USM Digital Commons Currency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lykke Li Stays True to Her Style on 'Wounded Rhymes'

TODAY’s WEATHER LIFE SPORTS Review of Lykke Li’s new Sports writer David Namm album “Wounded Rhymes” reflects on last week’s loss to SEE PAGE 5 Richmond SEE PAGE 7 Mostly Sunny 79 / 54 THE VANDERBILT HUSTLER THE VOICE OF VANDERBILT SINCE 1888 MONDAY, MARCH 21, 2011 WWW .INSIDEVANDY.COM 123RD YEAR, NO. 26 CAMPUS NEWS CAMPUS NEWS University and community come Lambda together to show support for Japan kicks off LUCAS LOFFREDO weeklong Staff Writer Several hundred Vanderbilt celebration University students and Nashville community members came together in Benton Chapel KYLE BLAINE Friday for a candlelight vigil News Editor for the victims of the Japanese Tsunami. The rainbow flag will be flying The service included high this week, as the Vanderbilt speeches of support by lesbian, gay, bisexual and Vanderbilt Provost and Vice transgender community comes Chancellor for Academic Affairs together to celebrate the gains Richard McCarty, President of made by the movement this Vanderbilt Interfaith Council year. Eric Walk, and Vanderbilt Rainbow ReVU, the Vanderbilt professor James Auer from the Lambda Association’s weeklong university’s Center for U.S.- celebration of the LGBT Japan Studies and Cooperation, movement, features a variety as well as a church-wide candle of programming including lighting ceremony, a slideshow socials, awareness events, film of pictures from the relief effort screenings and lectures as a in Japan and a performance way to commemorate the year’s by the Vanderbilt Chamber efforts taken by the LGBTQI Singers. community on the university’s Vanderbilt junior Cole Garrett campus. and senior Mana Yamaguchi, Ethan Torpy, president of the who organized the event, were Vanderbilt Lambda Association, pleased with the amount of said he is excited to celebrate people that showed up. -

Lykke Li Featured in Third Episode of Wetransfer's 'Work in Progress' Series

⏲ 17 October 2018, 16:00 (CEST) Lykke Li Featured in Third Episode of WeTransfer's 'Work In Progress' Series Lykke Li opens up for the first time about the death of her mother, the birth of her child and the end of her relationship in the third episode of WeTransfer’s documentary series. October 17, 2018 - The latest episode of WeTransfer’s new series about the creative process, Work In Progress, launches today. It focuses on iconic Swedish indie-pop artist Lykke Li and can be watched on WeTransfer’s editorial platform WePresent here. In the short film (just over 6 minutes), set to Lykke Li’s latest album so sad so sexy, the acclaimed singer-songwriter gives an intimate account of her own real-life struggles in recent years. Lykke Li talks about the loss of a parent, becoming a mother and having her heart broken - and how she emerged stronger and more empowered, both mentally and creatively. Produced by Pi Studios and directed by Kaj Jefferies and Alice Lewis on 16mm film, the episode is dreamlike and melancholic at times but always underlined with a unique, raw feminine beauty. The short film acts as a candid interview and offers viewers an intimate insight into Lykke Li’s life, with personal video camera recordings of her as a child and growing up. In the footage, Lykke Li express her views on love and pain and the therapeutic nature of the creative process. This is the third episode of Work In Progress - a documentary series which celebrates the spirit of creative collaboration which defines WeTransfer's products. -

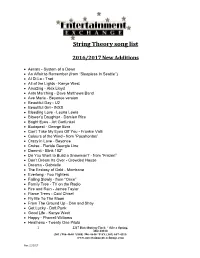

String Theory Song List

String Theory song list 2016/2017 New Additions Aerials - System of a Down An Affair to Remember (from “Sleepless In Seattle”) Al Di La - Trad All of the Lights - Kanye West Amazing - Alex Lloyd Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band Ave Maria - Beyonce version Beautiful Day - U2 Beautiful Girl - INXS Bleeding Love - Leona Lewis Blower’s Daughter - Damien Rice Bright Eyes - Art Garfunkel Budapest - George Ezra Can’t Take My Eyes Off You - Frankie Valli Colours of the Wind - from “Pocahontas” Crazy in Love - Beyonce Cruise - Florida Georgia Line Dammit - Blink 182* Do You Want to Build a Snowman? - from “Frozen” Don’t Dream Its Over - Crowded House Dreams - Gabrielle The Ecstasy of Gold - Morricone Everlong - Foo Fighters Falling Slowly - from “Once” Family Tree - TV on the Radio Fire and Rain - James Taylor Flame Trees - Cold Chisel Fly Me To The Moon From The Ground Up - Dan and Shay Get Lucky - Daft Punk Good Life - Kanye West Happy - Pharrell Williams Heathens - Twenty One Pilots 1 2217 Distribution Circle * Silver Spring, MD 20910 (301) 986-4640 *(888) 986-4640 *FAX (301) 657-4315 www.entertainmentexchange.com Rev: 11/2017 Here With Me - Dido Hey Soul Sister - Train Hey There Delilah - Plain White T’s High - Lighthouse Family Hoppipola - Sigur Ros Horse To Water - Tall Heights I Choose You - Sara Bareilles I Don’t Wanna Miss a Thing - Aerosmith I Follow Rivers - Lykke Li I Got My Mind Set On You - George Harrison I Was Made For Loving You - Tori Kelly & Ed Sheeran I Will Wait - Mumford & Sons -

Set List Select Several Songs to Be Played at Your Event / Party

FORM: SET LIST SELECT SEVERAL SONGS TO BE PLAYED AT YOUR EVENT / PARTY SONGS YOU CAN EAT AND DRINK TO MEDLEYS SONGS YOU CAN DANCE TO ELO - Mr. Blue Sky Lykke Li - I follow Rivers St. Vincent - Digital Witness Elton John - Tiny Dancer Major Lazer – Lean On Stealers Wheel - Stuck in the Middle With You Beach Boys - God Only Knows Daft Punk Medley Adele - Rolling in the Deep Empire of the Sun - Walking On a Dream Mariah Carey - Fantasy Steely Dan - Hey Nineteen Belle and Sebastian - Your Covers Blown 90's R&B Medley Amy Winehouse - Valerie Feist - 1,2,3,4 Mark Morrison - Return of the Mack Steely Dan - Peg Black Keys - Gold On the Ceiling TLC Ariel Pink - Round + Round Feist - Sea Lion Woman Mark Ronson - Uptown Funk Stevie Nicks - Stand Back Bon Iver – Holocene Usher Beach Boys - God Only Knows Fleetwood Mac - Dreams Marvin Gaye - Ain't No Mountain High Enough Stevie Wonder - Higher Ground Bon Iver - Re: Stacks Montell Jordan Beck - Debra Fleetwood Mac - Never Going Back MGMT - Electric Feel Stevie Wonder - Sir Duke Bon Iver - Skinny Love Mark Morrison Beck - Where It’s At Fleetwood Mac - Say You Love Me Michael Jackson - Human Nature Stevie Wonder- Superstition Christopher Cross - Sailing Next Belle and Sebastian - Your Covers Blown Fleetwood Mac - You Make Lovin Fun Michael Jackson - Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough Supremes - You Can't Hurry Love David Bowie - Ziggy Stardust 80's Pop + New Wave Medley Billy Preston - Nothing From Nothing Frank Ocean – Lost Michael Jackson - Human Nature Talking Heads - Burning Down the House Eagles - Hotel California New Order Black Keys - Gold On the Ceiling Frankie Vailli - December 1963 (Oh What A Night) Michael Jackson - O The Wall Talking Heads - Girlfriend is Better ELO - Mr. -

LYKKE LI RELEASES MUSIC VIDEO for “Hard Rain” from FORTHCOMING ALBUM So Sad So Sexy out JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS Watch “Hard Rain”

LYKKE LI RELEASES MUSIC VIDEO FOR “hard rain” FROM FORTHCOMING ALBUM so sad so sexy OUT JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS Watch “hard rain”: http://smarturl.it/hardrainV (New York – May 23, 2018) Los Angeles based, Swedish vocalist, producer, and songwriter Lykke Li released a seductive video over this past weekend via her story on Instagram for her single “deep end” shot entirely on an iPhone. Today, she releases part two of that love story with the cinematic video for album track “hard rain” directed by Anton Tammi. Click HERE to watch “deep end” and HERE to watch the video for “hard rain.” “hard rain” expands on the “deep end” music video, showing viewers the continuation of the wild relationship. The vertical iPhone-shot video for “deep end” was filmed during the making of the video for “hard rain,” both shot on location in Mexico City with actor Moley Talhaoui and directed by Anton Tammi. These two songs, plus the track “utopia” released by Lykke last week, mark the long-awaited coming of so sad so sexy, Lykke Li’s fourth full-length album and follow-up to 2014’s critically acclaimed I Never Learn, due June 8th via RCA Records, her first release with the label. so sad so sexy is available for pre- order now. The album’s lead single, “deep end” was produced by Jeff Bhasker, Malay, and T-Minus and album track “hard rain,” was produced by Rostam Batmanglij. This summer, Lykke will be performing at the BBC’s Biggest Weekend Festival in Belfast, All Points East in London, Chicago’s Lollapalooza and more. -

So Sad So Sexy out TODAY, JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS

LYKKE LI RELEASES FOURTH STUDIO ALBUM so sad so sexy OUT TODAY, JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS ANNOUNCES “SO SAD SO SEXY” FALL NORTH AMERICAN AND EUROPEAN TOUR WATCH LAST NIGHT’S PERFORMANCE ON LATE SHOW WITH STEPHEN COLBERT HERE COVER ART + PRESS PHOTO HERE (New York -- June 8, 2018) Today, Los Angeles based, Swedish vocalist, producer, and songwriter Lykke Li releases her critically acclaimed fourth studio album so sad so sexy via RCA Records. so sad so sexy is available now across all digital service providers: http://smarturl.it/sosadsosexy The release of the album will be celebrated with the “so sad so sexy” fall tour, presented by YOLA Mezcal, that will run throughout major cities in North America and Europe including New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, London, Paris, and more. The tour will kick off on October 5th in Washington, D.C. with general on-sale tickets becoming available in the UK on Wednesday, June 13 at 9am UK/10am CET and on Friday, June 15 at 10am local time here. In anticipation for her tour, Lykke Li has performed on several festivals outside of the US, including last month’s BBC’s Biggest Weekend Festival in Belfast, All Points East in London, and will be performing at Lollapalooza, and more. See full tour dates below or visit lykkeli.com for complete schedule. Prior to release, Lykke revealed multiple tracks including the album’s lead single “deep end,” followed by “hard rain,” “utopia,” “two nights feat Aminé,” and “sex money feelings die.” Lykke Li released two highly seductive videos, one for single “deep end” shot entirely on an iPhone, and released part two of that love story with the cinematic video for album track “hard rain” directed by Anton Tammi. -

LYKKE LI ANNOUNCES FOURTH STUDIO ALBUM So Sad So Sexy

LYKKE LI ANNOUNCES FOURTH STUDIO ALBUM so sad so sexy OUT JUNE 8TH VIA RCA RECORDS SINGLE “DEEP END” + TRACK “HARD RAIN” AVAILABLE NOW COVER ART + PRESS PHOTO HERE PHOTO CREDIT: CHLOE LE DREZEN (New York – April 19, 2018) Los Angeles based, Swedish vocalist, producer, and songwriter Lykke Li today releases new single “deep end” and additional track “hard rain.” The songs mark the long- awaited coming of so sad so sexy, Lykke Li’s fourth full-length album and follow-up to 2014’s critically acclaimed I Never Learn, due June 8th via RCA Records, her first release with the label. so sad so sexy is available for pre-order now including the album’s lead single, “deep end,” produced by Jeff Bhasker, Malay, and T-Minus and “hard rain,” produced by Rostam Batmanglij. Listen to “deep end”: http://smarturl.it/LLDeepEnd Listen to “hard rain”: http://smarturl.it/LLHardRain Since the release of her debut EP Little Bit in 2008, Lykke Li has become an iconic staple of the indie-pop world with a decade-spanning career. With three celebrated studio albums, Lykke received critical raves from “Best Album of the Year” nods from the likes of The New York Times and Rolling Stone to performing at the world’s most revered music festivals including Glastonbury and Coachella. Prior to recording this album, Lykke was busy nurturing liv, her love-child with Andrew Wyatt, Björn Yttling, Pontus Winnberg and Jeff Bhasker, which allowed this collective a mutual creative outlet. Outside of music, Lykke Li is a partner in YOLA Mezcal - a brand created in collaboration with her friends Gina Correll Aglietti (chef and stylist) and Yola Jimenez (activist and Mexican entrepreneur), who the mezcal is named after. -

The History of Rock Music - the 2000S

The History of Rock Music - The 2000s The History of Rock Music: The 2000s History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2006 Piero Scaruffi) Bards and Dreamers (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Bards of the old world order TM, ®, Copyright © 2008 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Traditionally, the purposefulness and relevance of a singer-songwriter were defined by something unique in their lyrical acumen, vocal skills and/or guitar or piano accompaniment. In the 1990s this paradigm was tested by the trend towards larger orchestrastion and towards electronic orchestration. In the 2000s it became harder and harder to give purpose and meaning to a body of work mostly relying on the message. Many singer-songwriters of the 2000s belonged to "Generation X" but sang and wrote for members of "Generation Y". Since "Generation Y" was inherently different from all the generations that had preceeded it, it was no surprise that the audience for these singer-songwriters declined. Since the members of "Generation X" were generally desperate to talk about themselves, it was not surprising that the number of such singer- songwriters increased. The net result was an odd disconnect between the musician and her or his target audience. The singer-songwriters of the 2000s generally sounded more "adult" because... they were. -

Lykke Li Discography Download Torrent Lykke Li Discography Download Torrent

lykke li discography download torrent Lykke li discography download torrent. SwatzellWertsapre: Free Muse mp3 - The 2nd Law (2012) rockbox download torrent to your pc or mobile. - Fast and reliable file torrent hosting search engine! Download free: The 2nd Law is the sixth studio album by English alternative rock band Muse, released throughout. Adobe Muse CC 2020 Crack for Mac OS Torrent Free Download. oliverwarren325: Adobe Muse CC 2020 Crack for mac is a complete development kit that allows users to develop powerful, attractive, and funky looking websites. everyone deserves music: Muse - The Resistance (2009) jedediahstevens7: everyone deserves music: Muse - The Resistance (2009).muse the resistance 2009 emotion,torrent search,zane lowe, Muse Bizzare Festival. annidevol: Muse Discography - ombined results from multile torrent sources. Super Muse-The Resistance-Real Proper (2009) Full. oiuojih: Here�s the Real Proper version of the for the new Muse album! Here�s the Real Proper version of the for the new Muse album! Undoubtedly one the most anticipated rock albums of 2009, the l. RS Muse - The Resistance (2009)@320kbps Depositfiles. habibab: Be absorbed in thought - The Guerrillas (2009)@320kbps Quote: Genre: In ruins / Mp3 sound / VBR / CBR 44,1kHz / 118 Mb 1 "Uprising" The Twilight Saga – New Moon OST - download album from torrent. muzikrand: Band Of Skulls - Friends Death Cab For Cutie - Meet Me On The Equinox Lykke Li - Possibility Anya Marina - Satellite Heart Muse - I Belong To You (New Moon Remix) Thom Yorke - Hearing Damage The Killers - A White Demon Love Song. Dvd muse paris 039 07 » Rapidshare Megaupload Free Downloads Torrent Forum File video movies clip dvd rip avi xvid rar music songs remix album mp3 movies codec player crack key serial keygen windows. -

LYKKE LI RELEASES NEW EP Still Sad Still Sexy LYKKE LI's YOLA DÍA

LYKKE LI RELEASES NEW EP still sad still sexy LISTEN HERE: https://smarturl.it/stillsadstillsexy LYKKE LI’S YOLA DÍA TO HIT L.A. ON AUGUST 18 WITH PERFORMANCES FROM LYKKE LI, CAT POWER, SOPHIE, COURTNEY LOVE & THE CHATEAU BAND, MEGAN THEE STALLION, KELSEY LU, EMPRESS OF, AND CUPCAKKE [New York, NY – July 26, 2019] Today, LA-based, Swedish vocalist, producer, and songwriter Lykke Li releases her EP still sad still sexy, a collection of new music and remixes, via RCA Records. Click HERE to listen. Lykke previously released “sex money feelings die (remix)” featuring Lil Baby and Snowsa in June and “two nights part ii” with Skrillex and Ty Dolla $ign earlier this month. The original versions of “sex money feelings die” and “two nights” are featured on Lykke’s fourth studio album so sad so sexy released last year to critical acclaim. In addition, Lykke’s inaugural YOLA DÍA festival will be held on August 18th in Los Angeles featuring an all-female lineup including performances by Lykke Li, Cat Power, SOPHIE, Courtney Love & The Chateau Band, Megan Thee Stallion, Kelsey Lu, Empress Of, and CupcakKe. YOLA DÍA will highlight extraordinary talents in music, food, and visual arts to embody the spirit and ethos of today’s female leaders and capture the voice of the future. YOLA DÍA is named after and presented by YOLA Mezcal -- a female-run mezcal brand from Oaxaca Mexico and founded by Yolanda "Yola" Jimenez. Fellow partners Lykke Li and Gina Correll Aglietti utilize a recipe and agave farm passed down by Yola’s grandfather to create their authentic and deliciously strong spirit. -

Staff Music2

FREE See LIVE Downloadable Performances Music! Staff Documentaries / Concert DVDs Pink Floyd: Pulse (1995, 2006) Music Live video of the band’s 1994 tour, featuring the complete live perfor- mance of Dark Side of the Moon . Also Picks includes a number of other classic Floyd tunes, such as “Wish You Were Here,” “Shine on You Crazy Dia- Did you know that we have music that you mond,” “Another Brick in the Wall II Pt. 2,” and “Learning to Fly.” Recommended by Jada. can check out and download to your com- puter or portable device anytime, anywhere? Afterglow Live (2004) Includes a 15-track CD and a DVD from Sarah MacLachlan’s 2003 perfor- Available Artists Include: mances in Canada. The 23-track DVD features behind-the-scenes footage, live Katy Perry • Keith Urban • J. Geils Band • Van performances, and videos. Recom- Morrison • Trace Adkins • Heart • Bill Monroe • mended by Marianne. Norah Jones • Posion • Eddie Rabbitt • Nat King Cole • Willie Nelson • Irish Tenors • Huey Hell Freezes Over (2005) Lewis & The News • Dean Martin • Thelonius Filmed during the reunion concert tour Monk • David Bowie • Johnny Cash • Doc Wat- in 1994. Includes all the hits you re- son • John Lennon • Dierks Bentley • Jethro member, and perhaps a few goodies Tull • Meat Loaf • Blue Man Group • Sammy you’ve forgotten. In addition to the live Hagar • Don MacLean • Bach, Handel, Liszt, etc. performances, there are some intriguing • Frank Sinatra • Pat Benatar • Snoop Dogg • insights into the pressures of perform- Buddy Guy • Celtic Woman • Joan Baez • The ing together after nearly 15 years. Beach Boys • Barenaked Ladies • Jimi Hendrix • Recommended by Marianne. -

CCL Sweden Online 2021 – Participant Biographies

Creative Climate Leadership Sweden 2021 - Online Participant Biographies Annika Bromberg independent Annika studied set and costume design at Dramatiska Institutet from 1994- 1997. She has designed sets and costumes for approximately 80 productions, mostly in Sweden but occasionally abroad. Annika works consistently with leading directors such as Birgitta Englin, Dritero Kasapi, Anna Takanen. Several of her productions were selected to perform at the Swedish Performing Arts Biennale. Other productions have toured internationally, for example Dritero Kasapi’s Riksteatern production HEAD ON which played Volksbühne, Berlin before moving to a venue in Istanbul. Annika has been a guest lecturer in production design at Södertörn University in Stockholm and at Göteborg University in Gothenburg. She sits on the board of the Swedish Stage Designers Guild and is involved in local politics for the Green Party in Sweden. This year, Annika is studying for a master's degree at Stockholm University of the Arts with a focus on international performing arts and sustainability. https://bromberg.se/ Caroline Lund Sverige Konstföreningar Education from UdK, Berlin and Cultural Production at Malmö University. Employed as a business developer / art educator at the Swedish Art Associations since 2012 and before that business manager / business developer at Konstfrämjandet Skåne. Lived in Berlin between 1992 and 2007 and worked there in several different cultural contexts, mainly at the theater houses Volksbuehne and Prater, at NBK, Neue Berliner Kunstverein but also as a freelance curator. Now based in Malmö. https://sverigeskonstforeningar.nu/ Cristián Petit-Laurent independent I studied Audiovisual Communication at the Iacc Institute of Santiago de Chile. Then the Master in Cinematography at Escac from Barcelona.