A Configurable Airport Reference Model for Passenger Facilitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aviation Rescue and Fire Fighting Services

Aviation Rescue and Fire Fighting Services Options for Charging ARFF – Options for Charging Contents Section 1 Purpose............................................................................. 2 Section 2 Pricing History................................................................. 2 Section 3 Delivering the Service ...................................................... 3 Section 4 International Charging Methodologies ........................... 8 Section 5 The Pricing Challenge ..................................................... 9 Section 6 Elasticity of Demand ...................................................... 10 Section 7 Assessing the Options..................................................... 12 Section 8 The Charging Options.................................................... 17 Section 9 Basis of Charging........................................................... 29 Section 10 Risk Share Arrangements............................................... 31 Section 11 Overall Revenue ............................................................. 36 Section 12 Loaction and Customer Demographics ......................... 36 Attachments Attachments……………………………………………39 Page 1 ARFF – Options for Charging 1. Purpose This “Options Paper” has been developed in order to identify a range of alternative charging methodologies; alternate revenue drivers; and alternate risk share arrangements that Airservices Australia (ASA) could apply for the provision of Aviation Rescue and Fire Fighting (ARFF) services. The paper includes: an overview -

Submission to the Joint Standing Commission on Treaties Military

Submission to the Joint Standing Commission on Treaties Military Training - Singapore EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Rockhampton Regional Council (RRC) welcomes the opportunity to make a submission to the Joint Standing Commission on Treaties into the ‘Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Singapore concerning Military Training and Training Area Development in Australia’ signed on 23 March 2020 (the Agreement). RRC recognises the close and comprehensive bilateral relationship with Singapore as one of Australia's closest and most comprehensive in Southeast Asia. Based on long-standing Commonwealth, defence, education, political, trade and tourism links, as well as on the two countries' similar strategic outlook, the relationship was elevated through the Joint declaration by the Prime Ministers of Australia and Singapore on a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (CSP), signed on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two countries. The Rockhampton Region is proud and committed to continue its integral role in the defence of the nation through the provision of goods and services in support of Australia’s defence posture and the training activities conducted at the Shoalwater Bay Training Area (SWBTA) for over 50 years. It is equally proud of its role in supporting the annual military exercises undertaken at SWBTA since 1990 by the SAF personnel which has contributed to the comprehensive and longstanding defence and security partnership between the two countries and which has been strengthened by strong patterns of joint exercises and training and close collaboration in operational environments. The unique ties and relationships that have been established between the people and business community of Rockhampton and those in Singapore have deepened over the period of this longstanding relationship, benefitting our two countries and contributing to regional economic growth. -

MINUTES AAA QLD Division

MINUTES AAA QLD Division Wednesday 21 March 2018 Brisbane Airport Conference Centre, Brisbane Chair: Rob Porter – General Manager Mackay Airport Attendees: List of Attendees Attached Apologies: Rob MacTaggart (The Airport Group) 1. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES FROM PREVIOUS MEETING: Noted minutes from last meeting. 2. WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS: Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) opened the meeting, welcomed members and thanked Smiths Detection for sponsoring the meeting. Also thanked our division dinner sponsors Trident Services and Airport Equipment. Noted the excellent presentation from Neil Scales at the dinner, noting that we will invite him back in 12 months’ time to share his experiences. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) encouraged members to provide feedback to the AAA team on the recent communications innovations (airport professional, the centre line, social media, etc.) The hot topics section at the end of the agenda was noted and the Chair, encouraged members to share their thoughts. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) encouraged members to provide feedback on the number and structure of division meetings. Noted ‘out of the box’ topic suggestions are always welcome. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) provided members with an overview of the agenda. Noting the ‘around the tarmacs’ section and encouraged members share their activity. QLD Overview Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) noted increase pressure across the state in access to aircraft, this has put upwards pressure on regional airfares in particular. 1 3. AAA UPDATE Simon Bourke (Policy Director AAA) noted key topics that the AAA had been working on over the past 6 months. Security Changes Proposed changes to Aviation Security will have an impact on all aviation sectors. -

Rockhampton City Council Inquiry Into Commercial Regional Aviation Services in Australia and Transport Links to Major Populated Islands ______

SUBMISSION TO HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORT AND REGIONAL SERVICES INQUIRY INTO COMMERCIAL REGIONAL AVIATION SERVICES IN AUSTRALIA AND TRANSPORT LINKS TO MAJOR POPULATED ISLANDS Compiled by Rockhampton Airport 3 September 2002 Inquiry into Commercial Regional Aviation Services in Australia and Transport Links to Major Populated Islands Submitted to: House of Representatives Standing Committee on Transport and Regional Services Submitted by: Rockhampton City Council Inquiry into Commercial Regional Aviation Services in Australia and Transport Links to Major Populated Islands _____________________________________________ Introduction Rockhampton City Council, as owner operator of Rockhampton Airport and in recognising its geographic location in relation to Central Queensland, has continued in its endeavours to provide air transport facilities, which are not only compatible with user’s expectations, but also capable of encouraging greater use. Recent expansion works at Rockhampton Airport have now provided this airport with the capability of facilitating all aircraft up to and including the latest wide bodied variants. If the potential of the region is to be realised for the benefit of all, Rockhampton requires the services of a stable and growing airline industry. Increased use of Rockhampton Airport, resulting from the ability of individuals and organisations to use aircraft as a means to economically access the resources and facilities offered by Central Queensland, will make a significant and ongoing contribution to Australia and the Australian economy. As a member of the Australian Airports Association, Council has received advice recommending that airports should, when making a submission, focus on the issues and their impacts relative to the local community served by the responding airport member. -

The Future of Aviation Issues Paper

The Future of Aviation Issues Paper SUBMISSION FROM AUSTRALIAN AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION CONTENTS 01 Executive Summary 02 Policy Reform 03 Federal Government Support 05 Introduction: Australia’s airports are still struggling to keep the lights on 06 Part A: COVID-19 Response - COVID Objective 1 08 COVID Objective 2: Preserving critical aviation capacity 10 COVID Objective 3: Maintaining high value freight supply lines 11 Part B: Future of Aviation - Reducing the Regulatory Burden: General Aviation 12 Reducing the Regulatory Burden: Airline access to domestic and international routes 12 Reducing the Regulatory Burden: Safe, secure and environmentally sustainable aviation 17 Reducing the Regulatory Burden & greater local decision making: Federally-leased airports 18 Targeted Assistance: Funding of regional airports 20 Targeted Assistance: Aviation skills and workforce development 21 Targeted Assistance: A sustainable and equitable funding base for CASA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Airports are critical pieces of national infrastructure keeping communities connected and linking Australia to the rest of the globe. Airports are the gateway to our nation’s world-class tourism markets, essential for global business, the facilitators of emergency support, ensure the swift delivery of essential medical supplies, trade and freight. Airports assist in bushfire fighting operations, farming activities and in many rural and regional communi- ties, they are the only public transport link to larger towns and cities. CONTENTSBefore the COVID-19 pandemic, our nation’s airport sector supported more than 200,000 jobs and contributed $35 billion – around two per cent – to Australia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). During the pandemic, airports – large and small – have been good corporate citizens, staying open to help the government bring Australians home from overseas, to move freight in and out of the country and to get essential workers such as medical professionals to where they’re needed. -

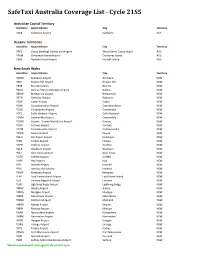

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Improving the Accuracy of Hourly Satellite-Derived Solar Irradiance by Combining with Dynamically Downscaled Estimates Using Generalised Additive Models ⇑ Robert J

Solar Energy 135 (2016) 854–863 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Solar Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/solener Improving the accuracy of hourly satellite-derived solar irradiance by combining with dynamically downscaled estimates using generalised additive models ⇑ Robert J. Davy , Jing R. Huang, Alberto Troccoli CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, GPO Box 3023, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia article info abstract Article history: The gridded hourly solar irradiance derived from satellite imagery by the Australian Bureau of Received 10 September 2015 Meteorology represents the current state of the art in quantification of the long-term solar resource Received in revised form 14 June 2016 for locations where no ground measurements are available. Using nonparametric regression, we test Accepted 20 June 2016 the potential for the satellite-derived global horizontal irradiance and direct normal irradiance to be Available online 1 July 2016 improved by combining with irradiance that has been dynamically downscaled using a numerical weather prediction (NWP) model. NWP irradiance, together with the satellite irradiance, solar zenith Keywords: angle and their interaction terms are used as inputs to generalised additive models (GAM) using smooth- Clear sky index ing splines. The spatial weighting of these empirical models according to distance is also tested. Cross val- DNI GHI idation with ground measurements indicates that RMSE can be improved by a few percent over the Insolation satellite-derived irradiance. The addition of dynamically downscaled irradiance as a GAM predictor fur- ther improves RMSE by a few percent, depending on location. When these empirical models are weighted spatially over large distances (hundreds of kilometres), the results are more equivocal. -

Regional Association V (South-West Pacific)

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION REGIONAL ASSOCIATION V (SOUTH-WEST PACIFIC) ELEVENTH SESSION NOUMEA, 18-27 MAY 1994 ABRIDGED FINAL REPORT WITH RESOLUTIONS WMO-No.811 Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization - Geneva - Switzerland 1995 © 1995, World Meteorological Organization ISBN 92-63-10811-0 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expres sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Meteorological Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. CONTENTS Page GENERAL SUMMARY OF THE WORK OF THE SESSION 1. OPENING OF THE SESSION • ........ ................... ........................................................ ..................... 1 2. ORGANIZATION OF THE SESSION ......... ................ ............... ........ ........ ................... ......... ............ 2 2.1 Consideration of the report on credentials ...... ....................... ............................................... 2 2.2 Adoption of the agenda ..................................................................... ,.... ............... ........... ...... 2 2.3 Establishnient of committees ....... ........................... ...................... ........................ ............ ..... 2 2.4 Other organizational matters .................. ...... ...................... ...... ...................... .................. ..... 2 3. REpORT -

Appendix D - Regional Airport Survey

D Appendix D - Regional Airport Survey Survey aims 1.1 As described in the submissions and evidence, many councils expressed varying degrees of difficulty in managing their airports. The committee therefore decided to conduct a survey of councils that own and operate regional airports, in order to gain an understanding of: The variation in fees charged by airports; How much it costs to operate and maintain an airport; How much income is generated from airport operations; and Which councils were struggling to operate and maintain their airports. Who was surveyed 1.2 The committee chose to survey all of the councils that had made submissions to the inquiry, and added another 30 or so councils whose passenger statistics up until 2001 appeared in Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics’ Avstats data. The number of surveys was considered representative of councils that own airports, and was also manageable given the time available. Councils surveyed included those with large populations and viable air services, through to smaller councils that have no current air services. 240 REGIONAL AVIATION AND ISLAND TRANSPORT SERVICES: MAKING ENDS MEET Survey design 1.3 A simple survey was designed and mailed to 89 councils. The survey featured 16 simple questions. A copy of the survey can be found in Appendix E. The survey was approved through the Statistical Clearing House at the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Results 1.4 The committee received 69 responses from the total of 89 surveys sent out to councils. A total of 63 surveys provided data for analysis. The committee was disappointed that 20 councils could not find the time to respond to the survey. -

Europcar Participating Locations AU4.Xlsx

Canberra Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Canberra City Novotel City, 65 Northbourne Avenue Canberra ACT Alexandria 1053 Bourke Street Waterloo NSW Artarmon 1C Clarendon Street Artarmon NSW Blacktown 231 Prospect Highway Seven Hills NSW Coffs Harbour Airport Terminal Building Airport Drive Coffs Harbour NSW Coffs Harbour City 194 Pacific Highway Corner Bailey Avenue Coffs Harbour NSW Darling Harbour 320 Harris Street Pyrmont NSW Milperra 299-301 Milperra Road Milperra NSW Newcastle Airport Terminal Building, Williamtown Drive Williamtown NSW Newcastle City 20 Denison Street West NSW Parramatta 78-84 Parramatta Road Granville NSW Penrith 6-8 Doonmore Street Penrith NSW Sydney Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building, Sydney Airport Mascot NSW Sydney Central Inside Mercure Hotel, 818-820 George Street Sydney NSW Sydney City Pullman Hotel, 36 College Street Sydney NSW Wollongong 8A Flinders Street Wollongong NSW A&G Laverton 105 William Angliss Drive Laverton North VIC Albion 2/ 590 Ballarat Road Albion VIC Avalon 81 Beach Road Avalon VIC Bayswater 244 Canterbury Road Bayswater VIC Blackburn 110 Whitehorse Road Blackburn VIC Clayton 2093-2097 Princess Highway Clayton VIC Epping 18 Yale Drive Epping VIC Knox Woods Accident Repair Centre, 34 Gilbert Park Drive Knoxfield VIC Melbourne Airport All Terminals, Terminal Building, Melbourne Airport Tullamarine VIC Melbourne City 89-91 Franklin Street Melbourne VIC Moorabbin 245-247 Wickham Road Moorabbin VIC Preston 580 High Street Preston VIC Richmond 26 Swan -

Lagardere Participating Locations 2019

Adelaide Airport Store Location Aelia Duty Free Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Icons Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Link Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport MAC Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Relay Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Tech2Go Terminal 1 Adelaide Airport Avalon Airport Store Location Relay Domestic Terminal Avalon Airport Aelia Duty Free International Terminal Avalon Airport Brisbane Airport Store Location Tech2Go Domestic Terminal Brisbane Airport Trader & Co Domestic Terminal Brisbane Airport Watermark Domestic Terminal Brisbane Airport Ballina Airport Store Location Relay Ballina Byron Gateway Airport Canberra Airport Store Location Relay Canberra Airport Cairns Airport Store Location Discover Domestic Terminal Cairns Airport MAC Domestic Terminal Cairns Airport Newslink/Hub Domestic Terminal Cairns Airport Aelia Duty Free International Terminal Cairns Airport Australian Made International Terminal Cairns Airport Discover International Terminal Cairns Airport Discover TNQ International Terminal Cairns Airport Purely Merino International Terminal Cairns Airport Relay International Terminal Cairns Airport Karratha Airport Store Location Café Karratha Airport LINK Karratha Airport Page 1 of 3 12 Shelley Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia ABN 92 108 952 085 Launceston Airport Store Location The Launceston Store Launceston Airport Melbourne Airport Store Location Newslink Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Newslink/Hub Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Tech2Go Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Watermark Terminal 1 Melbourne Airport Icons Terminal 2 Melbourne Airport -

AVIATION and AEROSPACE Industry and Investment Action Plan 2014-2018 Industry and Investment Planning Context

Sunshine Coast – The Natural Advantage: Regional Economic Development Strategy 2013 – 2033 AVIATION AND AEROSPACE INDUSTRY AND INVESTMENT ACTION PLAN 2014-2018 Industry and investment planning context The Sunshine Coast Regional Economic Development Strategy 2013-2033 provides a vision and blueprint for the new economy – a The Aviation and prosperous, high-value economy of choice for business, investment and employment, while offering an enviable lifestyle and environment. Aerospace industry The new economy for the Sunshine Coast will be built on: will play a pivotal role strong regional leadership and collaboration in building and shaping major capital investment in game changing projects that will re-shape the the new Sunshine Coast foundations of the economy growth and investment in seven high-value industries linked to the game economy into the future. changing projects, which will shape the population that is attracted to live and work in the region responsiveness of business and industry to demand from national and global markets investment in talent and skills so the region provides the workforce to respond to the demand of the high-value industries. The Sunshine Coast Regional Economic Development Strategy 2013-2033 is accompanied by an initial five-year implementation plan to 2018 to commence the transition to the new economy. The industry and investment plans produced for each of the high-value industries correspond to the five-year implementation plan and will evolve over time as key actions are initiated, reviewed and completed. Industry and investment plans will be reviewed and updated annually to ensure they remain responsive to the factors shaping the regional economy and the key influencers on those industries.