Chapter 5 — Heat-Clearing Formulas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unnatural Amino Acid Incorporation to Rewrite The

Unnatural Amino Acid Incorporation to Rewrite the Genetic Code and RNA-peptide Interactions Thesis by Xin Qi In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 2005 (Defended May 19, 2005) ii © 2005 Xin Qi All Rights Reserved iii Acknowledgments I like to sincerely thank my advisor, Dr. Richard W. Roberts, for his great mentorship over the course of my graduate career here at Caltech. This thesis would have not been possible without his tremendous scientific vision and a great deal of guidance. I am also in debt to Dr. Peter Dervan, Dr. Robert Grubbs, and Dr. Stephen Mayo, who serve on my thesis committee. They have provided very valuable help along the way that kept me on track in the pursuit of my degree. I have been so fortunate to have been working with a number of fantastic colleagues in Roberts’ group. Particularly, I want express my gratitude toward Shelley R. Starck, with whom I had a productive collaboration on one of my projects. Members of Roberts group, including Shuwei Li, Terry Takahashi, Ryan J. Austin, Bill Ja, Steve Millward, Christine Ueda, Adam Frankel, and Anders Olson, all have given me a great deal of help on a number of occasions in my research, and they are truly fun people to work with. I also like to thank our secretary, Margot Hoyt, for her support during my time at Caltech. I have also collaborated with people from other laboratories, e.g., Dr. Cory Hu from Prof. Varshavsky’s group, and it has been a positive experience to have a nature paper together. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

The Analects of Confucius

The analecTs of confucius An Online Teaching Translation 2015 (Version 2.21) R. Eno © 2003, 2012, 2015 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation is provided, without charge, at http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Also available as open access translations of the Four Books Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i MAPS x BOOK I 1 BOOK II 5 BOOK III 9 BOOK IV 14 BOOK V 18 BOOK VI 24 BOOK VII 30 BOOK VIII 36 BOOK IX 40 BOOK X 46 BOOK XI 52 BOOK XII 59 BOOK XIII 66 BOOK XIV 73 BOOK XV 82 BOOK XVI 89 BOOK XVII 94 BOOK XVIII 100 BOOK XIX 104 BOOK XX 109 Appendix 1: Major Disciples 112 Appendix 2: Glossary 116 Appendix 3: Analysis of Book VIII 122 Appendix 4: Manuscript Evidence 131 About the title page The title page illustration reproduces a leaf from a medieval hand copy of the Analects, dated 890 CE, recovered from an archaeological dig at Dunhuang, in the Western desert regions of China. The manuscript has been determined to be a school boy’s hand copy, complete with errors, and it reproduces not only the text (which appears in large characters), but also an early commentary (small, double-column characters). -

China's Fear of Contagion

China’s Fear of Contagion China’s Fear of M.E. Sarotte Contagion Tiananmen Square and the Power of the European Example For the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), erasing the memory of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Square massacre remains a full-time job. The party aggressively monitors and restricts media and internet commentary about the event. As Sinologist Jean-Philippe Béja has put it, during the last two decades it has not been possible “even so much as to mention the conjoined Chinese characters for 6 and 4” in web searches, so dissident postings refer instead to the imagi- nary date of May 35.1 Party censors make it “inconceivable for scholars to ac- cess Chinese archival sources” on Tiananmen, according to historian Chen Jian, and do not permit schoolchildren to study the topic; 1989 remains a “‘for- bidden zone’ in the press, scholarship, and classroom teaching.”2 The party still detains some of those who took part in the protest and does not allow oth- ers to leave the country.3 And every June 4, the CCP seeks to prevent any form of remembrance with detentions and a show of force by the pervasive Chinese security apparatus. The result, according to expert Perry Link, is that in to- M.E. Sarotte, the author of 1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe, is Professor of History and of International Relations at the University of Southern California. The author wishes to thank Harvard University’s Center for European Studies, the Humboldt Foundation, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the University of Southern California for ªnancial and institutional support; Joseph Torigian for invaluable criticism, research assistance, and Chinese translation; Qian Qichen for a conversation on PRC-U.S. -

(And Misreading) the Draft Constitution in China, 1954

Textual Anxiety Reading (and Misreading) the Draft Constitution in China, 1954 ✣ Neil J. Diamant and Feng Xiaocai In 1927, Mao Zedong famously wrote that a revolution is “not the same as inviting people to dinner” and is instead “an act of violence whereby one class overthrows the authority of another.” From the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 until Mao’s death in 1976, his revolutionary vision became woven into the fabric of everyday life, but few years were as violent as the early 1950s.1 Rushing to consolidate power after finally defeating the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) in a decades- long power struggle, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) threatened the lives and livelihood of millions. During the Land Reform Campaign (1948– 1953), landowners, “local tyrants,” and wealthier villagers were targeted for repression. In the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries in 1951, the CCP attacked former KMT activists, secret society and gang members, and various “enemy agents.”2 That same year, university faculty and secondary school teachers were forced into “thought reform” meetings, and businessmen were harshly investigated during the “Five Antis” Campaign in 1952.3 1. See Mao’s “Report of an Investigation into the Peasant Movement in Hunan,” in Stuart Schram, ed., The Political Thought of Mao Tse-tung (New York: Praeger, 1969), pp. 252–253. Although the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was extremely violent, the death toll, estimated at roughly 1.5 million, paled in comparison to that of the early 1950s. The nearest competitor is 1958–1959, during the Great Leap Forward. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

The Ideology and Significance of the Legalists School and the School Of

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 351 4th International Conference on Modern Management, Education Technology and Social Science (MMETSS 2019) The Ideology and Significance of the Legalists School and the School of Diplomacy in the Warring States Period Chen Xirui The Affiliated High School to Hangzhou Normal University [email protected] Keywords: Warring States Period; Legalists; Strategists; Modern Economic and Political Activities Abstract: In the Warring States Period, the legalist theory was popular, and the style of reforming the country was permeated in the land of China. The Seven Warring States known as Qin, Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Wei and Zhao have successively changed their laws and set the foundation for the country. The national strength hovers between the valley and school’s doctrines have accelerated the historical process of the Great Unification. The legalists laid a political foundation for the big country, constructed a power framework and formulated a complete policy. On the rule of law, the strategist further opened the gap between the powers of the country. In other words, the rule of law has created conditions for the cross-border family to seek the country and the activity of the latter has intensified the pursuit of the former. This has sparked the civilization to have a depth and breadth thinking of that period, where the need of ideology and research are crucial and necessary. This article will specifically address the background of the legalists, the background of these two generations, their historical facts and major achievements as well as the research into the practical theory that was studies during that period. -

On Confucius's Ideology of Aesthetic Order

Cultural Encounters, Conflicts, and Resolutions Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 6 12-2016 On Confucius’s Ideology of Aesthetic Order Li Wang Northeast Normal University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cecr Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Wang, Li (2016) "On Confucius’s Ideology of Aesthetic Order," Cultural Encounters, Conflicts, and Resolutions: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cecr/vol3/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Journal at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cultural Encounters, Conflicts, and Resolutions by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On Confucius’s Ideology of Aesthetic Order Abstract Advocating order, order for all things, and taking order as beauty is the core element of Confucius’s aesthetic ideology. Confucius’s thought of aesthetic order is different from others of the “hundred schools of thoughts” in the pre-Qin period, and is also diverse from the Western value of aesthetic order. Confucius’s thought of aesthetic order has its own unique value system, which has become the mainstream value of aesthetic order in the Chinese society for 2000 years until today, after being integrated with the Chinese feudal imperial system in early Han Dynasty. -

Where Was the Western Zhou Capital? a Capital City Has a Special Status in Every Country

Maria Khayutina [email protected] Where Was the Western Zhou Capital? A capital city has a special status in every country. Normally, this is a political, economical, social center. Often it is a cultural and religious center as well. This is the place of governmental headquarters and of the residence of power-holding elite and professional administrative cadres. In the societies, where transportation means are not much developed, this is at the same time the place, where producers of the top quality goods for elite consumption live and work. A country is often identified with its capital city both by its inhabitants and the foreigners. Wherefore, it is hardly possible to talk about the history of a certain state without making clear, where was located its capital. The Chinese history contains many examples, when a ruling dynasty moved its capital due to defensive or other political reasons. Often this shift caused not only geographical reorganization of the territory, but also significant changes in power relations within the state, as well as between it and its neighbors. One of the first such shifts happened in 771 BC, when the heir apparent of the murdered King You 幽 could not push back invading 犬戎 Quanrong hordes from the nowadays western 陜西 Shaanxi province, but fled to the city of 成周 Chengzhou near modern 洛陽 Luoyang, where the royal court stayed until the fall of the 周 Zhou in the late III century BC. This event is usually perceived as a benchmark between the two epochs – the “Western” and “Eastern” Zhou respectively, distinctly distinguished one from another. -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

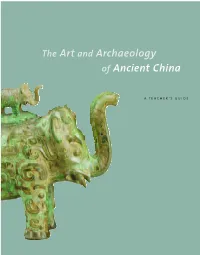

T H E a Rt a N D a Rc H a E O L O Gy O F a N C I E Nt C H I

china cover_correct2pgs 7/23/04 2:15 PM Page 1 T h e A r t a n d A rc h a e o l o g y o f A n c i e nt C h i n a A T E A C H E R ’ S G U I D E The Art and Archaeology of Ancient China A T E A C H ER’S GUI DE PROJECT DIRECTOR Carson Herrington WRITER Elizabeth Benskin PROJECT ASSISTANT Kristina Giasi EDITOR Gail Spilsbury DESIGNER Kimberly Glyder ILLUSTRATOR Ranjani Venkatesh CALLIGRAPHER John Wang TEACHER CONSULTANTS Toni Conklin, Bancroft Elementary School, Washington, D.C. Ann R. Erickson, Art Resource Teacher and Curriculum Developer, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia Krista Forsgren, Director, Windows on Asia, Atlanta, Georgia Christina Hanawalt, Art Teacher, Westfield High School, Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia The maps on pages 4, 7, 10, 12, 16, and 18 are courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The map on page 106 is courtesy of Maps.com. Special thanks go to Jan Stuart and Joseph Chang, associate curators of Chinese art at the Freer and Sackler galleries, and to Paul Jett, the museum’s head of Conservation and Scientific Research, for their advice and assistance. Thanks also go to Michael Wilpers, Performing Arts Programmer, and to Christine Lee and Larry Hyman for their suggestions and contributions. This publication was made possible by a grant from the Freeman Foundation. The CD-ROM included with this publication was created in collaboration with Fairfax County Public Schools. It was made possible, in part, with in- kind support from Kaidan Inc. -

Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary (Slmb), and Qualifying Individuals (Qi) Application

State of California—Health and Human Services Agency Department of Health Care Services QUALIFIED MEDICARE BENEFICIARY (QMB), SPECIFIED LOW-INCOME MEDICARE BENEFICIARY (SLMB), AND QUALIFYING INDIVIDUALS (QI) APPLICATION Name Social security number Medicare number Date Telephone number Date of birth Sex Marital status Married Divorced ( ) Male Female Separated Single Widowed Address (number, street) City State ZIP code This information is to help you apply for the Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB), Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary (SLMB), or the Qualifying Individual-1 (QI-1) programs. The State will pay Medicare Parts A and B premiums, deductibles, and coinsurance fees for persons eligible for the QMB program. The State will pay Medicare Part B premiums for persons eligible for SLMB or QI-1. You may apply for QMB, SLMB, or QI-1 by completing and mailing this form to your local county social services agency. To be eligible for QMB, SLMB, or QI-1, you must: Be eligible for Medicare Part A (hospital insurance). Be eligible for Medicare Part B (medical insurance). Meet the following income requirements: QMB: Net countable income at or below 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) (at or below $908* for a single person, or $1,226* for a couple). SLMB: Net countable income below 120% of the FPL (below $1,089* for a single person, or $1,471* for a couple). QI-1: Net countable income below 135% of the FPL (below $1,226* for a single person, or $1,655* for a couple). If you have a child living in the home with you, these amounts may be higher.