Arthurian Mythology in the Twentieth Century: T.H. White and John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantasy & Science Fiction

Alphabetical list of Authors Clonmel Library Douglas Adams Kazuo Ishiguro Clonmel Library Issac Asimov PD James Ray Bradbury Robert Jordan Terry Brooks Kate Jacoby RecommendedRecommended Trudi Canavan Ursala K. Le Guin Arthur C Clarke George Orwell Susanna Clarke Anne McCaffery ReadingReading Philip K. Dick George RR Martin David Eddings Mervyn Peake Raymond E. Feist Terry Pratchett American Gods Philip Pullman Neil Gaiman Brandon Sanderson David Gemmell JRR Tolkein Terry Goodkind Jules Verne Robert A. HeinLein Kurt Vonnegut FantasyFantasy && Frank Herbert T.H. White Robin Hobb Aldous Huxley Clonmel Library ScienceScience FictionFiction Opening Hours & Contact Details Monday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Tuesday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Wednesday: 9.30 am – 8.00 pm Thursday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Friday: 9.30 am – 1pm & 2pm - 5pm Saturday: 10.00 am – 1pm & 2pm-5pm Phone: (052) 6124545 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.tipperarylibraries.ie/clonmel 11 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea AnAn IntroductionIntroduction Jules Verne First published 1869 toto FantasyFantasy French naturalist Dr. Aronnax embarks on an expedition to hunt down a sea monster, only to discover instead the && ScienceScience FictionFiction Nautilus, a remarkable submarine built by the enigmatic Captain Nemo. Together Nemo and Aronnax explore the antasy is a genre that uses magic and other supernatural forms underwater marvels, undergo a transcendent experience as a primary element of plot, theme, and/or setting. Fantasy is amongst the ruins of Atlantis, and plant a -

(1913). Tome II

Notes du mont Royal www.notesdumontroyal.com 쐰 Cette œuvre est hébergée sur « No- tes du mont Royal » dans le cadre d’un exposé gratuit sur la littérature. SOURCE DES IMAGES Canadiana LES MABINOGION LES Mabinogion du Livre Rouge de HERGEST avec les variantes du Livre Blanc de RHYDDERCH Traduits du gallois avec une introduction, un commentaire explicatif et des notes critiques FA R J. LOTH PROFESSEUR Ali COLLÈGE DE FRANCE ÉDITION ENTIÈREMENT REVUE, CORRXGÉE ET AUGMENTÉE FONTEMOING ET Cie, ÉDITEURS PARIS4, RUE LE son, 4 1913 . x 294-? i3 G 02; f! LES MABINOGION OWEIN (1’ ET LUNET i2) ou la Dame de la Fontaine L’empereur Arthur se trouvait à Kaer Llion (3)sur W’ysc. Or un jour il était assis dans sa chambre en. (1) Owen ab Urycn est un des trois gingndqyrn (rois bénis) de l’île (Triades Mab., p. 300, 7). Son barde, Degynelw, est un des trois gwaewrudd ou hommes à la lance rouge (Ibid., p. 306, 8 ; d’autres triades appellent ce barde Tristvardd (Skene. Il, p. 458). Son cheval, Carnavlawc, est un des trois anreilhvarch ou che- vaux de butin (Livre Noir, Skene,ll, p. 10, 2). Sa tombe est à Llan Morvael (Ibid., p. 29, 25 ; cf. ibid, p. 26, 6 ; 49, 29, 23). Suivant Taliesin, Owein aurait tué Ida Flamddwyn ou Ida Porte-brandon, qui paraît être le roi de Northumbrie, dont la chronique anglo- saxonne fixe la mort à l’année 560(Petrie, Mon. hist. brit., Taliesin, Skene, Il, p. 199, XLIV). Son père, Uryen, est encore plus célè- bre. -

Date Night a King Arthurs Short Story by K. M. Shea

Date Night A King Arthurs Short Story by K. M. Shea Britt didn’t know what to expect when Merlin said he would pick her up for their date that night—their first date ever, really. It had crossed her mind that he could arrive in a horse- drawn carriage, a Mercedes-Benz, or anything in between. So she was somewhat surprised when he pulled up on the street in front of her apartment complex in a silver Toyota SUV. It was a nice car. It still sported the new car smell, and it had a leather interior and heated seats. But it was surprisingly...practical. “So you really have a driver’s license?” Britt asked as she buckled her seatbelt. “Indeed,” Merlin said. He waited until she was situated before shifting the car into drive. “All of us are certified citizens of the United States. We all pay taxes, and we all have our driver’s license. Well, excluding Morgan, that is. She keeps failing her driver’s test, but that’s because she drives like a maniac.” “How did you manage to get IDs?” Britt asked. “The Lady of the Lake,” Merlin said. “A number of her handmaidens work for the US government. “I don’t know if that’s reassuring or terrifying,” Britt said. Merlin made a turn, navigating through the maze of city streets. “Oh, the US is not the only pie she has her thumb in. Most of her power lays in her real estate holdings and in the great number of favors the various faerie royalty throughout the world owe her.” “I’m starting to think she would’ve made a wonderful High King of Britain,” Britt said. -

Language in the Modern Arthurian Novel

Volume 20 Number 4 Article 4 Winter 1-15-1995 Whose English?: Language in the Modern Arthurian Novel Lisa Padol Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Padol, Lisa (1995) "Whose English?: Language in the Modern Arthurian Novel," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 20 : No. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol20/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Analyzes the use of language, mood/tone, vocabulary, syntax, idioms, metaphors, and ideas in a number of contemporary Arthurian novels. Additional Keywords Arthurian myth; Arthurian myth in literature; Language in literature; Style in literature This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Arthurian Legend Is the Round Table, a Symbol of the Civic Ideals of Knighthood and the Way Arthur Governs His Realm

Narrative English 338: Literature and Life—The Legend of King Arthur The course introduces students to three of the best and most popular modern adaptations of the King Arthur legend. This material is well suited to the goals of the Foundational Studies Program, and Literary Studies. Assignments and activities provide students with varied modalities for demonstrating their achievement. Bolded text and footnotes in the annotated syllabus provide detailed information. This narrative explains specific aspects of the novels that are most relevant to the goals. Aesthetic responsiveness and interpretive ability. Though they all use multiple modes of irony and incorporate elements of fantasy (transformation and time travel) the assigned novels (and their movie adaptations) belong to different genres and so elicit different responses and interpretive moves: Once and Future King is part comic coming-of-age-story told through fable, and part tragedy of adult experience. Mists of Avalon is a complexly plotted multi-generational saga grounded in Celtic myth. Connecticut Yankee is a bitter satire (though in the movie version transformed to musical comedy). Connect writings to their literary, cultural, and historical contexts. Written in different eras, the novels explore issues and events of their time in the guise of another historical context, the Middle Ages. The multiple contexts of the same story make a rich subject for teaching, not only enhancing students’ knowledge of the contexts, but also showing them how to read contextually and the importance of context for understanding literary works (and by extension, other documents and artifacts). Analyze issues to answer questions about human experience, systems, and environment. -

The Matter of Britain

THE MATTER OF BRITAIN: KING ARTHUR'S BATTLES I had rather myself be the historian of the Britons than nobody, although so many are to be found who might much more satisfactorily discharge the labour thus imposed on me; I humbly entreat my readers, whose ears I may offend by the inelegance of my words, that they will fulfil the wish of my seniors, and grant me the easy task of listening with candour to my history May, therefore, candour be shown where the inelegance of my words is insufficient, and may the truth of this history, which my rustic tongue has ventured, as a kind of plough, to trace out in furrows, lose none of its influence from that cause, in the ears of my hearers. For it is better to drink a wholesome draught of truth from a humble vessel, than poison mixed with honey from a golden goblet Nennius CONTENTS Chapter Introduction 1 The Kinship of the King 2 Arthur’s Battles 3 The River Glein 4 The River Dubglas 5 Bassas 6 Guinnion 7 Caledonian Wood 8 Loch Lomond 9 Portrush 10 Cwm Kerwyn 11 Caer Legion 12 Tribuit 13 Mount Agned 14 Mount Badon 15 Camlann Epilogue Appendices A Uther Pendragon B Arthwys, King of the Pennines C Arthur’s Pilgrimages D King Arthur’s Bones INTRODUCTION Cupbearer, fill these eager mead-horns, for I have a song to sing. Let us plunge helmet first into the Dark Ages, as the candle of Roman civilisation goes out over Europe, as an empire finally fell. The Britons, placid citizens after centuries of the Pax Romana, are suddenly assaulted on three sides; from the west the Irish, from the north the Picts & from across the North Sea the Anglo-Saxons. -

The Aeneid with Rabbits

The Aeneid with Rabbits: Children's Fantasy as Modern Epic by Hannah Parry A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks are owed to Geoff Miles and Harry Ricketts, for their insightful supervision of this thesis. Thanks to Geoff also for his previous supervision of my MA thesis and of the 489 Research Paper which began my academic interest in tracking modern fantasy back to classical epic. He must be thoroughly sick of reading drafts of my writing by now, but has never once showed it, and has always been helpful, enthusiastic and kind. For talking to me about Tolkien, Old English and Old Norse, lending me a whole box of books, and inviting me to spend countless Wednesday evenings at their house with the Norse Reading Group, I would like to thank Christine Franzen and Robert Easting. I'd also like to thank the English department staff and postgraduates of Victoria University of Wellington, for their interest and support throughout, and for being some of the nicest people it has been my privilege to meet. Victoria University of Wellington provided financial support for this thesis through the Victoria University Doctoral Scholarship, for which I am very grateful. For access to letters, notebooks and manuscripts pertaining to Rosemary Sutcliff, Philip Pullman, and C.S. Lewis, I would like to thank the Seven Stories National Centre for Children's Books in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Oxford University. Finally, thanks to my parents, William and Lynette Parry, for fostering my love of books, and to my sister, Sarah Parry, for her patience, intelligence, insight, and many terrific conversations about all things literary and fantastical. -

The Early Arthur: History and Myth

1 RONALD HUTTON The early Arthur: history and myth For anybody concerned with the origins of the Arthurian legend, one literary work should represent the point of embarkation: the Historia Brittonum or History of the British . It is both the earliest clearly dated text to refer to Arthur, and the one upon which most efforts to locate and identify a histor- ical fi gure behind the name have been based. From it, three different routes of enquiry proceed, which may be characterised as the textual, the folkloric and the archaeological, and each of these will now be followed in turn. The Arthur of literature Any pursuit of Arthur through written texts needs to begin with the Historia itself; and thanks primarily to the researches of David Dumville and Nicholas Higham, we now know more or less exactly when and why it was produced in its present form. It was completed in Gwynedd, the north-western king- dom of Wales, at the behest of its monarch, Merfyn, during the year 830. Merfyn was no ordinary Welsh ruler of the age, but an able and ruthless newcomer, an adventurer who had just planted himself and his dynasty on the throne of Gwynedd, and had ambitions to lead all the Welsh. As such, he sponsored something that nobody had apparently written before: a com- plete history of the Welsh people. To suit Merfyn’s ambitions for them, and for himself, it represented the Welsh as the natural and rightful owners of all Britain: pious, warlike and gallant folk who had lost control of most of their land to the invading English, because of a mixture of treachery and overwhelming numbers on the part of the invaders. -

A Study of the Genre of T. H. White's Arthurian Books a Thesis

A Study of the Genre of T. H. White's Arthurian Books A Thesis for the Degree of Ph. D from the University of Wales Susan Elizabeth Chapman June 1988 Summary T. H. White's Arthurian books have been consistently popular with the general public, but have received limited critical attention. It is possible that such critical neglect is caused by the books' failure to conform to the generic norms of the mainstream novel, the dominant form of prose fiction in the twentieth century. This thesis explores the way in which various genres combine in The. Once alai Future King.. Genre theory, as developed by Northrop Frye and Alastair Fowler, is the basis of the study. Neither theory is applied fully, but Frye's and Fowler's ideas about the function of genre as an interpretive tool underpin the study. The genre study proper begins with an examination of the generic repertoire of the mainstream novel. A study of The. Qnce gknj Future King in relation to this form reveals that it exhibits some of its features, notably characterization and narrative, but that it conspicuously lacks the kind of setting typical of the mainstream novel. A similar approach is followed with other subgenres of prose fiction: the historical novel; romance; fantasy; utopia. In each case Thy Once angj Future King is found to exhibit some key features, unique to that form, although without sufficient of its characteristics to be described fully in those terms. The function of the comic and tragic modes within The. Qnce änd Future King is also considered. -

THE MANY FACES of MERLIN in MODERN FICTION Author(S): Christopher Dean Source: Arthurian Interpretations, Vol

THE MANY FACES OF MERLIN IN MODERN FICTION Author(s): Christopher Dean Source: Arthurian Interpretations, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Fall 1988), pp. 61-78 Published by: Scriptorium Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27868651 . Accessed: 09/06/2014 19:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Scriptorium Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Arthurian Interpretations. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.212.18.200 on Mon, 9 Jun 2014 19:11:41 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MANY FACES OF MERLIN IN MODERN FICTION1 Merlin, Arthur's enchanter and prophet, a figure ofmystery, ofmagic, and of awesome power, is a name that has been part of our literature formore than eight centuries. But the same creature is never conjured, for, as Jane Yolen says, was he not "a shape-shifter, a man of shadows, a son of an incubus, a creature of the mists" (xii)? Or, to quote Nikolai Tolstoy, as a "trickster, illusionist, philosopher and sorcerer, he represents an archetype to which the race turns for guidance and protection" (20). -

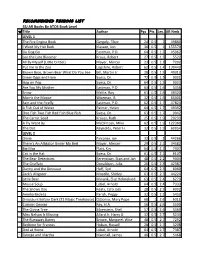

RECOMMENDED READING LIST SSJ AR Books by ATOS Book Level ✔️Title Author Pgs Pts Lev

RECOMMENDED READING LIST SSJ AR Books By ATOS Book Level ✔️Title Author Pgs Pts Lev. AR Nmb LEVEL 1 The Fire Engine Book Gergely, Tibor 24 0.5 1 49860 I Want My Hat Back Klassen, Jon 36 0.5 1 155570 Go Dog Go Eastman, P.D. 64 0.5 1.2 45962 Leo the Late Bloomer Kraus, Robert 27 0.5 1.2 5522 All By Myself (Little Critter) Mayer, Mercer 23 0.5 1.3 7202 Put me in the Zoo Lopshire, Robert 62 0.5 1.4 130449 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See Bill, Martin Jr. 28 0.5 1.5 40313 Green Eggs and Ham Suess, Dr. 72 0.5 1.5 9021 Hop on Pop Suess, Dr. 64 0.5 1.5 9023 Are You My Mother Eastman, P.D. 63 0.5 1.6 5456 Snow McKie, Roy 61 0.5 1.6 49420 Morris the Moose Wiseman, B. 32 0.5 1.6 65001 Sam and the Firefly Eastman, P.D. 62 0.5 1.7 47824 A Fish Out of Water Palmer, Helen 64 0.5 1.7 49392 One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish Suess, Dr. 63 0.5 1.7 9042 The Carrot Seed Krauss, Ruth 25 0.5 1.9 29233 A Fly Went By McClintock, Mike 62 0.5 1.9 122360 The Dot Reynolds, Peter H. 32 0.5 1.9 69954 LEVEL 2 Olivia Falconer, ian 32 0.5 2 44266 There's An Alligator Under My Bed Mayer, Mercer 29 0.5 2.1 34582 Big Max Platt, Kin 64 0.5 2.1 7307 Cat in the Hat Suess, Dr. -

The Once and Future King the Once and Future King

Prestwick House AP Literature SampleTeaching Unit™ Prestwick House Prestwick House * * AP Literature AP Literature Teaching Unit Teaching Unit * AP is a registered trademark of The College Board, * AP is a registered trademark of The College Board, which neither sponsors or endorses this product. which neither sponsors or endorses this product. AT.H. White’s P AT.H. White’s P The Once and Future King The Once and Future King Click here A P RESTWICK H OUSE P UBLIC A TION A P RESTWICK H OUSE P UBLIC A TION Item No. 309061 to learn more about this Teaching Unit! Click here to find more Classroom Resources for this title! More from Prestwick House Literature Grammar and Writing Vocabulary Reading Literary Touchstone Classics College and Career Readiness: Writing Vocabulary Power Plus Reading Informational Texts Literature Teaching Units Grammar for Writing Vocabulary from Latin and Greek Roots Reading Literature Advanced Placement in English Literature and Composition Individual Learning Packet Teaching Unit The Once and Future King by T. H. White written by Jill Clare Item No. 309061 The Once and Future King ADVANCED PLACEMENT LITERATURE TEACHING UNIT The Once and Future King Objectives By the end of this Unit, the student will be able to: 1. explain the elements of tragedy and explain how the text can be regarded as a tragedy. 2. analyze the text for evidence of foreshadowing and explain how foreshadowing contributes to the tone of the work. 3. analyze the text for thematic development and explain how specific themes contribute to the overall meaning of the text.