Epistēmēs Metron Logos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Exciting Quote from the Text Will Lure Readers Into the Story. Quotes Must

We all know that a painter creates art with paints...a singer creates art with The story of Hansel their voice...and a musician creates and Gretel was beautiful sounds with their instrument. published by the BUasell ethti si ssp aacne ator tf ofcoursm o nt ootoh ear nimdp oitr taisn t cnreewast, esduc h asB wrointhnienrgs a G croinmtrmac ti,n w inning awards, or announcing new events. Make the story effective, accurate and co1h8e1re2n.t . BAevfooidre t hthe apt,a ssive voice. Focus on bright, by the movement of the body. It can tell original writing. Make your story fun, creative, direct and sHpaencisfice.l Uasnindg Gfarcetste, lb ahcaksg round and depth will help ayo sut oexrpyla, ine xthper ehosws aan dc wohnyc oefp at soitru atthioonu. gSahttis, fyo rth e eaxnp eicnttaetiroensst ionf gy ohuisr taourdicieanlc e, but also surprise and eevnteenrta sinh thoewm .e Umseo tthioisn s.pace to focus on other importanlti nneeawgs,e s. uIct hb aeslo wningnsin tgo aa c gonrotruacpt , owfi nEnuinrgo pawearnd s, or announcing new events. Make the story effective, accurate and coherent. Avoid the passive voice. Focus tales about children who outwit witches or on bright, original writing. Make your story fun, creative, direct and specific. Using facts, background and ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily Use this space to focus on other important newsf,a slulechn . This type of story, wPheurlel aQ famuioly’tse as winning a contract, winning awardcs,h ilodrr en are abandoned (usually in the woods) announcing new events. Make the story e"ffaeAcrteivn et,h oeuxghct ittoi nhagve qoruigointaete df rino tmhe mthedeie val accurate and coherent. -

Monsieur De Pourceaugnac, Comédie-Ballet De Molière Et Lully

Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, comédie-ballet de Molière et Lully Dossier pédagogique Une production du Théâtre de l’Eventail en collaboration avec l’ensemble La Rêveuse Mise en scène : Raphaël de Angelis Direction musicale : Florence Bolton et Benjamin Perrot Chorégraphie : Namkyung Kim Théâtre de l’Eventail 108 rue de Bourgogne, 45000 Orléans Tél. : 09 81 16 781 19 [email protected] http://theatredeleventail.com/ Sommaire Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 2 La farce dans l’œuvre de Molière ................................................................................................ 3 Molière : éléments biographiques ............................................................................................. 3 Le comique de farce .................................................................................................................... 4 Les ressorts du comique dans Monsieur de Pourceaugnac .............................................. 5 Musique baroque et comédie-ballet ........................................................................................... 7 Qui est Jean-Baptiste Lully ? ........................................................................................................ 7 La musique dans Monsieur de Pourceaugnac ..................................................................... 8 La commedia dell’arte ................................................................................................................. -

Commedia Dell'arte Au

FACULTÉ DE PHILOLOGIE Licence en Langues et Littératures Modernes (Français) L’IMPORTANCE DE LA COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE AU THÉÂTRE DE MOLIÈRE MARÍA BERRIDI PUERTAS TUTEUR : MANUEL GARCÍA MARTÍNEZ SAINT-JACQUES-DE-COMPOSTELLE, ANNéE ACADEMIQUE 2018-2019 FACULTÉ DE PHILOLOGIE Licence en Langues et Littératures Modernes (Français) L’IMPORTANCE DE LA COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE AU THÉÂTRE DE MOLIÈRE MARÍA BERRIDI PUERTAS TUTEUR : MANUEL GARCÍA MARTÍNEZ SAINT-JACQUES-DE-COMPOSTELLE, ANNÉE ACADEMIQUE 2018-2019 2 SOMMAIRE 1. Résumé…………………………………………………………………………………4 2. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..5 3. De l’introduction de la commedia dell’Arte dans la cour française……………….6 a. Qu’est-ce que c’est la commedia dell’Arte ?............................................6 i. Histoire………………………………………………...……………....6 ii. Caractéristiques essentielles…………………………………….….6 b. Les Guerres d’Italie et les premiers contacts………………………..……..8 i. Les Guerres d’Italie………………………………………………......8 ii. L’introduction de la commedia dell’Arte à la cour française……..9 4. La commedia dell’Arte dans le théâtre français………...………………………...11 a. La comédie française………………………………………………………..11 b. Molière………………………………………………………………………..12 5. La commedia dell’Arte dans la comédie de Molière……………………………...14 a. L’inspiration…………………………………………………………………..14 b. La forme et contenu…………………………………………………..……..17 c. Les masques et l’art visuel………………………………………………….19 i. La disposition scénographique…………………………………….19 ii. Le mélange de genres…………………………………………......20 iii. Les lazzi……………………………………………………………...24 iv. Les masques………………………………………………………...26 1. Personnages inspirés aux masques italiens…………….26 2. Apparitions des masques de la commedia dell’Arte.......27 3. De nouveaux masques……….……………………………27 4. Le multilinguisme……..…………………………………….29 6. Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………...32 7. Bibliographie………………………………………………………………………….34 3 IJNIVERSIOAOF DF SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTElA FACULTADE DE l ,\C.lJL'JAlJL UL I ILUI U:\1,\ rllOLOXfA 2 6 OUT. -

Dossier De Presse

Atypik Films Présente Patrick Ridremont François Berléand Virginie Efira DEAD MAN TALKING Un film belge de PATRICK RIDREMONT (Durée : 1h41) Distribution Relations Presse Atypik Films Laurence Falleur Communication 31 rue des Ombraies 57 rue du Faubourg Montmartre 92000 Nanterre 75009 Paris Eric Boquého Laurence Falleur Assisté de Sandrine Becquart Assisté de Vincent Bayol Et Jacques Domergue Tel : 01.83.92.80.51 Tel : 01.77.68.32.16. Port. : 06.48.89.41.29 Port. : 06.62.49.19.87. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Matériel de presse téléchargeable sur www.atypikfilms.com SYNOPSIS William Lamers , 40 ans, anonyme criminel condamné au Poison pour meurtre, se prépare à être exécuté. La procédure se passe dans l’indifférence générale et, ni la famille du condamné, ni celle de ses victimes n’a fait le déplacement pour assister à l’exécution. Seul le journaliste d’un minable tabloïd local est venu assister au «spectacle». Pourtant ce qui ne devait être qu’une formalité va rapidement devenir un véritable cauchemar pour Karl Raven, le directeur de la prison. Alors qu’on lui demande s’il a quelque chose à dire avant de mourir, William se met à raconter sa vie, et se lance dans un récit incroyable et bouleversant. Raven s’impatiente et appelle le Gouverneur Brodeck pour obtenir l'autorisation d'exécuter William. Mais comme la loi ne précise rien sur la longueur des dernières paroles et que le Gouverneur Stieg Brodeck, au plus bas dans les sondages, ne peut prendre aucun risque à un mois des élections, on décide de laisser William raconter son histoire jusqu’au bout. -

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017 1 Contents Art, Architecture, Music & Cinema page 3 Arabic 19 Business & Economics 19 Chinese 32 Communication, Culture, Media Studies 33 (including Journalism) Computer Science 53 Education 56 English 57 French 71 Geography 79 German 85 History 89 Italian 101 Latin 102 Law 103 Mathematics & Finance 104 Political Science 107 Psychology 120 Russian 126 Sociology & Anthropology 126 Spanish 128 Tourism 138 2 the diversity of its main players. It will thus establish Art, Architecture, the historical context of this production and to identify the protagonists, before defining the movements that Music & Cinema appear in their pulse. If the development of the course is structured around a chronological continuity, their links and how these trends overlap in reality into each IMPORTANT: ALL OUR ART COURSES ARE other will be raised and studied. TAUGHT IN FRENCH UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED COURSE CONTENT : Course Outline: AS1/1b : HISTORY OF CLASSIC CINEMA introduction Fall Semester • Impressionism • Project Genesis Lectures: 2 hours ECTS credits: 3 • "Impressionist" • The Post-Impressionism OBJECTIVE: • The néoimpressionnism To discover the great movements in the history of • The synthetism American and European cinema from 1895 to 1942. • The symbolism • Gauguin and the Nabis PontAven COURSE PROGRAM: • Modern and avantgarde The three cinematic eras: • Fauvism and Expressionism Original: • Cubism - The Lumière brothers : realistic art • Futurism - Mélies : the beginnings of illusion • Abstraction Avant-garde : - Expressionism -

Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre De L'odéon- 6E

de Molière 17 septembre 25 octobre 2008 mise en scène & scénographie Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre de l'Odéon- 6e costumes Thibault Vancraenenbroeck lumière Marion Hewlett son Xavier Jacquot collaboration artistique Anne-Françoise Benhamou collaboration à la scénographie Alexandre de Darden production Théâtre national de Strasbourg créé le 29 avril 2008 au Théâtre national de Strasbourg avec Monsieur Loyal : Jean-Pierre Bagot Cléante : Christophe Brault Tartuffe : Clément Bresson Valère : Thomas Condemine Orgon : Claude Duparfait Mariane : Julie Lesgages Elmire : Pauline Lorillard Dorine : Annie Mercier Damis : Sébastien Pouderoux Madame Pernelle : Claire Wauthion et avec la participation de l’exempt : François Loriquet Rencontre Spectacle du mardi au samedi à 20h, le dimanche à 15h, relâche le lundi Au bord de plateau jeudi 2 octobre Prix des places : 30€ - 22€ - 12€ - 7,50€ (séries 1, 2, 3, 4) à l’issue de la représentation, Tarif groupes scolaires : 11€ et 6€ (séries 2 et 3) en présence de l’équipe artistique. Entrée libre. Odéon–Théâtre de l’Europe Théâtre de l’Odéon Renseignements 01 44 85 40 90 e Place de l’Odéon Paris 6 / Métro Odéon - RER B Luxembourg L’équipe des relations avec le public : Scolaires et universitaires, associations d’étudiants Réservation et Actions pédagogiques Christophe Teillout 01 44 85 40 39 - [email protected] Emilie Dauriac 01 44 85 40 33 - [email protected] Dossier également disponible sur www.theatre-odeon.fr Certaines parties de ce dossier sont tirées du dossier pédagogique et du programme réalisés par l’équipe du Théâtre national de Strasbourg. Collaboration d’Arthur Le Stanc Tartuffe / 17 septembre › 25 octobre 2008 1 Oui, je deviens tout autre avec son entretien, Il m'enseigne à n'avoir affection pour rien ; De toutes amitiés il détache mon âme ; Et je verrais mourir frère, enfants, mère, et femme, Que je m'en soucierais autant que de cela. -

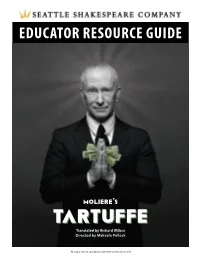

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Tartuffe is a wonderful play, and can be great for students. Its major themes of hypocrisy and gullibility provide excellent prompts for good in-class discussions. Who are the “Tartuffes” in our 21st century world? What can you do to avoid being fooled the way Orgon was? Tartuffe also has some challenges that are best to discuss with students ahead of time. Its portrayal of religion as the source of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy angered priests and the deeply religious when it was first written, which led to the play being banned for years. For his part, Molière always said that the purpose of Tartuffe was not to lampoon religion, but to show how hypocrisy comes in many forms, and people should beware of religious hypocrisy among others. There is also a challenging scene between Tartuffe and Elmire at the climax of the play (and the end of Orgon’s acceptance of Tartuffe). When Tartuffe attempts to seduce Elmire, it is up to the director as to how far he gets in his amorous attempts, and in our production he gets pretty far! This can also provide an excellent opportunity to talk with students about staunch “family values” politicians who are revealed to have had affairs, the safety of women in today’s society, and even sexual assault, depending on the age of the students. Molière’s satire still rings true today, and shows how some societal problems have not been solved, but have simply evolved into today’s context. -

Le Système Des Passions Dans La Tragédie Lullyste. L ’Exemple De La Fureur

2018 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 83–94 PHILOLOGICA 3 / ROMANISTICA PRAGENSIA LE SYSTÈME DES PASSIONS DANS LA TRAGÉDIE LULLYSTE. L ’EXEMPLE DE LA FUREUR CÉLINE BOHNERT Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne SYSTEM OF PASSIONS IN LULLY ’S TRAGEDIES EN MUSIQUE. THE EXAMPLE OF FURY Abstract: What is the dramatic action in Lully and his librettists ’ “tragédies en musique”? We argue that it consists in the necessary deployment of a set of passions carefully articulated, according to an initially euphoric conception – some passions guarantee the world ’s harmony – that grows darker as the genre finds its autonomy in relation to the spectacular con- text from which it emerged. Keywords: tragédie en musique, opera, dramaturgy, Lully, Quinault, pas- sion, action, fury, rules, necessity Mots clés : tragédie en musique, opéra, dramaturgie, Lully, Quinault, pas- sion, action, fureur, règles, nécessité Selon Pierre Perrin, l ’un des inventeurs du théâtre lyrique français, « la fin du Poète lyrique » est « d ’enlever l ’homme tout entier » en touchant « en même temps l ’oreille, l ’esprit et le cœur : l ’oreille par un beau son […], l ’esprit par un beau discours et par une belle composition de musique bien entreprise et bien raisonnée, et le cœur en excitant en lui une émotion de tendresse1 ». Sur ce pied[, précise-t-il,] j ’ai tâché de faire mon discours de musique beau, propre au chant et pathétique : et dans cette vue j ’en ai toujours choisi la matière dans les passions tendres, qui touchent le cœur par sympathie d ’une passion pareille, d ’amour ou de haine, de crainte ou de désir, de colère, de pitié, de merveille, etc., et j ’en ai banni tous les raisonnements sérieux et qui se font dans la froideur, et même les passions graves, causées par des sujets sérieux, qui touchent le cœur sans l ’attendrir2. -

Filmer Le Misanthrope À La Comédie-Française I

DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE 1 FILMER LE MISANTHROPE À LA COMÉDIE-FRANÇAISE I. MOLIÈRE À L’ÉCRAN : UNE AUTRE SCÈNE POUR LA COMÉDIE p.3 II. CLÉMENT HERVIEU-LÉGER : « LES SPECTATEURS VONT PASSER PAR LE REGARD DE DON KENT » p.6 2 III. LE DÉFI DU DIRECT : PRÉPARATION PRÉCISE ET LIBERTÉ D’IMPROVISATION p.11 IV. MOLIÈRE DANS L’ŒIL DES RÉALISATEURS p.14 DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE FILMER LE MISANTHROPE À LA COMÉDIE-FRANÇAISE I. MOLIÈRE À L’ÉCRAN : UNE AUTRE SCÈNE POUR LA COMÉDIE olière est sans doute, des auteurs français, celui dont la vie et l’œuvre ont inspiré le plus de films. Ses pièces ont fourni au cinéma un répertoire comique largement connu du grand public et ce patrimoine classique s’est vu, du cinéma des premiers temps au cinéma contemporain, perpétuellement revisité, réinventé, modernisé. Qu’elles inspirent des démarches auteuristes où le comique se teinte de noirceur, ou qu’elles fassent triompher la bouffonnerie dans les grandes comédies populaires, les pièces de Molière ont réussi à conquérir cette autre scène qu’est l’écran pour offrir au théâtre un nouvel espace où le comique puisse continuer ses métamorphoses. Italo Calvino disait des œuvres classiques qu’elles « n’avaient jamais fini de dire ce qu’elles avaient à nous dire » : la rencontre, par-delà les siècles, de Molière et de cet art résolument moderne qu’est le cinéma est encore la preuve de l’actualité toujours vivante du grand auteur classique. Molière, personnage de cinéma La vie de Molière, si romanesque dans sa trajectoire et si mystérieuse par les défauts de sa chronologie, offre au cinéma l’occasion de mêler le biographique au romanesque, tout en jouant de la mise en abyme (Molière ayant été lui-même acteur). -

Moliere Monsieur De Pourceaugnac

MOLIERE MONSIEUR DE POURCEAUGNAC « Il existe un jeu qui consiste à disposer sur quatre coins, quatre tonneaux et quatre planches bien amarrées, de monter sur ces planches, et à l’aide du corps, du souffle, de la voix, du visage et des mains, à recréer le monde…Alors il s’établit entre le spectateur et nous une circulation étroite, un échange d’âmes et de cœurs, une harmonisation du souffle de toutes les poitrines, qui nous redonnent du courage et raniment la foi que nous avons dans la vie… » J-L Barrault 1 2 Le Théâtre de l’éventail Fondée en 2006, la compagnie s’est efforcée de travailler La poésie est aussi un des axes de la compagnie. Cécile sur la tradition théâtrale, le théâtre populaire et Messineo mène ce travail à travers des lectures ou des l’itinérance. créations de spectacle, Persée et Andromède ou le plus Le premier spectacle, La Jalousie du Barbouillé et Le heureux des trois de Jules Laforgue (2011), L’homme aux Médecin volant, crée en 2007 a reçu le Prix Engagement semelles de vent sur l’oeuvre d’Arthur Rimbaud (2015). et Initiatives Jeunes dans l’Union Européenne. La seconde création, Le Médecin malgré lui (2011), a été jouée plus de 200 fois en salle ou en plein air, en France et à l’étranger (Espagne, Italie, Burkina Faso). Créé en 2014, Monsieur de Pourceaugnac, est la troisième pièce de Molière mise en scène par Raphaël de Angelis. Le spectacle sera recréé en 2016 dans sa version intégrale sous forme de « comédie-ballet » dans le cadre d’une collaboration avec l’ensemble de musique ancienne, La Rêveuse. -

Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme Molière/ Denis Podalydès

Cahier pédagogique Le Bourgeois gentilhomme Molière/ Denis Podalydès Théâtre de la place Manège de la caserne Fonck 09/11>16/11/2012 Sommaire A propos du Bourgeois gentilhomme 3 Résumé de la pièce 4 L’intrigue 5 Analyse des personnages 6 Résumé acte par acte 7 Titre et quartiers de noblesse culturelle 9 Les pratiques culturelles de Monsieur Jourdain 9 L’esthétique populaire de Monsieur Jourdain 11 Pierre Bourdieu 12 Le caractère de Monsieur Jourdain 14 Après la représentation, comme si vous y étiez… 16 Molière : le génie 17 La vie de Monsieur de Molière 19 La jeunesse de Molière 20 Les débuts difficiles 21 Les débuts de la gloire 23 Le temps des scandales 27 L’apogée de sa carrière 31 Les dernières saisons théâtrales 33 La mort de Molière 35 Les Créateurs 41 Note d’intention de Denis Podalydès 43 Note d’intention d’Eric Ruf 44 Biographies 47 Denis Podalydès, metteur en scène 47 Christophe Coin, compositeur 47 Eric Ruf, scénographie 48 Christian Lacroix, costumes 49 Infos pratiques 51 Crédits bibliographiques 52 La Presse 53 2 A propos du Bourgeois gentilhomme Dans Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, Molière tire le portrait d’un aventurier de l’esprit n’ayant d’autre désir que d’échapper à sa condition de roturier pour poser le pied sur des territoires dont il est exclu… la découverte d’une terra incognita qui, de par sa naissance, lui est interdite. Pourquoi se moquer de Monsieur Jourdain ? Le bourgeois se pique simplement de découvrir ce qu’aujourd’hui nous nommons « la culture » et il s’attelle au vaste chantier de vivre ses rêves… Et qu’importe si ces rêves sont ceux d’un homme ridicule. -

1. Ouvrages Personnels 1. Théâtre Et Musique. Dramaturgie De L'insertion

OUVRAGES 1. Ouvrages personnels 1. Théâtre et musique. Dramaturgie de l’insertion musicale dans le théâtre français (1550-1680), Paris, Champion, 2002 2. L’« Enfance de la tragédie » (1610-1642). Pratiques tragiques françaises de Hardy à Corneille, Paris, PUPS, 2014 2. Direction d’ouvrages ou de numéros de revue 1. « Racine poète » (en collaboration avec D. Moncond’huy), La Licorne, n°50, 1999 2. Les Mises en scène de la parole aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles (en collaboration avec Gilles Siouffi), Montpellier, Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2007 3. Le Spectateur de théâtre à l’âge classique (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles) (en collaboration avec Franck Salaün), Montpellier, L’Entretemps, 2008 4. Plus sur Rotrou : écrire le théâtre (en collaboration avec D. Moncond’huy), Paris, Atlande, 2008 5. « Le Théâtre de Jean Mairet », Littératures classiques, n°65, 2008 6. Les Sons du théâtre. Angleterre et France (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle). Éléments d’une histoire de l’écoute (co-direction Xavier Bisaro), Rennes, PUR, 2013 7. « Scènes de reconnaissance » (co-direction Franck Salaün et Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin), Arrêt sur scène / Scene Focus, n°2, 2013 (en ligne sur http://www.ircl.cnrs.fr) 8. « Préface et critique. Le paratexte théâtral en France, en Italie et en Espagne (XVIe-XVIIe siècles) » (co- direction Anne Cayuela, Françoise Decroisette et Marc Vuillermoz), Littératures classiques, n°83, 2014 9. « Français et langues de France dans le théâtre du XVIIe siècle », Littératures classiques, n°87, 2015 10. Les Théâtres anglais et français (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle). Contacts, circulation, influences (co-direction Florence March), Rennes, PUR, 2016 11. « Mettre en scène(s) L’École des femmes », (co-direction Jean-Noël Laurenti et Mickaël Bouffard), Arrêt sur scène / Scene Focus, n°5, 2016 12.