OCERINT PAPER Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theatre of Tennessee Williams: Languages, Bodies and Ecologies

Barnett, David. "Index." The Theatre of Tennessee Williams: Languages, Bodies and Ecologies. London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2014. 295–310. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 17:43 UTC. Copyright © Brenda Murphy 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. INDEX Major discussions of plays are indicated in bold type . Williams ’ s works are entered under their titles. Plays by other authors are listed under authors ’ names. Actors Studio 87, 95 “ Balcony in Ferrara, Th e ” 55 Adamson, Eve 180 Bankhead, Tallulah 178 Adler, Th omas 163 Barnes, Clive 172, 177, Albee, Edward 167 268n. 17 Alpert, Hollis 189 Barnes, Howard 187 American Blues 95 Barnes, Richard 188 Ames, Daniel R. 196 – 8, Barnes, William 276 203 – 4 Barry, Philip 38 Anderson, Maxwell Here Come the Clowns 168 Truckline Caf é 215 Battle of Angels 2 , 7, 17, 32, Anderson, Robert 35 – 47 , 51, 53, 56, 64, 93, Tea and Sympathy 116 , 119 173, 210, 233, 272 “ Angel in the Alcove, Th e ” Cassandra motif 43 4, 176 censorship of 41 Ashley, Elizabeth 264 fi re scene 39 – 40 Atkinson, Brooks 72, 89, Freudian psychology in 44 104 – 5, 117, 189, 204, political content 46 – 7 209 – 10, 219 – 20 production of 39, 272 Auto-Da-Fe 264 reviews of 40 – 1, 211 Ayers, Lemuel 54, 96 Th eatre Guild production 37 Baby Doll 226 , 273, 276 themes and characters 35 Bak, John S. -

The Glass Menagerie

The Glass Menagerie By: Joe M., Emanuel M., Adrian M., Graham O. Choices of the Author Hubris Symbolism Character Foil Hubris Hubris: A great or foolish amount of pride or confidence Amanda Wingfield Euphoria for the past 17 Gentleman Callers Scene I Unrealistic Expectations for Children Lack of Motivation from both Laura and Tom Symbolism Glass Symbol for Laura: brittle, fragile representing sensitivity Amanda and Tom arguments always end with glass breaking Scene 3: Tom hits shelf of glass with overcoat “Laura cries out as if wounded” (24) Scene 7: Tom smashes his glass on the floor “Laura screams in fright” (96) At the peak of the fight when it has ended, someone leaves Character Foil Foil: A foil is another character in a story who contrasts with the main character, usually to highlight one of their attributes Jim to Tom That really good friend that does everything better and your parents are like why you can’t be like them. Tom: Lacks ambition and goes to movies Jim: Big dreams and public speaking classes Laura to Amanda Literary Lenses Marxist Psychoanalytic New Historicism Marxist The Wingfields, members middle class, function under the brutal economic laws of capitalist society during the Great Depression of the 1930's. Tom Wingfield is “a poet in a warehouse” I go to the movies because I like adventure. Adventure is something I don't have much at work, so I go to the movies. (Williams, 39). The temper of work in the warehouse does not satisfy Tom’s poetic ambitions This foreshadows Tom’s to escape from his life of hard labor and to enroll in The Union of Merchant Seamen Marxist (Contd.) Theme 1: Alienation within the workforce ambitions do not lie in the warehouse Theme 2: Limitations of Capitalism Inequality, visible in Tom’s dependency on unfulfilling manual labor Psychoanalytic Motif: Escape and Imprisonment Tom Wingfield “Yes, I have tricks in my pocket, I have things up my sleeve. -

The Glass Menagerie Teachers´Packaug

The Glass Menagerie Plot Overview The Glass Menagerie is known as a “ memory play” because it is based on the way the plays narrator, Tom, remembers events. The story is a told to us by Tom Wingfield, a merchant marine looking back on the Depression years he spent with his overbearing Southern genteel mother, Amanda, and his physically disabled, cripplingly shy sister, Laura. While Amanda strives to give her children a life beyond the decrepit St. Louis tenement they inhabit, she is herself trapped by the idealised memory of her life past . Tom, working at a shoe factory and paying the family’s rent, finds his own escape in drinking and going to the movies, while Laura pours her energy into caring for her delicate glass figurines. Tom, pressured by his mother to help find Laura a suitable husband, invites an acquaintance from the factory to the apartment, a powerful possibility that pushes Amanda deeper into her obsessions and makes Laura even more vulnerable to shattering, exposed like the glass menagerie she treasures. Williams’ intensely personal and brilliantly tender masterpiece exposes the complexity of our memories, and the ways in which we can never truly escape them. Detailed Summary Scene 1 “I give you truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.” – Tom The narrator, Tom, explains directly to the audience that the scenes are “memory,” therefore nonrealistic. Memory omits (leaves out) details and exaggerates them according to the value of the memory. Memory, as he explains, rests mainly in the heart. We learn from the narrator that the gentleman- caller character is the most realistic because he is from the world of reality and symbolizes the “expected something that we live for.” The photograph is of the father who left the family a long time ago. -

Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams's the Glass Menagerie

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 11-13-2007 Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie, Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, Marsha Norman's night, Mother, and Paula Vogel's How I Learned to Drive Dipa Janardanan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Janardanan, Dipa, "Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie, Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, Marsha Norman's night, Mother, and Paula Vogel's How I Learned to Drive." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/23 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Images of Loss in Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie , Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman , Marsha Norman’s ‘night , Mother , and Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive by DIPA JANARDANAN Under the Direction of Matthew C. Roudané ABSTRACT This dissertation offers an analysis of the image of loss in modern American drama at three levels: the loss of physical space, loss of psychological space, and loss of moral space. The playwrights and plays examined are Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie (1945), Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949), Marsha Norman’s ‘night, Mother (1983), and Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive (1998). -

The Glass Menagerie by TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Directed by JOSEPH HAJ PLAY GUIDE Inside

Wurtele Thrust Stage / Sept 14 – Oct 27, 2019 The Glass Menagerie by TENNESSEE WILLIAMS directed by JOSEPH HAJ PLAY GUIDE Inside THE PLAY Synopsis, Setting and Characters • 4 Responses to The Glass Menagerie • 5 THE PLAYWRIGHT About Tennessee Williams • 8 Tom Is Tom • 11 In Williams’ Own Words • 13 Responses to Williams • 15 CULTURAL CONTEXT St. Louis, Missouri • 18 "The Play Is Memory" • 21 People, Places and Things in the Play • 23 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Reading and Understanding • 26 Guthrie Theater Play Guide Copyright 2019 DRAMATURG Carla Steen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Akemi Graves CONTRIBUTOR Carla Steen EDITOR Johanna Buch Guthrie Theater, 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 teachers and individual personal use, no part of this Play Guide may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE (toll-free) or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director writing from the publishers. Some materials published herein are written especially for our Guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the imagination, Endowment for the Arts. This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation stir the heart, open the mind and build community through the illumination of our by the Minnesota State Legislature. The Minnesota State Arts common humanity. -

Women's Monologues

WOMEN’S MONOLOGUE’S Bargaining by Kellie Powell Hannah: Ryan, there's something I have to tell you. (Pause.) I was born in 1931. I never lied to you, I am 23. But I've been 23 since the year 1954. I know, I know. It's impossible, right? No one lives forever? But, sometimes they do. In 1953, I got married. A few weeks after the wedding, I suddenly fell ill. My husband took me to a hospital. I was there for almost a week. I was in so much pain. And no one could say for sure what was wrong. One night, in the hospital, a stranger came to see me. He told me, "Janie, you're going to die tomorrow." That was my name then, the name I was born with. This man, the stranger, he offered me a chance to live forever. He said, "You can die tomorrow, or you can live forever. Stay young forever." Well, of course my first thought was, the devil has come to tempt me. He wasn't the devil. And of course, I don't believe in the devil anymore. There are powerful beings on this earth, but man created Satan. And God, for that matter. My point is, this man offered me a chance to live. And I took it. I will live forever. I will never age. I cannot be harmed, not physically. I can't be hurt by bullets, or knives, or fire, or even explosions. I can't be hurt by diseases - in fact, I can't even catch a cold. -

External Content.Pdf

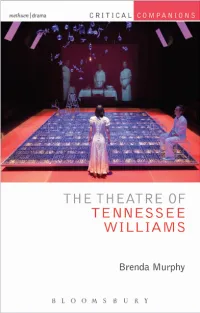

i THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy is Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus at the University of Connecticut. Among her 18 books on American drama and theatre are Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collaboration in the Theatre (1992), Understanding David Mamet (2011), Congressional Theatre: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film, and Television (1999), The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity (2005), and as editor, Critical Insights: Tennessee Williams (2011) and Critical Insights: A Streetcar Named Desire (2010). In the same series from Bloomsbury Methuen Drama: THE PLAYS OF SAMUEL BECKETT by Katherine Weiss THE THEATRE OF MARTIN CRIMP (SECOND EDITION) by Aleks Sierz THE THEATRE OF BRIAN FRIEL by Christopher Murray THE THEATRE OF DAVID GREIG by Clare Wallace THE THEATRE AND FILMS OF MARTIN MCDONAGH by Patrick Lonergan MODERN ASIAN THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE 1900–2000 Kevin J. Wetmore and Siyuan Liu THE THEATRE OF SEAN O’CASEY by James Moran THE THEATRE OF HAROLD PINTER by Mark Taylor-Batty THE THEATRE OF TIMBERLAKE WERTENBAKER by Sophie Bush Forthcoming: THE THEATRE OF CARYL CHURCHILL by R. Darren Gobert THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy Series Editors: Patrick Lonergan and Erin Hurley LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Methuen Drama An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 © Brenda Murphy, 2014 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. -

Directing Tennessee Williams' the Glass Menagerie in 2017 Jon Cole Wimpee University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Are Unicorns Extinct in the Modern World?: Directing Tennessee Williams' The Glass Menagerie in 2017 Jon Cole Wimpee University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wimpee, Jon Cole, "Are Unicorns Extinct in the Modern World?: Directing Tennessee Williams' The Glass Menagerie in 2017" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2928. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2928 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Are Unicorns Extinct in the Modern World ?: Directing Tennessee Williams' The Glass Menagerie in 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Theater by Jon Cole Wimpee Texas State University Bachelor of Fine Arts, Acting - 2003 August 2018 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _________________________________ Michael Landman, M.F.A. Thesis Director _________________________________ ___________________________________ Patricia Martin, M.F.A. Shawn D. Irish, M.F.A. Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT What follows is a description of my process directing The Glass Menagerie by Tennessee Williams. I’ve made an effort to track the journey I undertook starting from my earliest encounter with the play and the selection of the story as a thesis project. This document contains my initial script analysis, notes from design meeting collaborations, casting decisions, general research approaches, the rehearsal process, performance insights, and evaluations after completion. -

Tennessee Williams's Auto-Da-Fé

Self-Punishment for a “Heresy”: Tennessee Williams’s Auto-Da-Fé FUJITA Hideki ါలĶĵาक़ܮ໐ڠ૽ڠ५ఱີ ˎˌˍˍාˎ Self-Punishment for a “Heresy”: Tennessee Williams’s Auto-Da-Fé Self-Punishment for a “Heresy”: Tennessee Williams’s Auto-Da-Fé FUJITA Hideki Tennessee Williams’s Auto-Da-Fé is a one-act play collected in the original edition of 27 Wagons Full of Cotton and Other One-Act Plays, published in 1945. The title of this short play may attract a reader’s notice. It refers to the burning of a heretic by the Spanish Inquisition. Auto-Da-Fé is not, however, a period play; it is set in New Orleans in the twentieth century. But it ends with the main character subjecting himself to the gruesome penalty. Thus, the title suggests the way he meets his GRRP$VZHVKDOOVHHLWLVDOVRVLJQL¿FDQWLQWKDWLWDOOXGHVWRZKDWKHLVJXLOW\RIZKDWKLV³KHUHV\´LV The narrative opens with the description of the setting. The action takes place on the front porch of Madame Duvenet’s old frame cottage in the Vieux Carré of New Orleans. The opening stage direction is as follows. Scene: The front porch of an old frame cottage in the Vieux Carré of New Orleans. There are palm or banana trees, one on either side of the porch steps: pots of geraniums and other vivid ÀRZHUVDORQJWKHORZEDOXVWUDGH7KHUHLVDQHIIHFWRIVLQLVWHUDQWLTXLW\LQWKHVHWWLQJHYHQWKH ÀRZHUVVXJJHVWLQJWKHULFKQHVVRIGHFD\1RWIDURIIRQ%RXUERQ6WUHHWWKHOXULGSURFHVVLRQRI bars and hot-spots throws out distance-muted strains of the juke-organs and occasional shouts of laughter. Mme. Duvenet, a frail woman of sixty-seven, is rocking on the porch in the faint, sad glow of an August sunset. -

PLAYS of TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Fulfillment of the Requirements For

/ 1h THE FUGITIVE KIND IN THE MAJOR PLAYS OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By John 0. Gunter, B. A. Denton, Texas January, 1968 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page - I I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. VAL IN BATTLE OF ANGELS. 13 III. KILROY IN CASINO REAL. 21 IV. VAL IN ORPHEUS DESCENDING. 33 V. CHANCE IN SWEETBIRDOFYOUTH..0.#.0.e.0.#.0.0.045 VI. SHANNON IN THE NIGHT OF THE IGUANA . 55 VII. CONCLUSION . .0 . .......-. 68 BIBLIOGRAPHY. - - . - - - - . - - 75 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION There are numerous ways to approach the works of a playwright critically; one is to examine the individual writer's "point of view" in order to define what the man is trying to "say" from his chosen vantage point. This tactic seems as appropriate as any in approaching the works of Tennessee Williams. The plays of Tennessee Williams are written from an in- dividual's point of view; i. e., none of the plays are con- cerned with a social or universal outlook as such; rather each play "takes the shape of a vision proceeding from the consciousness of the protagonist."1 In other words, each one of Williams' plays "belongs" to one central "camera eye" character. Everything that happens is directly related to this character and his perception of and his subsequent adjustment to his environment. Furthermore, the majority of these central characters fall into certain categories which recur in the Williams canon. Some of these categories have been critically labeled and defined, but none of the studies Esther Merl6 Jackson, The Broken World of Tennessee Williams (Milwaukee, 1965), p. -

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE the GLASS MENAGERIE Teacher Resource Guide by Nicole Kempskie TABLE of CONTENTS

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE THE GLASS MENAGERIE Teacher Resource Guide by Nicole Kempskie TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 THE PLAY . 2 . The .Story . 2 . The .Characters . 3 . The .Writer . 4 . Additional .Resources . 5 ELEMENTS OF STYLE . 6 . Poetic .Language . 6 . The .Memory .Play . 7 . Plastic .Theater . 7 . Autobiography . 8 THEMES & SYMBOLS . 9 . Thematic .Elements . 9 . Symbols . 10 . Additional .Resources . 10 PRODUCTION NOTES . 11 . From .the .Director . 11 . Post-Performance .Discussion . 11 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES . 12 RESOURCES/BIBLIOGRAPHY . 20 . INTRODUCTION In this ‘memory play’ Tennessee Williams transports us “ into private worlds where desire clashes with obdurate reality, where loss supplants hope. After more than a half a century we continue to be drawn to a play that explores so many aspects of the human condition. ” Robert Bray, Introduction to The Glass Menagerie (New Directions Edition) Welcome to the teacher resource guide for Tennessee Williams’ play, The Glass Menagerie. We are delighted that students will be able to experience this American classic in a stunning new Broadway production starring two-time Academy Award winner Sally Field as Amanda Wingfield and two-time Tony Award winner Joe Mantello as Tom Wingfield. Director Sam Gold, winner of the Tony Award for the musicalFun Home, will be recreating a production he first directed at Toneelgroep Amsterdam. The Glass Menagerie provides many learning opportunities for students in areas related to: › playwright Tennessee Williams and his legacy; › one of the most popular American plays in history; › the literary devices and thematic elements embodied in The Glass Menagerie; and › understanding The Glass Menagerie through a personal lens. HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE Arts experiences resonate most strongly for students when themes and ideas from the play can be aligned to your curriculum. -

Reflections on the Glass Menagerie

Reflections on the Glass Menagerie Recalling his sister Rose’s hobby of collecting small glass articles during her youth in St. Louis, Tennessee Williams stated that these glass figures “By poetic association came to represent, in [his] memory, all the softest emotions that belong to the recollection of things past. They stood for all the small and tender things that relieve the austere pattern of life and make it endurable to the sensitive.” On another occasion, he wrote that the glass animals came symbolized the “fragile, delicate ties that must be broken, that you inevitably break, when you try to fulfill yourself.” The Glass Menagerie opened at the Civic Theatre in Chicago on December 26, 1944, and in Williams’ words “it was an event which terminated one part of my life and began another about as different in all external circumstances as could well be imagined. I was snatched out of virtual oblivion and thrust into sudden prominence, and from the precarious tenancy of furnished rooms about the country I was removed to a suite in a first-class Manhattan hotel.” This success, however, was to be forever haunted by what he had left behind. 1. Tennessee Williams Photograph by Ian Deen [undated] 2003.0147 Rehearsals for The Glass Menagerie in Chicago did not go well, and as late as December 24, Williams was making changes to the dialogue. Initial public interest in the play was minimal, and the day after it opened, the producers were considering closing it down. The play may very well have closed had it not been for two Chicago reviewers: Ashton Stevens of the Chicago Herald American and Claudia Cassidy of the Chicago Daily Tribune.