The Golden Age of Censorship: an Analysis of Marriage and Sexuality Before and After the Implementation of the Code in 1930S Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

No Words, No Problem, P.15 Genre Legends: 8Pm, Upfront Theatre

THE GRISTLE, P.06 + ORCHARD OUTING, P.14 + BEER WEEK, P.30 c a s c a d i a REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM SKAGIT ISLAND COUNTIES 04-25-2018* • ISSUE:*17 • V.13 PIPELINE PROTESTS Protecting the Salish Sea, P.08 SKAGIT STOP Art at the schoolhouse, P.16 MARK LANEGAN A post- Celebrate AGI grunge SK T powerhouse, P.18 No words, no problem, P.15 Genre Legends: 8pm, Upfront Theatre Paula Poundstone: 8pm, Lincoln Theatre, Mount 30 A brief overview of this Vernon Backyard Brawl: 10pm, Upfront Theatre FOOD week’s happenings THISWEEK DANCE Contra Dance: 7-10:30pm, Fairhaven Library 24 MUSIC Dylan Foley, Eamon O’Leary: 7pm, Littlefield B-BOARD Celtic Center, Mount Vernon Skagit Symphony: 7:30pm, McIntyre Hall, Mount Vernon 23 WORDS FILM Book and Bake Sale: 10am-5pm, Deming Library Naomi Shihab Nye: 7pm, Performing Arts Center, Politically powered standup WWU 18 comedian Hari Kondabolu COMMUNITY MUSIC Vaisaikhi Day Celebration: 10am-5pm, Guru Nanak stops by Bellingham for an April Gursikh Gurdwaram, Lynden 16 GET OUT ART 29 gig at the Wild Buffalo Have a Heart Run: 9am, Edgewater Park, Mount Vernon 15 Everson Garden Club Sale: 9am-1pm, Everson- Goshen Rd. Native Flora Fair: 10am-3pm, Fairhaven Village STAGE Green 14 FOOD Pancake Breakfast: 8-10am, American Legion Hall, Ferndale GET OUT Pancake Breakfast: 8-10:30am, Lynden Community Center Bellingham Farmers Market: 10am-3pm, Depot 12 Market Square WORDS VISUAL Roger Small Reception: 5-7pm, Forum Arts, La WEDNESDAY [04.25.18] Conner 8 Spring has Sprung Party: 5-9pm, Matzke Fine Art MUSIC Gallery, Camano Island F.A.M.E. -

Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood

Katherine Kinney Cold Wars: Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood n 1982 Louis Gossett, Jr was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Gunnery Sergeant Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, becoming theI first African American actor to win an Oscar since Sidney Poitier. In 1989, Denzel Washington became the second to win, again in a supporting role, for Glory. It is perhaps more than coincidental that both award winning roles were soldiers. At once assimilationist and militant, the black soldier apparently escapes the Hollywood history Donald Bogle has named, “Coons, Toms, Bucks, and Mammies” or the more recent litany of cops and criminals. From the liberal consensus of WWII, to the ideological ruptures of Vietnam, and the reconstruction of the image of the military in the Reagan-Bush era, the black soldier has assumed an increasingly prominent role, ironically maintaining Hollywood’s liberal credentials and its preeminence in producing a national mythos. This largely static evolution can be traced from landmark films of WWII and post-War liberal Hollywood: Bataan (1943) and Home of the Brave (1949), through the career of actor James Edwards in the 1950’s, and to the more politically contested Vietnam War films of the 1980’s. Since WWII, the black soldier has held a crucial, but little noted, position in the battles over Hollywood representations of African American men.1 The soldier’s role is conspicuous in the way it places African American men explicitly within a nationalist and a nationaliz- ing context: U.S. history and Hollywood’s narrative of assimilation, the combat film. -

December 2016 Calendar

December Calendar Exhibits In the Karen and Ed Adler Gallery 7 Wednesday 13 Tuesday 19 Monday 27 Tuesday TIMNA TARR. Contemporary quilting. A BOB DYLAN SOUNDSWAP. An eve- HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free AFTERNOON ON BROADWAY. Guys and “THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY” (2015- December 1 through January 2. ning of clips of Nobel laureate Bob blood pressure screening conducted Dolls (1950) remains one of the great- 108 min.). Writer/director Matt Brown Dylan. 7:30 p.m. by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. est musical comedies. Frank Loesser’s adapted Robert Kanigel’s book about music and lyrics find a perfect match pioneering Indian mathematician Registrations “THE DRIFTLESS AREA” (2015-96 min.). in Damon Runyon-esque characters Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel) and Bartender Pierre (Anton Yelchin) re- and a New York City that only exists in his friendship with his mentor, Profes- In progress turns to his hometown after his parents fantasy. Professor James Kolb discusses sor G.H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons). Stephen 8 Thursday die, and finds himself in a dangerous the show and plays such unforgettable Fry co-stars as Sir Francis Spring, and Resume Workshop................December 3 situation involving mysterious Stella songs as “A Bushel and a Peck,” “Luck Be Jeremy Northam portrays Bertrand DIRECTOR’S CUT. Film expert John Bos- Entrepreneurs Workshop...December 3 (Zoe Deschanel) and violent crimi- a Lady” and “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ Russell. 7:30 p.m. co will screen and discuss Woody Al- Financial Checklist.............December 12 nal Shane (John Hawkes). Directed by the Boat.” 3 p.m. -

Styling by the Sea 140 Years of Beachwear

Styling by the Sea 140 Years of Beachwear Beach Fashions in the 1930s The stock market crash on Tuesday, October 29, 1929, and the subsequent deterioration in the value of business assets over the following three years, had a devastating impact on the economies of United States and the world at large. The high flying,care-free days of the Roaring ‘20s were over and with them went the risk taking and pushing of boundaries that characterized the lives of people during the decade. The Great Depression had begun and would continue for ten years. Spending on luxuries declined as disposable cash became scarce and people grew more fiscally conservative. Concern about employment and their long term financial prospects became paramount as the atmosphere of the country became serious and sober. Businesses closed and jobs were cut by many companies due to falling demand for their products. This caused a domino effect that resulted in economic stagnation and the deep economic depression. Luckily the pleasures derived from time spent on the beach remained an affordable and welcome means of escape from the harsh realities of everyday life. The cover of the September 3, 1932 issue of The Saturday Evening Post presented above shows a rollicking image of life at the shore at the close of summer on Labor Day Weekend. The lifeguard sits calmly on his stand, eyes closed, while pretty girls preen, an amorous swain serenades his gal who is attired in the latest “beach pajamas”, boys play leapfrog, dogs bark, babies shovel sand into pales and bathers, both large and small, hold on to a rope to save them from being knocked over by waves. -

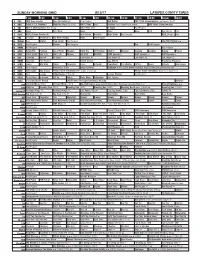

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

New Releases Watch Jul Series Highlights

SERIES HIGHLIGHTS THE DARK MUSICALS OF ERIC ROHMER’S BOB FOSSE SIX MORAL TALES From 1969-1979, the master choreographer Eric Rohmer made intellectual fi lms on the and dancer Bob Fosse directed three musical canvas of human experience. These are deeply dramas that eschewed the optimism of the felt and considered stories about the lives of Hollywood golden era musicals, fi lms that everyday people, which are captivating in their had deeply infl uenced him. With his own character’s introspection, passion, delusions, feature fi lm work, Fossae embraced a grittier mistakes and grace. His moral tales, a aesthetic, and explore the dark side of artistic collection of fi lms made over a decade between drive and the corrupting power of money the early 1960s and 1970s, elicits one of the and stardom. Fosse’s decidedly grim outlook, most essential human desires, to love and be paired with his brilliance as a director and loved. Bound in myriad other concerns, and choreographer, lent a strange beauty and ultimately, choices, the essential is never so mystery to his marvelous dark musicals. simple. Endlessly infl uential on the fi lmmakers austinfi lm.org austinfi 512.322.0145 78723 TX Austin, Street 51 1901 East This series includes SWEET CHARITY, This series includes SUZANNE’S CAREER, that followed him, Rohmer is a fi lmmaker to CABARET, and ALL THAT JAZZ. THE BAKERY GIRL OF MONCEAU, THE discover and return to over and over again. COLLECTIONEUSE, MY NIGHT AT MAUD’S, CLAIRE’S KNEE, and LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON. CINEMA SÉANCE ESSENTIAL CINEMA: Filmmakers have long recognized that cinema BETTE & JOAN is a doorway to the metaphysical, and that the Though they shared a profession and were immersive nature of the medium can bring us contemporaries, Bette Davis and Joan closer to the spiritual realm. -

Raymond Burr

Norma Shearer Biography Norma Shearer was born on August 10, 1902, in Montreal's upper-middle class Westmount area, where she studied piano, took dance lessons, and learned horseback riding as a child. This fortune was short lived, since her father lost his construction company during the post-World War I Depression, and the Shearers were forced to leave their mansion. Norma's mother, Edith, took her and her sister, Athole, to New York City, hoping to get them into acting. They stayed in an unheated boarding house, and Edith found work as a sales clerk. When the odd part did come along, it was small. Athole was discouraged, but Norma was motivated to work harder. A stream of failed auditions paid off when she landed a role in 1920's The Stealers. Arriving in Los Angeles in 1923, she was hired by Irving G. Thalberg, a boyish 24-year- old who was production supervisor at tiny Louis B. Mayer Productions. Thalberg was already renowned for his intuitive grasp of public taste. He had spotted Shearer in her modest New York appearances and urged Mayer to sign her. When Mayer merged with two other studios to become Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, both Shearer and Thalberg were catapulted into superstardom. In five years, Shearer, fueled by a larger-than-life ambition, would be a Top Ten Hollywood star, ultimately becoming the glamorous and gracious “First Lady of M-G-M.” Shearer’s private life reflected the poise and elegance of her onscreen persona. Smitten with Thalberg at their first meeting, she married him in 1927. -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

WILKINS, ARCTIC EXPLORER, VISITS NAUGATUCK PLANT Senate Over-Rode Hie Veto of Gov

WILKINS, ARCTIC EXPLORER, VISITS NAUGATUCK PLANT Senate Over-Rode Hie Veto Of Gov. Cross Patients on Pan-American Orders Roosevelts Do Hartford, Conn, April 14—(UP) L. Cross. Special Bearing Up Bravely—As —The state senate today passed a The .roll call vote was 19 to 13, Danger List Observed Here bill taking away a power held by republicans voting solidly in favoi governors for 14 years of nominat- of the measure, which the governoi Rubber Outfits ing the New Haven city court judges had declared was raised because he No Change In Condition of Appropriate Exercises Held over the veto of Governor Wilbur Is a democrat. For His Crew Mrs Innes and at Wilby High School Carl Fries According to a proclamation is- sued by President Hoover, to-day Market Unsettled As Mrs Elizabeth Innes, 70, of Thom- has been set aside as Pan-American Sir Hubert, Who Will Attempt Underwater Trip to North aston, who was painfully burned day. At the regular weekly assemb- last Saturday noon at her home, ly at Wilby high school the pupils remained on the list of Miss session room Pole in Submarine Nautilus, Pays Trip to U. S. Rub= danger today Magoon's pre- Several *Issues Had at the Waterbury hospital. Owing sented a program In keeping with ber Company’s Borough Plant Yesterday to her age the chances of her re- the day. covering are not considered very The meeting was opened with the promising. singing of “America". The program to the Democrat.) North Pole, was Some Breaks (Special recently christened Carl Fries, 52, of 596 South Main which was presented included. -

The Faded Stardom of Norma Shearer Lies Lanckman in July

CORE © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016. This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyeditMetadata, version of citation a chapter and published similar papers in at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive Lasting Screen Stars: Images that Fade and Personas that Endure. The final authenticated version is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-40733-7_6 ‘What Price Widowhood?’: The Faded Stardom of Norma Shearer Lies Lanckman In July 1934, Photoplay magazine featured an article entitled ‘The Real First Lady of Film’, introducing the piece as follows: The First Lady of the Screen – there can be only one – who is she? Her name is not Greta Garbo, or Katharine Hepburn, not Joan Crawford, Ruth Chatterton, Janet Gaynor or Ann Harding. It’s Norma Shearer (p. 28). Originally from Montréal, Canada, Norma Shearer signed her first MGM contract at age twenty. By twenty-five, she had married its most promising producer, Irving Thalberg, and by thirty-five, she had been widowed through the latter’s untimely death, ultimately retiring from the screen forever at forty. During the intervening twenty years, Shearer won one Academy Award and was nominated for five more, built up a dedicated, international fan base with an active fan club, was consistently featured in fan magazines, and starred in popular and critically acclaimed films throughout the silent, pre-Code and post-Code eras. Shearer was, at the height of her fame, an institution; unfortunately, her career is rarely as well-remembered as those of her contemporaries – including many of the stars named above.