Chapter 3 Existing Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 5.4.3: Risk Assessment – Flood

SECTION 5.4.3: RISK ASSESSMENT – FLOOD 5.4.3 FLOOD This section provides a profile and vulnerability assessment for the flood hazard. HAZARD PROFILE This section provides hazard profile information including description, extent, location, previous occurrences and losses and the probability of future occurrences. Description Floods are one of the most common natural hazards in the U.S. They can develop slowly over a period of days or develop quickly, with disastrous effects that can be local (impacting a neighborhood or community) or regional (affecting entire river basins, coastlines and multiple counties or states) (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], 2006). Most communities in the U.S. have experienced some kind of flooding, after spring rains, heavy thunderstorms, coastal storms, or winter snow thaws (George Washington University, 2001). Floods are the most frequent and costly natural hazards in New York State in terms of human hardship and economic loss, particularly to communities that lie within flood prone areas or flood plains of a major water source. The FEMA definition for flooding is “a general and temporary condition of partial or complete inundation of two or more acres of normally dry land area or of two or more properties from the overflow of inland or tidal waters or the rapid accumulation of runoff of surface waters from any source (FEMA, Date Unknown).” The New York State Disaster Preparedness Commission (NYSDPC) and the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) indicates that flooding could originate from one -

Low Bridge, Everybody Down' (WITH INDEX)

“Low Bridge; Everybody Down!” Notes & Notions on the Construction & Early Operation of the Erie Canal Chuck Friday Editor and Commentator 2005 “Low Bridge; Everybody Down!” 1 Table of Contents TOPIC PAGE Introduction ………………………………………………………………….. 3 The Erie Canal as a Federal Project………………………………………….. 3 New York State Seizes the Initiative………………………………………… 4 Biographical Sketch of Jesse Hawley - Early Erie Canal Advocate…………. 5 Western Terminus for the Erie Canal (Black Rock vs Buffalo)……………… 6 Digging the Ditch……………………………………………………………. 7 Yankee Ingenuity…………………………………………………………….. 10 Eastward to Albany…………………………………………………………… 12 Westward to Lake Erie………………………………………………………… 16 Tying Up Loose Ends………………………………………………………… 20 The Building of a Harbor at Buffalo………………………………………….. 21 Canal Workforce……………………………………………………………… 22 The Irish Worker Story……………………………………………………….. 27 Engineering Characteristics of Canals………………………………………… 29 Early Life on the Canal……………………………………………………….. 33 Winter – The Canal‘sGreatest Impediment……………………………………. 43 Canal Expansion………………………………………………………………. 45 “Low Bridge; Everybody Down!” 2 ―Low Bridge; Everybody Down!‖ Notes & Notions on the Construction & Early Operation of the Erie Canal Initial Resource Book: Dan Murphy, The Erie Canal: The Ditch That Opened A Nation, 2001 Introduction A foolhardy proposal, years of political bickering and partisan infighting, an outrageous $7.5 million price tag (an amount roughly equal to about $4 billion today) – all that for a four foot deep, 40 foot wide ditch connecting Lake Erie in western New York with the Hudson River in Albany. It took 7 years of labor, slowly clawing shovels of earth from the ground in a 363-mile trek across the wilderness of New York State. Through the use of many references, this paper attempts to describe this remarkable construction project. Additionally, it describes the early operation of the canal and its impact on the daily life on or near the canal‘s winding path across the state. -

Summertime 2020 Hilary Lambert CLWN Steward Many People Have Been Noting That Nature’S Annual Seasonal Rounds Have Continued, Regardless of Our Human Problems

CAYUGA LAKE WATERSHED 2020 i2 Network It takes a Network to protect a watershed. News Summertime 2020 Hilary Lambert CLWN Steward Many people have been noting that nature’s annual seasonal rounds have continued, regardless of our human problems. As our human cacophony has died down, some have wondered if nature is emerging, edging outward. Here’s my recent experience: When I went outside to walk my dog at 5:30 a.m., a deer was sleeping in the front yard on the recently-mown grass, halfway between my bedroom window and Hanshaw Road. She woke up, stared at us, and ambled slowly across the empty road to the fields. here’s a redwing blackbird just down next door pond wandered freely and the out-of-doors during these interesting, the road who daily divebombs talkatively around my yard, unafraid tragic, and strange times. Tme, my dog, and the neighbors, I of my household. I have heard of many Many people have gone to the lake to suppose for getting too close to the family other such close encounters, since shortly paddle, walk, and swim, are hiking along nest. It is probable that a bobcat visited after the pandemic began and people- creeks and to waterfalls for solace and the backyard in April (falling off a white pressure retreated. release. Families and friends sheltered pine branch with a yowl), terrifying my Is it us, or is it them? In any case, we at lakeside cottages outside the usual cats. The mallard ducks situated at the should treasure our deeper immersion in summer season, to be together and avoid pandemic dangers. -

Ulysses Ithaca Antiques Mall, 1607 Trumansburg Rd

Touring the Towns of 1827, has been used as office, commercial, and residential space. Morning Glory, 89 Cayuga St, Trumansburg. 607-387-5305. Cemeteries C Tompkins County, New York At 1822 Trumansburg Rd is The Trees, a handsome early www.morningglory.com.laurie corner of Cemetery and Falls Sts, Trumansburg. See #7. Italianate house built in 1865 by James M. Mattison, owner of a Grove, popular nursery and tree farm on the site, which was started in Reunion House, 7550 Willow Creek Rd. 607-387-6553. Jones-Goodwin’s Point, Gorge Rd, west of Taughannock Farms 1845 and continued through the early 1870s. It is a private www.reunion-house.com Inn. residence today. Taughannock Farms Inn, Rt 89 at Taughannock Falls State Park. Quaker, see #9. 607-387-7711. www.t-farms.com. See #2. 9.9 Hector Monthly Meeting House, at 5066 Perry City Rd, St. James, Searsburg Rd, Trumansburg. 1 mile W of the Rt 96 intersection on the north side of the road, Westwind, 1662 Taughannock Blvd. 607-387-3377. this white clapboard building was erected c.1910, for the area’s www.fingerlakes.net/westwind Historical Markers Ħ Quaker community. There is also a cemetery. An old stone post Camp Site – Taughannock Falls State Park, north side. Site of at the driveway entrance has the carved letters HMMSOF, Antiques and Speciality Shops S 1788 exploring party’s camp. Hector Monthly Meeting, Society of Friends. Today the building Cold Springs Pottery Studio, 4088 Cold Springs Rd. Samuel Weyburn – Taughannock Falls State Park, south side. is used by the Ithaca Society of Friends for summer worship only. -

Appendices Section

APPENDIX 1. A Selection of Biodiversity Conservation Agencies & Programs A variety of state agencies and programs, in addition to the NY Natural Heritage Program, partner with OPRHP on biodiversity conservation and planning. This appendix also describes a variety of statewide and regional biodiversity conservation efforts that complement OPRHP’s work. NYS BIODIVERSITY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The New York State Biodiversity Research Institute is a state-chartered organization based in the New York State Museum who promotes the understanding and conservation of New York’s biological diversity. They administer a broad range of research, education, and information transfer programs, and oversee a competitive grants program for projects that further biodiversity stewardship and research. In 1996, the Biodiversity Research Institute approved funding for the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation to undertake an ambitious inventory of its lands for rare species, rare natural communities, and the state’s best examples of common communities. The majority of inventory in state parks occurred over a five-year period, beginning in 1998 and concluding in the spring of 2003. Funding was also approved for a sixth year, which included all newly acquired state parks and several state parks that required additional attention beyond the initial inventory. Telephone: (518) 486-4845 Website: www.nysm.nysed.gov/bri/ NYS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION The Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) biodiversity conservation efforts are handled by a variety of offices with the department. Of particular note for this project are the NY Natural Heritage Program, Endangered Species Unit, and Nongame Unit (all of which are in the Division of Fish, Wildlife, & Marine Resources), and the Division of Lands & Forests. -

GROWN HERE. MADE HERE. Vescelius New York Wine & Plants Frst N.Y

grown here. made here. Seneca Lake Winery Association, Inc. Association, Seneca Lake Winery 320 Suite Street, Franklin 2 North 14891 York Glen, New Watkins (877) 536-2717 (607) 535-8080 or [email protected] senecalakewine.com Here’s to the farmers, Situated around the deep, blue waters of Seneca Lake, our unique, glacially-formed And their vision. landscape and sloping shorelines create an To the growers, ideal cool-climate growing region that allows And their bounty. our members to grow a number of delicate vinifera grapes like Riesling, Chardonnay, and To the makers. other aromatic whites. Red varieties such as To the artists. Cabernet Franc and Pinot Noir also thrive here, resulting in an array of diferent varieties and To their craft. styles, most made from grapes harvested within Here’s to the tasters, federally recognized Seneca Lake American Viticultural Area (AVA). We guarantee that you’ll And the diners. find a wine perfect for you! To the lovers, And friends. Our member wineries promote a spirit of cooperation to develop an outstanding and To the locals, comprehensive wine tourism region and are And the wanderers. dedicated to creating premium, award-winning wines suitable for every palate. Furthermore, To the Finger Lakes. Seneca Lake Wine Trail member wineries To this lake. are committed to enhancing the region’s economy and quality of life through a variety To these hills. of innovative and cooperative events and These waters. programs year-round. These vines. Since our organizations founding in 1986, These grapes. we have become a popular wine and grape Here’s to our passion. -

Tales from the Littoral Zone the Origin of the Fish Species of Cayuga and Seneca Lakes Mel Russo Finger Lakes Area Naturalist and Life-Long Resident

CAYUGA LAKE WATERSHED 2015 i2 Network It takes a Network to protect a watershed. News Tales from the Littoral Zone The Origin of the Fish Species of Cayuga and Seneca Lakes Mel Russo Finger Lakes area naturalist and life-long resident Our story begins at an unreasonable point in time, some 550 million years ago when what is now New York State was at the bottom of an epicontinental sea.Gradually, the As the most recent ice age ended, the Burbot (Lota lota) was an early arrival to Seneca and Cayuga lakes. Today this species is listed by NYS entire state, along with much of the northeast, fully DEC as “among the most unusual fish that anglers can encounter.” Please emerged from the sea by about 200 million years ago. see the end of this article for more information. or the next 100 million years or so, the somewhat level land would provide the first vehicle for the re-population of aquatic Fthat was Upstate New York, was then eroded by the flow of fauna into the Finger Lakes. many centuries of torrential precipitation. The wearing away As the front of the ice mass retreated, the young rivers of the land created twelve nearly parallel river valleys, which produced by the melt flowed southward to fill the valleys that included the mighty Seneca and Cayuga Rivers. The easternmost the glacier recently helped to shape. These numerous streams set of six flowed northward into a depression which was encountered other existing freshwater bodies, rivers and the precursor of the Great Lakes Basin. -

Greater Syracuse Area Waterway Destinations and Services

Waterway Destinations and Services Map Central Square Y¹ `G Area Syracuse Greater 37 C Brewerton International a e m t ic Speedway Bradbury's R ou d R Boatel !/ y Remains of 5 Waterfront nt Bradbury Rd 1841 Lock !!¡ !l Fort Brewerton State Dock ou Caughdenoy Marina C !Z!x !5 Alb County Route 37 a Virginia St ert Palmer Ln bc !x !x !Z Weber Rd !´ zabeth St N River Dr !´ E R North St Eli !£ iver R C a !´ A bc d !º UG !x W Genesee St H Big Bay B D !£ E L ÆJ !´ \ N A ! 5 O C !l Marina !´ ! Y !5 K )§ !x !x !´ ÆJ Mercer x! Candy's Brewerton x! N B a Memorial 5 viga Ç7 Winter Harbor r Y b Landing le hC Boat Yard e ! Cha Park FA w nn e St NCH Charley's Boat Livery

Erie Canalway Map & Guide 2012

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide 2012 Fairport, Keith Boas Explore. Learn. Discover. Getting Here The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 cleared the way for goods, people, The New York State Thruway (I-90) and Amtrak parallel the Erie Canal and ideas to flow from New York City to the Great Lakes and beyond. from Albany to Buffalo. Northway I-87 Travelers marveled at the canal’s locks and low bridges, and encountered provides access to the Champlain colorful characters, lively adventures, and hometown hospitality all Canal from Albany to Whitehall. But to see the best parts of the Erie Canalway, along the way. you’ll want to get off the Interstates. You can too. Discover for yourself what you can’t read in a history book: State and county roads thread through the hamlets, villages, and cities that New York’s legendary canals—where exceptional scenery, history, culture, grew along the waterways and provide and adventure await. Here are a few of the things you’ll want to explore: the best access to canal towns and sites. Try these routes: What’s Inside Today’s Canals Canal Communities • NY Rte 31 in western New York Get On Board! . 2 Rent a canal boat for a few hours or a Stroll through villages, towns, and cities • NY Rte 5 and 5S in the weeklong vacation, step on board a tour whose canal waterfronts still open onto Walk! Cycle! Jog! Mohawk Valley boat, or explore in your own cruiser, historic Main Streets with one-of-a-kind The Erie Canalway Trail • NY Rte 48 and County Rte 57 along kayak or canoe. -

An Introductory Guide to Wetland Plants Important to Waterfowl and Marsh Management in Central New York by Michael L

An Introductory Guide to Wetland Plants Important to Waterfowl and Marsh Management in Central New York by Michael L. Schummer Roosevelt Waterfowl Ecologist Roosevelt Wild Life Station SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Disclaimer: This is not a complete guide to the wetland plants of New York, but a list of plants commonly occurring in managed and unmanaged wetlands that are 1/ food for waterfowl and other seed eating birds, 2/ cover for invertebrates eaten by ducklings and other fish and wildlife, and 3/ invasive plants that often require control to ensure a diversity of native plants can flourish. This should not serve as an ultimate guide to wetland plant management. Always follow herbicide labeling and regulations. Always obtain the proper permits before conducting wetland management activities. Introduction: In my experience, few waterfowl enthusiasts (birders and hunters) fully understand the diversity of plants used by waterfowl for food and cover. My intent is to provide a VERY basic introductory guide to these plants and descriptions about their identification and management. In Marsh History, I provide some historical context about the loss of wetlands in the central New York region and why management of wetlands are critical to ensure quality habitats are available for migratory waterfowl. In Important Wetland Plants as Food, I cover the most common plants producing seeds, tubers, and vegetation eaten by waterfowl. Here I express the utility of annual plants in producing an abundance of food for waterfowl because these plants DO NOT return the next year from their roots; their only way of continuing to exist is from their production of seeds that must germinate the following year. -

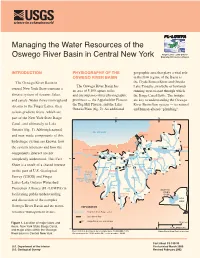

Managing the Water Resources of the Oswego River Basin in Central New York

Managing the Water Resources of the Oswego River Basin in Central New York INTRODUCTION PHYSIOGRAPHY OF THE geographic area that plays a vital role OSWEGO RIVER BASIN in the flow regime of the Basin is The Oswego River Basin in the Clyde/Seneca River and Oneida The Oswego River Basin has Lake Troughs, two belts of lowlands central New York State contains a an area of 5,100 square miles running west-to-east through which diverse system of streams, lakes, and encompasses three physiographic the Barge Canal flows. The troughs and canals. Water flows from upland provinces — the Appalachian Plateau, are key to understanding the Oswego the Tug Hill Plateau, and the Lake streams to the Finger Lakes, then River Basin flow system — its natural Ontario Plain (fig. 2). An additional and human-altered “plumbing”. to low-gradient rivers, which are part of the New York State Barge 77° 76° Canal, and ultimately to Lake Ontario (fig. 1). Although natural LAKE ONTARIO OSWEGO 8 and man-made components of this 7 6 5 OSWEGO RIVER 3 hydrologic system are known, how 2 A ONEID Oneida Lake 1RIVER ROME the system functions and how the ROCHESTER 21 Cross 23 24 22 components interact are not CLYDE RIVER Lake LOCK 30 29 SENECA 28A 27 26 Onondaga 43° RIVER SYRACUSE completely understood. This Fact 28B 25 Lake Sheet is a result of a shared interest CS1 Skaneateles Conesus Canandaigua CS4 CS2&3 Lake Otisco Lake Lake GENEVA AUBURN Lake on the part of U.S. Geological Honeoye Lake Seneca Lake Survey (USGS) and Finger Hemlock Owasco Canadice Lake Lake Lakes-Lake Ontario Watershed Lake Keuka Lake Cayuga Protection Alliance (FL-LOWPA) in OSWEGO Lake ITHACA RIVER WATKINS BASIN facilitating public understanding GLEN NEW and discussion of the complex YORK Oswego River Basin and its water- EXPLANATION resource-management issues. -

The 'Ups” and “Downs” of Cayuga Lake……

The ‘Ups” and “Downs” of Cayuga Lake…… OR How I learned to stop worrying and love the changes in Cayuga Lake water levels. Contributors: Dr. Craig Williams New York State Museum Mike Riley Local Canal Historian Bill Hecht Local History/Photography Archivist Bill Kappel USGS Hydrogeologist 10. With Seneca Lake 1,564 and Keuka Lake 388.0 100-yr Flood level 386.0 Major Flood-damage level Minor Flood damage level 384.0 Maximum Target Lake-level Elevation 382.0 380.0 378.0 Olympus, where they say, the god’s eternal mansion stands unmoved, never rocked by galewinds, never drenched by rains, nor do the drifting snows assail it, no, the clean air stretches away without a cloud, and a great radiance plays across that world where the blithe gods live all their days in bliss. From: The Odyssey, Chapter IV, by Homer The Historical Perspective…. Baldwinsville Lyons Clyde Jordan Syracuse 1825 Map Montezuma Upstate New York The Historical Perspective…. Burr Atlas, 1839 No Bridge? No Problem………………….. The Historical Perspective…. Seneca County Map, 1850 The Historical Perspective…. 1860s Map – Seneca-Cayuga Canal at present day Mudlock 380.4 390.4 386.4 The Historical Perspective…. New York State Barge Canal Engineers Report 1862 Richmond Aqueduct – Past and Present 1850 Map with 2009 cultural features approximation of: Routes 5 &20 NYS- Thruway NYS – Barge Canal Footnotes on the water level of Cayuga Lake and the Seneca River from the records of the New York State Senate and Assembly New York State Senate – 1852 “Fall of the [Seneca] River from the Rochester-Syracuse railroad bridge to Baldwinsville [dam] is 12.54 feet.