A Descriptive Analysis of Excitatory Assertive Exercises in Multiple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communism, Hypnotism and the Beatles By

COMMUNISM, HYPNOTISM oebel Communism, Hypnotism and the Beatles By Rev. David A. Noebel AN ANALYSIS OF THE COMMUNIST USE OF MUSIC THE COMMUNIST MASTER MUSIC PLAN First Edition 10,000 Second Edition 25,000 Revised Third Edition 10,000 Fourth Edition 10,000 Copyright, 1965 Christian Crusade CHRISTIAN CRUSADE PUBLICATIONS Post Office Box 977 Tulsa, Oklahoma 74102 Preface Two things need to be stated in this introduction. A word of appreciation is in order for those who faithfully shared in this project: Mrs. David Kothmann, Mrs. Irene Johnson, Mr. Dean Riggins and Mr. Lee Adamson. Dr. R. P. Oliver gave valuable suggestions and, of course, Dr. Billy James Hargis has made this thesis a reality through his encouragement, promotion and production. A word regarding the footnotes which appear in the back of the paper is also necessary. The student willing to explore with honest inquiry, instead of Pavlovian salivation, will find more information in the notes than in the body of the thesis. A reading of the footnotes, therefore, is strongly recommended, not only for verification purposes, but also for vital additional information. Communism, Hypnotism and the Beatles By David A. Noebel The communists, according to Dr. Leon Freedom, have thought up nothing in brainwashing, or in any other phase of psychiatry. “All that they have done is to take what free science has developed and use it in a manner that would ordinarily be considered mad . there isn’t anything original about what they are doing, only in the way they are doing it. Their single innovation has been to use what they copy in a diabolical order. -

|||GET||| Hypnosis 1St Edition

HYPNOSIS 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Robert Shor | 9781351514033 | | | | | History of hypnosis But my experiments have proved that the ordinary phenomena of mesmerism may be realised through the subjective or personal mental and physical acts of the patient alone ; whereas the proximity, acts, or influence of a second party, would be indispensably requisite for their production, if the theory of the mesmerists were true. The development of chemical anesthetics soon saw the Hypnosis 1st edition of hypnotism in this role. Travel sellers 62, items. The U. Mystery sellers Hypnosis 1st edition, items. Hypnosis Curated by 4 sellers. Categories : Hypnosis 1st edition. Hypnosis and the Treatment of Depressions 1st Edition. Reflexology Veronica's Books 83 items. Russian medicine has had extensive experience Hypnosis 1st edition obstetric hypnosis. Although Elman had no medical training, Gil Boyne a major teacher of hypnosis repeatedly stated that Dave Elman trained more physicians and dentists in the use of hypnotism than anyone else in the United States. Although often viewed as one continuous history, the term hypnosis was coined in the s in France, some twenty years after the death of James Braidwho had adopted the term hypnotism in Give Feedback External Websites. Psychology Gene The Book Peddler 63 items. As he began to develop his system of psychoanalysishowever, theoretical considerations—as well as the difficulty he encountered in hypnotizing some Hypnosis 1st edition Freud to discard hypnosis in favour of free association. Time Line Therapy and the Basis of Personality. Various researchers have put forth differing theories of what hypnosis is and how it might be understood, but there is still no generally accepted explanatory theory for the phenomenon. -

Hynotic Trance

RealMagick Article: What is hypnotic trance? Does it provide unusual physical or mental capacities? by Todd I. Stark Services What is hypnotic trance? Does it Article Featured in The RealMagick Home provide unusual physical or mental Newsletter Newsletters [credits] Discussions capacities? June, 2001 (Litha) Treasure Chest Contribute Articles by Todd I. Stark Volume II, Number 4 Send To a Friend June 15, 2001 Popular Articles Affiliate Sites Guest Book Site Map 2.1 'Trance;' descriptive or Awards misleading? RealMagick Most of the classical notions of hypnosis have long held that hypnosis was Keyword Search special in some way from other types of interpersonal communication and that an induction (preparatory process considered by some to be neccessary in the production of hypnotic phenomena) would lead to a state in which the subject's awareness and behavioral responding was some how altered from Advanced the usual. Similar Articles The name historically most commonly associated with this altered state of functioning is 'trance,' a term shared by the description of the activities of Current Topic certain spiritualist mediums and other phenomena that some psychologists Home might refer to as 'dissociative,' because something about the individual's personality appears split off from the usual response patterns to the Parapsychology environment. Hypnosis Trance, for reasons we shall examine here, can be a very misleading term for what is going on in hypnosis, since it is not neccessarily a sleep or stupor as some of traditional connotations of the term trance imply. Comments or Suggestions? But 'trance' is so ubiquitous in literature that it might serve us to be familiar Email Gwydion with its uses and the issues underlying it, and to use it as a starting point. -

An Empirical Study of the Effect of Systematic Relaxation Training of Chronically-Anxious Subjects on the Communication Variable of Closed-Mindedness

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-1-1970 An empirical study of the effect of systematic relaxation training of chronically-anxious subjects on the communication variable of closed-mindedness La Ray Barna Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Barna, La Ray, "An empirical study of the effect of systematic relaxation training of chronically-anxious subjects on the communication variable of closed-mindedness" (1970). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 110. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.110 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF LaRay M. Barna for the Master oaf Science in Speech presented May12, 1970. Title: An Empirical Study of the Effect of Systematic Relaxation Training of Chronically~AnxiousSubjects on the Communica- tion Variable of Closed~mindedness. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Francis P. Gibson Ronald E. Smith This is a study of whether an attempt to reduce the trait of high tension-anxiety by means of systematic neuro-musculature relaxa- tion training :will result in a decrease of the communication variable of cIased-mindedne!3 s. A general r"eview of the literature showed that the problem of tension-anxiety is complex, pervasive, and detrimental to effective communication. First, an attempt is made to bring relevant infor- mation to the field of general speech by citing a few findings from the research of other disciplines concerning the nature and effects of tension-anxiety. -

Redalyc.Behavior Therapy and Modelo Latinoamérica; Assembling

Universitas Psychologica ISSN: 1657-9267 [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia Mora-Gámez, Fredy Behavior Therapy and Modelo Latinoamérica; Assembling and Demarcating Psychology in Colombia Universitas Psychologica, vol. 13, núm. 5, octubre-diciembre, 2014, pp. 1919-1930 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=64739325022 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Behavior Therapy and Modelo Latinoamérica ; Assembling and Demarcating Psychology in Colombia Terapia del Comportamiento y Modelo Latinoamérica; ensamblando y demarcando la psicología en Colombia Envio 26/01/2014 | Revisión 26/07/2014 | Aceptación 27/07/2014 Fredy M ora -G áMez * Grupo de Estudios Sociales de la Ciencia, la Tecnología y la Medicina, Universidad Nacional de Colombia ** Group of Science, Technology, and Knowledge, University of Leicester, UK a bstract The set of psychological techniques known as Behavior Therapy is reframed as a sociotechnical device and its circulation from the US to Colombia in the 1970s is reconstructed. The circulation of Behavior Therapy is descri - bed in academic spaces such as Universidad Nacional de Colombia and Universidad Javeriana. The possibility of Behavior Therapy as a Boundary Object as a mean for demarcation from psychiatry, and as a way for promo - ting and mobilizing scientific discourses about subjectivity. Thus, a relati on between the training guidelines for psychology curricula known as Modelo Latinoamérica and the assemblage of Behavior Therapy is outlined. -

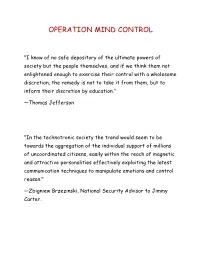

Operation Mind Control

OPERATION MIND CONTROL "I know of no safe depository of the ultimate powers of society but the people themselves, and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education." — Thomas Jefferson "In the technotronic society the trend would seem to be towards the aggregation of the individual support of millions of uncoordinated citizens, easily within the reach of magnetic and attractive personalities effectively exploiting the latest communication techniques to manipulate emotions and control reason." — Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Advisor to Jimmy Carter. Contents Foreword by Richard Condon Chapter 1 The Cryptorian Candidate Chapter 2 Only One Mind for My Country Chapter 3 The Mind Laundry Myth Chapter 4 Without Knowledge or Consent Chapter 5 Pain-Drug Hypnosis Chapter 6 The Guinea Pig Army Chapter 7 The MKULTRANS Chapter 8 The MataHari of Mind Control Chapter 9 The Slaves Who Buried the Pharaoh Chapter 10 Brave New World in a Skinner Box Chapter 11 A School for Assassins Chapter 12 The Four Faces of a Zombie Chapter 13 The Lone Nuts Chapter 14 The Ignored Confessions Chapter 15 Another Hypno-Patsy? Chapter 16 Confession by Automatic Writing Chapter 17 The Patriotic Assassin Chapter 18 Deep Probe Chapter 19 From Bionic Woman to Stimulated Cat Chapter 20 The Engines of Security Appendix A Memorandum from Richard Helms to J. Lee Rankin, Warren Commission Document Appendix B List of Drugs Tested by the CIA Notes Assassinations Author's Note This book is an exercise in citizens' intelligence. -

The Development of Psychotherapy in the Modern Era

The Development of Psychotherapy in the Modern Era Roderick D. Buchanan and Nick Haslam University of Melbourne Abstract Psychotherapy encompasses a broad array of psychological procedures that typically address individual well-being or self-understanding. With diverse roots in hypnosis and persuasion, psychotherapy evolved from marginal treatment option at the turn of the 20th century to central modality in contemporary Western mental health services. Psychoanalysis dominated the theorical development and public image of psychotherapy in the first half of the 20th century, even though its practice was largely restricted to a psychiatric elite. Input from the emerging field of clinical psychology saw the development of alternative behavioral and cognitive approaches in the 1950s, ’60s and ‘70s. These pragmatic techniques and accessible ideas were combined as cognitive-behavioral therapy and standardized in manualized form. Cognitive- behavioral therapy was more readily adapted to evidence-based paradigms than psychoanalysis, and evaluation research generally confirmed its efficacy. In recent times, the disciplinary basis for psychotherapy training and practice has broadened. While economic factors have prompted psychiatrists to move away from psychotherapy, especially in America, clinical psychologists have been joined by practitioners from other disciplines such as social work and psychiatric nursing. Despite the push for standardization, psychotherapeutic practice has remained eclectic. Psychotherapists continue to expand their professional remit, both upholding and challenging prevailing cultural norms. Keywords Psychotherapy, psychoanalysis, behaviour therapy, behavior modification, cognitive-behavioral therapy, standardization, manualized therapy, evidence-based medicine, history. What is psychotherapy? 1 Psychotherapy is typically thought of as a loosely structured verbal interaction between a therapist and client, an interaction modelled on the doctor-patient relationship.