FAO-Report-Review-Of-Current-Share

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

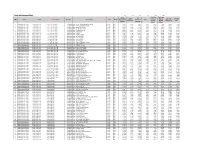

Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.No Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID

Details of Employees (Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID Women Medical 1 Dr. Afroze Khan Muhammad Chang (NULL) (NULL) Officer Women Medical 2 Dr. Shahnaz Abdullah Memon (NULL) 4130137928800 (NULL) Officer Muhammad Yaqoob Lund Women Medical 3 Dr. Saira Parveen (NULL) 4130379142244 (NULL) Baloch Officer Women Medical 4 Dr. Sharmeen Ashfaque Ashfaque Ahmed (NULL) 4140586538660 (NULL) Officer 5 Sameera Haider Ali Haider Jalbani Counselor (NULL) 4230152125668 214483656 Women Medical 6 Dr. Kanwal Gul Pirbho Mal Tarbani (NULL) 4320303150438 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 7 Dr. Saiqa Parveen Nizamuddin Khoso (NULL) 432068166602- (NULL) Officer Tertiary Care Manager 8 Faiz Ali Mangi Muhammad Achar (NULL) 4330213367251 214483652 /Medical Officer Women Medical 9 Dr. Kaneez Kalsoom Ghulam Hussain Dobal (NULL) 4410190742003 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 10 Dr. Sheeza Khan Muhammad Shahid Khan Pathan (NULL) 4420445717090 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 11 Dr. Rukhsana Khatoon Muhammad Alam Metlo (NULL) 4520492840334 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 12 Dr. Andleeb Liaqat Ali Arain (NULL) 454023016900 (NULL) Officer Badin S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID 1 MUHAMMAD SHAFI ABDULLAH WATER MAN unknown 1350353237435 10334485 2 IQBAL AHMED MEMON ALI MUHMMED MEMON Senior Medical Officer unknown 4110101265785 10337156 3 MENZOOR AHMED ABDUL REHAMN MEMON Medical Officer unknown 4110101388725 10337138 4 ALLAH BUX ABDUL KARIM Dispensor unknown -

Tando Muhammad Khan

Tando Muhammad Khan 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010002 GBPS - YAR M. KANDRA@PIR BUX KANDRA Primary Boys 9,117 1,823 7,294 1,823 1,823 7,294 29,175 7,294 2 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010016 GBPS - YAR MUHAMMAD KANDRA Primary Boys 11,323 2,265 9,058 2,265 2,265 9,058 36,233 9,058 3 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010017 GBPS - KHUDA BUX GUMB Primary Boys 14,353 2,871 11,482 2,871 2,871 11,482 45,929 11,482 4 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010022 GBPS - ALAM KHAN TALPUR Primary Boys 44,542 8,908 35,634 8,908 8,908 35,634 142,535 35,634 5 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010025 GBPS - PALIO GHUMRANI Primary Boys 28,220 5,644 22,576 5,644 5,644 22,576 90,303 22,576 6 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010026 GBPS - KARIMABAD Primary Boys 28,690 5,738 22,952 5,738 5,738 22,952 91,808 22,952 7 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. -

PESA-DP-Sukkur-Sindh.Pdf

Landsowne Bridge, Sukkur “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Sukkur September 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader development programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report. -

Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No

FINAL REPORT Mid-Term Evaluation /' " / " kku / Kondioro k I;sDDHH1 (Koo1,, * Nowbshoh On$ Hyderobcd Bulei Pt.ochi 7 godin Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No. 391-0480 Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development Islamabad, Pakistan IOC PDC-0249-1-00-0019-00 * Delivery Order No. 23 prepared by DE LEUWx CATHER INTERNATIONAL LIMITED May 26, 1993 Table of Contents Section Pafle Title Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables and Figures iv List of Abbieviations, Acronyms vi Basic Project Identification Data Sheet ix AID Evaluation Summary x Chapter 1 - Introduction 1-1 Chapter 2 - Background 2-1 Chapter 3 - Road Maintenance 3-1 Chapter 4 - Road Rehabilitation 4-1 Chapter 5 - Training Programs 5-1 Chapter 6 - District Revenue Sources 6-1 Appendices: - A. Work Plan for Mid-term Evaluation A-1 - B. Principal Officers Interviewed B-1 - C. Bibliography of Documents C-1 - D. Comparison of Resources and Outputs for Maintenance of District Roads in Sindh D-1 - E. Paved Road System Inventories: 6/89 & 4/93 E-1 - F. Cost Benefit Evaluations - Districts F-1 - ii Appendices (cont'd.): - G. "RRM" Road Rehabilitation Projects in SINDH PROVINCE: F.Y.'s 1989-90; 1991-92; 1992-93 G-1 - H. Proposed Training Schedule for Initial Phase of CCSC Contract (1989 - 1991) H-1 - 1. Maintenance Manual for District Roads in Sindh - (Revised) August 1992 I-1 - J. Model Maintenance Contract for District Roads in Sindh - August 1992 J-1 - K. Sindh Local Government and Rural Development Academy (SLGRDA) - Tandojam K-1 - L. -

Government of Sindh Finance Department

2021-22 Finance Department Government of Sindh 1 SC12102(102) GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 51,652,000 ______________ Total: 51,652,000 ______________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT ____________________________________________________________________________________________ BUILDINGS ____________________________________________________________________________________________ P./ADP DDO Functional-Cum-Object Classification & Budget NO. NO. Particular Of Scheme Estimates 2021 - 2022 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Rs 01 GENERAL PUBLIC SERVICE 011 EXECUTIVE & LEGISLATIVE ORGANS, FINANCAL 0111 EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE ORGANS 011103 PROVINCIAL EXECUTIVE KQ5003 SECRETARY (GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE) ADP No : 0733 KQ21221562 Constt. of Multi-storeyed Flats Phase-II at Sindh Governor's 51,652,000 House, Karachi (48 Nos.) including MT-s A12470 Others 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ Total Sub Sector BUILDINGS 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ TOTAL SECTOR GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ 2 SC12104(104) SERVICES GENERAL ADMIN & COORDINATION Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 1,432,976,000 ______________ Total: 1,432,976,000 ______________ _____________________________________________________________________________ -

National Assembly Polling Scheme

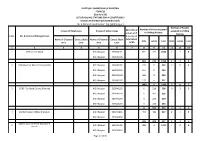

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN FORM 28 [See Rule 50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY Election to the National Assembly Sindh No. & Name of Constituency:- NA-208 Khairpur-I Number of Booths Number of Voters assigned In case of Rural areas In case of Urban Areas Serial No of assigned to Polling to Polling Stations voters on E Stations S.No. No. & Name of Polling Station A in case of Name of Electoral Census Block Name of Electoral Census Block bifurcation Male Female Total Male Female Total Area Code Area Code of EA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1 GPS Saleem Abad MC Khairpur 333040101 861 735 1596 2 2 4 MC Khairpur 333040106 861 735 1596 2 2 4 2 GPS Boys Faiz Abad Colony (Male) MC Khairpur 333040102 312 0 312 3 0 3 MC Khairpur 333040103 254 0 254 MC Khairpur 333040104 306 0 306 MC Khairpur 333040105 217 0 217 1089 0 1089 3 0 3 3 GGPS Faiz Abad Colony (Female) MC Khairpur 333040102 0 228 228 0 3 3 MC Khairpur 333040103 0 202 202 MC Khairpur 333040104 0 250 250 MC Khairpur 333040105 0 233 233 0 913 913 0 3 3 4 District Council Office Khairpur-I MC Khairpur 333040201 495 422 917 2 1 3 MC Khairpur 333040206 495 422 917 2 1 3 District Council Office Khairpur-II 5 MC Khairpur 333050405 1231 0 1231 4 0 4 (Male) MC Khairpur 333050410 Page 1 of 130 Number of Booths Number of Voters assigned In case of Rural areas In case of Urban Areas Serial No of assigned to Polling to Polling Stations voters on E Stations S.No. -

List of Candidates in Order of Merit Who Have Qualified Tests (Physical + Written + Interview)For the Post of Constable in Srp Against 1428 Vacancies

LIST OF CANDIDATES IN ORDER OF MERIT WHO HAVE QUALIFIED TESTS (PHYSICAL + WRITTEN + INTERVIEW)FOR THE POST OF CONSTABLE IN SRP AGAINST 1428 VACANCIES 1. Candidates who secured 40% and above out of 100 marks in written test were Interviewed for the purpose as per list provided by the Pakistan Testing Service. 2. Qualifying marks for Interview are 50% and above out of 50 marks. 3. The final result is the sum of total of the marks obtained in the written test and Interview as well as additional 15 marks given to the Interview Qualified candidates who are sons/daughters of retired / serving employees of Sindh Police having 25 years qualifying service as per Recruitment Policy. 4. The Candidates have been placed on merit list by giving priority as under : a. The candidates who got higher marks in total have been placed on top. b. If total marks are equal, the marks obtained in interview have been considered to place a candidate over to others who secured similar marks. c. If marks of interview are equal, the marks obtained in written test have been considered. d. If marks of written and interview are equal, the senior in age has been placed over. 5. Following is the list of Candidates who have qualified Physical, Written & Interview Tests for the Recruitment of Police Constable in SRP Sindh against 1428 vacancies. 6. The candidate merit list upto 1428 will be given medical letters for medical fitness against existing vacancy i.e. 1428 as was published in the advertisement of newspapers. They will be given offer letter of appointment after satisfactory completion of following codal formalities: a. -

2013-2014 Development Budget

1 SC22051(051) DEVELOPMENT (REVENUE) Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 33,098,087,000 ______________ Total: 33,098,087,000 ______________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT ____________________________________________________________________________________________ AGRICULTURE RESEARCH ____________________________________________________________________________________________ P./ADP DDO Functional-Cum-Object Classification & Budget NO. NO. Particular Of Scheme Estimates 2013 - 2014 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Rs 04 ECONOMIC AFFAIRS 042 AGRI,FOOD,IRRIGATION,FORESTRY & FISHING 0421 AGRICULTURE 042103 AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH & EXTENSION SERVIC HD9337 DIRECTOR GENERAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH SINDH. ADP No : 0001 HD09100137 Development and Promotion of Quality Seed through Public 134,896,000 Private Partnership in Sindh A03970 Others 134,896,000 TA9384 DY.DIRECTOR RICE RESEARCH STATION THATTA ADP No : 0002 TA12131410 Rehabilitation of Rice & Cotton Research Station Thatta 34,826,000 A03970 Others 34,826,000 KR9613 SECRETARY AGRICULTURE ADP No : 0003 HD12138010 Establishment of Agriculture Services Complex and Advisory 10,520,000 Centers in Sindh A03970 Others 10,520,000 HD9337 DIRECTOR GENERAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH SINDH. ADP No : 0004 KA11120007 Development of Bio - Pesticide for mangement of vegetable 9,414,000 pests. A03970 Others 9,414,000 LA9404 DIRECTOR QUAID-E-AWAM ARI LARKANA ADP No : 0005 LA11120008 -

Proceedings of Pakistan Congress of Zoology

PROCEEDINGS OF PAKISTAN CONGRESS OF ZOOLOGY Volume 34, 2014 All the papers in this Proceedings were refereed by experts in respective disciplines THIRTY FOURTH PAKISTAN CONGRESS OF ZOOLOGY held under auspices of THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF PAKISTAN at BAHAUDDIN ZAKARIYA UNIVERSITY, MULTAN FEBRUARY 25-27, 2014 CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Programme ii Members of the Congress x Citations Life Time Achievement Award 2014 Prof. Dr. Abdul Qadir Ansari ................................................ xix Prof. Dr. Muhammad Sharif Khan ........................................ xxi Prof. Dr. Agha Ikram Mohyuddin ........................................ xxii Zoologist of the year award 2014 .............................................. xxiv Prof. Dr. A.R. Shakoori Gold Medal 2014 ............................... xxvi Prof. Dr. Mirza Azhar Beg Gold Medal 2014 ......................... xxviii Prof. Imtiaz Ahmad Gold Medal 2014 ........................................ xxx Gold Medals for M.Sc. and Ph.D. positions 2014 .................... xxxii Research papers SAMI, A.J. AND SHAKOORI, A.R. Isolation of a growth hormone variant from pituitary of water buffalo Bubalus bubalis, identical to GH from SEI whale (Balaenoptera borealis) 1 MAHAR, M.A., WADAHAR, G.M., NAREJO, N.T. AND ABBASI, A.R. Biodiversity and fisheries potential of Lake Gahot, Matiary, Sindh, Pakistan 11 ULLAH, R., YAQUB, S., MUKHTAR, S., AHMED, M., RAFIQ, M., MEHMOOD, I., MEHFOOZ, M., Evaluation of ground water quality of Tehsil Barnala, District Bhimber, AJ&K, Pakistan 19 AYAZ, M.M., NAZIR, M.M., MURTAZA, S., AKHTAR, S., ZIA, W., KHAN,1 M.J., FAROOQ, A.A., ABDUL BASIT, A. AND NAEEM, M. Pseudomonas aeuroginosa and Streptococcus hemolyticum in the larva Przhevalskiana silenus (BRAUER), a uniqiue combination; fucultative or commensals 27 KHAN, A.A. Earthworms — The soil ecosystem engineers 31 Continued on page 356 [Abstracted and indexed in Biological Abstracts, Chemical Abstracts, Zoological Records, Informational Retrieval Limited, London, and Service Central De Documentation De L'ORSTOM, Paris. -

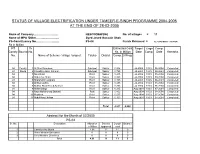

Status of Village Electrification Under Tameer-E-Sindh Programme 2004-2005 at the End of 28-02-2005

STATUS OF VILLAGE ELECTRIFICATION UNDER TAMEER-E-SINDH PROGRAMME 2004-2005 AT THE END OF 28-02-2005 Name of Company…………………….. HESCO(WAPDA) No. of villages = 11 Name of MPA /Other…………………… Syed Javed Hussain Shah PS-Constituency No……………………. PS-04 Funds Released = Rs. 4.960 Million ( 19-04-04) Rs in Million PS Sr. Estimated Cost Target %age Comp. Consty. Source No. Rs. in Million Date Comp. Date Remarks No. Name of Scheme / village / project Taluka District Comp. U/Prog. 04 Consty. 1 Ali Sher Shambani Salehpat Sukkur 0.804 Jul-2004 100% 06-2004 Completed 04 Quota 2 Choudhry Abdul Rehman Salehpat Sukkur 0.795 Jul-2004 100% 05-2004 Completed 04 3 Noorabad Rohri Sukkur 0.215 Jul-2004 100% 05-2004 Completed 04 4 Abdul Aziz Brohi Rohri Sukkur 0.363 Jul-2004 100% 09-2004 Completed 04 5 Sharafuddin Jagirani Rohri Sukkur 0.195 Jul-2004 100% 06-2004 Completed 04 6 Ali Bux Lodhro Rohri Sukkur 0.455 Jul-2004 100% 05-2004 Completed 04 7 Subhat Bhambhro & Kathore Rohri Sukkur 0.353 Jul-2004 100% 06-2004 Completed 04 8 Akbar Babgo Rohri Sukkur 0.315 Aug-2004 100% 07-2004 Completed 04 9 Raza Muhammad Shabani Rohi Sukkur 0.402 Aug-2004 100% 08-2004 Completed 04 10 Phuldreh Rohri Sukkur 0.537 Aug-2004 100% 07-2004 Completed 04 11 Abdul Haq Chohan Rohri Sukkur 0.103 Aug-2004 100% 07-2004 Completed Total 4.537 0.000 Abstract for the Month of 02/2005 PS-04 Sr. No. Description Allocation Schems Compl- Balance in Million Approved eted 1 Constituency Quota 4.96 11 11 0 2 Prime Minister Directives 0 0 0 0 3 Chief Minister Directives 0 0 0 0 Total 4.96 11 11 0 STATUS OF VILLAGE ELECTRIFICATION UNDER TAMEER-E-SINDH PROGRAMME 2004-2005 AT THE END OF 28-02-2005 Name of Company……………………. -

Karachi Range LIST of CANDIDATES SECURED 39 to 35 MARKS in NTS WRITTEN EXAMINATION

Karachi Range LIST OF CANDIDATES SECURED 39 TO 35 MARKS IN NTS WRITTEN EXAMINATION Sr # Name Father Name NIC Range 1 RAJESH RAMJEE RAMJEE 42201-5675679-5 Karachi 2 FAHAD WAKEEL WAKEEL AHMED QURESHI 42101-2072706-7 Karachi 3 ASAD MURTAZA GHULAM MURTAZA 42301-2323278-5 Karachi 6 ALI ARSHAD KHAN ABDUL QUYYUM 42301-0992176-7 Karachi 7 SHAHID RASOOL MUHAMMAD RASOOL 42401-3564904-1 Karachi 8 SUMAIR ARSHID HUSSAIN 42000-8249827-1 Karachi 9 HASSAN SHAH GULEEM SHAH 42501-6928198-5 Karachi 10 IZHAR AHMAD ABDUL RAZZAQ 42301-5735123-9 Karachi 11 MUHAMMAD AFTAB MUSHTAQ AHMAD 42501-4708294-5 Karachi 12 AAMIR SHEHZAD MUHAMMAD ARSHAD 42401-4713553-3 Karachi 13 SHERYAR ARHSAD 11111-1111111-1 Karachi 14 SAMI ULLAH MUHAMMAD KARIM 42501-9539217-9 Karachi 15 SOHAIL NAWAZ MUHAMMAD RAHEEM NAWAZ 42301-8778349-5 Karachi 16 DANISH BUTT MUHAMMAD BOTA 4 42401-5000106-7 Karachi 17 MUHAMMAD PARVEZ GUL MUHAMMAD 42501-2580075-1 Karachi 18 AMJAD ALI MUHAMMAD RAMZAN 42501-6243951-3 Karachi 19 UMAR HAYAT KHAN SYED UR REHMAN 42101-8289442-1 Karachi 20 RANA MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD RANA MUHAMMAD SARWAR 42201-8274744-7 Karachi 21 NAWAB KHAN ABDUL MALIK KHAN 42401-1139863-5 Karachi 22 MUHAMMAD MUJEEB SULEMAN SHER 42501-2082134-9 Karachi 23 ADNAN KHAN SHER MOHAMMAD KHAN 42501-5962280-9 Karachi 24 NADEEM ALI SOLANGI MUHAMMAD SAFFAR 41203-4952336-3 Karachi 25 NAZIR ALI WAZIR ALI 45204-2026568-9 Karachi 26 AKRAM DIN SANASI 42501-7374502-5 Karachi Page 1 of 3 Karachi Range LIST OF CANDIDATES SECURED 39 TO 35 MARKS IN NTS WRITTEN EXAMINATION Sr # Name Father Name NIC Range 27 KHYAL UMER -

Tehsil UC/Taluka Village/Mohallah 1 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando

Litreacy Center Address Centers' Date No. of Province District CNIC No. of Center Timing Learners Teacher's Name Sr. # Tehsil UC/Taluka Village/Mohallah Establishment enrolled 1 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Khuda Bux Bakari Shamim 4110467164908 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 23 2 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Lakha Dino Mallah Nosheen 4110478968200 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 3 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Azadar Hussain Tilat Farwah 411046534546 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 4 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Vikio Mallah Zahida 45881235042 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 5 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Muhammad Qasim Mallah Fareeda 4110454658382 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 6 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Muhammad Juman Mallah Farha Naz 4110402505244 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 7 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Mir Kazafi Ashya 4120180504304 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 8 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Muhammad Soomar Mallah Iqra 4110441520324 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 9 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Jalil Utho Nasreen 4110416284930 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 10 Sindh Badin Tando Bago Tando Bago Yousif Mallah Shaila 4110475899842 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 11 Sindh Badin Badin Kadhan Bilawal Mallah Shahida 4110184250330 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 12 Sindh Badin Badin Kadhan Ali Muhmmad Mallah Gulshan 4110164241104 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 20 13 Sindh Badin Badin Kadhan Pandhi Ghirano Naseema 4110150715166 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 14 Sindh Badin Badin Kadhan H.Abdullah Ghirano Najma 4110160973190 1/1/2020 2:00 to 5:00 25 15 Sindh Badin Badin Kadhan