Calder in France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calder and Sound

Gryphon Rue Rower-Upjohn Calderand Sound Herbert Matter, Alexander Calder, Tentacles (cf. Works section, fig. 50), 1947 “Noise is another whole dimension.” Alexander Calder 1 A mobile carves its habitat. Alternately seductive, stealthy, ostentatious, it dilates and retracts, eternally redefining space. A noise-mobile produces harmonic wakes – metallic collisions punctuating visual rhythms. 2 For Alexander Calder, silence is not merely the absence of sound – silence gen- erates anticipation, a bedrock feature of musical experience. The cessation of sound suggests the outline of a melody. 3 A new narrative of Calder’s relationship to sound is essential to a rigorous portrayal and a greater comprehension of his genius. In the scope of Calder’s immense œuvre (thousands of sculptures, more than 22,000 documented works in all media), I have identified nearly four dozen intentionally sound-producing mobiles. 4 Calder’s first employment of sound can be traced to the late 1920s with Cirque Calder (1926–31), an event rife with extemporised noises, bells, harmonicas and cymbals. 5 His incorporation of gongs into his sculpture followed, beginning in the early 1930s and continuing through the mid-1970s. Nowadays preservation and monetary value mandate that exhibitions of Calder’s work be in static, controlled environments. Without a histor- ical imagination, it is easy to disregard the sound component as a mere appendage to the striking visual mien of mobiles. As an additional obstacle, our contemporary consciousness is clogged with bric-a-brac associations, such as wind chimes and baby crib bibelots. As if sequestered from this trail of mainstream bastardi- sations, the element of sound in certain works remains ulterior. -

RECENT ACQUISITIONS Dear Friends and Collectors

WALLY FINDLAY GALLERIES RECENT ACQUISITIONS Dear Friends and Collectors, Wally Findlay Galleries is pleased to present our most recent e-catalogue, Recent Acquisitions, featuring the newest additions to our collection. The catalogue features works by Aizpiri, Berthelsen, Brasilier, Cahoon, Calder, Cassignieul, Chagall, D’Espagnat, Jean Dufy, Gen Paul, Hambourg, Hervé, Indiana, Kluge, Leger, Le Pho, Miró, Outin, Sébire, Sipp-Green, Simbari, Simkohvitch, and Vu Cao Dam. For further information in regards to these works and the current collection, please contact the New York gallery. We look forward to hearing from you. WALLY FINDLAY GALLERIES 124 East 57th Street, New York, NY (212) 421 5390 [email protected] Aïzpiri Paul Aïzpiri (b. 1919) was born in Paris on May 14, 1919. Aïzpiri entered l’École Bulle to learn antique restoration, after his father insisted that he first learn a trade as a means of assuring his livelihood. After the course he entered the Beaux-Arts to study painting. Aïzpiri was certainly encouraged as a young painter in his early 20’s, during somber war-torn France, exhibiting amongst the painters of l’École Pont-Aven and the Nabis. He became a member of the Salon d’Automne in 1945, won Third Prize at the Salon de Moins de Trente Ans, of which he was a founding member and later showed at the Salon “Les Peintres Témoin de leur Temps”. In 1948, Aïzpiri won the Prix Corsica which allowed him to go to Marseilles. His stay there so impressed him, that he declared it was a turning point of his art. Not only did he find a whole new world to paint which was far different subjectively from any life he had known in Paris, but also a new world of color. -

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney Author Sweeney, James Johnson, 1900-1986 Date 1943 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2870 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE MUSEUM OF RN ART, NEW YORK LIBRARY! THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Received: 11/2- JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY ALEXANDER CALDER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK t/o ^ 2^-2 f \ ) TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; McAlpin*, William S. Paley, Mrs. John Park Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ist Vice-Chair inson, Jr., Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Beardsley man; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice-Chair Ruml, Carleton Sprague Smith, James Thrall man; John Hay Whitney*, President; John E. Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg*. Abbott, Vice-President; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President; Mrs. David M. Levy, Treas HONORARY TRUSTEES urer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Mur ray Crane, Marshall Field, Philip L. Goodwin, Frederic Clay Bartlett, Frank Crowninshield, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Duncan Phillips, Paul J. Sachs, Mrs. John S. Henry R. Luce, Archibald MacLeish, David H. Sheppard. * On duty with the Armed Forces. Copyright 1943 by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York Printed in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Black Dots, 1941 Photo Herbert Matter Frontispiece Mrs. Whitney Allen, Rochester, New York; Collection Mrs. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Alexander Calder Biography Born in 1898, Lawnton, PA. Died in 1976, New York, NY. Education: 1926 Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Paris, France. 1923–25 Art Students League, New York, NY. 1919 B.S., Mechanical Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ. Solo Exhibitions: 2015 Alexander Calder: Imagining the Universe. Sotheby’s S|2, Hong Kong. Calder: Lightness. Pulitzer Arts Foundation, Saint Louis, MO. Calder: Discipline of the Dance. Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico. Alexander Calder: Multum in Parvo. Dominique Levy, New York, NY. Alexander Calder: Primary Motions. Dominique Levy, London, England. 2014 Alexander Calder. Fondation Beyeler, Basel. Switzerland. Alexander Calder: Gouaches. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. Alexander Calder: Gouaches. Gagosian Gallery, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, NY. Alexander Calder in the Rijksmuseum Summer Sculpture Garden. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. 2013 Calder and Abstraction: From Avant-Garde to Iconic. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA. 2011 Alexander Calder. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. 2010 Alexander Calder. Gagosian Gallery, W. 21st Street, New York, NY. 2009 Monumental Sculpture. Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. 2005 Monumental Sculpture. Gagosian Gallery, W. 24th Street, New York, NY. Alexander Calder 60’s-70’s. GióMarconi, Milan, Italy. Calder: The Forties. Thomas Dane, London, England. 2004 Calder/Miró. Foundation Beyeler, Riehen, Switzerland. Traveled to: Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. (through 2005). Calder: Sculpture and Works on Paper. Elin Eagles-Smith Gallery, San Francisco, CA. 590 Madison Avenue, New York, NY. 2003 Calder. Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Calder: Gravity and Grace. -

Alexander Calder - Amílcar Pereira De Castro - David Oliveira)

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES A ESSÊNCIA DA LINHA E DO DESENHO PARA A ESCULTURA (Alexander Calder - Amílcar Pereira de Castro - David Oliveira) Célia Cristina de Siqueira Cavalcanti Veras Dissertação Mestrado em Escultura Especialidade em Estudos de Escultura 2015 1 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES A ESSÊNCIA DA LINHA E DO DESENHO PARA A ESCULTURA (Alexander Calder - Amílcar Pereira de Castro - David Oliveira) Célia Cristina de Siqueira Cavalcanti Veras Dissertação Mestrado em Escultura Especialidade em Estudos de Escultura 2015 2 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES A ESSÊNCIA DA LINHA E DO DESENHO PARA A ESCULTURA (Alexander Calder - Amílcar Pereira de Castro - David Oliveira) Célia Cristina de Siqueira Cavalcanti Veras Dissertação orientada pelo Professor Associado com Agregação António José Santos de Matos Mestrado em Escultura Especialidade em Estudos de Escultura 2015 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Ao professor António Matos, pela orientação, amizade e momentos de descontração com a renovação de forças para continuidade dessa pesquisa. Agradeço a minha mãe, Carmen-Lúcia de Siqueira Cavalcanti Veras, pelas suas preces e por estar sempre presente mesmo na distância, a minha irmã-mãe, Lúcia Maria de Siqueira Cavalcanti Veras, por quem tenho profunda admiração, que me acolhe, apoia e colabora em tudo. Ao meu filho Hugo Veras Dencker, por quem tenho incondicional amor, a compreensão pela minha ausência física, que será recompensada. Agradeço a todos os meus professores do Mestrado da Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade de Lisboa. Aos meus cunhados, José Martins e Maria Nazaré, pelo apoio, carinho e momentos em família e por fim e principalmente, ao meu marido Eduardo Cardoso Filho, por ter me proporcionado, incentivado e cooperado de todas as maneiras possíveis com seu amor e companheirismo. -

![Archivision Art Module E[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9475/archivision-art-module-e-1-1349475.webp)

Archivision Art Module E[1]

ARCHIVISION ART MODULE E: WORLD ART III 3000 photographs | images available now | data to come summer 2020 CANADA Montreal Montreal Museum of Fine Arts: Chagall Exhibit • Juggler with a Double Profile (1968) [1] • King David (1954) [3] • Rooster (1947) [5] • Sketch for Clown with Shadow (1964) [1] • Sketch for Comedia dell'arte (1957-58) [1] • Rainbow (1967) [3] • Red Circus (1956-1960) [3] • Triumph of Music (final model for Lincoln Center) (1966) [11] • Triumph of Music (prep drawing 1 for Lincoln Center) (1966) [1] • Triumph of Music (prep drawing 2 for Lincoln Center) (1966) [1] • Wedding (1944) [3] • Variation on the theme of The Magic Flute - Sarastro (1965) [4] • Variation on the theme of The Magic Flute - Papageno (1965) [3] • La Pluie (Rain) (on loan from S. Guggenheim Museum, 1911) Montreal Museum of Fine Arts: Napoleon Exhibit • Apotheosis of Napoleon I, by workshop of bertel Thorvaldsen (ca. 1830) [8] • The Last Attack, Waterloo, Ernest Crofts (1895) [17] Montreal Museum of Fine Arts: Picasso Show • Malanggan Ceremonial Carving (New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, 20th century) [1] • Yupik Finger Mask from Alaska (19th century) [1] • Kavat mask, by baining artist (Papua New Guinea), before 1965 [2] • Headdress, Unknown Tusian (Tusyan) artist (burkina Faso) 20th C [3] • blind Minotaur Guided by Little Girl in the Night (1934) [1] • Bouquet of Flowers [1] • Figure (1930) [1] • Head of a Woman (1927) [1] • Head of a Woman 2 (1929) [1] • Head of a Young Woman (1945) [1] • Large Reclining Nude (1943) [2] • Portrait of a Woman [1] by -

MW5 Layout 10

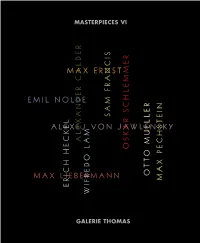

MASTERPIECES VI GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES VI MASTERPIECES VI GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS ALEXANDER CALDER UNTITLED 1966 6 MAX ERNST LES PEUPLIERS 1939 18 SAM FRANCIS UNTITLED 1964/ 1965 28 ERICH HECKEL BRICK FACTORY 1908 AND HOUSES NEAR ROME 1909 38 PARK OF DILBORN 191 4 50 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY HEAD OF A WOMAN c. 191 3 58 ABSTRACT HEAD: EARLY LIGHT c. 1920 66 4 WIFREDO LAM UNTITLED 1966 76 MAX LIEBERMANN THE GARDEN IN WANNSEE ... 191 7 86 OTTO MUELLER TW O NUDE GIRLS ... 191 8/20 96 EMIL NOLDE AUTUMN SEA XII ... 191 0106 MAX PECHSTEIN GREAT MILL DITCH BRIDGE 1922 11 6 OSKAR SCHLEMMER TWO HEADS AND TWO NUDES, SILVER FRIEZE IV 1931 126 5 UNTITLED 1966 ALEXANDER CALDER sheet metal and wire, painted Provenance 1966 Galerie Maeght, Paris 38 .1 x 111 .7 x 111 .7 cm Galerie Marconi, Milan ( 1979) 15 x 44 x 44 in. Private Collection (acquired from the above in 1979) signed with monogram Private collection, USA (since 2 01 3) and dated on the largest red element The work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York under application number A25784. 8 UNTITLED 1966 ALEXANDER CALDER ”To most people who look at a mobile, it’s no more time, not yet become an exponent of kinetic art than a series of flat objects that move. To a few, in the original sense of the word, but an exponent though, it may be poetry.” of a type of performance art that more or less Alexander Calder invited the participation of the audience. -

New Sanctuary Dedicated to Art of Alexander Calder to Open in Heart of Downtown Philadelphia on Benjamin Franklin Parkway

NEW SANCTUARY DEDICATED TO ART OF ALEXANDER CALDER TO OPEN IN HEART OF DOWNTOWN PHILADELPHIA ON BENJAMIN FRANKLIN PARKWAY Herzog & de Meuron Selected to Design New Cultural Space With Bespoke Exhibition Galleries and Gardens that Foster Introspective Experiences And Support Education with Masterworks from Calder Foundation Left: Portrait of Calder, c. 1930. Photo: Man Ray. © 2020 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; © 2020 Man Ray Trust / ADAGP. Right: Alexander Calder, Untitled, c. 1952. © 2020 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Philadelphia, PA — February 20, 2020—A new sanctuary dedicated to the art of Alexander Calder, one of the most innovative artists of the 20th century, will be created in the heart of downtown Philadelphia. Herzog & de Meuron has been selected to design the new cultural facility, which will feature bespoke galleries and gardens presenting a rotating selection of masterworks from the Calder Foundation, including mobiles, stabiles, monumental sculptures, and paintings. The nonprofit initiative, which will be formally named in the coming months, has been launched by a group of Philadelphia philanthropists working in collaboration with the Calder Foundation and in partnership with the City of Philadelphia and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Tuned specifically for the presentation of Calder’s work, the spaces and gardens will unfold as a choreographed progression that will move viewers beyond the traditional museum experience to engage with the work in the way the artist intended—as a personal, real-time encounter. The facility will include opportunities to explore works by Calder’s parents, the artists Alexander Stirling Calder and Nanette Lederer Calder, and his grandfather Alexander Milne Calder, all of whom had deep ties to Philadelphia. -

A Semiótica Da Escultura Antonio Vicente Seraphim Pietroforte*

estudos semióticos www.revistas.usp.br/esse issn 1980-4016 vol. 14, no 1 março de 2018 semestral p. 144–157 A semiótica da escultura Antonio Vicente Seraphim Pietroforte* Resumo: Ao que tudo indica, a semiótica narrativa e discursiva proposta por Greimas e colaboradores tem, além de sua vocação teórica, tendência de ser testada em aplicações analíticas nos mais variados tipos de discurso e sistemas de significação. Desde os primeiros trabalhos de divulgação científica, isso está presente: em Introdução à semiótica narrativa e discursiva, de J. Courtés – tradução para o Português de 1979 –, há análises do conto de fadas da Cinderela; em Semiótica da narrativa, de N. Everaert-Desmedt – tradução para o Português de 1984 –, há análises dos Labirintos de Espelhos e Trens Fantasmas dos parques de diversões. Ora, essa vocação, na análise das artes plásticas, certamente tem em Jean-Marie Floch um de seus mais criativos representantes; Floch é célebre por suas aplicações da semiótica no estudo do cinema, do teatro, da pintura, da fotografia, da história em quadrinhos, da arquitetura, do discurso publicitário. Quanto à análise da escultura, comparada à análise dos demais sistemas de significação, pouco foi dito. Desse modo, buscando preencher essas lacunas, nosso trabalho vai ao encontro da aplicação da semiótica à análise da escultura em duas frentes: a escultura enquanto texto; a escultura enquanto objeto de valor. Palavras-chave: semiótica, texto, discurso, artes plásticas, escultura A semiótica de escultura começa, necessariamente, com a escolha da teoria utilizada em sua abordagem: se a opção é a semiótica de Charles Sanders Peirce, a escultura é descrita por meio de relações entre signos, responsáveis pela significação da escultura em meio a essas redes de relações; se a opção é a semiótica de Algirdas Julien Greimas, a escultura é entendida en- quanto texto, sua significação se realiza em processos narrativos e discursivos. -

New Rooms Art & the Spanish Civil War Collection

ENG NEW ROOMS ART & THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR COLLECTION ART FIRST FLOOR AND CIVIL WAR ROOMS 76 - 80 The Museu Nacional renews its exhibition discourse, and at the same time 83 49 extends the number of rooms dedicated to the art produced during the 79 43 Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Painting, sculpture, drawing and engraving, along with new types of me- 77 78 39 41 42 45 48 50 dia, such as illustrated publications, posters, photography, photomontage and cinema, were put to use on both sides. Dome During the war years, many artists decided not to remain neutral: art be- 76 80 Hall 40 44 46 47 51 came a powerful weapon for stirring consciences and gaining support for one political cause or another. Despite the dramatic circumstances, this mobilisation was the culmina- 52 tion of some of the aspirations in modern art and the avant-garde. Using the 64 war as a motive, an entire iconographic programme unfolded, where themes 59b 56 53 such as the war front, aerial bombardments, and massacres and evacua- PAVILION OF THE REPUBLIC VICTIMS AND EXECUTIONERS tions of the civilian population were singled out. PROPAGANDA WOMEN ARTISTS IN TIMES OF WAR HEROES AND HEROINES69 67 66 EVACUATION65 63 62 61 60 59 58 57 55 70 54 [Cover] Room 76 Andrés Fernández Cuervo Sierra. Bombing. Detail, 1937 From the International Exhibition in Paris, 1937 Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya Room 78 Helios Gómez. Evacuation, 1937 Room 76 Loan from Gabriel Gómez Plana, son of the artist, 2003 Juana Francisca Rubio. Hero, c. -

Packet 12.Pdf

LONE STAR Head Edited by Daniel Ma. Edited by Daniel Ma, Thomas Gioia, Michael Yue, Roman Madoerin, Dr. Eric Mukherjee, Robert Condron, Sean Doyle, and Michael Patison. Written by the editors, Jisoo Yoo, Johnny Vasilyev, Nikita Nair, Aayush Goodapaty, Josh Rubel, Ketan Pamurthy, Ned Tagtmeier, Akshay Shyam, and Michael Artlip. Playtested by Dean Ah Now, Hari Parameswaran, and Rohan Venkateswaran. Packet 12 Only read this packet if the last tossup of the previous round was Faust. TOSSUP 1 In an interview, this man confirmed that one of his films is a sequel to Being John Malkovich, but denied that Rod imagined its events. In that film, Chris Washington kills Dean Armitage with the head of a deer. In another of his films, Adelaide is choked in the hall of mirrors, and Jason’s (*) doppelganger walks on all fours. In one sketch, this man plays a student named Timothy. This man appeared in comedy sketches such as the East/West College Bowl with Keegan-Michael Key. For 10 points, name this man who wrote and directed Us and Get Out. ANSWER: Jordan Peele <Goodapaty> BONUS For 10 points each, name these specific climatic regions. [10] Name this semiarid region that stretches east to west across an entire continent for over 3500 miles. It includes pastures with scattered baobabs and acacias and is under substantial desertification pressure. ANSWER: Sahel [10] The desert north of the Sahel is this desert, the world’s largest, in North Africa. ANSWER: Sahara Desert [10] The more wooded area south of the Sahel is often given this name, translating as “Land of the Blacks.” A country with this name includes the Darfur region, a site of ongoing conflict since 2003. -

Sache, France Roxbury, CT

Sache, France Roxbury, CT 1 Young Alexander Calder, date, photograph Calder is probably one of the most well-known sculptors of the 20th century. He is credited with creating several new art forms – the MOBILE and the STABILE He was born on July 22, 1989 just outside of Philadelphia. Alexander Calder, known to his friends as Sandy. He was a bear of a man with a good nature, a good heart and a vivid imagination. He always wore a red flannel shirt, even to fancy events. Red was his favorite color, “I think red’s the only color. Everything should be red.” 2 Alexander Calder and his father Alexander Stirling Calder, c. 1944, photograph He came from a family of artists. His mother was a well-known painter and his father and grandfather were also sculptors and were also named Alexander Calder – they had different middle names. 3 Ghost, 1964, Alexander Calder, metal rods, painted sheet metal, 34’ , Philadelphia Museum of Art In Philadelphia you can see sculpture from 3 generations of Calders. o Ghost created by Alexander Calder hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the Grand Hall. 4 Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Square, Alexander Stirling Calder, 1924 o Further down the street is the Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Square created by his father, Alexander Stirling Calder. 5 William Penn, Alexander Milne Calder, 1894, size, Philadelphia City Hall o Even further down the street on the top of Philadelphia’s City Hall is the statue of William Penn made by his grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder. 6 Alexander Milne Calder, date, photograph 1849‐1923 –Calder’s grandfather 7 Circus drawing done on the spot by Calder, in 1923, thanks to his National Police Gazette pass He moved around a lot as a child, but he always had a workshop wherever he lived He played with mechanical toys and enjoyed making gadgets and toy animals out of scraps.