Sub¡Nitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfiltment of the Requirements for the Degree of University of Manito

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AND GEOLOGY of the SURROUNDING AREA I

. " ... , - .: ~... GP3/10 ~ " . :6',;, J .~~- -i-~ .. '~ MANITOBA MINES BRANCH DEPARTMENT OF MfNES AND NATURAL RESOURCES LAKE ST. MARTIN CRYPTO~EXPLOSION CRATER .. AND GEOLOGY OF THE SURROUNDING AREA i . , - by H. R. McCabe and B. B. Bannatyne Geological Paper 3/70 Winnipeg 1970 Electronic Capture, 2011 The PDF file from which this document was printed was generated by scanning an original copy of the publication. Because the capture method used was 'Searchable Image (Exact)', it was not possible to proofread the resulting file to remove errors resulting from the capture process. Users should therefore verify critical information in an original copy of the publication. (i) GP3/10 MANITOBA M]NES BRANCH DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND NATURAL RESOURCES LAKE ST. MARTIN CRYPTO·EXPLOSION CRATER AND GEOLOGY OF THE SURROUNDING AREA by H. R. McCabe and B. B. Bannatync • Geological Paper 3/70 Winnipeg 1970 (ii) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction' r Previous work I .. Present work 2 Purpose 4 Acknowledgcmcnts 4 Part A - Regional geology and structural setting 4 Post-Silurian paleogeography 10 Post-crater structure 11 Uthology 11 Precambrian rocks 12 Winnipeg Fomlation 13 Red River Fomlation 14 Stony Mountain Formation 15 Gunn Member 15 Gunton Member 16 Stoncwall Formation 16 Interlake Group 16 Summary 17 Part B - Lake St. Martin crypto-explosion crater 33 St. Martin series 33 Shock metamorphism 33 Quartz 33 Feldspar 35 Biotite 35 Amphibole 36 Pseudotachylyte 36 Altered gneiss 37 Carbonate breccias 41 Polymict breccias 43 Aphanitic igneous rocks - trachyandcsitc 47 Post·crater Red Beds and Evaporites (Amaranth Formation?) 50 Red Bed Member 50 Evaporite Member 52 Age of Red Bed·Evaporite sequence 53 Selected References 67 . -

![For Cody Caves Provincial Park [Electronic Resource]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1756/for-cody-caves-provincial-park-electronic-resource-371756.webp)

For Cody Caves Provincial Park [Electronic Resource]

Kootenay Region MANAGEMENT DIRECTION STATEMENT September 2004 for Cody Caves Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protectio Environmental Provincial Park Stewardship Division Cody Caves Provincial Park: Management Direction Statement 2004 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data British Columbia. Environmental Stewardship Division. Kootenay Region. Management direction statement for Cody Caves Provincial Park [electronic resource] Cover title. At head of title: Kootenay Region. Running title: Cody Caves Provincial Park management direction statement. “September 2004” Available on the Internet. ISBN 0-7726-5356-9 1. Cody Caves Park (B.C.) 2. Provincial parks and reserves – British Columbia. 3. Ecosystem management - British Columbia – Cody Caves Park. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. I. Title. II. Title: Cody Caves Provincial Park management direction statement. FC3815.C62B74 2005 333.78’30971162 C2005-960107-8 Cody Caves Provincial Park: Management Direction Statement 2004 Cody Caves Provincial Park Approvals Page Foreword This management direction statement for Cody Caves Provincial Park provides management direction until such time as a more detailed management plan may be prepared. Cody Caves Provincial Park protects an extensive cave system, and associated karst features. Approvals: Wayne Stetski Nancy Wilkin Regional Manager Assistant Deputy Minister Kootenay Region Environmental Stewardship Division Date: Date: Cody Caves Provincial Park: Management Direction Statement 2004 Table of -

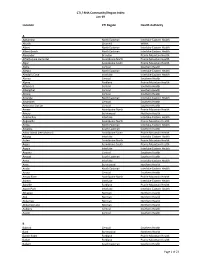

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Outlet Channels

Project Description Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin Outlet Channels Prepared for: Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Submitted by: Manitoba Infrastructure January 2018 Project Description – January 2018 Table of Contents 1 GENERAL INFORMATION AND CONTACTS ................................................... 1 1.1 Nature of the Project and Proposed Location ..................................................... 1 1.2 Proponent Information ........................................................................................ 3 1.2.1 Name of the Project ......................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Name of the Proponent ................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Address of the Proponent ................................................................................ 3 1.2.4 Chief Executive Officer .................................................................................... 3 1.2.5 Principal Contact Person ................................................................................. 3 1.3 Jurisdictions and Other Parties Consulted .......................................................... 6 1.4 Environmental Assessment Requirements ......................................................... 7 1.4.1 Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (Canada) ............................ 7 1.4.2 The Environment Act (Manitoba) ..................................................................... 8 1.5 Other Regulatory Requirements ........................................................................ -

Carte Des Zones Contrôlées Controlled Area

280 RY LAKE 391 MYSTE Nelson House Pukatawagan THOMPSON 6 375 Sherridon Oxford House Northern Manitoba ds River 394 Nord du GMo anitoba 393 Snow Lake Wabowden 392 6 0 25 50 75 100 395 398 FLIN FLON Kilometres/kilomètres Lynn Lake 291 397 Herb Lake 391 Gods Lake 373 South Indian Lake 396 392 10 Bakers Narrows Fox Mine Herb Lake Landing 493 Sherritt Junction 39 Cross Lake 290 39 6 Cranberry Portage Leaf Rapids 280 Gillam 596 374 39 Jenpeg 10 Wekusko Split Lake Simonhouse 280 391 Red Sucker Lake Cormorant Nelson House THOMPSON Wanless 287 6 6 373 Root Lake ST ST 10 WOODLANDS CKWOOD RO ANDREWS CLEMENTS Rossville 322 287 Waasagomach Ladywood 4 Norway House 9 Winnipeg and Area 508 n Hill Argyle 323 8 Garde 323 320 Island Lake WinnBRiOpKEeNHEgAD et ses environs St. Theresa Point 435 SELKIRK 0 5 10 15 20 East Selkirk 283 289 THE PAS 67 212 l Stonewall Kilometres/Kilomètres Cromwel Warren 9A 384 283 509 KELSEY 10 67 204 322 Moose Lake 230 Warren Landing 7 Freshford Tyndall 236 282 6 44 Stony Mountain 410 Lockport Garson ur 220 Beausejo 321 Westray Grosse Isle 321 9 WEST ST ROSSER PAUL 321 27 238 206 6 202 212 8 59 Hazelglen Cedar 204 EAST ST Cooks Creek PAUL 221 409 220 Lac SPRINGFIELD Rosser Birds Hill 213 Hazelridge 221 Winnipeg ST FRANÇOIS 101 XAVIER Oakbank Lake 334 101 60 10 190 Grand Rapids Big Black River 27 HEADINGLEY 207 St. François Xavier Overflowing River CARTIER 425 Dugald Eas 15 Vivian terville Anola 1 Dacotah WINNIPEG Headingley 206 327 241 12 Lake 6 Winnipegosis 427 Red Deer L ake 60 100 Denbeigh Point 334 Ostenfeld 424 Westgate 1 Barrows Powell Na Springstein 100 tional Mills E 3 TACH ONALD Baden MACD 77 MOUNTAIN 483 300 Oak Bluff Pelican Ra Lake pids Grande 2 Pointe 10 207 eviève Mafeking 6 Ste-Gen Lac Winnipeg 334 Lorette 200 59 Dufresne Winnipegosis 405 Bellsite Ile des Chênes 207 3 RITCHOT 330 STE ANNE 247 75 1 La Salle 206 12 Novra St. -

Karst Inventory Standards and Vulnerability Assessment Procedures for British Columbia

Karst Inventory Standards and Vulnerability Assessment Procedures for British Columbia Prepared by The Karst Task Force for the Resources Inventory Committee January 2001 Version 1.0 © 2001 The Province of British Columbia Published by the Resources Inventory Committee National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Karst inventory standards and vulnerability assessment procedures for British Columbia [computer file] Available on the Internet. Issued also in printed format on demand. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-4488-8 1. Karst – British Columbia. 2. Geological surveys – British Columbia. I. Resources Inventory Committee (Canada). Karst Task Force. GB600.4.C3K37 2001 551.447 C2001-960052-6 Additional Copies of this publication can be purchased from: Government Publications Centre Phone: (250) 387-3309 or Toll free: 1-800-663-6105 Fax: (250) 387-0388 www.publications.gov.bc.ca Digital Copies are available on the Internet at: http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/ric Karst Inventory Standards Preface The Karst Inventory Standards and Vulnerability Assessment Procedures for British Columbia describes provincial standards for conducting karst inventories at various survey intensity levels, and outlines procedures for deriving karst vulnerability ratings. This document builds upon the recommendations and proposals for conducting karst inventories and vulnerability assessments described in A Preliminary Discussion of Karst Inventory Systems and Principles (KISP) for British Columbia (Research Program Working Paper 51/2000). The KISP document was widely reviewed by national and international karst experts, industry, and by staff from the Ministry of Forests and the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. It is intended that these standards and procedures be implemented on an interim basis for a two-year period. -

Home Care Office Listings

HOME CARE OFFICE LISTINGS LOCATION CATCHMENT AREA OFFICE CONTACT NUMBER(S) ARBORG - Arborg Community Health Office Arborg, Matheson Island RM, Pine Dock, Riverton, 204-376-5559 ext. 1 & 7 317 River Road, Box 423, Arborg, MB R0C 0A0 Icelandic Lodge & Sunrise Lodge Fax: 204-376-5970 ASHERN – Lakeshore General Hospital Ashern, RM of Grahamdale & Siglunes, Camper, 204-768-5225 1 Steenson Drive, Ashern, MB, R0C 0A0 Glencora, Gypsumville, Moosehorn, Mulvihill, Pioneer- Fax: 204-768-3879 Heritage, Vogar BEAUSEJOUR – 71107 Hwy 302S Beausejour & Whitemouth 204-268-6747 Box 209, Beausejour, MB R0E 0C0 204-268-6721 204-268-6720 Fax: 204-268-6727 ERIKSDALE – (SEE LUNDAR) FISHER BRANCH – Fisher Branch PCH Chalet Lodge, Dallas, Fisher Branch, Fisher River, Hodgson, 204-372-7306 Poplarfield, Poplar Villa, RM of Fisher 7 Chalet Dr., Box 119, Fisher Branch, MB R0C 0Z0 Fax: 204-372-8710 GIMLI – Gimli Community Health Office Arnes, Camp Morton, Fraserwood, Gimli RM, Parts of 204-642-4581 Armstrong RM, Meleb, malonton, Matlock (Rd 97N), 120-6TH Avenue, Box 250, Gimli, MB R0C 1B0 204-642-4596 Rockwood RM, Ponemah, Sandy Hook & Winnipeg Beach 204-642-1607 Fax: 204-642-4924 LAC DU BONNET – Lac du Bonnet District Health Centre Bird River, Great Falls, Lac du Bonnet, Lee River, Leisure 204-345-1217 89 McIntosh Street, Lac du Bonnet, MB R0E 1A0 Falls, Pinawa, Pointe du Bois, Wendigo, White Mud Falls 204-345-1235 Fax: 204-345-8609 LUNDAR/ERIKSDALE – Lundar Health Centre Coldwell RM, Town of Clarkleigh, Lundar, RM & Town of 204-762-6504 Eriksdale 97-1ST Street South, Box 296, Lundar, MB R0C 1Y0 Fax: 204-762-5164 OAKBANK – Kin Place Health Complex Anola, Cooks Creek, Dawson Rd (portion), Deacons 204-444-6139 689 Main Street, Oakbank, MB R0E 1J0 Corner, Dugald, Hazelridge, Queensvalley, Meadow 204-444-6119 Crest, Oakbank, Pine Ridge, Symington St. -

Public Accounts of the Province of Manitoba for the Fiscal Year Ending

200 CASH PAYMENTS TO CORPORATIONS, ETC., 1967 -1968 GOVERNMENT OF THE PROVINCE OF MANITOBA Cash Paid to Corporations, Firms, Individuals, Municipalities, Cities, Towns and Villages, Arranged in Alphabetical Order to Show the Amount Paid to Each Payee Where the Total Payments Exceed $1,000.00 for the Year Ended 31st March, 1968. For Salaries, Page No. 178 Name Address Amount Name Address Amount “A” Acme Welding & Supply Ltd., Winnipeg . 7,281.88 A Active Electric Co., Acres & Company Ltd., Winnipeg .$ 2,287.40 H. C., Niagara Falls, Ont. 81,967.21 A. & A. Frozen Foods Ltd., Acres Western Ltd., Winnipeg . 1,031.29 Winnipeg . 12,926.22 A. E. I. Telecommunication, Winnipeg . 4,745.67 Adam, A., Ste. Rose . 1,232.79 Adams Supply Company A. & F. Trucking Service, Ltd., A., Winnipeg . 1,645.22 Virden . 1,829.88 Adams, Alfred Lloyd & A. & H. Equipment Leasing Adams, Laura, Winnipeg 21,312.75 Ltd., Winnipeg . 4,264.79 Adams, Lorraine M., A. & N. Groceteria, Dauphin . 1,250.53 Thompson . 5,020.75 Adam’s Store, Skowman .... 1,959.37 Abbott Laboratories Ltd., Adams, Walter, Montreal, Que. 6,576.29 Portage la Prairie . 1,078.00 Abelard-Schuman Canada Adanac Household Supply Ltd., Toronto, Ont. 2,152.56 (1961) Ltd., Winnipeg . 24,919.97 Aberhart Memorial Sana¬ Addison-Wesley Canada torium, Edmonton, Alta... 2,376.00 Ltd., Don Mills, Ont. 13,983.59 Abex Industries of Canada Addison’s, Carberry . 1,498.60 Limited, Montreal, Que..... 2,305.00 Addressograph-Multigraph Abitibi Manitoba Paper of Canada Ltd., Ltd., Pine Falls . 7,540.03 Toronto, Ont. -

Poplar River Poplarville

Poplar River Poplarville Berens River Pauingassi Little Grand Rapids Dauphin River Jackhead Princess Harbour Gypsumville Bloodvein Matheson Island Homebrook Lake St. Martin Long Body Creek St. Martin St. Martin Station Pine Dock St. Martin Junction Little Saskatchewan Fairford Reserve Little Bullhead Loon Straits Fairford Fisher Bay Red Rose Hilbre Steep Rock Dallas Fisher River Cree Nation Faulkner Grahamdale Peguis Spearhill Harwill Moosehorn Aghaming Hodgson Seymourville Hollow Water Ashern Oakview Shornclie Hecla Bissett Fisher Branch Manigotagan Camper Morweena Broad Valley Riverton Mulvihill Arborg Vogar Dog Creek Poplareld Hnausa Spruce Bay Eriksdale Silver Arnes Spruce Bay Silver Harbour Rembrandt Heights Glen Bay Little Black River Chateld Deerhorn Lake Forest Brewster Bay Meleb Loch Woods Victoria Beach Ness Country Lundar Narcisse Shorepointe Village Kings Park Fort Alexander Fraserwood Aspen Park Gimli Pelican Beach Powerview-Pine Falls Loni Beach Bélair Malonton South Beach Grand Beach Grand Marais Siglavik Sandy Hook Golf Course St. Georges Silver Falls Oak Point Inwood Sandy Hook Beaconia Komarno Winnipeg Beach Great Falls White Mud Falls Dunnottar Stead Brokenhead St. Laurent Teulon Reserve Thalberg Pinawa Bay Netley Gunton Peterseld Lee River Lake Francis Brightstone Pointe du Bois Libau Lac du Bonnet Balmoral Clandeboye Milner Ridge Woodlands Argyle Pinawa Stonewall Selkirk Ladywood East Selkirk Warren Tyndall Beausejour Seven Sisters Falls Little Britain Gonor River Hills Grosse Isle Lockport Marquette Stony Kirkness Seddons Corner Mountain Narol St. Ouens W. Pine Ridge Molson Whitemouth Cloverleaf Meadows Oakbank Hazelridge Rosser Dugald Glass Anola Elma Rennie Winnipeg Navin Vivian Ste. Rita Deacons Corner West Hawk Hadashville Lake McMunn Prawda East Braintree. -

Cave/Karst Management- an Integrated Ecosystems Approach

TABLE OF CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION PROVINCIAL CROWN LAND CAVE POLICY MINISTRY OF FORESTS' ROLE AND RESPONSIBILITIES COMMUNICATION AND CO-OPERATION PUBIC ACCESS CAVE/KARST MANAGEMENT- AN INTEGRATED ECOSYSTEMS APPROACH A. INVENTORY, CLASSIFICATION AND RECORDS Procedures and responsibilities B. SURFACE CONSIDERATIONS Planning and Construction for Roads and Landings Right-of-way felling, clearing and subgrade construction Pits and Quarries Fuel Storage Panning and Operations for Falling and Yarding Ground Skidding Silviculture Planning, Scarification and Burning C. SUBSURFACE CONSIDERATIONS - Visitor Use and Safety Cave User Management Guidelines D. NON-GOVERNMENT MANAGEMENT OF CAVES E. PUBLIC SAFETY AND LIABILITY F. CAVE RESCUE REFERENCES GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDICES INTRODUCTION British Columbia has a surface area of approximately 95 million hectares, of which 85% is crown owned forest and range land managed by the Ministry of Forests. Extensive road networks created by timber harvesting have opened the way for many recreational activities. One of these activities, which has become increasingly popular in recent years, is the sport of caving. More than 750 caves, predominantly on Vancouver Island, have been explored; and there may be hundreds, if not thousands more to be discovered. Initially recreational cavers were content to find, explore, photograph and map their finds. However, when some of the more significant caves became vandalized and or destroyed through indiscriminate resource use, individual cavers and caving groups began to advocate government participation in the management of the cave resource. These caves are a unique non-renewable resource with geological, scenic, educational, cultural, biological, hydrological, paleontological and recreation values. The management of caves [both surface and subsurface resources] is considered to be an essential component of integrated resource management. -

Meteorological Comparison of Three Cave Systems

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects Honors College at WKU 2019 Meteorological Comparison of Three Cave Systems Matthew Wine Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Geology Commons, and the Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Wine, Matthew, "Meteorological Comparison of Three Cave Systems" (2019). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 835. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/835 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. METEOROLOGICAL COMPARISON OF THREE CAVE SYSTEMS A Capstone Experience/Thesis Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree Bachelor of Science with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By: Matthew Wine ***** Western Kentucky University 2019 CE/T Committee: Approved by: Dr. Patricia Kambesis, Advisor Dr. Greg Goodrich __________________________________ Dr. Dennis Wilson Advisor Department of Geography & Geology Copyright by: Matthew Wine 2019 ABSTRACT Cave systems are home to delicate underground ecosystems that can be affected by changes in surface atmospheric conditions which in turn affect underground meteorology. Modern human use of caves is typically for tourism, so understanding surface-underground weather-climate interactions is important when caves carry streams that are prone to flooding in response to surface precipitation. The purpose of this research is to document the effects of surface weather conditions on cave meteorology in three different cave system types located in different geographic locations including an island, the central USA, and at high elevations in British Columbia.