Visualizing Geographies of Perceived Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STEPHENS COLLEGE MISSOURI Not a Boarding Nor a Finishing School but Ati Accredited Junior College for Women

ENTERED •T THE l'OSTOFFlCE AT COLVMIIA,~MO,, ASISECONO•CLASS MATTER THE MISSOURI ALVMNVS r f .ii,: The Alumni Luncheon, June 4 Reserve a Plate Now-See Annou.uceroent, Pages 243, 244 Vot. II. No. 8 MAY, 1914 OFFICERS OF ALUM l J ASSOClA'f JONS Affiliate Wit/1 } ·our Local 01ga11ization! ST. LOUIS DENVER E. D. Smith, prrsiclent, Charles H. Talbot, president, 4127 Magnolia avenue. First National Bank Buildi ng. E. R. Evans, secretary, R. A. S mith, secretary, The Republic. 363 South Emerson street. ST. LOUIS ALUMNAE NEW YORK CITY Miss Cornelia P. Brossard, president, Finis E. t\•larshall, preside-in. 240 West Main s1ree1, l<irkwood, Mo. Hotel Marie Antoinette. Mrs. F. W. l{rietemeyer, secretory, G c. Stewart, secretary, 4937 Lansdowne avenue. 529 West Thirty-fourth street. KANSAS CITY UTAH Ed S. North, president, Leo Brandenburger, president, 1127 Scarritt Bu ilding. Care of Telluride Power Company, E. W. Patterson, secretary. Snit Lake City. 310 First National Bank Building. W. J. McMinn, secretary, KANSAS CITY ALUMNAE Temple I lotel, Snit Lake City. Mrs. James S. Summers, president. 1108 East Fortieth street. OKLAHOMA Miss Lucile Phillips, secretary, R. A. J{lein,~h midt, president, 3021 Forest avenue. 509 Pau<'rson Building, Okla horna C ity. CHICAGO Redmond S. Cole, secretary, W. T. Cross, president, Pawnee. 315 Plymouth Court. Miss Nora Edmonds, secretary, BOONE COUNTY, MISSOURI 1245 Monon Building. Marshall Gordon, p,·csidcnt, PITTSBURGH Columbia. Frank Thornton, Jr., president, J. S. Rollins, secretary, 123 North Negley avenue. Columbia. W. P. Jesse, secretary, 423 Ross avenue, Wilkinsburg, Pa. M M EN T. -

Stories of Integration, Differentiation, and Fragmentation: One University's Culture

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 428 408 CS 510 026 AUTHOR Kramer, Michael W.; Berman, Julie E. TITLE Stories of Integration, Differentiation, and Fragmentation: One University's Culture. PUB DATE 1998-11-00 NOTE 31p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association (84th, New York, NY, November 21-24, 1998). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Communication Research; Higher Education; *Organizational Climate; *Organizational Communication; *Story Telling; *Student Attitudes; Universities; Values ABSTRACT This study examined the culture of a university by analyzing its stories. Stories were collected over a period of five years at a large midwestern research university. Results suggest that a strong student subculture is frequently in conflict with the organization's dominant tradition-based culture. Stories illustrate the conflict between these two, as well as provide examples of unity between them. Other stories are ambiguous, not clearly espousing any values. In this way, the analysis suggests the importance of using all three perspectives on organizational culture defined by J. Martin (1992). The results seem applicable to studying other organizations as well, since stories of conflict and unity may provide insight into organizations' cultures. Contains 21 references and a figure illustrating the typology of organizational stories. (Author/RS) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** Culture 1 00 Running Head: Culture 00 (NI 7r- P4 Stories of Integration, Differentiation, and Fragmentation: One University's Culture By Michael W. Kramer Julie E. Berman University of Missouri--Columbia For information contact first author at: Michael W. -

Notable Property Name Property Owner

Year of HPC Notable Notable Property Name Property Owner(s) (at time of nomination) Notable Property Address Year Built Why Notable Designation One of three historic theaters on 9th Street, this one dating to the 1 Blue Note, formerly "The Varsity Theater" Richard and Patty King 17 N. Ninth St. 1930's 1998 Columbia's only "neighborhood" on the National Register of Historic 2 East Campus Neighborhood Various East Campus, Columbia Places with houses representative of those found in early 20th C 1998 Destroyed by fire in 1998, this mansion was once located on what is 3 Gordon Manor Stephens College 2100 E. Broadway 1823 now "Stephens Park." 1998 4 Jesse Hall University of Missouri MU campus 1895 Centerpiece of University of Missouri's Francis Quadrangle 1998 Former residence of J.W. "Blind" Boone, now a National Register 5 John William "Blind" Boone house City of Columbia 10 N. Fourth St. 1889 site. 1998 Historic home and property that was once the centerpiece of a 427- acre farm, now owned by the City of Columbia and operated by the 6 Maplewood House Maplewood, Nifong Boulevard and Ponderosa Drive3700 Ponderosa Drive 1877 Boone County Historical Society. 1998 As early as the 1820's but certainly by 7 Senior Hall at Stephens College Trustees of Stephens College Stephens College campus 1841 Oldest building on Stephens College campus 1998 Columbia's only remaining example of an architectural style first 8 Shotgun house Garth Avenue and Worley Streets circa 1925 associated with West Africa and the Caribbean. 1998 9 Tucker’s Jewelry Building Robert & Deborah Tucker 823-825 E. -

Alum191410.Pdf (6.985Mb)

• W©ILoIDfil N~oll O<ei o& ~no . ~ -,~ ·jl<q)ft1} . I'll Send You a Beautiful Photograph· t~~ Columns ET US double the present subscription list of The Missouri Alumnus. A doubled subscrip L tion list will enable rne to give you by far the best alumni publication.in An1erica. The proposition simply means that each present subscriber gets one new subscriber-just one, the work of a moment. For One New Cash Subscriber at $2, I'll Send You a Beautiful Photograph of The Columns. To make It Easy for You, I'll Also Send One to. Your New Subscriber. THE photograph of The Col- £ ACH new subscriber will get umns will be 8x10 inches, on The Alumnus for one full double weight, buff photographic year including this number. He paper, sepiaed, from the best neg ative I can find in Columbia. It will be enrolled a member of the will be just the same as the kind Alumni Association of the Uni you used to see in the stores here. versity of Missouri. He will get I will send one to you and one to a copy of the new Illustrated His your new subscriber in neat mail tory of the University and Cross ing tubes. You'll be proud to Reference Directory of Graduates have this picture in your home. as soon as it is issued. AIi that, You cannot afford to let this offer with a sepia column picture, makes go. You'll help the magazine and an offer on which you can get a get the picture for yourself. -

Location Ship To.Xlsx

UM ACTIVE SHIP TO CODES Sort Order: State > City > Description Updated: 19 Aug 2019 Location Eff Date Description Address 1 Address 2 AACity ST Postal Ship to Eff Date C06256 1/1/2000 399 Fremont‐Ste 2602 Dale Musser 399 Fremont St San Francisco CA 94105 1/24/2019 S008626 2/1/2000 E StL Eye Clinic‐D 2030 Optometry 601 JR Thompson Blvd East St Louis IL 62201‐1118 5/3/2019 K02456 1/1/2000 212 SW 8th Ave‐Ste B101 KCUR FM Radio 212 SW 8th Ave Topeka KS 66603 11/18/2016 C09660 1/1/1900 Hundley Whaley Farm Ag, Food & Natural Resources 1109 S Birch St Albany MO 64402 1/1/1900 C11908 1/1/2000 Ashland Therapy Cl Ste D Mizzou Therapy Svcs 101 W Broadway Ashland MO 65010 3/12/2015 C12439 1/1/2000 Redtail Prof Bldg‐Ste C MU Ashland Family Med Cl 101 Redtail Dr Ste C Ashland MO 65010 8/4/2017 C11168 1/1/2000 UM Extension‐Douglas Courthouse 203 E 2nd Ave Ava MO 65608 12/22/2011 C11147 1/1/2000 UM Extension‐Scott Scott County Extension 6458 State Hwy 77 Benton MO 63736 12/20/2011 C11012 1/2/2000 UM Extension‐Harrison Courthouse Basement 1505 Main St Bethany MO 64424‐1984 12/22/2011 C10168 2/1/2000 Heartland Financial Bldg E Jackson Cty Ext Office 1600 NE Coronado Dr Blue Springs MO 64014‐6236 7/12/2019 C11139 10/23/2015 UM Extension‐Polk Polk County Extension 110 E Jefferson Bolivar MO 65613 3/13/2018 C11399 1/1/2000 Boonville Phys Therapy Mizzou PT & Sports Med 1420 W Ashley Rd Boonville MO 65233 7/15/2016 C11102 2/1/2000 UM Extension‐Cooper Cooper Cty Ext Ste A 510 Jackson Rd Boonville MO 65233 1/10/2019 C11167 2/1/2000 Courthouse‐Basement UM Extension‐Dallas -

MU-Map-0118-Booklet.Pdf (7.205Mb)

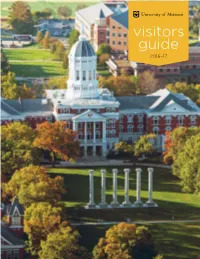

visitors guide 2016–17 EVEN WHEN THEY’RE AWAY, MAKE IT FEEL LIKE HOME WHEN YOU STAY! welcome Stoney Creek Hotel and Conference Center is the perfect place to stay when you come to visit the MU Campus. With lodge-like amenities and accommodations, you’ll experience a stay that will feel and look like home. Enjoy our beautifully designed guest rooms, complimentary to mizzou! wi-f and hot breakfast. We look forward to your stay at Stoney Creek Hotel & Conference Center! FOOD AND DRINK LOCAL STOPS table of contents 18 Touring campus works up 30 Just outside of campus, an appetite. there's still more to do and see in mid-Missouri. CAMPUS SIGHTS SHOPPING 2 Hit the highlights of Mizzou’s 24 Downtown CoMo is a great BUSINESS INDEX scenic campus. place to buy that perfect gift. 32 SPIRIT ENTERTAINMENT MIZZOU CONTACTS 12 Catch a game at Mizzou’s 27 Whether audio, visual or both, 33 Phone numbers and websites top-notch athletics facilities. Columbia’s venues are memorable. to answer all your Mizzou-related questions. CAMPUS MAP FESTIVALS Find your way around Come back and visit during 16 29 our main campus. one of Columbia’s signature festivals. The 2016–17 MU Visitors Guide is produced by Mizzou Creative for the Ofce of Visitor Relations, 104 Jesse Hall, 2601 S. Providence Rd. Columbia, MO | 573.442.6400 | StoneyCreekHotels.com Columbia, MO 65211, 800-856-2181. To view a digital version of this guide, visit missouri.edu/visitors. To advertise in next year’s edition, contact Scott Reeter, 573-882-7358, [email protected]. -

Campus Master Plan Update

MU Planning Principles Ongoing Renovation Reinforce the University Mission & Values Projects Upgrade Systems, Improve Space Use Campus Organize facilities and places to promote MU’s mission and values. Renovations at the University of Missouri are comprehensive efforts Pride of the State to address capital renewal, deferred maintenance and plan/program Express the importance of the campus to the state, nation and world. adaptation. “Campus Facilities wants the work that we do to add value to MU’s Master Plan Strong ‘Sense of Place’ education and research missions,” said Gary Ward, associate vice chan- Make the campus a distinctively meaningful and memorable place for all members of the university cellor-facilities. “By renovating existing space on campus, we are able to community and for the citizens of Missouri. replace utility infrastructure, meet current codes and make better use of An architectural studies classroom in Gwynn Hall will be renovated to outdated classrooms, research labs and other teaching spaces.” Diversity with Unity better use the existing space as well as update lighting and improve ADA Update accessibility, fire protection and fire safety systems. Create and maintain campus settings that bring together the diversity of people, heritages and culture. Renovations under way at Tate (English department) and Switzler (Commu- nications department and College of Arts & Science Special Degree UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI Recruitment-Retention Programs) replace existing mechanical, plumbing, electrical and tele- MARCH 2011 DRAFT Transmission Losses 2.4% Emphasize the qualities of the campus that help attract and keep students, faculty and staff. phone systems that have reached or exceeded their useful life (Capital Soild Waste 2.3% Renewal and Deferred Maintenance). -

Tate and Switzler Renewal Under

Sustainable campus: putting appropriate density to work Linda Eastley named MU's master planner University of Missouri he word "density" as a planning term might conjure images inda Eastley, a principal with evaluating campus space through of crowded, overpowering Sasaki, in Boston, will replace the lens of strategic priorities and T Perry Chapman as MU's program needs. buildings. Appropriate den sity for L a campus, however, can achieve a campus master planner. "It is exciting to join the University "human-scaled" balance between Eastley is eager to begin working in its commitment to achieve buildings and the pedestrian open with Mizzou administrators, faculty, carbon neutrality. The University's spaces framed by the buildings. staff and students to build u pon ongoing master planning process what Jack Robinson and Chapman allows for tangible actions to reduce The compact layout of Mizzou's have accomplished since the MU greenhouse gases, to enhance natural historic Red and White Campuses is Campus Master Plan began in 1981. resources and to prompt behavioral an example of appropriate density changes. These planning efforts, two- to four-story buildings framing a Eastley earned a bachelor's degree in landscape architecture with combined with numerous campus Tate and Switzler renewal under way series of pedestrian spaces, no space so initiatives already in motion, will large that people can't be recognized an emphasis in architecture from Boston College, and the University of Cornell University, and a master's further elevate the distinction Missouri-St. Louis. With a research n the 2009 Campus Master Plan, from across the space. -

MU-Map-0150-Front.Pdf (4.385Mb)

Welcome to ... The University of Missouri-Columbia Tomorrow, today, and yesterday are merged in •the history addition to the east was completed in 1962, to make the and development of the University of Missouri, established in Library one of the largest in the nation. Columbia in 1839, only 18 years after Missouri was admitted to The Business and Public Administration building at South statehood. Ninth Street and University Avenue, and a Fine Arts Center for The much-loved Columns-symbol of the past-stand majes- art, music, and the dramatic arts, located on Hitt Street across tically today with new space-age Research Park, where major from the Memorial Union are also in the central campus area. facilities include a IO-megawatt nuclear reactor, one of the largest university-owned in the United States. The "White" Campus The Columbia campus ( oldest and largest of the Universi- The main entrance to the east campus, more commonly ty's four campuses) is unique in having 16 divisions. known as the "white" campus, is through Memorial Tower, dedicated in 1926 as a memorial to University students who Francis Quadrangle gave their lives in World War I. The north wing of the Memorial The University of Missouri was established 132 years ago by Union honoring students who died in World War II was an act modeled after a Virginia statute, drafted and sponsored completed in 1952, and the south wing was finished in 1963. by Thomas Jefferson, which 20 years earlier had created the Adjacent to, and east of, the center tower is the non-denomina- University of Virginia. -

University of Missouri Campus

ACADEMIC UNITS 1931 when the Chinese government gave them to the School of Journalism. Today, as the story goes, if students break the silence of the archway while Accountancy, School of, 303 Cornell 882-4463 University of Missouri passing through, they will fail their next exam. Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, College of, 2-64 Agriculture, 882- 8301 6. Thomas Jefferson Statue and Tombstone: Founded in 1839, Mizzou is Campus Map Arts and Science, College of, 317 Lowry, 882-4421 the first public land-grant institution west of the Mississippi River, an outcome Business, Trulaske College of, 111 Cornell , 882-7073 of Thomas Jefferson’s dedication to expanding the United States and his Education, College of, 109 Hill, 882-0560 commitment to public education. Jefferson also is the father of the University Engineering, College of, W1025 Laferre, 882-4375 of Virginia, MU’s sister school and the model for Francis Quadrangle. Jef- Graduate School, 210 Jesse, 882-6311 ferson’s gravemarker was donated to MU by his grandchildren. In 2001, a Welcome Health Professions, School of, 504 Lewis 882-8011 statue of Thomas Jefferson, created by Colorado sculptor George Lundeen, to the University was dedicated as a gift from the trustees of the Jefferson Club. Human Environmental Sciences, College of, 117 Gwynn, 882-6424 of Missouri. As a Journalism, School of, 120 Neff, 882-4821 7. The Residence on Francis Quadrangle: Built in 1867, this house is the Columbia area 763 Law, School of, 203 Hulston, 882-6487 oldest building on campus and has been home to 18 university presidents land-grant institution Informational Science and Learning Technology, School of, 303 Townsend, and chancellors. -

MOSAICSMOSAICS University of Missouri–Columbia | College of Arts and Science | WINTER 2007 MOSAICS

MOSAICSMOSAICS university of missouri–columbia | college of arts and science | WINTER 2007 MOSAICS mosaics is published annually for alumni and friends of the College of Arts and Science at the University of Missouri–Columbia. winter 2007 Editor Nancy Moen, 317 Lowry Hall MOSAICS A BIG Milestone university of missouri–columbia | college of arts and science | WINTER 2007 Columbia, MO 65211, 573-882-2209 By Dean Michael O’Brien E-mail [email protected] As you opened this issue of Mosaics and looked for the Photographers Karen Johnson, Colin familiar face smiling back at you from Page 2, you might Suchland, Justin Kelley, Rob Hill, Nicholas Benner Blake Dinsdale features have been startled to see that Dean Richard Schwartz Art Director had morphed into somebody unrecognizable. Not to 14 Ghosts of Language Haunt Good Writing | Sacred sites The arts and sciences have worry. Dick did not undergo a nightmarish round of On the cover: inspire award-winning work. existed since Mizzou began, but the official College plastic surgery. Rather, there’s been a change in deans in of Arts and Science is 100 years old this year. 16 Surviving Cancer through Comedy | Playwright puts a Photo illustration by Blake Dinsdale the College of Arts and Science, as Dick returned to his 42 humorous spin on her own dramatic story. passions of writing fiction and teaching English. 18 American Abroad: Following a Dream | Culture clashes are I am excited to be taking over as dean of the College, even more so because 2007 Antique sports learning experiences for MU student in Dubai. -

University of Missouri Campus

ACADEMIC UNITS SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM* (35, 9) Mizzou is home to the oldest journalism school Accountancy, School of, 303 Cornell 882-4463 in the world. It was established in 1908 by Walter Williams and is always ranked among the Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, College of, 2-64 Agriculture, 882- best programs in the country. The Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute’s industry leading University of Missouri 8301 resources demonstrate new technologies advancing news production, design and delivery, information and advertising. Features include a technology and research center, the Futures Arts and Science, College of, 317 Lowry, 882-4421 Laboratory and Demonstration Center, an enlarged journalism library, administrative offices, Campus Map Business, Trulaske College of, 111 Cornell , 882-7073 fellows and graduate-studies programs and seminar space. Education, College of, 109 Hill, 882-0560 JOURNALISM ARCHWAY* (169, 10) The two stone lions that stand in the archway Engineering, College of, W1025 Laferre, 882-4375 between Neff and Walter Williams halls once guarded a Confucian temple in China. Dating from the Ming Dynasty, circa 1400, the lions became a fixture on campus in 1931 when the Chinese Graduate School, 210 Jesse, 882-6311 government gave them to the School of Journalism. Today, as the story goes, if students break Health Professions, School of, 504 Lewis 882-8011 the silence of the archway while passing through, they will fail their next exam. Welcome Human Environmental Sciences, College of, 117 Gwynn, 882-6424 MUSEUM OF ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY* (93, 11) Pickard Hall houses mid- to the University Journalism, School of, 120 Neff, 882-4821 Missouri’s largest art museum.