This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King's Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tethys Festival As Royal Policy

‘The power of his commanding trident’: Tethys Festival as royal policy Anne Daye On 31 May 1610, Prince Henry sailed up the River Thames culminating in horse races and running at the ring on the from Richmond to Whitehall for his creation as Prince of banks of the Dee. Both elements were traditional and firmly Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Earl of Chester to be greeted historicised in their presentation. While the prince is unlikely by the Lord Mayor of London. A flotilla of little boats to have been present, the competitors must have been mem- escorted him, enjoying the sight of a floating pageant sent, as bers of the gentry and nobility. The creation ceremonies it were, from Neptune. Corinea, queen of Cornwall crowned themselves, including Tethys Festival, took place across with pearls and cockleshells, rode on a large whale while eight days in London. Having travelled by road to Richmond, Amphion, wreathed with seashells, father of music and the Henry made a triumphal entry into London along the Thames genius of Wales, sailed on a dolphin. To ensure their speeches for the official reception by the City of London. The cer- carried across the water in the hurly-burly of the day, ‘two emony of creation took place before the whole parliament of absolute actors’ were hired to play these tritons, namely John lords and commons, gathered in the Court of Requests, Rice and Richard Burbage1 . Following the ceremony of observed by ambassadors and foreign guests, the nobility of creation, in the masque Tethys Festival or The Queen’s England, Scotland and Ireland and the Lord Mayor of Lon- Wake, Queen Anne greeted Henry in the guise of Tethys, wife don with representatives of the guilds. -

Rediscovering the Rhetoric of Women's Intellectual

―THE ALPHABET OF SENSE‖: REDISCOVERING THE RHETORIC OF WOMEN‘S INTELLECTUAL LIBERTY by BRANDY SCHILLACE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Christopher Flint Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of ________Brandy Lain Schillace___________________________ candidate for the __English PhD_______________degree *. (signed)_____Christopher Flint_______________________ (chair of the committee) ___________Athena Vrettos_________________________ ___________William R. Siebenschuh__________________ ___________Atwood D. Gaines_______________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) ___November 12, 2009________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii Table of Contents Preface ―The Alphabet of Sense‖……………………………………...1 Chapter One Writers and ―Rhetors‖: Female Educationalists in Context…..8 Chapter Two Mechanical Habits and Female Machines: Arguing for the Autonomous Female Self…………………………………….42 Chapter Three ―Reducing the Sexes to a Level‖: Revolutionary Rhetorical Strategies and Proto-Feminist Innovations…………………..71 Chapter Four Intellectual Freedom and the Practice of Restraint: Didactic Fiction versus the Conduct Book ……………………………….…..101 Chapter Five The Inadvertent Scholar: Eliza Haywood‘s Revision -

1577-1580) Y Thomas Cavendish (1586-1588

Apropiaciones simbólicas y ejercicio de la violencia en los viajes de circunnavegación de Francis Drake (1577-1580) y Thomas Cavendish (1586-1588) [Malena López Palmero] prohistoria año XXIII, núm. 34 - dic. 2020 Prohistoria, Año XXIII, núm. 34, dic. 2020, ISSN 1851-9504 Apropiaciones simbólicas y ejercicio de la violencia en los viajes de circunnavegación de Francis Drake (1577-1580) y Thomas Cavendish (1586-1588)* Symbolic Appropriations and use of Violence in the Circumnavigation Voyages of Francis Drake (1577-1580) and Thomas Cavendish (1586-1588) MALENA LÓPEZ PALMERO Resumen Abstract A cinco siglos del primer cruce del Estrecho de Five centuries after the first crossing of the Magellan Magallanes, se analizan las experiencias inglesas de Strait, the English experiences of Francis Drake (1577- Francis Drake (1577-1580) y Thomas Cavendish (1586- 1580) and Thomas Cavendish (1586-1588) are analyzed 1588) con el propósito de reconstruir las apropiaciones with the aim of reconstructing the symbolic simbólicas que los navegantes hicieron de la región appropriations that the navigators made on the Tierra fueguina y sus habitantes. Impresos, manuscritos, del Fuego region and its inhabitants. Printed books, imágenes y mapas evocan a la alteridad americana manuscripts, images and maps evoke the más austral en tanto dispositivo de la competencia southernmost American otherness as a device of the ultramarina entre Inglaterra y España. Asimismo, dan overseas competition between England and Spain. cuenta de las hostilidades con los nativos desatadas Besides, they show the hostilities with the Natives durante el cruce, interpretadas en función de los unleashed during the crossing, which were seen objetivos de los viajeros y su validación autoral. -

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J

The Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial Sara J. Schechner (Cambridge MA) Let me tell you a tale of intrigue and ingenuity, savagery and foreign shores, sex and scientific instruments. No, it is not “Desperate Housewives,” or “CSI,” but the “Adventures of Captain John Smith, Pocahontas, and a Sundial.”1 As our story opens in 1607, we find Captain John Smith paddling upstream through the Virginia wilderness, when he is ambushed by Indians, held prisoner, and repeatedly threatened with death. His life is spared first by the intervention of his magnetic compass, whose spinning needle fascinates his captors, and then by Pocahontas, the chief’s sexy daughter. At least that is how recent movies and popular writing tell the story.2 But in fact the most famous compass in American history was more than a compass – it was a pocket sundial – and the Indian princess was no seductress, but a mere child of nine or ten years, playing her part in a shaming ritual. So let us look again at the legend, as told by John Smith himself, in order to understand what his instrument meant to him. Who was John Smith?3 When Smith (1580-1631) arrived on American shores at the age of twenty-seven, he was a seasoned adventurer who had served Lord Willoughby in Europe, had sailed the Mediterranean in a merchant vessel, and had fought for the Dutch against Spain and the Austrians against the Turks. In Transylvania, he had been captured and sold as a slave to a Turk. The Turk had sent Smith as a gift to his girlfriend in Istanbul, but Smith escaped and fled through Russia and Poland. -

Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015)

FINDLEY JR, JAMES WALTER, Ph.D. “Went to Build Castles in the Aire:” Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015). Directed by Dr. Phyllis Whitman Hunter. 266pp. This study examines the early phases of Anglo-North American colonization from 1570 to 1640 by employing the lenses of imagination and failure. I argue that English colonial projectors envisioned a North America that existed primarily in their minds – a place filled with marketable and profitable commodities waiting to be extracted. I historicize the imagined profitability of commodities like fish and sassafras, and use the extreme example of the unicorn to highlight and contextualize the unlimited potential that America held in the minds of early-modern projectors. My research on colonial failure encompasses the failure of not just physical colonies, but also the failure to pursue profitable commodities, and the failure to develop successful theories of colonization. After roughly seventy years of experience in America, Anglo projectors reevaluated their modus operandi by studying and drawing lessons from past colonial failure. Projectors learned slowly and marginally, and in some cases, did not seem to learn anything at all. However, the lack of learning the right lessons did not diminish the importance of this early phase of colonization. By exploring the variety, impracticability, and failure of plans for early settlement, this study investigates the persistent search for usefulness of America by Anglo colonial projectors in the face of high rate of -

Front Matter Template

Copyright by Reem Elghonimi 2015 The Report Committee for Reem Elghonimi Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: The Re-presentation of Arabic Optics in Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth England APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Denise Spellberg Brian Levack The Re-presentation of Arabic Optics in Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth England by Reem Elghonimi, B.S.; M.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 The Re-presentation of Arabic Optics in Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth England Reem Elghonimi, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Denise Spellberg Arabic Studies experienced a resurgence in seventeenth-century English institutions. While an awareness of the efflorescence has helped recover a fuller picture of the historical landscape, the enterprise did not foment an appreciable change in Arabic grammatical or linguistic expertise for the majority of seventeenth-century university students learning the language. As a result, the desuetude of Arabic Studies by the 1660s has been regarded as further evidence for the conclusion that the project reaped insubstantial benefits for the history of science and for the Scientific Revolution. Rather, this inquiry contends that the influence of the Arabic transmission of Greek philosophical works extended beyond Renaissance Italy to Stuart England, which not only shared a continuity with the continental reception of Latinized Arabic texts but selectively investigated some sources of original Arabic scientific ideas and methods with new rigor. -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (M-S)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 11. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/11 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1462 MACHIAVELLI, NICCOLÒ, 1469-1527 Rare 854.318 N416e 1675 The Works of the famous Nicolas Machiavel: citizen and Secretary of Florence. Written Originally in Italian, and from thence newly and faithfully Translated into English London: Printed for J.S., 1675. Description: [24], 529 [21]p. ; 32 cm. References: Wing M128. Subjects: Political science. Political ethics. War. Florence (Italy)--History. Added Author: Neville, Henry, 1620-1694, tr. Contents: -The History of florence.-The Prince.-The original of the Guelf and Ghibilin Factions.-The life of Castruccio Castracani.-The Murther of Vitelli, &c. by Duke Valentino.-The State of France.- The State of Germany.-The Marriage of Belphegor, a Novel.-Nicholas Machiavel's Letter in Vindication of Himself and His Writings. Notes: Printer's device on title-page. Title enclosed within double line rule border. Head pieces. Translated into English by Henry Neville. -

SIS Bulletin Issue 56

Scientific Instrument Society Bulletin March No. 56 1998 Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society tSSN09S6-s271 For Table of Contents, see back cover President Gerard Turner Vice.President Howard Dawes Honorary Committee Stuart Talbot, Chairman Gloria Clifton,Secretary John Didcock, Treasurer Willern Hackrnann, Editor Jane Insley,Adzwtzsmg Manager James Stratton,Meetings Secreta~. Ron Bnstow Alexander Crum-Ewing Colin Gross Arthur Middleton Liba Taub Trevor Waterman Membership and Administrative Matters The Executive Officer (Wg Cdr Geofl~,V Bennett) 31 High Street Stanford in the Vale Faringdon Tel: 01367 710223 OxOn SN7 8LH Fax: 01367 718963 e-mail: [email protected] See outside back cover for infvrmatam on membership Editorial Matters Dr. Willem D. Hackmann Museum of the History of Science Old Ashmolean Building Tel: 01865 277282 (office) Broad Street Fax: 01865 277288 Oxford OXl 3AZ Tel: 016~ 811110 (home) e-mail: willem.hac~.ox.ac.uk Society's Website http://www.sis.org.uk Advertising Jane lnsley Science Museum Tel: 0171-938 8110 South Kensington Fax: 0171-938 8118 London SW7 2DD e-mail: j.ins~i.ac.uk Organization of Meetings Mr James Stratton 101 New Bond Street Tel: 0171-629 2344 l.xmdon WIY 0AS Fax: 0171-629 8876 Typesetting and Printing Lahoflow Ltd 26-~ Wharfdale Road Tel: 0171-833 2344 King's Cross Fax: 0171-833 8150 L~mdon N! 9RY e-mail: lithoflow.co.uk Price: ~ per issue, uncluding back numbers where available. (Enquiries to the Executive Off-a:er) The Scientific Instrument Society is Registered Charity No. 326733 © The ~:~t~ L~n~.nt Society l~ Editorial l'idlil~iil,lo ~If. -

The Impact of Copernicanism on Judicial Astrology at the English Court, 1543-1660 ______

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 1-2011 'In So Many Ways Do the Planets Bear Witness': The mpI act of Copernicanism on Judicial Astrology at the English Court, 1543-1660 Justin Dohoney Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Dohoney, Justin, "'In So Many Ways Do the Planets Bear Witness': The mpI act of Copernicanism on Judicial Astrology at the English Court, 1543-1660" (2011). All Theses. 1143. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1143 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "IN SO MANY WAYS DO THE PLANETS BEAR WITNESS": THE IMPACT OF COPERNICANISM ON JUDICIAL ASTROLOGY AT THE ENGLISH COURT, 1543-1660 _____________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History _______________________________________________________ by Justin Robert Dohoney August 2011 _______________________________________________________ Accepted by: Pamela Mack, Committee Chair Alan Grubb Megan Taylor-Shockley Caroline Dunn ABSTRACT The traditional historiography of science from the late-nineteenth through the mid-twentieth centuries has broadly claimed that the Copernican revolution in astronomy irrevocably damaged the practice of judicial astrology. However, evidence to the contrary suggests that judicial astrology not only continued but actually expanded during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. During this time period, judicial astrologers accomplished this by appropriating contemporary science and mathematics. -

Maḥmūd Shāh Cholgi

From: Thomas Hockey et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, Springer Reference. New York: Springer, 2007, p. 231 Courtesy of http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_277 Cholgi: Maḥmūd Shāh Cholgi Gregg DeYoung Alternate name Khaljī: Maḥmūd Shāh Khaljī Flourished probably 15th century Since the colophon of the Persian Zīj‐i jāmiʿ mentions his name, Cholgi has traditionally been taken as the author/compiler of this collection of astronomical tables. He has been identified with the ruler of Malwah, a state in central India, from 1435 to 1469, making him, like Ulugh Beg, both prince and mathematician. Ramsey Wright has suggested, however, that the treatise was not written by the prince himself, but rather was dedicated to him by the still‐anonymous author. If the prince did indeed compose this treatise, it appears to be the only work he did in astronomy. A Persian manuscript in the Bodleian Library (Persian Manuscript Catalog, number 270) apparently chronicles the events of his reign, but no one seems to have yet examined it for any references to astronomical activity. The introduction informs us that the treatise originally comprised an introduction (muqaddima), two chapters (bāb), and a conclusion or appendix (khātima). The last chapter and appendix were already lost during the author's lifetime. The introduction has 36 sections (faṣl). The first of these sections is the best known because it was published, with facing Latin translation, by John Greaves in his Astronomica quaedam (London, 1652). This initial section contains basic geometrical definitions, an elementary introduction to Islamic hayʾa (cosmography and cosmology), and some brief explications of concepts used in spherical astronomy. -

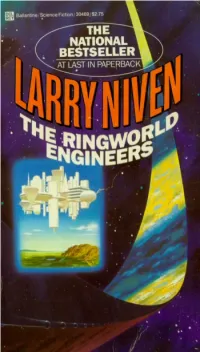

Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven PART ONE CHAPTER 1 UNDER the WIRE

Ringworld 02 Ringworld Engineers Larry Niven PART ONE CHAPTER 1 UNDER THE WIRE Louis Wu was under the wire when two men came to invade his privacy. He was in full lotus position on the lush yellow indoor-grass carpet. His smile was blissful, dreamy. The apartment was small, just one big room. He could see both doors. But, lost in the joy that only a wirehead knows, he never saw them arrive. Suddenly they were there: two pale youths, both over seven feet tall, studying Louis with contemptuous smiles. One snorted and dropped something weapon-shaped in his pocket. They were stepping forward as Louis stood up. It wasn't just the happy smile that fooled them. It was the fist-sized droud that protruded like a black plastic canker from the crown of Louis Wu's head. They were dealing with a current addict, and they knew what to expect. For years the man must have had no thought but for the wire trickling current into the pleasure center of his brain. He would be near starvation from self-neglect. He was small, a foot and a half shorter than either of the invaders. He — As they reached for him Louis bent far sideways, for balance, and kicked once, twice, thrice. One of the invaders was down, curled around himself and not breathing, before the other found the wit to back away. Louis came after him. What held the youth half paralyzed was the abstracted bliss with which Louis came to kill him. Too late, he reached for the stunner he'd pocketed. -

The Abhorred Name of Turk”: Muslims and the Politics of Identity in Seventeenth- Century English Broadside Ballads

“The Abhorred Name of Turk”: Muslims and the Politics of Identity in Seventeenth- Century English Broadside Ballads A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Katie Sue Sisneros IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Nabil Matar, adviser November 2016 Copyright 2016 by Katie Sue Sisneros Acknowledgments Dissertation writing would be an overwhelmingly isolating process without a veritable army of support (at least, I felt like I needed an army). I’d like to acknowledge a few very important people, without whom I’d probably be crying in a corner, having only typed “My Dissertation” in bold in a word document and spending the subsequent six years fiddling with margins and font size. I’ve had an amazing committee behind me: John Watkins and Katherine Scheil braved countless emails and conversations, in varying levels of panic, and offered such kind, thoughtful, and eye-opening commentary on my work that I often wonder what I ever did to deserve their time and attention. And Giancarlo Casale’s expertise in Ottoman history has proven to be equal parts inspiring and intimidating. Also, a big thank you to Julia Schleck, under whom I worked during my Masters degree, whose work was the inspiration for my entry into Anglo-Muslim studies. The bulk of my dissertation work would have been impossible (this is not an exaggeration) without access to one of the most astounding digital archives I’ve ever seen. The English Broadside Ballad Archive, maintained by the Early Modern Center in the English Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has changed markedly over the course of the eight or so years I’ve been using it, and the tireless work of its director Patricia Fumerton and the whole EBBA team has made it as comprehensive and intuitive a collection as any scholar could ask for.