Lettie Conrad: Third Wave Feminism: a Case Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commencement 2006-2011

2009 OMMENCEMENT / Conferring of Degrees at the Close of the 1 33rd Academic Year Johns Hopkins University May 21, 2009 9:15 a.m. Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Divisional Ceremonies Information 6 Johns Hopkins Society of Scholars 7 Honorary Degree Citations 12 Academic Regalia 15 Awards 17 Honor Societies 25 Student Honors 28 Candidates for Degrees 33 Please note that while all degrees are conferred, only doctoral graduates process across the stage. Though taking photos from vour seats during the ceremony is not prohibited, we request that guests respect each other's comfort and enjoyment by not standing and blocking other people's views. Photos ol graduates can he purchased from 1 lomcwood Imaging and Photographic Services (410-516-5332, [email protected]). videotapes and I )\ I )s can he purchased from Northeast Photo Network (410 789-6001 ). /!(• appreciate your cooperation! Graduates Seating c 3 / Homewood Field A/ Order of Seating Facing Stage (Left) Order of Seating Facing Stage (Right) Doctors of Philosophy and Doctors of Medicine - Medicine Doctors of Philosophy - Arts & Sciences Doctors of Philosophy - Advanced International Studies Doctors of Philosophy - Engineering Doctors of Philosophy, Doctors of Public Health, and Doctors of Masters and Certificates -Arts & Sciences Science - Public Health Masters and Certificates - Engineering Doctors of Philosophy - Nursing Bachelors - Engineering Doctors of Musical Arts and Artist Diplomas - Peabody Bachelors - Arts & Sciences Doctors of Education - Education Masters -

Vogue Knitting LIVE Launches in New York City in January

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 6,000 Knitters and Industry “Knitterati” to Gather for New Event Vogue Knitting LIVE Launches in New York City in January. Popular Classes Already Sold Out More than 53 million people know how to knit or crochet—and the number is growing. Following the successful premier of Vogue Knitting LIVE in Los Angeles last year, Vogue Knitting magazine announces a new event at the Hilton New York January 14–16, 2012 . Knitting, an ages-old craft, is taking the world by storm. Professionals, Hollywood A-listers, and rock stars have all joined the ranks of knitters, and Ravelry, a popular social media site for stitchers, boasts close to 2 million members. Its benefits are renown: A Harvard study from 2007 concluded that knitting may be as effective as medication in reducing stress. “We know that knitters love getting together at yarn stores to learn new techniques, compare projects, and hear from top designers. We’ve simply taken that to the next level by creating the largest live gathering of knitters in New York,” says Trisha Malcolm, editor of Vogue Knitting and originator of Vogue Knitting LIVE. Vogue Knitting LIVE caters to knitters at all levels—from the knit-curious to experienced designers and crafters. In 2012, knitters can expect: • More than 75 how-to sessions, some of which are already sold out. Topics like “An Overture to Estonian Lace” and “Working with Antique and Vintage Knitting Patterns” bring 200-year old techniques to new generations. Other sessions such as “Happy Hat Knitting” and “Sock Innovation” focus on specific types of projects. -

Lettuce Knit Arm Warmers

Knitting Needles: 4.5mm [US 7]. Place markers (2), small stitch holder, yarn needle. GAUGE: 19 sts = 4”; 26 Rows = 4” in St st. CHECK YOUR GAUGE. Use any size needle to obtain the gauge. SPECIAL ABBREVIATIONS M1 (make one stitch) = Lift running thread before next stitch onto left needle and knit into the back loop. K1, p1 Rib (worked over an odd number of sts) Row 1 (Right Side): K1, * p1, k1; repeat from * across row. Row 2: P1, * k1, p1; repeat from * across row. Repeat Rows 1 and 2 for K1, p1 rib. ARM WARMERS Right Arm Cast on 41 (45) sts. Cuff Begin with Row 1, work in K1, p1 rib until piece measures 1½”, end by working a wrong side row. Begin Pattern Row 1: P3 (4), k13, p7 (8), k1, p17 (19). Row 2: K17 (19), p1, k7 (8), p13, k3 (4). Row 3: P3 (4), k4tog, [yo, k1] 5 times, yo, k4tog-tbl, p7 (8), k1, p17 (19). Row 4: Repeat Row 2. Repeat Rows 1 - 4 until piece measures 8½” from beginning, then work Rows 1 and 2 once more. Shape Thumb Row 3: P3 (4), k4tog, [yo, k1] 5 times, yo, k4tog-tbl, p7 (8), place marker, M1, k1, M1, place marker, p17 (19)– 43 (47) sts. lettuce knit Row 4: K17 (19), p3, k7 (8), p13, k3 (4). arm warmers Keeping continuity of pattern, continue to inc 1 st after first marker and before second marker every right side row 5 (6) times more, working extra sts into pattern–53 (59) sts; 13 (15) sts SN0111 between markers. -

HOME CRAFTING GUIDE We’Re Still Here for You

WEEK 8 HOME CRAFTING GUIDE We’re still here for you. As we continue to practice social distancing, we’ve pulled together another list of of our current favorite classes on the site. We want to continue to be a resource of creative inspiration as we get through these long days and hope you’ll take some time to start a new project or two. Thanks for being a part of the Creativebug community! Remember... You're more creative than you think! HOME CRAFTING GUIDE 2 WEEK 8 Concept Sketchbook: A Daily Sew the Wanderlust Tee Practice with Lindsay Stripling with Fancy Tiger https://www.creativebug.com/classseries/ https://www.creativebug.com/classseries/ single/concept-sketchbook-a-daily-practice single/sew-the-wanderlust-tee Skill level: Intermediate Skill level: Intermediate Video duration: 1 hour Video duration: 28 min Materials: Materials: - 8 x 8” mixed media sketchbook – Lindsay - XS-L: 1 yard Jersey knit fabric (+ ¼ yard if uses Shinola brand lengthening shirt) - Mechanical pencil - XL – XXL: 1 ¼ yards Jersey knit fabric (+ ¼ - HB pencil yard if lengthening shirt) - Eraser - Sewing machine - Sharpener - Serger (optional but recommended) - Pilot g-tec .4 pen - Double or Twin Needle 4.0 size - Kuratake brush pens - Rotary cutter - Three colored pencils, two similar and - Cutting mat one contrasting - Matching thread - Neocolor II Aquarelle crayons or other - Tape wax or pastel crayons in Malachine Green, - Scratch paper Vermillion, White, Ochre, Salmon and - Marking tool Light Blue - Thread snips - Tracing paper - Pattern weights - 6" x 24" -

Cs Mostra Kurt Cobain E Il Grunge

Al Medimex i Nirvana come non si sono mai visti dal 7 giugno al Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto – MArTA la mostra “Kurt Cobain & Il Grunge: Storia di una Rivoluzione. FotograFie di Michael Lavine e Charles Peterson” I Nirvana come non sono mai stati visti. Ci saranno anche sei scatti inediti nella mostra «Kurt Cobain & Il Grunge: Storia di una Rivoluzione. Fotografie di Michael Lavine e Charles Peterson», in programma dal 7 giugno al 1° luglio al Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto (MarTa), in occasione del Medimex 2018, che quest’anno ha tra gli headliner uno dei gruppi simbolo del post-grunge, i Placebo, attesi venerdì 8 giugno sul palco della Rotonda del Lungomare, dove giovedì 7 arriveranno i padri della musica elettronica Kraftwerk con l’esclusiva italiana del loro spettacolo 3D. Saranno gli eventi dell’International Festival & Music Conference promosso da Puglia Sounds, il programma della Regione Puglia per lo sviluppo del sistema musicale pugliese, che quest’anno propone a Taranto live, attività professionali, incontri d’autore, workshop, esposizioni e, per l’appunto, la mostra «Kurt Cobain & Il Grunge». Dunque, il più importante museo al mondo sulla civiltà magno-greca apre le porte alle testimonianze di un recente passato musicale e costruisce un ponte ideale tra la capitale del Grunge, Seattle, e la città dei due mari, dove nel 1989 transitarono quasi in sordina - per un concerto oggi considerato un evento postumo - i Soundgarden, una delle band rappresentative di quella scena musicale, che la mostra racconta intorno alle immagini dei Nirvana. La mostra, a cura di ONO arte contemporanea, comprende settantotto foto esposte in due sezioni: da un lato trentotto immagini colte da Charles Peterson, che si concentrano sulla storia della nascita dei Nirvana, i concerti live e la scena Grunge, dall’altro quaranta scatti di Michael Lavine estratti da servizi posati e immagini per le riviste. -

Aafjufj Fpjpw^-Itkalfcic BILLY Rtiabrir/ HIATUS ^ ^Mrc ^ ^International

THAT MSAZlNf FKOm CUR UM.* ftR AAfJUfJ fPJpw^-iTKAlfCIC BILLY rtiABrir/ HIATUS ^ ^mrc ^ ^international 06 I 22 Ex-Centric Sound System / Velvet 06 I 23 Cinematic Orchestra DJ Serious 06 I 24 The New Deal / Q DJ Ramasutra 06 I 26 Bullfrog featuring Kid Koala Soulive 06 I 30 Trilok Gurtu / Zony Mash / Sex Mob PERFORMANCE WORKS SRflNUILLE ISLRND 06 ! 24 Cinematic Orchestra BULLFROG 06 1 25 Soulive 06 127 Metalwood ^ L'" x**' ''- ^H 06 1 28 Q 06 1 29 Broken Sound Barrier featuring TRILOK GURTU Graham Haynes + Eyvind Kang 06 130 Kevin Breit "Sisters Euclid" Heinekeri M9NTEYINA ABSOLUT ^TELUS- JAZZ HOTLINE 872-5200 TICKETMASTER 280-4444 WWW.JAZZVANCOUVER.COM PROGRAM GUIDES AT ALL LOWER MAINLAND STARBUCKS, TELUS STORES, HMV STORES THE VANCOUVER SUN tBC$.radiQ)W£ CKET OUTLETS BCTV Music TO THE BEAT OF ^ du Maurier JAZZ 66 WATER STREET VANCOUVER CANADA Events at a glance: \YJUNE4- ^guerilla pres ERIK TRUFFAZ (Blue Note) s Blue Note signed, Parisian-based trumpe t player Doors 9PM/$15/$12 ir —, Sophia Books, Black S — Boomtown, Bassix and Highlife guerilla & SOPHIA Bk,w-> FANTASTIC PLASTIC MACHINE plus TIM 'LOVE' LEE fMfrTrW) editrrrrrrp: Lyndsay Sung gay girls rock the party by elvira b p. 10 "what the hell did i get myself DERRICK CARTER© inSOe drums are an instrument, billy martin by sarka k p. 11 into!!! je-sus chrisssttf!" mirah sings songs, by adam handz p. 12 ad rep/acid kidd: atlas strategic: wieners or wankers? by lyndsay s. p. 13 Maren Hancock Y JUNE 10 - SPECTRUM ENT pres bleepin' nerds! autechre by robert robot p. -

Conroe Independent School District Board of Trustees Official Notice and Agenda Regular Meeting 6:00 PM Tuesday, April 20, 2021

Conroe Independent School District Board of Trustees Official Notice and Agenda Regular Meeting 6:00 PM Tuesday, April 20, 2021 A Regular meeting of the Board of Trustees of the Conroe Independent School District will be held on Tuesday, April 20, 2021, beginning at 6:00 PM in the CISD Administration Building, 3205 W. Davis, Conroe, TX 77304. Members of the public may access the meeting virtually at http://tiny.conroeisd.net/R78KV The subjects to be discussed or considered or upon which any formal action may be taken are as listed below. Items do not have to be taken in the order shown on this meeting notice. I. Opening A. Invocation B. Pledge of Allegiance II. Awards and Recognitions A. Special Board Recognition: 2021 THSWPA 6A 198-lb Weight Class State 4 Champion Ana Gonzalez, Conroe High School B. Special Board Recognition: 2021 UIL Class 6A Girls' Swimming & Diving 5 State Champions The Woodlands High School C. Special Board Recognition: 2021 UIL Class 6A Boys' Swimming & Diving 6 State Champions The Woodlands High School D. Special Board Recognition: 2021 UIL Class 6A Boys' 100-Yard Backstroke 7 State Champion Tyler Hulet, The Woodlands High School E. Special Board Recognition: 2021 UIL Class 6A Boys' 200-Yard Medley 8 Relay State Champions The Woodlands High School F. Special Board Recognition: Teaching & Learning Department COVID-19 9 Response III. Citizen Participation 11 IV. Consent Agenda A. Consider Approval of Minutes 12 B. Consider Amendment to the 2020-2021 Budget 18 C. Receive Human Resources Report and Consider Employment of 27 Professional Personnel D. -

“We ARE the Revolution”: Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing

Women's Studies An inter-disciplinary journal ISSN: 0049-7878 (Print) 1547-7045 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gwst20 “We ARE the Revolution”: Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing KEVIN DUNN & MAY SUMMER FARNSWORTH To cite this article: KEVIN DUNN & MAY SUMMER FARNSWORTH (2012) “We ARE the Revolution”: Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing, Women's Studies, 41:2, 136-157, DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2012.636334 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2012.636334 Published online: 11 Jan 2012. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1979 View related articles Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gwst20 Download by: [University of Warwick] Date: 25 October 2017, At: 11:38 Women’s Studies, 41:136–157, 2012 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0049-7878 print / 1547-7045 online DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2012.636334 “WE ARE THE REVOLUTION”: RIOT GRRRL PRESS, GIRL EMPOWERMENT, AND DIY SELF-PUBLISHING KEVIN DUNN and MAY SUMMER FARNSWORTH Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva Punk rock emerged in the late 20th century as a major disruptive force within both the established music scene and the larger capitalist societies of the industrial West. Punk was generally characterized by its anti-status quo disposition, a pronounced do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, and a desire for disalienation (resis- tance to the multiple forms of alienation in modern society). These three elements provided actors with tools for political inter- ventions and actions. -

Mixed Race Capital: Cultural Producers and Asian American Mixed Race Identity from the Late Nineteenth to Twentieth Century

MIXED RACE CAPITAL: CULTURAL PRODUCERS AND ASIAN AMERICAN MIXED RACE IDENTITY FROM THE LATE NINETEENTH TO TWENTIETH CENTURY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Stacy Nojima Dissertation Committee: Vernadette V. Gonzalez, Chairperson Mari Yoshihara Elizabeth Colwill Brandy Nālani McDougall Ruth Hsu Keywords: Mixed Race, Asian American Culture, Merle Oberon, Sadakichi Hartmann, Winnifred Eaton, Bardu Ali Acknowledgements This dissertation was a journey that was nurtured and supported by several people. I would first like to thank my dissertation chair and mentor Vernadette Gonzalez, who challenged me to think more deeply and was able to encompass both compassion and force when life got in the way of writing. Thank you does not suffice for the amount of time, advice, and guidance she invested in me. I want to thank Mari Yoshihara and Elizabeth Colwill who offered feedback on multiple chapter drafts. Brandy Nālani McDougall always posited thoughtful questions that challenged me to see my project at various angles, and Ruth Hsu’s mentorship and course on Asian American literature helped to foster my early dissertation ideas. Along the way, I received invaluable assistance from the archive librarians at the University of Riverside, University of Calgary, and the Margaret Herrick Library in the Beverly Hills Motion Picture Museum. I am indebted to American Studies Department at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa for its support including the professors from whom I had the privilege of taking classes and shaping early iterations of my dissertation and the staff who shepherded me through the process and paperwork. -

One to One Performance a Study Room Guide on Works Devised for an ‘Audience of One’

One to One Performance A Study Room Guide on works devised for an ‘audience of one’ Compiled & written by Rachel Zerihan 2009 LADA Study Room Guides As part of the continuous development of the Study Room we regularly commission artists and thinkers to write personal Study Room Guides on specific themes. The idea is to help navigate Study Room users through the resource, enable them to experience the materials in a new way and highlight materials that they may not have otherwise come across. All Study Room Guides are available to view in our Study Room, or can be viewed and/or downloaded directly from their Study Room catalogue entry. Please note that materials in the Study Room are continually being acquired and updated. For details of related titles acquired since the publication of this Guide search the online Study Room catalogue with relevant keywords and use the advance search function to further search by category and date. Cover image credit: Ang Bartram, Tonguing, Centro de Documentacion, Ex Teresa Arte Actual, photographer Antonio Juarez, 2006 Live Art Development Agency Study Room Guide on ONE TO ONE PERFORMANCE BY RACHEL ZERIHAN and OREET ASHERY FRANKO B ANG BARTRAM JESS DOBKIN DAVIS FREEMAN/RANDOM SCREAM ADRIAN HOWELLS DOMINIC JOHNSON EIRINI KARTSAKI LEENA KELA BERNI LOUISE SUSANA MENDES-SILVA KIRA O’REILLY JIVA PARTHIPAN MICHAEL PINCHBECK SAM ROSE SAMANTHA SWEETING MARTINA VON HOLN 1 Contents Page No. Introduction What is a “One to One”? 3 How Might One Trace the Origins of One to One Performance? 4 My Approach in Making -

Riot Dyke: Music, Identity, and Community in Lesbian Film

i Riot Dyke: Music, Identity, and Community in Lesbian Film by Alana Kornelsen A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, ON © 2016 Alana Kornelsen ii Abstract This thesis examines the use of diegetic pre-composed music in three American lesbian feature films. Numerous trends can be noted in the selection of music in lesbian film broadly— music is often selected to draw on insider knowledge of the target audience of these films, creating cachet. This cachet comes with accompanying “affiliating identifications” (Kassabian 2001) that allow music to be used in the films’ construction of characters’ identities. This is evident in the treatment of music in many lesbian films: characters frequently listen to, discuss, and perform music. This thesis focuses specifically on riot grrrl music and the closely linked genre of queercore (which together Halberstam ([2003] 2008) refers to as “riot dyke”) in three films that focus on the lives of young women: The Incredibly True Adventure of Two Girls in Love (dir. Maria Maggenti, 1995), All Over Me (dir. Alex Sichel, 1997), and Itty Bitty Titty Committee (dir. Jamie Babbit, 2007). By examining how diegetic riot dyke music is used in these three films to build characters’ identities and contribute to the films’ narratives I argue that in these films, riot dyke music is presented as being central to certain queer identities and communities, and that this music (as well as the community that often accompanies it) is portrayed as instigating or providing opportunities for characters’ personal growth and affirming characters’ identities in adverse environments. -

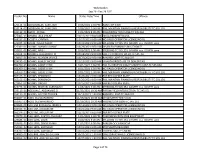

Web Docket Aug 4

Web Docket Sep 29 - Dec 29 2021 Docket No Name Status Date/Time Offense E25114 01 ABDELMALAK, SAMI ZAKI 10/6/2021 1:30 PM RAN STOP SIGN E25114 02 ABDELMALAK, SAMI ZAKI 10/6/2021 1:30 PM FAIL MAINTAIN FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY TC 601.191 041138 01 ABDIN, JOYNAL 11/2/2021 9:00 AM FOLLOWING TOO CLOSE-TC 545.062 575405 01 ABRAM, JALA SHA NE 10/12/2021 9:00 AM DRUG PARAPHERNALIA 566157 01 ACOSTA, CYNTHIA 12/17/2021 9:00 AM NO VALID OPERATOR LICENSE/NO DL E23925 01 ADAM, NAZAR MAJDI 10/15/2021 9:00 AM SPEEDING-TC 545.351 68 MPH in a 45 MPH zone E25389 01 ADAME, AMANDA MARIE 10/29/2021 9:00 AM DISABLED PARKING-UNAUTHORIZE E25651 01 ADAME, ARIS I 10/6/2021 9:00 AM SPEEDING-TC 545.351 64 MPH in a 45 MPH zone E23164 01 ADAMES, ALEJANDRO III 10/18/2021 9:00 AM FAIL TO CONTROL SPEED-TC 545.351 574817 01 ADAMS, ALLYSON JANYCE 10/29/2021 9:00 AM RAN RED LIGHT-TC 544.007 E24195 01 ADAMS, ASHLEY NICOLE 11/12/2021 9:00 AM UNAUTHORIZED USE OF DEALER TAG 560269 01 ADAMS, CASSIE LYNN 10/1/2021 1:30 PM FAIL TO DRIVE IN SINGLE MARKED LANE-TC 545.060 560269 02 ADAMS, CASSIE LYNN 10/1/2021 1:30 PM NO VALID OPERATOR LICENSE/NO DL 560269 03 ADAMS, CASSIE LYNN 10/1/2021 1:30 PM FAIL MAINTAIN FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY TC 601.191 565166 01 ADAMS, DEMONICA 10/26/2021 9:00 AM EXPIRED LICENSE PLATE 565166 02 ADAMS, DEMONICA 10/26/2021 9:00 AM FAIL MAINTAIN FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY TC 601.191 E23852 01 ADAMS, LINDA R 10/15/2021 9:00 AM EXPIRED LICENSE PLATE E23776 01 ADAMS, MICHAEL GLENNDALE 11/8/2021 9:00 AM SPEEDING-TC 545.351 44 MPH in a 30 MPH zone 550113 01 ADEKUNLE,