Canis Canem Edit)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TESIS: Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto Y Contexto En Los Videojuegos Como

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES ACATLÁN Grand Theft Auto IV. Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Tesis para obtener el título de: Licenciado en Comunicación PRESENTA David Mendieta Velázquez ASESOR DE TESIS Mtro. José C. Botello Hernández UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Grand Theft Auto IV Impacto y contexto en los videojuegos como parte de la cultura de masas Agradecimientos A mis padres. Gracias, papá, por enseñarme valores y por tratar de enseñarme todo lo que sabías para que llegara a ser alguien importante. Sé que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de tu familia. Mamá, gracias por todo el apoyo en todos estos años; sé que tu esfuerzo es enorme y en este trabajo se refleja solo un poco de tus desvelos y preocupaciones. Gracias por todo tu apoyo para la terminación de este trabajo. A Ariadna Pruneda Alcántara. Gracias, mi amor, por toda tu ayuda y comprensión. Tu orientación, opiniones e interés que me has dado para la realización de cualquier proyecto que me he propuesto, así como por ser la motivación para seguir adelante siempre. -

El “Crunch” En La Industria De Los Videojuegos

El “crunch” en la industria de los videojuegos Autor: Jesús Moreno Calatayud Tutor: Juan Carlos Redondo Gamero Titulación: Grado en Relaciones Laborales y Recursos Humanos Curso: 2019/2020 ÍNDICE 1. ¿Por qué este trabajo de fin de grado? 2. Objetivos. 3. Marco teórico. a. Tipos de estudios. b. El equipo de desarrollo c. ¿Cuánto cuesta hacer un videojuego? d. Como se hace un videojuego. e. Calendario de lanzamientos. f. Los retrasos. g. ¿Que lleva a un estudio a hacer “crunch”? h. ¿Qué supone trabajar en un estudio de videojuegos? i. ¿Todos los estudios hacen “crunch”? 4. ¿Qué ocurre entonces? a. ¿El Crunch, por qué? b. Las consecuencias y la responsabilidad empresarial. 5. La legislación en cuanto al desarrollo de videojuegos. a. Unión Europea b. España c. Francia d. Reino Unido e. Alemania f. Estados Unidos g. Canadá h. Japón 6. Conclusiones. 7. Bibliografía. 1 2 1 ¿Por qué este trabajo de fin de grado? Desde que era pequeño he crecido en contacto con los videojuegos, siempre me he sentido interesado en el mundo de los videojuegos, he crecido con juegos y he leído de la problemática y la visión negativa que tienen los videojuegos de violentos y otros estereotipos y al mismo tiempo he podido experimentar de propia mano lo erróneo de estos estereotipos. Y ahora, gracias al grado de Relaciones Laborales y Recursos Humanos me he sentido interesado por el contexto laboral de este nuevo mercado, por eso mismo este trabajo de fin de grado es tanto la manera de poner en práctica mucho de lo aprendido como una oportunidad de aprender del mercado de los videojuegos con el que he crecido y relacionarlo con lo que he aprendido durante estos 4 años. -

Zeitschrift Für Kanada-Studien

Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien Im Auftrag der Gesellschaft für Kanada-Studien herausgegeben von Katja Sarkowsky Martin Thunert Doris G. Eibl 36. Jahrgang 2016 Herausgeber der Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien (ZKS) ist die GESELLSCHAFT FÜR KANADA-STUDIEN vertreten durch Vorstand und Wissenschaftlichen Beirat Vorstand Prof. Dr. Caroline Rosenthal, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Institut für Anglistik/Amerikanistik, Lehrstuhl für Amerikanistik, Ernst-Abbe-Platz 8, 07743 Jena Prof. Dr. Kerstin Knopf, Universität Bremen, Fachbereich 10: Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften, Lehrstuhl für Postcolonial Literary and Cultural Studies, Bibliotheksstraße 1 / Gebäude GW 2, 28359 Bremen Prof. Dr. Bernhard Metz, Schatzmeister, Albrecht-Dürer-Str. 12, 79331 Teningen Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Sprache, Literatur und Kultur im anglophonen Kanada: Prof. Dr. Brigitte Johanna Glaser, Georg- August-Universität Göttingen, Seminar für Englische Philologie, Käte-Hamburger-Weg 3, 37073 Göttingen Sprache, Literatur und Kultur im frankophonen Kanada: Prof. Dr. Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink, Universität des Saarlandes, Fakultät 4 – Philosophische Fakultät II, Romanistik, Campus A4 -2, Zi. 2.12, 66123 Saarbrücken Frauen- und Geschlechterstudien: Prof. Dr. Jutta Ernst, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Ame- rikanistik, Fachbereich 06: Translations-, Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaft, An der Hochschule 2, 76726 Germersheim Geographie und Wirtschaftswissenschaften: Prof. Dr. Ludger Basten, Technische Universität Dort- mund, Fakultät 12: Erziehungswissenschaft und Soziologie, Institut für Soziologie, Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeographie, August-Schmidt-Str. 6, 44227 Dortmund Geschichtswissenschaften: Prof. Dr. Michael Wala, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Fakultät für Geschichts- wissenschaft, Historisches Institut, Universitätsstr. 150, 44780 Bochum Politikwissenschaft und Soziologie: Prof. Dr. Steffen Schneider, Universität Bremen, SFB 597 „Staat- lichkeit im Wandel”, Linzer Str. 9a, 28359 Bremen Indigenous and Cultural Studies: Dr. Michael Friedrichs, Wallgauer Weg 13 F, 86163 Augsburg Herausgeber Prof. -

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Annual Report 2009 DEAR SHAREHOLDERS

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Annual Report 2009 DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, Fiscal year 2009 proved to be a difficult time for • Expanded our presence in Asia, including the our industry and a challenging one for our company. planned release of NBA 2K Online; The economic environment influenced every facet of our sector. Unfavorable market conditions, as well • Completed a $138 million convertible note offering; as several changes in our product release schedule, • Resolved several significant historical legal matters; resulted in a net loss for fiscal year 2009 on net revenue of $968.5 million. • Signed a definitive asset purchase agreement to We remain confident in and committed to sell the Company’s non-core Jack of All Games our strategy of delivering a select portfolio of distribution business; and triple-A, top-rated titles across all key genres and expanding the reach and economic impact of our • Initiated a targeted restructuring of our corporate franchises through new distribution channels and departments to reduce costs and align our territories. Our industry-leading creative talent and resources with our goals. owned intellectual property, coupled with our sound financial position, provides us with the strength and OUR STRATEGY flexibility to build long-term value. Our strategy is to deliver efficiently a limited number of the most creative and innovative titles OUR ACCOMPLISHMENTS in our industry that capture mindshare and market We accomplished a great deal in the past year of share alike. Take-Two’s portfolio encompasses all of which we are very proud, including: today’s key genres, and we’re continually exploring new areas where we can leverage our development • Diversified our industry-leading product portfolio, expertise to expand our audiences across new which will be reflected in our products planned for territories, channels and distribution models. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Game Developers Conference Europe Wrap, New Women’S Group Forms, Licensed to Steal Super Genre Break Out, and More

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS SPEEDTREE RT 1.7 * SPACEPILOT OCTOBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>POSTMORTEM >>WALKING THE PLANK >>INNER PRODUCT ART & ARTIFICE IN DANIEL JAMES ON DEBUG? RELEASE? RESIDENT EVIL 4 CASUAL MMO GOLD LET’S DEVELOP! Thanks to our publishers for helping us create a new world of video games. GameTapTM and many of the video game industry’s leading publishers have joined together to create a new world where you can play hundreds of the greatest games right from your broadband-connected PC. It’s gaming freedom like never before. START PLAYING AT GAMETAP.COM TM & © 2005 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. A Time Warner Company. Patent Pending. All Rights Reserved. GTP1-05-116-104_mstrA_v2.indd 1 9/7/05 10:58:02 PM []CONTENTS OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 FEATURES 11 TOP 20 PUBLISHERS Who’s the top dog on the publishing block? Ranked by their revenues, the quality of the games they release, developer ratings, and other factors pertinent to serious professionals, our annual Top 20 list calls attention to the definitive movers and shakers in the publishing world. 11 By Tristan Donovan 21 INTERVIEW: A PIRATE’S LIFE What do pirates, cowboys, and massively multiplayer online games have in common? They all have Daniel James on their side. CEO of Three Rings, James’ mission has been to create an addictive MMO (or two) that has the pick-up-put- down rhythm of a casual game. In this interview, James discusses the barriers to distributing and charging for such 21 games, the beauty of the web, and the trouble with executables. -

Manual English.Pdf

Chapter 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS GETTING STARTED Chapter 1: Getting Started ...................................................................1 Operating Systems Chapter 2: Interactions & Classes ........................................................6 Chapter 3: School Supplies ...................................................................9 Windows XP Chapter 4: Bullworth Society .............................................................12 Windows Vista Chapter 5: Credits ..............................................................................16 Minimum System Requirements Memory: 1 GB RAM 4.7 GB of hard drive disc space Processor: Intel Pentium 4 (3+ GHZ) AMD Athlon 3000+ Video card: DirectX 9.0c Shader 3.0 supported Nvidia 6800 or 7300 or better ATI Radeon X1300 or better Sound card: DX9-compatible Installation You must have Administrator privileges to install and play Bully: Scholarship Edition. If you are unsure about how to achieve this, please consult your Windows system manual. Insert the Bully: Scholarship Edition DVD into your DVD-ROM Drive. If AutoPlay is enabled, the Launch Menu will appear otherwise use Explorer to browse the disc, and launch. ABOUT THIS BOOK Select the INSTALL option to run the installer. Since publishing the first edition there have been some exciting new Agree to the license Agreement. developments. This second edition has been updated to reflect those changes. You will also find some additional material has been added. Choose the install location: Entire chapters have been rewritten and some have simply been by default we use “C:\Program Files\Rockstar Games\Bully Scholarship deleted to streamline your learning experience. Enjoy! Edition” BULLY: SCHOLARSHIP EDITION CHAPTER 1: GETTING STARTED 1 Chapter 1 Installation continued CONTROLS Once Installation has finished, you will be returned to the Launch Menu. Controls: Standard If you do not have DirectX 9.0c installed on your PC, then we suggest Show Secondary Tasks Arrow Left launching DIRECTX INSTALL from the Launch Menu. -

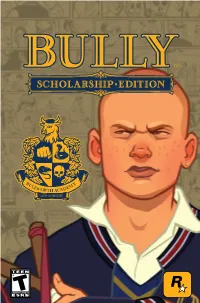

Rockstar Games Announces Bully: Scholarship Edition for the Xbox 360(TM) and Wii(TM)

Rockstar Games announces Bully: Scholarship Edition for the Xbox 360(TM) and Wii(TM) July 19, 2007 5:21 PM ET NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--July 19, 2007--Rockstar Games is proud to announce that Bully: Scholarship Edition is coming to the Xbox 360(TM) video game and entertainment system from Microsoft and the Wii(TM) home video game system from Nintendo this Winter. Both the Wii and Xbox 360 versions will retain the wit and deep gameplay of the previously released PlayStation(R)2 computer entertainment system title and will boast additional new content. Bully: Scholarship Edition takes place in the fictional New England boarding school of Bullworth Academy, and tells the story of 15-year-old Jimmy Hopkins as he experiences the highs and lows of adjusting to a new school. Capturing the hilarity and awkwardness of adolescence perfectly, Bully: Scholarship Edition pulls the player into its cinematic and engrossing world. Universally acclaimed upon first release, Bully: Scholarship Edition is a genre-crossing action game with a warmth and pathos that is unrivaled. Bully received a perfect "10/10" from Electronic Gaming Monthly and 1up.com and was heralded as "a great, well-crafted action game that has one of the best senses of humor around" by IGN.com. USA Today called it "a fantastic debut title by Rockstar Vancouver." The San Francisco Chronicle wrote "Bully has no shortage of creative energy, offering an immersive boarding school experience that is imaginative, funny and filled with surprises." Come and explore the zealous joy, mirth, and torment of youth with Jimmy Hopkins and Bully: Scholarship Edition when enrollment commences this Winter. -

Bullworth Society

WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox 360 Instruction TABLE OF CONTENTS Manual and any peripheral manuals for important safety and health information. Keep all manuals for future reference. For replacement manuals, see www.xbox. Chapter 1: Getting Started ...................................................................3 com/support or call Xbox Customer Support. Chapter 2: Interactions & Classes ........................................................5 Chapter 3: School Supplies ...................................................................8 Important Health Warning About Playing Video Games Chapter 4: Bullworth Society .............................................................11 Chapter 5: Credits ..............................................................................15 Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including fl ashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely than adults to experience these seizures. The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by taking the following precautions: Sit farther from the screen; use a smaller screen; play in a well-lit room; and do not play when you are drowsy or fatigued. If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. -

SANQUA Horizons N°6

SSANQUAANQUA hORIZONS Jeudi 1er février 2007 1 Hommage à Ben Récemment j’ai des envies de Tetris comme jamais. C’est la faute à Jika, je tiens à le signaler. C’est à cause de lui que je me suis remis à jouer à ce jeu débile avec le remake sur DS. Depuis, je ne quitte quasiment plus le mode online qui permet à tous de jouer, via wifi , contre d’autres glandeurs du monde entier. Il y a quelques jours, je me suis trouvé un concurrent du nom de «Ben», qui avait à peu près le même score que moi. Nous commençâmes à jouer et après mes premières victoires (3 à la suite) le voilà qui en redemande et me bat à plat de couture pour les 5 parties qui suivent. Vous imaginez la suite. Alors que je ne pensais qu’à une courte session de Tetris, me voilà encore debout, contre Ben, à deux heures du matin, à bout de batterie... au fi nal, Ben gagna au nombre de victoires (30 contre 27), mais je m’en tirais avec les honneurs au niveau des points. Ben, je ne sais pas qui tu es, gamin de cinq ans ou ado boutoneux, mais sache que tu m’as quand même bien pourri la soirée. Fait chier. Mais bravo quand même. 2 SSTARTAR Le légal, un vrai TTEAMEAM RREGALEGAL vacances. Nous remercions vacances. Nous remercions Ont participé à ce nouvel horizon : 1. SANQUA est le magazine au format PDF du site 5. Les propos diff usés dans Sanqua n’engagent bien Sanqualis.com. -

Playing Games: Creating the Neo-Liberal Person?

LARRY KUEHN Playing Games: Creating the Neo-liberal Person? The compelling attention to digital games that consumes so many is foreign to me. I feel as separate from that world as I do from any of the myriad of human cultures that I know by little more than their names. Yet I know that digital games have become a significant part of the economy, as well as to social and educational futures that do concern me a great deal. The estimated sales revenue of digital games in a recent year was $10 billion, more than the total intake from movies on a global basis. The latest release of Grand Theft Auto took in $500 million in the first week alone. Canadian companies that create these games are major producers, including Rockstar Games who created the Grand Theft Auto franchise. I’m not sure of why the world of games seems so inaccessible. However, the reality is that I would still much prefer to sit down with a novel than explore the game world. I can’t even get myself to try out the Sony Playstation attached to our TV set. Maybe the generational difference is a reality. Some would dismiss me as one of the “digital tourists,” as opposed to the “dig - ital natives,” the term rapidly becoming a cliché about young people who have grown up with the computer and the Internet as a part of their environment. These digital natives, according 55 OUR SCHOOLS/OUR SELVES to the claim, are so immersed in these media that they take to the games as just another part of the environment to engage for entertainment. -

Game Changers – Representations of Queerness in Canadian Videogame Design

R ENÉ R EINHOLD S CHALLEGGER Game Changers – Representations of Queerness in Canadian Videogame Design _____________________ Zusammenfassung Aufgrund der sich verändernden Demographie der Spielenden, sowie der Domestizie- rung und Entmystifizierung von Videospielen, ist das Medium in der Mitte der Gesell- schaft angekommen. Weite Teile des bisherigen Zielpublikums, die Gamer, reagieren aggressiv auf den resultierenden Autoritätsverlust und den wahrgenommenen Identi- tätsverlust. Besonders Darstellungen sexueller und geschlechtlicher Identitäten sind zu einem Schlachtfeld in diesem Kulturkrieg geworden, während sich die Industrie an ein kollabierendes imaginäres Publikum klammert. Zusammen mit einer Diversifizierung der Designer-Community müssen inklusive Repräsentationsregime über den Indie-Sek- tor hinaus zum Standard werden. BioWare hat mehr zu diesen notwendigen Verände- rungen beigetragen als irgendein anderes Studio. Mit Mass Effect und Dragon Age haben sie die Grenzen des Akzeptablen in der Darstellung von Geschlecht und Sexualität im Videospiel verschoben. Dragon Age: Inquisition (2014) ist das erste völlig inklusive Spiel der westlichen Designtradition, und es kommuniziert zudem noch zutiefst kanadi- sche Werte und Normen in seiner Identitätspolitik, seinem Repräsentationsregime und seiner sozio-politischen Ethik. Abstract Due to changing player demographics, the domestication, and demystification of vid- eogames, the medium has arrived in the middle of society. Large parts of the formerly privileged demographic, ‘The Gamers’, react aggressively to the resulting loss of authori- ty and a perceived loss of identity. Especially representations of sexual and gender iden- tities have become a battleground in these culture wars, with the industry still holding on to a collapsing imagined audience. Together with a diversification of the designer community, inclusive representational regimes must become the standard.