WORTH TX 32951 JAMES E DUNCAN 069 042249 VENICE FL 4366T EMICH MICHAEL 1 1 SAN ANTONIO TX 91904 EPPERSON EDWIN R 1 61 WACO TX 1010C RAYNER CURTISS PUSHER 1 113 MONON IN 7082D STRICKLER STEVEN M 1 0047 IOLA KS 66447 SWANK ROBERT K 1 1 FOUNTAIN CO 100SJ WILDS WYMOND A 1 PASSENGER SJ-001 PAHOA HI 238SK TREADWELL WALTER L 1/2 SCALE S38 005 WALNUT CREEK CA 483SG DONALD R GUTZMER 100 01 BEAVERTON MI 101K PZL 101 119259 LONOKE AR 136LS AEROLITE/DOUGLAS SEAN P 103 A-AWI-112102-124LAKELAND FL 491H GENERAL AIRCRAFT CORP. 111-C 2 FELTON DE 80XP AERO DESIGN ELEVEN 12 0001 SANTA BARBARA CA 415GC GRECO AIR INC 12 300 WILMINGTON DE 360TK JIM KIMBALL ENTERPRISES INC 12 272 WELLSVILLE PA 288X ODELL BOB 120-88 001 FORESTHILL CA 867TG TUMBLING GOOSE LLC 12S 353 MILAN MI 160WS GERARD J GROSS 13 METER WOODSTOCK 1 STATE COLLEGE PA 950RS SMITH ROBERT V 1300Z MK364 DENVER CO 96VR VAUGHN ROBERT L 1400 MK776 TELL CITY IN 20912 B/G DART 150 1 PORT CLINTON OH 2510P MAX HOLSTE 1521 283 FAIRBANKS AK N# Builder Model S/N CITY STATE -

LAA Technical Leaflet TL 3.17 Specific Type Mod Title Description Engine Engine Model Reg Number Manufacturer ACRODUSTER 2 14500 FUEL SYSTEM CHANGE

LAA Technical Leaflet TL 3.17 Specific type Mod Title Description Engine Engine model Reg number manufacturer ACRODUSTER 2 14500 FUEL SYSTEM CHANGE . LYCOMING IO-360-A1A BLES ACRODUSTER 2 14646 2 PLACE CANOPY FACTORY-SUPPLIED 2-PLACE SLIDE-AND-LIFT CANOPY INSTALLED. SUPPLEMENTAL ENGAGEMENT LYCOMING IO-360-A1A BLES POINTS HAVE BEEN ADDED: TWO ON THE COAMING BETWEEN THE TWO SEATS (WITH ADDITIONAL STIFFENERS) AND ONE TO THE REAR OF THE P1 POSITION. PINS ATTACHED TO THE CANOPY ENGAGE IN THESE RECEPTACLES, PROVIDING LOAD PATHS TO THE AIRFRAME FOR VERTICAL LOAD COMPONENTS. MECHANISMS ARE PROVIDED TO ENABLE THE CANOPY TO BE OPENED FROM EITHER SEAT POSITION AND FROM OUTSIDE THE AIRCRAFT. ACRODUSTER TOO SA750 14241 PROPELLER CHANGE TO SENSENICH PROPELLER CHANGE TO W76HM8-54 76" X 54" PROPELLER. LYCOMING IO-360-A1B6 CEZK W76HM8-54 ACROSPORT 1 14069 PROPELLER CHANGE TO HERCULES INSTALLATION OF HERCULES 7255458-S 72 INCH DIAMETER X 55 INCH PITCH PROPELLER. LYCOMING O-290-D BTWI 7255458-S ACROSPORT 1 14552 MAIN UNDERCARRIAGE SUSPENSION INSTALLATION OF M-222-100 SPRING TYPE MAIN UNDERCARRIAGE SHOCK STRUTS IN DIRECT LYCOMING O-290-D BTWI SHOCK STRUTS INSTALLATION REPLACEMENT OF BUNGEE SHOCK STRUTS. ACROSPORT 2 11962 INVERTED FUEL AND OIL SYSTEM FIT PART 1 - RAVEN INVERTED OIL SYSTEM INSTALLATION. ECI TITAN EXP O-360- BKCV PART 2 - ELLISON EFS4-5 THROTTLE BODY INJECTION SYSTEM INSTALLATION. D1A1N NOTE: G-BKCV APPROVED FOR PART 1 ONLY. ACROSPORT 2 13363 CRANKSHAFT END BOLT CHANGE STEEL DOUBLE-THREADED THREAD REDUCTION INSERT USED IN STANDARD 'THICK WALLED' LYCOMING O-360-A1A CGAK CRANKSHAFT END TO ENABLE USE OF 180HP GEAR WHEEL. -

2006 Kit Buyer's Guide

343 NEW KITS FOR SALE! BUY USED BUT BE SMART Is your next plane one of them? Lycoming O-320 & O-360 Gotchas 2006 Kit Buyer’s Guide All Your Questions Answered! HOW FAST ? HOW BIG ? HOW MANY FLYING ? HOW MUCH ? DECEMBER 2005 P&W Turbine Engine & www.kitplanes.com $4.99 CANADA $5.99 Amphib Floats! XCOM’s 760 Radio: The T-Moose Makes a Big Splash Tiny Platform, The Excalibur II Huge Feature List Is It Up to the Challenger? Engineered to exceed expectations. Engineered for you. Introducing the AuRACLE TM by Xerion Avionix. The new AuRACLE TM advanced engine management system integrates critical functionality with affordability. The Xerion AuRACLE TM incorporates a brilliant 5.0” Active Matrix LCD display, using the latest in surface treatment 188 InHg AuRACLE HP 22.3 fi lms, to bring you the brightest and easiest to read engine 66 2350 RPM monitor on the market. The AuRACLE’sTM revolutionary %HP 13.4 Gal/Hr display presents the MAP, RPM, and FF data in a layout 1503 °F 65.2 1900 -93 °F LOP 500 OP - PSI similar to cockpit controls. The graphic design, which displays 180 OT - °F the critical information at all times, quickens your scan and TM TM 385 4.7 reduces your workload. The AuRACLE SmartLean Vac - InHg system guides you through the leaning process ROP or LOP 46.3 Gal +4.0 TM Fuel Rem Amps by sensing your actions. Once leaned, the AuRACLE 3:26 26.6 provides you with a continuous status of the Leanest/Richest Time Rem 800 123456 200 Volts TIT EGT CHT TM 1:15 1476 °F 1410 °F 368 °F 30 46 cylinder. -

Ultralight Aircraft to Place Your Ad in 1 Time $188 • 3 Times @ $177 Ea

Aventur a ii It’s a Bird! It’s a Boat! No…it’s a HOOT! JULY 2006 Big Feet, Little Feat Gear Maintenance Made Easy $4.99US $5.99CAN Flying to a Fly-In: 07 Sun ’n Fun 2006 All the News From Lakeland What You Can Do Odyssey of the Young To Make It Safer 0 09281 03883 2 Levi Self is 15—and a Builder airPlay. The Lancair Legacy. Acceleration meets exhilaration. You climb at a rate of 2500 fpm to 10,000 feet, level off, then swallow up a 1200 mile route at 280 mph on a single tank of gas. You want to pinch yourself. But you are not dreaming. No, you are flying, first class, in the sleek Lancair Legacy—a combination of speed, control, comfort and economy that translates into unparalleled performance and pure flying fun. There is also an extra measure Cruise 280 mph Useful Load 800 Lbs of satisfaction that comes from having built this beauty yourself. And with simple, Range 1200 miles straightforward instructions as well as optional one-week to eight-week builder’s Stall Speed 67 mph Rate of Climb 2500 fpm assistance programs you can dramatically cut the time to that first flight in your Horsepower 310 new Legacy. Fuel Burn 15 GPH The Lancair Legacy and the fixed-gear Legacy FG. Two aeronautical masterpieces that deserve serious airPlay. Lancair-Kits.com ■ 541.923.2244 Performance from the Ground Up Copyright © 2005 Neico Aviation Inc. All rights reserved, specifications and pricing to change without notice. Photograph by Mark Leet Photography. -

Buying a Used Homebuilt Cost-Of-Flying Special

COST-OF-FLYING SPECIAL BUYING A USED HOMEBUILT You can build an airplane for $40,000! What to ask before you put down the cash! KITPLANES J 2005 Sil T i t C t f Fl i S i l S ti Th P f t P i t J b P t 2 B ild Y O I t t P l BELVOIR PUBLICATIONS $4 99 CANADA $5 99 ® JUNE 2005 Twister!www.kitplanes.com $4.99 CANADA $5.99 Oh, You Make Flying Fun $4.99US $5.99CAN Specialized 06 BUILD YOUR OWN PANEL Training: Part 1 of a New Series To Save You $$$ FAST TIMES at PERFECT PAINT #2 LANCAIR HIGH 0 09281 03883 2 We Continue Our Series On DIY Finishes ©2004 Garmin Ltd or its subsidiaries Skyways, highways, waterways, anyways. Garmin brings new versatility to its family of aviation portables. When it’s all about traveling fast and light, these are the go-to guides you’ll want. Check out our new do-it-all “Palm Pilot® for real pilots” – the iQue 3600a PDA/GPS. It features a vivid color moving map, plus a snap-in yoke mount with aviation function keys. Much like our fast-selling GPSMAP® 296 portable, it gives you TAWS-like terrain alerting. And there’s a towers-and-obstacles database with map overlays – which you’ll also find on our grayscale or color GPSMAP 96/96C handhelds. All units, including the grayscale GPSMAP 196, offer graphic HSI steering with GPS-derived VNAV.And optional MapSource® downloads let you go from plane to boat to automobile without missing a beat.