MHA TOC OGS.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pacific Circle

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII UMA<W THE PACIFIC CIRCLE OCTOBER 2002___________ BULLETIN NO. 9_____________ISSN 1520-3581 CONTENTS PACIFIC CIRCLE NEW S ................................................................ 2 Members’ N ew s ...............................................................................2 Recent Meetings...............................................................................4 Publications...................................................................................... 5 IUHPS/DHS NEW S .............................................................................6 HSS N E W S ..............................................................................................7 PSA N E W S ..............................................................................................8 PACIFIC WATCH ............................................................................... 8 CONFERENCE AND SOCIETY REPORTS ......................... 10 FUTURE CONFERENCES & CALLS FOR PAPERS .. .11 EXHIBITIONS AND MUSEUMS ............................................... 13 EMPLOYMENT, GRANTS AND PRIZES .............................. 13 RESEARCH, ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS: PRINT & ELECTRONIC .............................................................. 15 BOOK AND JOURNAL NEWS ..................................................16 BOOK REVIEWS .............................................................................17 PACIFIC BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................... 27 ^ecen* B°°ks ..................................................................................27 -

Rupture Across Arc Segment and Plate Boundaries in the 1 April 2007 Solomons Earthquake

LETTERS Rupture across arc segment and plate boundaries in the 1 April 2007 Solomons earthquake FREDERICK W. TAYLOR1*, RICHARD W. BRIGGS2†, CLIFF FROHLICH1, ABEL BROWN3, MATT HORNBACH1, ALISON K. PAPABATU4, ARON J. MELTZNER2 AND DOUGLAS BILLY4 1Institute for Geophysics, John A. and Katherine G. Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas at Austin, Texas 78758-4445, USA 2Tectonics Observatory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91125, USA 3School of Earth Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210, USA 4Dept. of Mines, Energy, and Water Resources, PO Box G37, Honiara, Solomon Islands †Present address: US Geological Survey, MS 966, Box 25046, Denver, Colorado 80225, USA *e-mail: [email protected] Published online: 30 March 2008; doi:10.1038/ngeo159 The largest earthquakes are generated in subduction zones, residual strain accumulates along the ‘locked’ plate boundary until and the earthquake rupture typically extends for hundreds of it is released seismically. Previous historical earthquakes near the kilometres along a single subducting plate. These ruptures often 1 April rupture area in the Solomon Islands had magnitudes M begin or end at structural boundaries on the overriding plate that of 7.2 and less5. This was puzzling because Chile and Cascadia, are associated with the subduction of prominent bathymetric where extremely young oceanic crust also subducts, have produced 1,2 features of the downgoing plate . Here, we determine uplift exceptionally large earthquakes (MW ≥ 9.0) (refs 6,7). The 1 April and subsidence along shorelines for the 1 April 2007 moment earthquake confirms that in the western Solomons, as in Chile and magnitude MW 8.1 earthquake in the western Solomon Islands, Cascadia, subducted young ridge-transform material is strongly using coral microatolls which provide precise measurements coupled with the overlying plate. -

Leg TWO Points

2017 Iron Butt Rally, Leg 2 Allen, TX to Allen, TX Packing List Leg 2 Bonus Pack – Allen, TX to Allen, TX Claimed Bonuses Form Ask Rallymaster if there are any changes or corrections Before leaving the checkpoint, make sure you can find each bonus location and have a clear understanding of what is required to earn the bonus WARNING: DO NOT LEAVE ON A LEG UNTIL YOU HAVE VERIFIED THAT ALL PAPERWORK IS IN YOUR RALLY PACKAGE FOR THAT LEG. EACH PAGE IS NUMBERED. THIS IS YOUR RESPONSIBILITY. CRITICAL: Please be respectful when placing your flag in photos. Private property and priceless museum pieces must not be used as your flag support. To earn any bonus, you MUST claim it on the Claimed Bonuses form. This includes Rest bonuses and Call-In bonuses. If you lose the Claimed Bonuses form, you will earn no bonus points for the leg. REMEMBER: Unless otherwise specified, I.D. Flags are required in all photos. Page 1 of 12 Scoring Instructions All bonuses are available at point values listed in this pack within the time restrictions listed in the rally book. Bonuses in the rally book are divided into five categories: Air, Land, Mythical, Prehistoric, and Water. Those categories are denoted in the bonus codes by the first letter of the code. For example, the “A” in code “ABB” indicates this as an “Air” bonus. Riders who successfully visit and claim four(4) bonuses in a row from different categories will earn triple (3x) the listed value of the fourth bonus in that string of four. -

A Cross-Sectoral Approach

A Cross-Sectoral Approach A . A£ O O e AvAg a* n e- e- o- Malaria and Development in Africa A Cross-Sectoral Approach American Association for the Advancement of Science Sub-Saharan Africa Program Under Cooperative Agreement with U.S. Agency for International Development Africa Bureau No. AFR-0481-A-00-0037-00 September 1991 Table of Contents Foreword ............................................................. v Executive Summary ....................................................ix Introduction MalariaandDevelopmentinAfrica:A Cross-SectoralApproach................ 1 Background Mala,'ia in Sub-Saharan Africa ........................................... 5 Report Recommendations ...................... ........................ 9 L Broaden Attack on Malaria by Strengthening Cross-Sectoral Cooperation for MalariaControl ..................... ...................... 11 Background ................................................ 11 Actions for National Governments .............................. 11 Actions for Donors .......................................... 13 Support Existing Cross-Sectowrl Cooperation in Sub-Saharan Africa ...13 I. Utilize Criss-SectoralApproahandResources to CombatMlaria Associated with Development Efforts .............................. 15 Potential Impact of Resource Development Projects on Malaria ............................................... 15 Example: Irrigation Development and Malaria Incidence in Zanzibar .. 15 Opportunities for Control of Malaria Associated with Development Efforts ..................................... -

The Naturalist and His 'Beautiful Islands'

The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lawrence, David (David Russell), author. Title: The naturalist and his ‘beautiful islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific / David Russell Lawrence. ISBN: 9781925022032 (paperback) 9781925022025 (ebook) Subjects: Woodford, C. M., 1852-1927. Great Britain. Colonial Office--Officials and employees--Biography. Ethnology--Solomon Islands. Natural history--Solomon Islands. Colonial administrators--Solomon Islands--Biography. Solomon Islands--Description and travel. Dewey Number: 577.099593 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: Woodford and men at Aola on return from Natalava (PMBPhoto56-021; Woodford 1890: 144). Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgments . xi Note on the text . xiii Introduction . 1 1 . Charles Morris Woodford: Early life and education . 9 2. Pacific journeys . 25 3 . Commerce, trade and labour . 35 4 . A naturalist in the Solomon Islands . 63 5 . Liberalism, Imperialism and colonial expansion . 139 6 . The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital . 169 7 . Expansion of the Protectorate 1898–1900 . -

Pacific Islands Herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 11 Article 1 Number 3 – Number 4 12-29-1951 Pacific slI ands herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A check list of species Vasco M. Tanner Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Vasco M. (1951) "Pacific slI ands herpetology, No. V, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. A check list of species," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 11 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol11/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. U8fW Ul 22 195; The Gregft fiasib IfJaturalist Published by the Department of Zoology and Entomology Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Volume XI DECEMBER 29, 1951 Nos. III-IV PACIFIC ISLANDS HERPETOLOGY, NO. V GUADALCANAL, SOLOMON ISLANDS: l A CHECK LIST OF SPECIES ( ) VASCO M. TANNER Professor of Zoology and Entomology Brigham Young University Provo, Utah INTRODUCTION This paper, the fifth in the series, deals with the amphibians and reptiles, collected by United States Military personnel while they were stationed on several of the Solomon Islands. These islands, which were under the British Protectorate at the out-break of the Japanese War in 1941, extend for about 800 miles in a southeast direction from the Bismarck Archipelago. They lie south of the equator, between 5° 24' and 10° 10' south longitude and 154° 38' and 161° 20' east longitude, which is well within the tropical zone. -

E Abstracts with Advt 12.02.2019

International Conference ee ABSTRACTSABSTRACTS Goa, 13th - 16th February, 2019 Organizers Society for Vector Ecology (Indian Region) and ICMR - National Institute of Malaria Research, FU, Goa I N D E X S.No. Name of the Delegate Page No. S.No. Name of the Delegate Page No. 1 A. N. Anoopkumar 45 42 Narayani Prasad Kar 50 2 Agenor Mafra-Neto 40 43 Naren babu N 63 3 Ajeet Kumar Mohanty 72 44 Naveen Rai Tuli 10-11 4 Alex Eapen 17 45 Neil Lobo 23 5 Algimantas Paulauskas 33 46 Nidhish G 65 6 Aneesh Embalil Mathachan 46 47 Norbert Becker 12 7 Aneesh Embalil Mathachan 28 48 O.P. Singh 78 8 Anju Viswan K 64 49 P. K. Rajagopalan 2-9 9 Ankita Sindhania 62 50 P. K. Sumodan 30 10 Ashwani Kumar 25 51 Paulo F. P. Pimenta 27 11 Ayyadevera Rambabu 29 52 Poonam Singh 90 12 Bhavana Gupta 43 53 Pradeep Kumar Shrivastava 20 13 Charles Reuben Desouza 89 54 R. S. Sharma 22 14 Dan Kline 37 55 R.K. Dasgupta 21 15 Deepa Jha 61 56 Rajendra Thapar 76 16 Deeparani K. Prabhu 68 57 Rajnikant Dixit 74 17 Devanathan Sukumaran 82 58 Rajpal Singh Yadav 1 18 Devi Shankar Suman 16 59 Raju Parulkar 84 19 Farah Ishtiaq 36 60 Rakhi Dhawan 73 20 Gourav Dey 88 61 Ramesh C Dhiman 32 21 Gunjan Sharma 86 62 Ranjana Rani 42 22 Hanno Schmidt 18 63 Roop Kumari 19 23 Hemachandra Bhovi 75 64 S. R. Pandian 49 24 Hemanth Kumar 53 65 Sajal Bhattacharya 31 25 Jagbir Singh 34 66 Sam Siao Jing 77 26 Jitender Gawade 83 67 Sanchita Bhattacharaya 56 27 John E. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

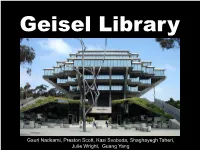

Geisel Library

Geisel Library Gauri Nadkarni, Preston Scott, Kasi Svoboda, Shaghayegh Taheri, Julie Wright, Guang Yang Introduction Typology: University Central Library Architect: William L. Pereira Location: University of California, San Diego (La Jolla, California) Date: 1970 Area: 255,000 sqft Dedicated to Audrey & Theodore Seuss Geisel (Dr. Seuss) in 1995 Background Campus Master Plan The Architect: William L. Pereira Born: April 25, 1909; Chicago, Illinois Education: University of Illinois (1931) Career: Started 3 architectural firms over his life lifetime Movie making business Professor of architecture at University of Southern California Style: Brutalist Functionalist Pre-Cast Concrete Design Concept Program: 3,000 readers 2,500,000 books Design Concept Forum 16 columns Design Concept Forum Design Concept Below Forum Public Floor Main entrance Staff areas Library Services Basement Staff areas Mechanical Design Concept Below Forum Design Concept Above Forum 5 Floors Book collection Study areas Elliptical in Section “Circular” in Plan Design Concept Above Forum: 1st level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 2nd level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 3rd level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 4th level of stacks Design Concept Above Forum: 5th level of stacks Choice of structural material Reinforced Hybrid Steel- Steel structure Concrete with four large steel concrete structure structure trusses supporting the With concrete up to steel With external 16 sloped third floor of spheroid, trusses beam –column concealed in the Laterally tied at lower second floor. three spheroid by post- tensioned beams. •Factors influencing the choice of Reinforced Concrete construction •Increasing rate of steel and extensive use of steel in the truss. nd •Reduced flexibility of space at 2 level of the spheroid. -

An Otago Storeman in Solomon Islands

AN OTAGO STOREMAN IN SOLOMON ISLANDS The diary of William Crossan, copra trader, 1885–86 AN OTAGO STOREMAN IN SOLOMON ISLANDS The diary of William Crossan, copra trader, 1885–86 Edited by Tim Bayliss-Smith Reader in Pacific Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England, UK and Judith A. Bennett Professor of History, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand Aotearoa Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: An Otago storeman in Solomon Islands : the diary of William Crossan, copra trader, 1885-86 / edited by Tim Bayliss-Smith and Judith A. Bennett. ISBN: 9781922144201 (pbk.) 9781922144218 (ebook) Subjects: Crossan, William. Copra industry--Solomon Islands--History. Merchants--New Zealand--Biography. New Zealand--History--19th century. Solomon Islands--History--19th century. Other Authors/Contributors: Bayliss-Smith, Tim. Bennett, Judith A., 1944- Dewey Number: 993.02 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents List of Figures ..................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................. ix Introduction: Islands traders and trading .................. 1 1. William Crossan ................................... 7 2. Makira islanders and Europeans ...................... 15 3. Chiefs and traders ................................. 27 4. Crossan’s Hada Bay Diary ........................... 37 Appendix 1. ‘My Dearest Aunt’ ......................... 85 Appendix 2. -

The British Army's Contribution to Tropical Medicine

ORIGINALREVIEW RESEARCH ClinicalClinical Medicine Medicine 2018 2017 Vol Vol 18, 17, No No 5: 6: 380–3 380–8 T h e B r i t i s h A r m y ’ s c o n t r i b u t i o n t o t r o p i c a l m e d i c i n e Authors: J o n a t h a n B l a i r T h o m a s H e r r o nA a n d J a m e s A l e x a n d e r T h o m a s D u n b a r B general to the forces), was the British Army’s first major contributor Infectious disease has burdened European armies since the 3 Crusades. Beginning in the 18th century, therefore, the British to tropical medicine. He lived in the 18th century when many Army has instituted novel methods for the diagnosis, prevention more soldiers died from infections than were killed in battle. Pringle and treatment of tropical diseases. Many of the diseases that observed the poor living conditions of the army and documented are humanity’s biggest killers were characterised by medical the resultant disease, particularly dysentery (then known as bloody ABSTRACT officers and the acceptance of germ theory heralded a golden flux). Sanitation was non-existent and soldiers defecated outside era of discovery and development. Luminaries of tropical their own tents. Pringle linked hygiene and dysentery, thereby medicine including Bruce, Wright, Leishman and Ross firmly contradicting the accepted ‘four humours’ theory of the day. -

A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego Janet Weber Tigard Public Library

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CommonKnowledge Volume 17 , Number 1 Library Wonders and Wanderings: Travels Near and Far (Spring 2011) | Pages 4 July 2014 A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego Janet Weber Tigard Public Library Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.pacificu.edu/olaq Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Weber, J. (2014). A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego. OLA Quarterly, 17(1), 4. http://dx.doi.org/10.7710/ 1093-7374.1308 © 2014 by the author(s). OLA Quarterly is an official publication of the Oregon Library Association | ISSN 1093-7374 | http://commons.pacificu.edu/olaq A Visit to the Dr. Seuss Archives at UC San Diego by Janet Weber bout ten years ago when I was conducting research on Dr. Seuss, I discovered that [email protected] his archives were housed at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) in La Youth Services Librarian Jolla. Since then I’ve wanted to go visit the collection. Little did I know that my dream Tigard Public Library A to visit would come true many years later as a member of the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Special Collections and Bechtel Fellowship Committee. My committee had the opportunity to visit the Dr. Seuss archives during ALA Midwinter in January 2011. Dr. Seuss, also known as Theodore Geisel, was a long time resident of La Jolla up until For more information on his death in 1991.