Exploring the Role of Police Misconduct Within Canadian Wrongful Conviction Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Innocence Revolution and Proposals to Modify the American Criminal Trial

Texas A&M Law Review Volume 3 Issue 2 2015 Reinventing the Trial: The Innocence Revolution and Proposals to Modify the American Criminal Trial Marvin Zalman Ralph Grunewald Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Marvin Zalman & Ralph Grunewald, Reinventing the Trial: The Innocence Revolution and Proposals to Modify the American Criminal Trial, 3 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 189 (2015). Available at: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V3.I2.2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Texas A&M Law Review by an authorized editor of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REINVENTING THE TRIAL: THE INNOCENCE REVOLUTION AND PROPOSALS TO MODIFY THE AMERICAN CRIMINAL TRIAL* By: Marvin Zalman** and Ralph Grunewald*** ABSTRACT Law review articles by D. Michael Risinger, Tim Bakken, Keith Findley, Samuel Gross, and Christopher Slobogin have proposed modifications to pre- trial and trial procedures designed to reduce wrongful convictions. Some fit within the adversary model and others have “inquisitorial” features. We com- pare and evaluate the recommendations from the perspectives of lawyer-schol- ars trained in the United States and Germany. We examine the proposals for their novelty, feasibility, complexity, likely impact, and possible negative or positive side effects. This Article describes, compares, and critically analyzes the articles; suggests additional truth-enhancing procedural reforms; and pro- vides a platform for further analysis. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

Scanned Image

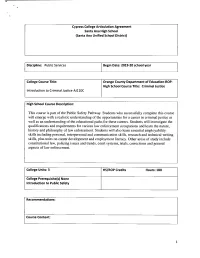

Cypress College Articulation Agreement Santa Ana High School (Santa Ana Unified School District) Discipline: Public Services Begin Date: 2019-20 school year College Course Title: Orange County Department of Education-ROP- High School Course Title: Criminal Justice Introduction to Criminal Justice-AJ110C High School Course Description: This course is part of the Public Safety Pathway. Students who successfully complete this course will emerge with a realistic understanding of the opportunities for a career in criminal justice as well as an understanding of the educational paths for these careers. Students will investigate the qualifications and requirements for various law enforcement occupations and learn the nature, history and philosophy of law enforcement. Students will also learn essential employability skills including personal, interpersonal and communication skills, research and technical writing skills, plus units on career development and employment literacy. Other areas of study include constitutional law, policing issues and trends, court systems, trials, corrections and general aspects of law enforcement. College Units: 3 HS/ROP Credits Hours: 180 College Prerequisite(s) None Introduction to Public Safety Recommendations: Course Content: > . INDUSTRY FOCUS PR law . Identify possible career profiles and pathways in enforcement. Describe current labor market projections. WH . Use law enforcement industry terminology. DP observe . Explain occupational safety issues and all safety rules. Develop perspective and understanding of all aspects of the law enforcement industry. NOU and become police . Identify the educational physical requirements needed to a officer. Explain the process of background checks for eligibility, and the implications of prior convictions and personal history. 8. Review criminal justice training and educational programs @ . CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM . -

Voices of Forensic Science

Chapter 3 The Contamination and Misuse of DNA Evidence Vanessa Toncic, Alexandra Silva "Genes are like the story, and DNA is the language that the story is written in." (Kean, 2012) To understand how potentially mishandled or contaminated DNA evidence could be manipulated or presented in court, (under false pretenses), as an evidentiary ‘gold standard,’ it is important to first explain why, and under what circumstances, DNA evidence is in fact a gold standard. DNA evidence may be disguised as a gold standard when either the techniques used, or the representation of the data has been skewed and is no longer reflective of DNA as a gold standard. This chapter will explore the use of mixed DNA profiles as well as low copy number (LCN) techniques of DNA analysis, and how these methods may not be deserving of the ‘gold standard’ seal associated with DNA evidence. We will explore the biological aspect of issues with these methods and how they may reflect a contaminated DNA sample. Notably, DNA evidence that has been appropriately collected and analyzed may still be purposely misrepresented to a judge and/or jury. DNA as an evidentiary gold standard requires proper handling from the onset of collection, throughout analysis and storage, as well as during presentation in court to ensure that the quality of evidence is upheld. DNA evidence and its associated challenges are multi-faceted areas of study. These studies include issues surrounding the collection as well as the analysis of evidence leading to subsequent contamination and root cause analysis. There also exists debate on the ethics and privatization of DNA given the popularization of online DNA databases. -

BSCHIFFER 2009 05 28 These

UNIVERSITY OF LAUSANNE FACULTY OF LAW AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE SCHOOL OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE FORENSIC SCIENCE INSTITUTE The Relationship between Forensic Science and Judicial Error: A Study Covering Error Sources, Bias, and Remedies PhD thesis submitted to obtain the doctoral degree in forensic science Beatrice SCHIFFER Lausanne, 2009 To my family, especially my parents Summary Forensic science - both as a source of and as a remedy for error potentially leading to judicial error - has been studied empirically in this research. A comprehensive literature review, experimental tests on the influence of observational biases in fingermark comparison, and semi- structured interviews with heads of forensic science laboratories/units in Switzerland and abroad were the tools used. For the literature review , some of the areas studied are: the quality of forensic science work in general, the complex interaction between science and law, and specific propositions as to error sources not directly related to the interaction between law and science. A list of potential error sources all the way from the crime scene to the writing of the report has been established as well. For the empirical tests , the ACE-V (Analysis, Comparison, Evaluation, and Verification) process of fingermark comparison was selected as an area of special interest for the study of observational biases, due to its heavy reliance on visual observation and recent cases of misidentifications. Results of the tests performed with forensic science students tend to show that decision-making stages are the most vulnerable to stimuli inducing observational biases. For the semi-structured interviews, eleven senior forensic scientists answered questions on several subjects, for example on potential and existing error sources in their work, of the limitations of what can be done with forensic science, and of the possibilities and tools to minimise errors. -

Trial by Media ( Female )

Trial-by-Media Trial-by-Media Table Of Contents About .............................................................. 3 Amanda Knox ........................................................ 4 Analysis of Women executed in United States since 1976 ........................... 5 Ann Rule ............................................................ 8 Arguments against death penalty ........................................... 9 Arizona-perverts ..................................................... 11 Ashley Smith ......................................................... 12 Bad Lawyering ....................................................... 13 Baddies ............................................................. 17 Bradley Cooper ....................................................... 19 Break the chain ....................................................... 20 Carlos DeLuna ....................................................... 21 Case Rating .......................................................... 22 Cases by Country or State ................................................ 23 Claudine Longet ...................................................... 26 Cold Case ........................................................... 27 Congress Release Project ................................................ 28 Craigavon Two ....................................................... 29 Darlie Routier ........................................................ 30 David Camm ......................................................... 31 Debra Milke ........................................................ -

Miller Thomson LLP 1998-2008 WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS in CANADA

Robson Court MILLER 1000-840 Howe Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6Z 2M1 THOMSON LLP Tel. 604.687.2242 Barristers & Solicitors Fax. 604.643.1200 Patent & Trade-Mark Agents www.millerthomson.com VANCOUVER TORONTO CALGARY EDMONTON LONDON KITCHENER-WATERLOO GUELPH MARKHAM MONTRÉAL Wrongful Convictions in Canada Robin Bajer, Monique Trépanier, Elizabeth Campbell, Doug LePard, Nicola Mahaffy, Julie Robinson, Dwight Stewart International Conference of the International Society for the Reform of Criminal Law June 2007 This article is provided as an information service only and is not meant as legal advice. Readers are cautioned not to act on the information provided without seeking specific legal advice with respect to their unique circumstances. © Miller Thomson LLP 1998-2008 WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS IN CANADA Authors: Robin Bajer Monique Trépanier Elizabeth Campbell Doug LePard Nicola Mahaffy Julie Robinson Dwight Stewart TABLE OF CONTENTS WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS IN CANADA ...............................................................................2 CHAPTER ONE – Introduction and Background By Robin Bajer and Monique Trépanier..................................................................2 CHAPTER TWO – How Police Departments Can Reduce the Risk of Wrongful Convictions By Elizabeth Campbell and Doug LePard.............................................................12 CHAPTER THREE – Review: Wrongful Convictions and the Role of Crown Counsel By Nicola Mahaffy and Julie Robinson.................................................................40 -

Voices of Forensic Science

Chapter 14 The Harmful Repercussions of Wrongful Convictions Preetha Jayanthan, Bailey Hennessy "No one should ever be wrongfully deprived of their rights to liberty and freedom without just cause, yet in the past 25 years alone thousands of people have been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to tens of thousands of years in prison." (Kerik, B. B., 2015) Wrongful convictions occur when the criminal justice system fails to uphold its gold standards and thus miscarriages of justice occur. This chapter will take a close look into wrongful convictions caused by, improperly implementing the gold standards of forensic science through examining the aftermath of a wrongful conviction. By paying particular attention to the process of exonerating an individual; with an emphasis on the resources, or lack thereof, available. The chapter will then move towards the supposed ‘finish line’ of being exonerated. This decision, however, does not make up for the psychological trauma caused to the victim of a wrongful conviction. For many, an incorrect conviction can cost years, if not decades, of one’s life. This often causes wrongfully convicted individuals to lose friends, family, and other important relationships, ultimately resulting in mental health issues. What is a Wrongful Conviction? A wrongful conviction occurs when an individual is accused or sentenced for a crime they did not commit, in other words, a miscarriage of justice has occurred (Denov & Campbell, 2005). The root causes of wrongful convictions are seen to be both individual and systemic in nature (Denov & Campbell, 2005). Some examples 253 Are We There Yet? The Golden Standards of Forensic Science of root causes include false confessions, and bias in the system, such as tunnel vision (Denov & Campbell, 2005). -

NCSBI Evidence Guide Issue Date: 01/01/2010 Page 1 of 75 ______

NCSBI Evidence Guide Issue Date: 01/01/2010 Page 1 of 75 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation EVIDENCE GUIDE North Carolina Department of Justice Attorney General Roy Cooper North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation Director Robin P. Pendergraft Crime Laboratory Division Assistant Director Jerry Richardson January 2010 NCSBI Evidence Guide Issue Date: 01/01/2010 Page 2 of 75 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address questions regarding this guide to the: North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation Evidence Control Unit 121 East Tryon Road Raleigh, North Carolina 27603 phone: (919) 662-4500 (Ex. 1501) or Fax questions or comments to the: North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation Evidence Control Unit at fax: (919) 661-5849 This guide may be duplicated and distributed to any law enforcement officer whose duties include the collection, preservation, and submission of evidence to the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation Crime Laboratory Division. NCSBI Evidence Guide Issue Date: 01/01/2010 Page 3 of 75 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents SPECIAL NOTICES .............................................................................................................. Page 4 Where to Submit Evidence .................................................................................................... -

Rule of Law Report

RULE OF LAW REPORT ISSUE 2 JUNE 2018 EDITOR’S NOTE Heather MacIvor 2 TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF ADVOCACY FOR THE WRONGLY CONVICTED Win Wahrer 3 LEVEL – CHANGING LIVES THROUGH LAW Heather MacIvor 6 EDITOR’S NOTE This issue features two leading Canadian organizations dedicated to justice and the rule of law. Innocence Canada, formerly called AIDWYC (Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted), is dedicated to preventing and correcting miscarriages of justice. Win Wahrer Heather MacIvor has been with Innocence Canada since LexisNexis Canada the beginning. As the organization celebrates its 25th anniversary, Win tells its story. She also spotlights some of the remarkable individuals who support Innocence Canada, and those Photo by Fardeen Firoze whom it has supported in their struggles. Level, formerly Canadian Lawyers Abroad, targets barriers to justice. It aims to educate and empower Indigenous youth, enhance cultural competency in the bench and Bar, and mentor future leaders in the legal profession. This issue spotlights Level’s current programming and its new five-year strategic plan. By drawing attention to flaws in the legal system, and tackling the root causes of injustice, Innocence Canada and Level strengthen the rule of law. LexisNexis Canada and its employees are proud to support the work of both organizations. We also raise money for other worthy causes, including the #TorontoStrongFund, established in response to the April 2018 Toronto van attack. 2 TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF ADVOCACY FOR THE WRONGLY CONVICTED Innocence Canada, formerly the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted (AIDWYC), is a national, non-profit organization that advocates for the wrongly convicted across Canada. -

The Emerging Role of Innocence Projects in the Correction of Wrongful Conviction in Australia

Investigating Innocence: The Emerging Role of Innocence Projects in the Correction of Wrongful Conviction in Australia Author Weathered, Lynne Published 2003 Journal Title Griffith Law Review Copyright Statement © 2003 Griffith Law School. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/6223 Link to published version https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10383441.2003.10854511 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au INVESTIGATING INNOCENCE The Emerging Role of Innocence Projects in the Correction of Wrongful Conviction in Australia * Lynne Weathered DNA technology has uncovered the significant problem of wrongful conviction in the United States. Australians tend to have great faith in our criminal justice system; however, innocent people have also been wrongly convicted in this country. As a society, we must never become complacent about our criminal justice system: we must continually address areas likely to be relevant to the incidence of wrongful conviction, and we need mechanisms for the proper review of claims of innocence. Following in the footsteps of Innocence Projects in the United States, Innocence Projects in Australia are emerging as a resource for the investigation of claims of wrongful conviction with the aim of freeing innocent persons from incarceration. The majority of wrongful conviction claims will not involve DNA evidence, making the investigative work of Innocence Projects more complex and time-consuming, but also a task in which student resources are particularly valuable. To enhance the effectiveness of addressing claims of wrongful conviction, adoption of legislation or procedures is required. -

Advocate for Wrongly Convicted, David Milgaard Fights to Keep Innocent out of ‘Cages’”

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge Canada Homepage This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles On 2 OCTOBER 2014 Valerie Fortney of the Calgary Herald reported “Advocate for wrongly convicted, David Milgaard fights to keep innocent out of ‘cages’”. David Milgaard, who spent 23 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit, spoke at the John Howard Society in Calgary on Thursday as part of the first Wrongful Conviction Day. Photograph by: Leah Hennel David Milgaard is not by definition an angry man. “I love my life,” says the youthful 62-year-old, who has called Calgary home for the past six years. “I’m grateful for everything I have today.” Stir his memories, though, and the old demons rush over him like an ocean wave. “I had trouble sitting with some men recently who were wrongfully convicted,” he says. “I wish to say that anger isn’t there, but it is there.” Despite the unwelcome emotions such encounters trigger, Milgaard — who spent more than 23 years in a Canadian prison for a crime he didn’t commit — stands outside the John Howard Society on Thursday morning, the featured speaker at a press conference launching the first Wrongful Conviction Day. Together with his long time lawyer Greg Rodin, who also lives in Calgary, Milgaard speaks passionately to the gathered media about the issues surrounding the wrongly convicted. “We cannot let innocent people be disqualified from life, from beauty,” he says. “In our Canadian prisons right now, we have wrongly convicted men, we have wrongly convicted women and, in some cases, children, sitting still right now inside cages.” The new day of recognition is being hosted by the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted, a national non-profit organization that grew out of the Justice for Guy Paul Morin Committee. -

Wrongful Convictions and Forensic Science: the Need to Regulate Crime Labs

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2006 Wrongful Convictions and Forensic Science: The Need to Regulate Crime Labs Paul C. Giannelli Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Evidence Commons Repository Citation Giannelli, Paul C., "Wrongful Convictions and Forensic Science: The Need to Regulate Crime Labs" (2006). Faculty Publications. 149. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/149 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. GIANNELLI.PTD 12/17/2007 2:47:57 PM WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS AND FORENSIC SCIENCE: THE NEED TO REGULATE CRIME LABS* PAUL C. GIANNELLI** DNA testing has exonerated over 200 convicts, some of whom were on death row. Studies show that a substantial number of these miscarriages of justice involved scientific fraud or junk science. This Article documents the failures of crime labs and some forensic techniques, such as microscopic hair comparison and bullet lead analysis. Some cases involved incompetence and sloppy procedures, while others entailed deceit, but the extent of the derelictions—the number of episodes and the duration of some of the abuses, covering decades in several instances—demonstrates that the problems are systemic. Paradoxically, the most scientifically sound procedure—DNA analysis—is the most extensively regulated, while many forensic techniques with questionable scientific pedigrees go completely unregulated.