The Units of Time in Ancient and Medieval India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication the Hindu Date 24 June 2009 Edition Visakhapatnam Headline Concern Over Maternal, Infant Mortality Rate

NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Hindu Date 24 June 2009 Edition Visakhapatnam Headline Concern over maternal, infant mortality rate NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The New Indian Express Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Minister assures adequate supply of medicines NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication Dharitri Date 23 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Engagement NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication Dharitri Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Objective should be not to reduce maternal deaths, but stop it NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Samaya Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline We are not able to utilise Centre and World Bank funds: Prasanna Acharys NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Pragativadi Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline 67% maternal deaths occur in KBK region NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Anupam Bharat Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Free medicines to be given to pregnant women: Minister Ghadei NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication The Odisha Bhaskar Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Deliver Now for Women+Children campaign NEWS CLIPPING Client White Ribbon Alliance-India Publication Khabar Date 24 June 2009 Edition Bhubaneswar Headline Government hospitals not to give prescriptions for delivery cases NEWS CLIPPING Client -

Revised Syllabus for P.G. Courses in Philosophy

REVISED SYLLABUS FOR P.G. COURSES IN PHILOSOPHY COURSE NO. PHIL/P.G/1.1 Logic (Indian) 1. Nature of Indian Logic: the close relationship of logic, epistemology and metaphysics in the Indian tradition; primacy of logical reasoning in establishing one’ own system and refuting all rival systems; the concepts of ānvikṣikī and anumiti 2. Definition of Anumāna: Nyāya and Buddhist perspectives 3. Constituents of Anumāna: Nyāya and Buddhist perspectives 4. Process of Anumāna: Nyāya and Buddhist perspectives 5. Types of Anumāna: Nyāya and Buddhist perspectives 6. Nyāya: paķṣata, parāmarśa, definition of vyāpti 7. Inductive elements in Indian Logic: the concepts of vyāptigrahopāya, sāmānyalakṣaṇaprātyasatti, tarka, upādhi 8. Hetvābhāsa 9. Jňāniyapratibaddha-pratibandhakābhāva Suggestive Texts: Keśava Miśra: Tarkabhāṣā, ed. by Pandit Badarinath Shukla, Motilal Banarasidas Publishers Ltd., N. Delhi Dharmakīrti: Nyāyabindu, ed. by D. Malvania, Patna, 1971 Uddyotakara: Nyāyavārttika, ed. by M. M. Anantalal Thakur, ICPR Publication, N. Delhi Praśastapādabhāṣya, ed. By Ganganath Jha, Sapurnanda Sanskrit University, Benares Nyāyasūtra – Vātsayanabhāsya (select portions), ed. by MM Phanibhusan Tarkavagish, Rajya Pustak Parshad, WB Viśvanātha,Bhāṣāparichheda, ed. by Pandit Panchanan Shastri with commentary Muktavali- Samgraha, Sanskrita Pustak Bhandar Annambhatta,TarkasaṁgrahawithDipika, ed. by Pandit Panchanan Shastri, Sanskrita Pustak Bhandar (Bengali) Annambhatta,TarkasaṁgrahawithDipika, trans. by Prof. Gopinath Bhattacharya in English, Progressive Pub, 1976 Suggested Readings: S.S. Barlingay,A Modern Introduction to Indian Logic, National Publishing House, 1965 Gangadhar Kar,Tarkabhāsā Vol– I, 2nd ed. Jadavpur University Press, 2009 19 D.C. Guha,Navya Nyaya System of Logic, Motilal Banarsidass, 1979 Nandita Bandyopadhyay,The Concept of Logical Fallacies, Sanskrit Pustak Bhandar, 1977 B.K. Matilal,The Navya Nyaya Doctrine of Negation,Harvard University Press, 1968 B.K. -

2019 Drik Panchang Hindu Calendar

2019 Drik Panchang Hindu Calendar Hindu Calendar for San Francisco, California, United States Amanta Calendar - new month begins from Amavasya Page 1 of 25 January 2019 Margashirsha - Pausha 1940 Navami K Pratipada S Saptami S Purnima S Ashtami K SUN 30 24 6 1 13 7 20 15 27 23 रिव 07:29 16:55 07:30 17:01 07:29 17:08 07:26 Pausha Purnima 17:15 07:22 17:23 Shakambhari Purnima Bhanu Saptami Chandra Grahan *Purna Tula Dhanu 10:56 Meena 23:23 Mithuna 10:36 Tula Chitra 18:49 U Ashadha 31:07+ Revati 23:23 Punarvasu 15:53 Swati 24:59+ Dashami K Dwitiya S Ashtami S Pratipada K Navami K MON 31 25 7 2 14 8 21 16 28 24 सोम 07:30 16:56 07:30 17:02 07:29 17:09 07:26 17:16 07:21 17:24 Pongal Chandra Darshana Makara Sankranti Tula Makara Mesha Karka Tula 19:30 Swati 19:15 Shravana Ashwini 24:27+ Pushya 12:58 Vishakha 25:45+ Ekadashi K Tritiya S Navami S Dwitiya K Dashami K TUE 1 26 8 3 15 9 22 17 29 25 मंगल 07:30 16:57 07:30 17:03 07:29 17:10 07:25 17:17 07:21 17:25 Saphala Ekadashi Tula 13:54 Makara 23:46 Mesha 30:39+ Karka 10:02 Vrishchika Vishakha 20:10 Shravana 10:11 Bharani 24:43+ Ashlesha 10:02 Anuradha 27:11+ Dwadashi K Chaturthi S Dashami S Tritiya K Ekadashi K WED 2 27 9 4 16 10 23 18,19 30 26 बुध 07:30 16:57 07:30 17:04 07:28 17:11 07:25 17:18 07:20 17:26 Sakat Chauth Pradosh Vrat Pausha Putrada Ekadashi Lambodara Sankashti Chaturth Shattila Ekadashi Vrishchika Kumbha Vrishabha Simha Vrishchika 29:11+ Anuradha 21:34 Dhanishtha 13:20 Krittika 24:11+ P Phalguni 28:52+ Jyeshtha 29:11+ Trayodashi K Panchami S Ekadashi S Panchami K Dwadashi K THU -

2021 March Calendar

MARCH 2021 Phalguna - Chaitra 2077 Krishna Paksha Navami Shukla Paksha Pratipada Shukla Paksha Saptami Purnima Chhoti Holi Phalguna Phalguna Phalguna Holika ७ १४ २१ २८ Sun 7 914 1621 2228 Dahan Mula Uttara Bhadrapada Mrigashirsha Uttara Phalguni रवि Dhanu Kumbha Meena Kumbha Mithuna Meena Kanya Meena Krishna Paksha Dwitiya Krishna Paksha Dashami Shukla Paksha Dwitiya Shukla Paksha Ashtami Krishna Paksha Partipada Phalguna Phalguna Phalguna Phalguna १ ८ १५ २२ २९ MON 1 28 10 15 22 29 Uttara Phalguni Purva Ashadha Revati Ardra Hasta सोम Kanya Kumbha Dhanu Kumbha Meena Meena Mithuna Meena Kanya Meena Krishna Paksha Chaturthi Vijaya Ekadashi Shukla Paksha Tritiya Shukla Paksha Navami K Dwitiya Bhai Dooj Phalguna Phalguna Phalguna Phalguna २ ९ १६ २३ ३० TUE 2 49 1116 1823 24 30 Chitra Uttara Ashadha Ashwini Punarvasu Chitra मंगल Kanya Kumbha Makara Kumbha Mesha Meena Mithuna Meena Tula Meena Krishna Paksha Panchami Krishna Paksha Dwadashi Shukla Paksha Chaturthi Shukla Paksha Dashami Krishna Paksha Tritiya Phalguna Phalguna Phalguna Chaitra ३ १० १७ २४ ३१ WED 3 510 1217 1924 2531 3 Swati Shravana Ashwini Pushya Swati बुध Tula Kumbha Makara Kumbha Mesha Meena Karka Meena Tula Meena Krishna Paksha Shasti Mahashivratri Shukla Paksha Panchami Amalaki Ekadashi Subh Muhurat Phalguna Phalguna Phalguna ४ ११ १८ २५ Marriage: No Muhurat THU 4 6 11 18 2025 26 Vishakha Dhanishtha Bharani Ashlesha गुरू Griha Pravesh: No Tula Kumbha Makara Kumbha Mesha Meena Karka Meena Muhurat Krishna Paksha Saptami Krishna Paksha Chaturdashi Shukla Paksha Shasti Shukla Paksha -

Madhya Bharti 75 21.07.18 English

A Note on Paradoxes and Some Applications Ram Prasad At times thoughts in prints, dialogues, conversations and the likes create illusion among people. There may be one reason or the other that causes fallacies. Whenever one attempts to clear the illusion to get the logical end and is unable to, one may slip into the domain of paradoxes. A paradox seemingly may appear absurd or self contradictory that may have in fact a high sense of thought. Here a wide meaning of it including its shades is taken. There is a group of similar sensing words each of which challenges the wit of an onlooker. A paradox sometimes surfaces as and when one is in deep immersion of thought. Unprinted or oral thoughts including paradoxes can rarely survive. Some paradoxes always stay folded to gaily mock on. In deep immersion of thought W S Gilbert remarks on it in the following poetic form - How quaint the ways of paradox At common sense she gaily mocks1 The first student to expect great things of Philosophy only to suffer disillusionment was Socrates (Sokratez) -'what hopes I had formed and how grievously was I disappointed'. In the beginning of the twentieth century mathematicians and logicians rigidly argued on topics which appear possessing intuitively valid but apparently contrary statements. At times when no logical end is seen around and the topic felt hot, more on lookers would enter into these entanglements with argumentative approach. May be, but some 'wise' souls would manage to escape. Zeno's wraths - the Dichotomy, the Achilles, the Arrow and the Stadium made thinkers very uncomfortable all along. -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

The Indian Luni-Solar Calendar and the Concept of Adhik-Maas

Volume -3, Issue-3, July 2013 The Indian Luni-Solar Calendar and the giving rise to alternative periods of light and darkness. All human and animal life has evolved accordingly, Concept of Adhik-Maas (Extra-Month) keeping awake during the day-light but sleeping through the dark nights. Even plants follow a daily rhythm. Of Introduction: course some crafty beings have turned nocturnal to take The Hindu calendar is basically a lunar calendar and is advantage of the darkness, e.g., the beasts of prey, blood– based on the cycles of the Moon. In a purely lunar sucker mosquitoes, thieves and burglars, and of course calendar - like the Islamic calendar - months move astronomers. forward by about 11 days every solar year. But the Hindu calendar, which is actually luni-solar, tries to fit together The next natural clock in terms of importance is the the cycle of lunar months and the solar year in a single revolution of the Earth around the Sun. Early humans framework, by adding adhik-maas every 2-3 years. The noticed that over a certain period of time, the seasons concept of Adhik-Maas is unique to the traditional Hindu changed, following a fixed pattern. Near the tropics - for lunar calendars. For example, in 2012 calendar, there instance, over most of India - the hot summer gives way were 13 months with an Adhik-Maas falling between to rain, which in turn is followed by a cool winter. th th August 18 and September 16 . Further away from the equator, there were four distinct seasons - spring, summer, autumn, winter. -

Calendar 2020 #Spiritualsocialnetwork Contact Us @Rgyanindia FEBRUARY 2020 Magha - Phalguna 2076

JANUARY 2020 Pausa - Magha 2076 Subh Muhurat Sukla Paksha Dashami Krishna Paksha Dwitiya Krishna Paksha Dashami Republic Day Festivals, Vrats & Holidays Marriage: 15,16, 17, Pausha Magha Magha 1 English New Year ५ १२ १९ २६ 26 Sun 18, 20, 29, 30, 31 5 25 12 2 19 10 2 Guru Gobind Singh Jayanti Ashwini Pushya Vishakha Dhanishtha Nature Day रव. Griha Pravesh: 29, 30 Mesha Dhanu Karka Dhanu Tula Makara Makara Makara 3 Masik Durgashtami, Banada Vehicle Purchase: 3, Pausa Putrada Ekadashi Krishna Paksha Tritiya Shattila Ekadashi Sukla Paksha Tritiya Ashtami 8, 10, 17, 20, 27, 30, Pausha Magha Magha Magha 6 Vaikuntha Ekadashi, Paush 31 ६ १३ २० २७ MON 6 26 13 3 20 11 27 18 Putrada Ekadashi, Tailang Bharani Ashlesha Anuradha Shatabhisha Swami Jayanti सोम. Property Purchase: 10, 30, 31 Mesha Dhanu Karka Dhanu Vrishabha Makara Kumbha Makara 7 Kurma Dwadashi Namakaran: 2, 3, 5, Sukla Paksha Dwadashi K Chaturthi LOHRI Krishna Paksha Dwadashi Sukla Paksha Tritiya 8 Pradosh Vrat, Rohini Vrat 8, 12, 15, 16, 17, 19, Pausha Magha Magha Magha 10 Paush Purnima, Shakambhari 20, 27, 29, 30, 31 ७ १४ २१ २८ TUE 7 27 14 4 21 12 28 18 Purnima, Magh Snan Start Krittika Magha Jyeshtha Shatabhisha 12 National Youth Day, Swami मंगल. Mundan: 27, 31 Vrishabha Dhanu Simha Dhanu Vrishabha Makara Kumbha Makara Vivekananda Jayanti English New Year Sukla Paksha Trayodashi Makar Sankranti, Pongal Krishna Paksha Trayodashi Vasant Panchami 13 Sakat Chauth, Lambodara Pausha Magha Sankashti Chaturthi १ ८ १५ २२ २९ WED 1 21 8 28 15 5 22 13 29 14 Lohri Purva Bhadrapada Rohini Uttara Phalguni Mula Purva Bhadrapada 15 Makar Sankranti, Pongal बुध. -

The Tibetan Book of the Dead

The Tibetan Book of the Dead THE GREAT LIBERATION THROUGH HEARING IN THE BARDO BY GURU RINPOCHE ACCORDING TO KARMA LINGPA Translated with commentary by Francesca Fremantle & Chögyam Trungpa SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2010 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 1975 by Francesca Fremantle and Diana Mukpo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Library of Congress catalogues the original edition of this work as follows: Karma-glin-pa, 14th cent. The Tibetan book of the dead: the great liberation through hearing in the Bardo/by Guru Rinpoche according to Karma Lingpa: a new translation with commentary by Francesca Fremantle and Chögyam Trungpa.— Berkeley: Shambhala, 1975. XX,119p.: ill.; 24 cm.—(The Clear light series) Translation of the author’s Bar do thos grol. Bibliography: p. 111–112. / Includes index. eISBN 978-0-8348-2147-7 ISBN 978-0-87773-074-3 / ISBN 978-1-57062-747-7 ISBN 978-1-59030-059-6 1. Intermediate state—Buddhism. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies, Buddhist—Tibet. 3. Death (Buddhism). I. Fremantle, Francesca. II. Chögyam Trungpa, Trungpa Tulku, 1939–1987. III. Title. BQ4490.K3713 294.3′423 74-29615 MARC DEDICATED TO His Holiness the XVI Gyalwa Karmapa Rangjung Rigpi Dorje CONTENTS List of Illustrations Foreword, by Chögyam Trungpa, -

Comparison of Kannada Panchangas for Horoscope Matching

Horoscope Matching For Marriage By G H Visweswara, India. Introduction: he following panchangas published in Kannada were used for this T comparison. 1. Ontikoppal Panchanga (OP): published ri. G H Visweswara (born in 1950) has from Mysore & very popular in ‘old S Mysore’ area. Being published for 125 done his B.E in Electronics from Bangalore years.(2011-2012 edition) & PG Diploma in Computer Science from 2. Vyjayanthi Panchanga (VP): Published IIT, Bombay, with very good academic from South Kanara (Dakshina record. He has worked in very senior Kannada District) & popular in that positions upto that of CEO & MD in the area (Mangalore belt). Being Information Technology industry, published for 90 years.(2006-2007 particularly in R&D for the past 37 years. edition) He has learnt astrology by himself by 3. Shastrasiddha Shri Krishna Panchanga studying many of the best books & authors, (KP): Published from South Kanara including the classics. (Dakshina Kannada District) & popular in that area (2000 edition) 4. Dharmika Panchanga (DP): Published by Dharmika Panchanga Samithi with Head Office at Ramachandrapura Mutt, Shimoga Dist.(2009-10 edition) 1 5. V. Sampath Krishna Panchanga (VSKP) published from Mysore (appears to be used by many Vaishnavites (or Iyengars) in old Mysore areas)(2010-11 edition) 6. Raghavendra Mutt, Mantralaya Panchanga (RMP), a Madhwa community Mutt of great repute (2001-2002 edition) 7. Shri Krishna Panchanga, Udupi (SKU) published for 69 years. (2000-2001 edition); 8. Gadaga Sri Basaveshawara Panchanga (GBP); published By B G Sankeshwara group from Gadag, North Karnataka & used by Lingayat community;(2004-2005 edition) The above set covers most of the important ‘regions’ & ‘ethnic flavours’ within Karnataka. -

Vikram Samvat 2076-77 • 2020

Vikram Samvat 2076-77 • 2020 Shri Vikari and Shri Shaarvari Nama Phone: (219) 756-1111 • [email protected] www.bharatiyatemple-nwindiana.org Vikram Samvat 2076-77 • 2020 Shri Vikari and Shri Shaarvari Nama Phone: (219) 756-1111 • [email protected] 8605 Merrillville Road • Merrillville, IN 46410 www.bharatiyatemple-nwindiana.org VIKARI PUSHYA - MAGHA AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PUSHYA - MAGHA AYANA: UTTARASUNDAY, RITU: SHISHIRA MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY DHANUSH – MAKARASATURDAY, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI VIKARI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 PUSHYA - MAGHA SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY 4 AYANA: UTTARA, RITU: SHISHIRA SAPTAMI FULL NIGHT DHANUSH – MAKARA, MARGAZHI – THAI PAUSHA S SAPTAMI 09:30 ASHTAMI 11:56 NAVAMI 14:02 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY 1 THURSDAY 2 FRIDAY 3 SATURDAY -

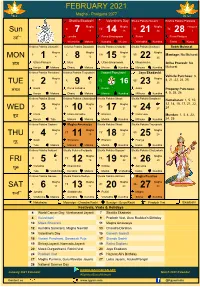

2021 February Calendar

FEBRUARY 2021 Magha - Phalguna 2077 Shattila Ekadashi Valentine's Day Shukla Paksha Navami Krishna Paksha Pratipada Magha Magha Magha Phalguna ७ १४ २१ २८ Sun 7 1114 1821 2428 1 Jyestha Purva Bhadrapada Rohini Purva Phalguni रवि Vrishchika Makara Kumbha Meena Vrishabha Kumbha Simha Kanya Krishna Paksha Chaturthi Krishna Paksha Dwadashi Shukla Paksha Chaturthi Shukla Paksha Dashami Subh Muhurat Magha Magha Magha Magha १ ८ १५ २२ Marriage: No Muhurat MON 1 48 1215 19 22 25 Uttara Phalguni Mula Uttara Bhadrapada Mrigashirsha सोम Griha Pravesh: No Kanya Makara Dhanu Makara Meena Kumbha Mithuna Kumbha Muhurat Krishna Paksha Panchami Krishna Paksha Trayodashi Vasant Panchami Jaya Ekadashi Vehicle Purchase: 3, Magha Magha २ ९ १६ २३ 4, 21, 22, 24, 25 TUE 2 59 13 16 23 26 Hasta Purva Ashadha Revati Ardra मंगल Property Purchase: Kanya Makara Dhanu Makara Meena Kumbha Mithuna Kumbha 4, 5, 25, 26 Krishna Paksha Shasti Krishna Paksha Chaturdashi Shukla Paksha Shasti Shukla Paksha Dwadashi Namakaran: 1, 5, 10, Magha Magha Magha 12, 14, 15, 17, 21, 22, ३ १० १७ २४ WED 3 610 1417 2124 27 24 Chitra Uttara Ashadha Bharani Punarvasu बुध Mundan: 1, 3, 4, 22, Kanya Tula Makara Makara Mesha Kumbha Mithuna Kumbha 24, 25 Krishna Paksha Saptami Magha Amavasya Shukla Paksha Shasti Shukla Paksha Trayodashi Magha Magha Magha Magha ४ ११ १८ २५ THU 4 711 1518 2125 28 Swati Shravana Bharani Pushya गुरू Tula Makara Makara Makara Mesha Kumbha Karka Kumbha Krishna Paksha Ashtami Shukla Paksha Pratipada Shukla Paksha Saptami Shukla Paksha Chaturdashi Magha Magha Magha ५ १२