Minority Verdict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Opposition-Craft': an Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitte

‘Opposition-Craft’: An Evaluative Framework for Official Opposition Parties in the United Kingdom Edward Henry Lack Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds, School of Politics and International Studies May, 2020 1 Intellectual Property and Publications Statements The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2020 The University of Leeds and Edward Henry Lack The right of Edward Henry Lack to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 Acknowledgements Page I would like to thank Dr Victoria Honeyman and Dr Timothy Heppell of the School of Politics and International Studies, The University of Leeds, for their support and guidance in the production of this work. I would also like to thank my partner, Dr Ben Ramm and my parents, David and Linden Lack, for their encouragement and belief in my efforts to undertake this project. Finally, I would like to acknowledge those who took part in the research for this PhD thesis: Lord David Steel, Lord David Owen, Lord Chris Smith, Lord Andrew Adonis, Lord David Blunkett and Dame Caroline Spelman. 3 Abstract This thesis offers a distinctive and innovative framework for the study of effective official opposition politics in the United Kingdom. -

Labour Party: Jaguar Land Rover Agreement 'Great Example of Cooperation' - Ed Miliband

Oct 18, 2010 12:19 BST Labour Party: Jaguar Land Rover agreement 'great example of cooperation' - Ed Miliband Ed Miliband MP, Leader of the Labour Party, today joined John Denham MP, Labour’s Shadow Business Secretary, and Jack Dromey MP, Member of Parliament for Birmingham Erdington, to praise the cooperation between Jaguar Land Rover, the company’s workforce and the trade union, in securing long-term investment in Castle Bromwich, Solihull and Halewood. All three welcomed the deal, which is a huge boost for manufacturing in the UK while also safeguarding jobs and driving forward growth in the area. Ed Miliband MP, Leader of the Labour Party, said: “This is a great example of cooperation between Jaguar Land Rover, the company’s workforce and the trade union. As a result of this responsible negotiation, manufacturing in Castle Bromwich, Solihull and Halewood is secu re. This decision will drive growth in Britain and bring extra jobs to the West Midlands and Merseyside. “This news of £5 billion investment in British manufacturing stands in stark contrast to how the Tory-led Coalition Government are approaching the current economic situation by putting the fragile recovery at risk and undermining economic growth.” John Denham MP, Labour’s Shadow Business Secretary, said: “It is great news that Jaguar Land Rover, a truly global automotive company, has chosen Britain’s manufacturing sector as its long-term base. This news is a testament to the company’s workforce, which for generations has developed a world-class reputation for British manufacturing.” Jack Dromey MP, Member of Parliament for Erdington, the location of the Castle Bromwich site, said: “This is brilliant news in bleak times. -

All.Together

all.together the MCHFT newsletter PM Visits Leighton Also in this issue... UNICEF Accreditation Charity Update Be Involved Urgent Care Awarded Speak Out Safely Theatres and Intensive Care Choose Well This Winter #1 January 2014 welcome to all.together Welcome to the first edition of environment highly, according and our workforce take extra care All Together, our brand new to a survey which took place of themselves. Flu is common newsletter designed to keep you in the summer. The patient- at this time of year and, whilst updated with the latest news led assessments of the care it can just be unpleasant for and activities of Mid Cheshire environment took place at most us, for some it can cause Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Leighton and at Elmhurst severe health complications. If Intermediate Care Centre you are pregnant, over 65 years It’s a very exciting time to be in Winsford, with all but one old or have a long-term health part of the Trust, with important category scoring 85% or higher. condition, you should be able to projects and advancements Details on the specific categories, get vaccinated against flu for free taking place at Leighton Hospital as well as other recent from your GP. MCHFT staff are in Crewe and the Victoria achievements relating to our also able to protect themselves Infirmary in Northwich. estate, are available on page 14. and their patients by having the vaccination from Occupational Our new Operating Theatres The new facilities that are Health, with more details and Intensive Care Unit are being built will provide us available on page 12. -

Spring Business Forum Programme

Join us in March for a series of events with our Frontbench politicians including Keir Starmer, Anneliese Dodds, Ed Miliband, Bridget Phillipson, Rachel Reeves, Emily Thornberry, Chi Onwurah, Lucy Powell, Pat McFadden, Jim McMahon and many others. Monday 8 march 2021 8am – 8.50am Breakfast Anneliese Dodds ‘In Conversation with’ Helia Ebrahimi, Ch4 Economics correspondent, and audience Q and A Supported by The City of London Corporation with introductory video from Catherine McGuinness 9am - 10.30am Breakout roundtables: Three choices of topics lasting 30 minutes each Theme: Economic recovery: Building an economy for the future 1. Lucy Powell – Industrial policy after Covid 2. Bridget Phillipson, James Murray – The future of business economic support 3. Ed Miliband, Matt Pennycook – Green economic recovery 4. Pat McFadden, Abena Oppong-Asare – What kind of recovery? 5. Emily Thornberry, Bill Esterson – Boosting British business overseas 6. Kate Green, Toby Perkins – Building skills for a post Covid economy 10:30 - 11.00am Break 11.00 - 12.00pm Panel discussion An Inclusive Economic Recovery panel, with Anneliese Dodds Chair: Claire Bennison, Head of ACCA UK Anneliese Dodds, Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer Mary-Ann Stephenson, Director of the Women’s Budget Group Miatta Fahnbulleh, Chief Executive of the New Economics Foundation Rachel Bleetman, ACCA Policy and Research Manager Rain Newton-Smith, Chief Economist, CBI Supported by ACCA 14245_21 Reproduced from electronic media, promoted by David Evans, General Secretary, the Labour Party, -

Open PDF 133KB

Select Committee on Communications and Digital Corrected oral evidence: The future of journalism Tuesday 16 June 2020 3 pm Watch the meeting Members present: Lord Gilbert of Panteg (The Chair); Lord Allen of Kensington; Baroness Bull; Baroness Buscombe; Viscount Colville of Culross; Baroness Grender; Lord McInnes of Kilwinning; Baroness McIntosh of Hudnall; Baroness Meyer; Baroness Quin; Lord Storey; The Lord Bishop of Worcester. Evidence Session No. 14 Virtual Proceeding Questions 115 – 122 Witnesses I: Fraser Nelson, Editor, Spectator; and Jason Cowley, Editor, New Statesman. USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT This is a corrected transcript of evidence taken in public and webcast on www.parliamentlive.tv. 1 Examination of witnesses Fraser Nelson and Jason Cowley. Q115 The Chair: I welcome to the House of Lords Select Committee on Communications and Digital and its inquiry into the future of journalism our witnesses for the first session of evidence today, Fraser Nelson and Jason Cowley. Before I ask you to say a little more about yourselves, I should point out that today’s session will be recorded and broadcast live on parliamentlive.tv and a transcript will be produced. Thank you very much for joining us and giving us your time. I know this is Jason’s press day when he will be putting his magazine to bed. I am not sure whether it is the same for Fraser, but we are particularly grateful to you for giving up your time. Our inquiry is into the future of journalism, particularly skills, access to the industry and the impact of technology on the conduct of journalism. -

Fraser Nelson Editor, the Spectator Media Masters – September 12, 2019 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Fraser Nelson Editor, The Spectator Media Masters – September 12, 2019 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one-to-one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today I’m joined by Fraser Nelson, editor of The Spectator, the world’s oldest weekly magazine. Under his 10-year editorship it has reached a print circulation of over 70,000, the highest in its 190-year history. Previously political editor and associate editor, his roles elsewhere have included political columnist for the News of the World, political editor at the Scotsman, and business reporter with the Times. He is a board director with the Centre for Policy Studies, and the recipient of a number of awards, including the British Society of Magazine Editors’ ‘Editors’ Editor of the Year’. Fraser, thank you for joining me. Great pleasure to be here. Allie, who writes these introductions for me, clearly hates me. Editors’ Editor of the Year from the Editors’ Society. What’s that? Yes, it is, because it used to be ‘Editor of the Year’ back in the old days, and then you got this massive inflation, so now every award they give is now Editor of the Year (something or another). I see. Now that leads to a problem, so what do you call the overall award? Yes, the top one. The grand enchilada. Yes. So it’s actually a great honour. They ask other editors to vote every year. Wow. So this isn’t a panel of judges who decides the number one title, it’s other editors, and they vote for who’s going to be the ‘Editors’ Editor of the Year’, and you walk off with this lovely big trophy. -

Download Report

cover_final_02:Layout 1 20/3/14 13:26 Page 1 Internet Watch Foundation Suite 7310 First Floor Building 7300 INTERNET Cambridge Research Park Waterbeach Cambridge WATCH CB25 9TN United Kingdom FOUNDATION E: [email protected] T: +44 (0) 1223 20 30 30 ANNUAL F: +44 (0) 1223 86 12 15 & CHARITY iwf.org.uk Facebook: Internet Watch Foundation REPORT Twitter: @IWFhotline. 2013 Internet Watch Foundation Charity number: 1112 398 Company number: 3426 366 Internet Watch Limited Company number: 3257 438 Design and print sponsored by cover_final_02:Layout 1 20/3/14 13:26 Page 2 OUR VISION: TO ELIMINATE ONLINE CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE IMAGES AND VIDEOS To help us achieve this goal we work with the following operational partners: OUR MEMBERS: Our Members help us remove and disrupt the distribution of online images and videos of child sexual abuse. It is with thanks to our Members for their support that we are able to do this work. As at December 2013 we had 110 Members, largely from the online industry. These include ISPs, mobile network operators, filtering providers, search providers, content providers, and the financial sector. POLICE: In the UK we work closely with the “This has been a hugely important year for National Crime Agency CEOP child safety online and the IWF have played a Command. This partnership allows us vital role in progress made. to take action quickly against UK-hosted criminal content. We also Thanks to the efforts of the IWF and their close work with international law working with industry and the NCA, enforcement agencies to take action against child sexual abuse content hosted anywhere in the world. -

TIMPSON GE DL Card.Indd

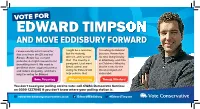

VOTE FOR EDWARD TIMPSON AND MOVE EDDISBURY FORWARD I know exactly what I voted for, I might be a remainer, I’m voting for Edward that is to leave the EU and not but the majority because I know from Europe. Britain has so much weren’t, and I accept his time living locally potential, but right now we’re not that. The country is in Eddisbury, and time benefi tting from it. We need to paralysed. I just want as Children’s Minister, get Brexit done, support business Brexit sorted, and that he cares for the and reduce inequality, and that’s voting for Edward will disadvantaged and why I’m voting for Edward. help achieve that. vulnerable. Sam, Tarporley Malcolm, Huxley Tracey, Winsford You don’t need your polling card to vote: call CWAC Democratic Services on 0300 1237045 if you don't know where your polling station is. [email protected] Edward4Eddisbury @EdwardTimpson th December, is Polling Day. TODAY, Thursday 12 Make sure you use your vote! VOTE EDWARD TIMPSON GET BREXIT DONE TIMPSON, Edward MOVE EDDISBURY FORWARD Extra funding for the NHS, with 50 million more GP surgery appointments a year, and protected increases in the state pension through the triple lock. We will not raise the rate of income tax, VAT or National Insurance, and will Polling promote our high streets with a rate cut. Better broadband, buses and mobile phone signal for rural Cheshire, and Stations support for our farmers. are open from More police for Cheshire and tougher sentencing for criminals. 7am to 10pm Millions more invested every week in science, schools, apprenticeships and Promoted by Christopher Green on behalf of Edward Timpson, both of 4 infrastructure while controlling debt. -

C/R/D Summary Skeleton Document

Application No: 14/0128N Location: Land to the north of Main Road, Wybunbury Proposal: Outline planning application with all matters reserved (apart from access) for up to 40 dwellings, incidental open space, landscaping and associated ancillary works. Applicant: The Church Commissioners for England Expiry Date: 10-Mar-2015 SUMMARY The proposed development would be contrary to Policy NE.2 and RES.5 and the development would result in a loss of open countryside. In this case Cheshire East cannot demonstrate a 5 year supply of deliverable housing sites. However, as Wybunbury Moss is identified as a Special Area of Conservation and a Ramsar Site the NPPF states that Wybunbury Moss should be given the same protection as a European site and an assessment under the Habitats Directives is required. As a result the presumption in favour of sustainable development (paragraph 14 of the NPPF) does not apply to this application. In this case specific policies in this Framework indicate development should be restricted on this site and as such the application is recommended for refusal due to its impact upon Wybunbury Moss. RECOMMENDATION REFUSE REASON FOR REFERRAL This application is referred to Strategic Planning Board as it includes an Environmental Statement. The application is also subject to a call in request from Cllr Clowes which requests that the application is referred to Committee for the following reasons: ‘This application has been brought to my attention by Wybunbury Parish Council and Hough and Chorlton Parish Council, together with the adjacent neighbours and the Wybunbury Moss Voluntary Warden. All parties object to this application on the following material grounds:- 1. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

39 Mcnally Radice Friends and Rivals Review

REVIEWS the result is a refreshing mix Dr Tim Benson is Director of the that makes fascinating reading Political Cartoon Society, an organi- for anyone interested in cur- sation for those interested in history rent affairs, one which will also and politics through the medium of be appreciated by students of cartoons. politics, history, journalism and Visit www.politicalcartoon.co.uk cartoon art. When personal ambitions collide, mutual co-operation is precluded Giles Radice: Friends and Rivals: Crosland, Jenkins and Healey (Little, Brown & Co., 2002), 382 pp. Reviewed by Tom McNally et us start with the con- narrative parallels Dangerfield’s clusion. Giles Radice has The Strange Death of Liberal Eng- Lwritten an important land in seeking to explain how book, a very readable book and both a political establishment and one that entirely justifies the a political philosophy lost its way. many favourable reviews it has I watched this story unfold received since its publication in first of all as a Labour Party re- September 2002. By the device searcher in the mid- and late them. In that respect Tony Blair of interweaving the careers and sixties, then as International Sec- and Gordon Brown did learn the ambitions of Anthony Crosland, retary of the Labour Party from lessons of history by cementing Roy Jenkins and Denis Healey, 1969–74 (the youngest since their own non-aggression pact, Radice is able to tell the tale of Denis Healey, who served in the and reaped their full reward for the rise and fall of social democ- post from 1945–52), followed by so doing. -

New Labour, Globalization, and the Competition State" by Philip G

Centerfor European Studies Working Paper Series #70 New Labour, Globalization, and the Competition State" by Philip G. Cemy** Mark Evans" Department of Politics Department of Politics University of Leeds University of York Leeds LS2 9JT, UK York YOlO SDD, U.K Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] • Will also be published in Econonry andSocitD' - We would like to thank the Nuffield Foundation, the Center for European Studies, Harvard University,and the Max-Planck-Institut fur Gesellschaftsforshung, Cologne, for their support during the writing of this paper. Abstract The concept of the Competition State differs from the "Post-Fordist State" of Regulation Theory, which asserts that the contemporary restructuring of the state is aimed at maintaining its generic function of stabilizing the national polity and promoting the domestic economy in the public interest In contrast, the Competition State focuses on disempowering the state from within with regard to a range of key tasks, roles, and activities, in the face of processes of globalization . The state does not merely adapt to exogenous structural constraints; in addition, domestic political actors take a proactive and preemptive lead in this process through both policy entrepreneurship and the rearticulation of domestic political and social coalitions, on both right and left, as alternatives are incrementally eroded. State intervention itself is aimed at not only adjusting to but also sustaining, promoting, and expanding an open global economy in order to capture its perceived