Baptist Membership in Rural Leicestershire, 1881-1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limes Farmyard, Main Street, Kilby, Leicestershire

The Farmhouse Illustrative Layout Unit 2 FOR SALE Residential Development/Conversion Opportunity Limes Farmyard, Main Street, Kilby, Leicestershire. LE18 3TD A 2.58 Acre (1.04 Ha) site benefiting from Full Planning Consent for the conversion of two barns into residential dwellings and the construction of one new detached dwelling. The sale also includes an existing Farmhouse requiring renovation and Paddock land extending to 1.56 Acres. LOCATION DIRECTIONS Limes Farmyard is located on Main Street, Kilby, Leicestershire. From Junction 21 of the M1 follow the A5460 towards Fosse LIMES FARMYARD LE18 3TD. Kilby is a popular South Leicestershire village boasting Park/Leicester and take the fourth exit, signposted both a well-regarded Pub and a Primary School (rated as “Good” Narborough/Fosse Park. At the lights turn left onto the A563 in the most recent Ofsted report, dated October 2016). signposted towards Wigston. After approximately 3 miles turn right MAIN STREET onto Welford Road and stay on this over the roundabout, travelling Just 3 miles north of Kilby is the town of Wigston which offers a through Wigston. 3 miles after leaving Wigston turn left towards range of services and leisure facilities. The village of Fleckney lies Kilby and travel down into the village where the site will be on your KILBY approximately 4 miles to the south-east of the site and offers a right hand side shortly after entering the village, identifiable by way number of services including a Post Office, GP Surgery and of a Mather Jamie For Sale board. Convenience Store. LEICESTERSHIRE PLANNING Kilby benefits from excellent transport links and Junction 21 of the The site benefits from Full Planning Consent granted by Blaby M1 is situated a short drive from the site. -

Huncote Village News Issue 44 – Christmas 2011 Brought to You by Huncote Parish Council

HUNCOTE VILLAGE NEWS ISSUE 44 – CHRISTMAS 2011 BROUGHT TO YOU BY HUNCOTE PARISH COUNCIL STAY SAFE THIS CHRISTMAS HUNCOTE COMMUNITY DAY • Keep your home and belongings safe, don’t leave Huncote Parish Council would like to thank everyone who valuables on display. attended the Huncote Community Day on Saturday 26th • Don’t drink and drive – decide on a designated November at the Community Centre and who came to the driver; are you safe to drive the next morning? parish council stall to help us with our consultation on • Don’t put up with domestic abuse, help is improving the play equipment in the play areas in Huncote available. on the Denman Lane/Critchlow Road playing field, • Switch off fairy lights and extinguish candles As mentioned in the Autumn Newsletter, the Parish council when you leave the room. would like to gain opinions to back out grant applications in the hope of raising funds to cover the costs. If you would like advice about any of these safety tips ring the Blaby Community Safety Team on 0116 The day provided us with a greater understanding of 272 7725 or visit www.blaby.gov.uk. people’s thoughts and views on the park as well as many valuable suggestions and ideas for how you would like to see it improved, but we would still like more responses. CHRISTMAS TREE RECYCLING SITES Further ideas from anyone who uses the park now or in the People in Blaby are being urged to start their new year on future, including children, parents, and grandparents are a ‘green footing’ by recycling their Christmas tree when most welcome. -

Early Baptists in Leicestershire and Rutland

Early Baptists in Leicestershire and Rutland (IV) PARTICULAR BAPTISTS; LATER DEVELOPMENTS Kilby-Amesby The origin of the Kilby-Arnesby church in south Leicestershir~ owes little if anything to the Baptist churches described so far.l It was led by Richard Farmer of Kilby, lind seems to have been organ ised ID the wake of the Act of Uniformity of 1662. It quickly became widespread, and maintained congregational church government, be lievers' baptism, personal election, and the final perseverance of God's people. Farmer's father Richard was for some years a Kilby churchwarden,2 as was his own son Richard.3 How often did families that produced churchwardens also produce Nonconformist leaders at critical times like 1662? Other instances among seventeenth century Midland Bap tists are the Curtises of Harringworth, Northamptonshire, and Na thaniel Locking of Asterby, Lincolnshire.4 Our Richard, a "yeoman"5 and "gent.",6 traded in silk. 7 He was a keen student,8 and left "unto my Sonne Isaack all my Books Except Phisick and Schirorgury Books", which went to his daughter Anne. Whatever theological works he owned went to the only child to join their father's church.9 Richard was buried in July, 1688, in Kilby parish churchyard.10 Farmer's influence was such that he spent three weeks in the county gaol during Monmouth's rebellion,l1 and distraint of goods for breach es of the Conventicle Act cost him £110 one year. 12 Although his meetings were called "Anabaptist" in 1669, his first licences, in November, 1672, as teacher at his own house in Kilby, were as "Congr[egationalist]".13 Houses at Wigston Magna, Fleckney, Tur Langton, and possibly Leicester, were licensed similarly at the same time. -

Ageing Well Guide a Directory of Services, Clubs and Activities in Blaby District

Ageing Well Guide A directory of services, clubs and activities in Blaby District Published June 2016 Introduction Welcome to the new Ageing Well Guide for Blaby District. Our Ageing Population remains a priority for Blaby District Council. It is our vision that people are able to enjoy happy, healthy and independent lives, feeling involved and valued in their community during later life. Cllr David Freer – Portfolio Holder for Partnerships & Corporate Services – says: ‘Residents and professionals alike have told us what a valuable resource the Older Persons’ Guide has been and this new edition is bigger than ever. The Council and its partners provide a number of schemes that support our vision for our ageing population. The new Ageing Well Guide includes information about these and the numerous activities that are taking place across our parishes that are all helping in some way to reduce isolation and improve health and wellbeing’. The frst part of this guide provides information about district-wide services that provide help on issues such as health and social care, transport, community safety, money advice and library services. The second part of the guide gives details of clubs and activities taking place in each parish within the district, including GP practices, social or lunch clubs, ftness and exercise classes and special interest or hobby groups. 2 Blaby District Council has taken care to ensure the information in this booklet is accurate at the time of publication. All information has been provided by third parties and the Council cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies in the information or any changes that may arise, such as changes to any fees, charges or activities listed. -

Leicestershire County Council Z33 and C39 Order, Kilby

Leicestershire County Council Democratic Services & Governance Manager Date: 23rd August 2018 Slaby District Council My ref: WTJ/HTWMT/3568 Council Offices Your ref: Desford Road Contact: William Jackson Narborough Phone: 0116 3055782 Leicestershire Email: [email protected] LE19 2EP Dear Sir/Madam SECTIONS 118 AND 119 - HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 DIVERSION OF PUBLIC FOOTPATH 233 (PART) AND EXTINGUISHMENT OF FOOTPATH C39 (PART), KILBY I refer to previous correspondence and would inform you that approval has been given for the making of an Order in respect of the above-mentioned matter. In connection with this matter I am now enclosing for your Council's use a copy of the appropriate Public Notice, Order and explanatory statement and would be grateful if you would acknowledge receipt and display a copy of the Notice in your offices from 30th August 2018 to 28th September 2018. Any representation or objection to the making of the Order should be made to this Council not later than 28th September 2018. Yours faithfully William Jackson Legal Assistant (Order Making) Chief Executive's Department Leicestershire County Council, County Hall, Glenfield, Leicestershire LE3 8RA Telephone: 0116 232 3232 Fax: 0116 305 6161 Minicam: 0116 305 6870 John Sinnott CBE, MA, Dipl. PA, Chief Executive Lauren Haslam, LLB(Hons), Dip.LG. Director of Law & Governance www.leicestershire.gov.uk LEICESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL NOTICE OF MAKING OF DIVERSION ORDER AND EXTINGUISHMENT ORDER SECTION 119 - HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 · PUBLIC FOOTPATH 233 (PART) PARISH OF KILBY, DISTRICT OF BLABY PUBLIC PATH DIVERSION ORDER 2018 The above Order made on 1?1h August 2018 will divert the part of Footpath 233 which extends from point "E" on the plan, situate at Grid Reference 46216 29549, in an easterly direction across an agricultural field, through point "D" on the plan, for a distance of approximately 235 metres, to point "F" on the plan, situate at its junction with Wistow Road at Grid Reference 46240 29548. -

Moving Order Kilby to Husbands Bosworth HTWMT

THE LEICESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL (A5199, FROM HUSBANDS BOSWORTH IN THE DISTRICT OF HARBOROUGH TO KILBY BRIDGE IN THE DISTRICT OF BLABY AND C5504 SADDINGTON ROAD, SHEARSBY IN THE DISTRICT OF HARBOROUGH) (IMPOSITION OF 50MPH SPEED LIMIT) ORDER 202 THE LEICESTERSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL hereby gives notice that it proposes to make an Order under Sections 5 and 84 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 (“the Act”), and of all other enabling powers, and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act, the effect of which will be: 1. To impose a 50mph Speed Limit on lengths of the A5199 in the parishes of Husbands Bosworth, Mowsley, Knaptoft, Shearsby, Arnesby and Kilby from Husbands Bosworth to Kilby Bridge and on part of C5504 Saddington Road, Shearsby. A copy of the proposed Order, together with plans illustrating the proposals and an explanatory statement giving the Council's reasons for proposing to make the Order may be inspected during normal office hours at my offices, Room 200, County Hall, Glenfield, Leicester LE3 8RA, at the offices of Harborough District Council, The Symington Building, Adam and Eve Street, Market Harborough LE16 7AG, Blaby District Council, Desford Road, Leicester, LE19 2EP and on the Parish Notice Boards of Husbands Bosworth, Shearsby, Arnesby and Kilby Parish Councils and Mowsley and Knaptoft Parish Meetings. Documents can also be viewed online at https://www.leicestershire.gov.uk/roads-and- travel/cars-and-parking/traffic-management-consultations . Objections to the proposals, specifying the grounds on which they are made, should be sent in writing to the undersigned by not later than 31st January 2020 quoting reference JM/HTWMT/4587. -

Crow Mills Way Countesthorpe/ South Wigston

Crow Mills Way Countesthorpe/ South Wigston Be Healthy, Walk Local GP Towing Path ce River Sen Crow Mill Bridge Entrance er Sen Crow Mills Way iv ce R Countesthorpe/South Wigston Entrance The paths here allow a circular walk with elevated views over Countesthorpe Road South Leicestershire. This walk runs along a disused railway line Mill Lane and through beautiful woodland adjacent to the Grand Union Canal and the River Sence. Crow Mills Way Small car park adjacent to site Disused Railway Key: Distance: 0.9 miles /1.5 km/ 2,088 steps Gradient: Level Moderate and Steep Time: 25 minutes approx Pushchair Friendly Kissing Gate Benches Walking boots required muddy in places Track Lay-by Track Be Healthy, Walk Local Part of a series of leaflets to introduce you to eight strategic sites in and around Blaby with a range of local walking opportunities for you to enjoy. The walks range from 20 minute strolls to an energetic 5 mile round walk in Fosse Meadows. Several of the sites feature picnic areas and play areas for families to enjoy a day out in the countryside. Please remember when out walking to follow the countryside code and to wear appropriate clothing and footwear. A50 Glenfield Other walks in the series Kirby Muxloe M1 Leicester Forest East A563 Jubilee Park Thorpe A47 Astley The Osiers Braunstone Town B582 Glen Parva Fosse Shopping Park Nature Reserve Whistle Way & Meadows Thurlaston M69 Enderby Glen Parva Crow Mills Way A426 Narborough Huncote Whetstone Blaby Littlethorpe Potters Marston Elmesthorpe Welford Road B4114 Croft B581 Stoney Countesthorpe Stanton Cosby Kilby M1 M69 Foston A426 Sapcote Aston Bouskell Flamville Sharnford Whetstone Park Fosse Meadows Way Nature Area B4114 & Arboretum P0856 February 2016 P0856 February. -

Agenda Reports Pack (Public) 30/04/2015, 16.30

To Members of the Planning Committee Dear Councillor, Please find attached the following information items which relate to the PLANNING COMMITTEE taking place on THURSDAY, 30 APRIL 2015 at 4.30 p.m. INFORMATION ITEMS 5. Information Reports (Pages 3 - 8) Blaby District Council Council Offices Desford Road Narborough Leicestershire LE19 2EP Telephone: 0116 275 0555 Fax: 0116 275 0368 Minicom: 0116 284 9786 Web: www.blaby.gov.uk This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 5 INFORMATION REPORTS Committee Name of Report Officer Planning Committee – Delegated List Miss K. Ingles – 30/04/2015 Development Services Manager Tel: 0116 272 7565 Page 3 This page is intentionally left blank Page 4 DEVELOPMENT CONTROL COMMITTEE For Information Only APPROVALS ISSUED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 14/1059/1/HPX Mr Simon Smith Enderby Parish Council 13 Holyoake Street Enderby Leicestershire Rear dormer extension to form bedroom in roof space Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/0082/FUL Enderby Parish Council Next Plc Desford Road Enderby Three storey extension and alterations to rear elevation of existing office building Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/0084/HH Ms Vicky Belcham Countesthorpe Parish 22 The Elms Countesthorpe Leicestershire Council First floor side and front extensions and single storey side extension to north west elevation (including demolition of existing conservatory) Plan No. Name of Applicant and Development Parish 15/0131/FUL Miss Georgina Crumbie Glenfield Parish Council 15 Stamford Street Glenfield Leicestershire Change of use from retail unit (Use Class A1) to tanning and beauty salon (Sui generis). -

SAPCOTE NEWS Glenfield 56.68 Narborough 53.68 • Published by SRGMC Enderby 50.08 (Sapcote Recreational Ground Management Sapcote 47.50 Committee)

Issue: April 2007 S APCOTE NEWS YYourOUR Village VILLAGE Paper PAPER EDITORS: 2007/2008 Comparative Parish Council Precept Levels Christina Davey in Blaby District 59 Hinckley Road Tel: 273552 or It was reported in the last We can now report on what Sapcote, as reported in the issue that the Parish Council other parish councils within last issue, is levying a precept 07740 425447 had applied a less than Blaby District are charging below the £52.95 average for inflation increase to the per household based on Blaby parishes as the Emails: [email protected] Parish’s precept. Band D properties. following table shows. Council Charge per Household per year for Band D (£) Belinda Duggins Whetstone 88.74 6 Spring Gardens Braunstone 82.15 Tel: 271967 or Glen Parva 74.09 Blaby 73.94 07773 482399 Cosby 72.88 Countesthorpe 71.76 Huncote 63.42 SAPCOTE NEWS Glenfield 56.68 Narborough 53.68 • Published by SRGMC Enderby 50.08 (Sapcote Recreational Ground Management Sapcote 47.50 Committee). Stoney Stanton 42.78 Croft 39.66 • SRGMC has no opinions on the articles in this Thurlaston 39.32 edition. Leicester Forest East 34.82 Kirby Muxloe 34.07 • All articles submitted will be included in the earliest Kilby 30.62 edition where possible, Sharnford 29.78 and the editor on behalf Elmesthorpe 20.07 of the SRGMC reserves the right NOT to publish any material deemed to be unsuitable. WELCOME ALFIE DUGGINS!! • The views and opinions expressed in this and any On Friday 16th March our own edition are NOT those of editor Belinda Duggins gave birth the editors unless detailed to a baby boy. -

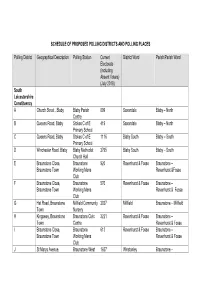

Schedule of Polling Districts

SCHEDULE OF PROPOSED POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES Polling District Geographical Description Polling Station Current District Ward Parish/Parish Ward Electorate (including Absent Voters) (July 2019) South Leicestershire Constituency A Church Street , Blaby Blaby Parish 809 Saxondale Blaby – North Centre B Queens Road, Blaby Stokes C of E 419 Saxondale Blaby – North Primary School C Queens Road, Blaby Stokes C of E 1116 Blaby South Blaby – South Primary School D Winchester Road, Blaby Blaby Methodist 2795 Blaby South Blaby – South Church Hall E Braunstone Close, Braunstone 920 Ravenhurst & Fosse Braunstone – Braunstone Town Working Mens Ravenhurst &Fosse Club F Braunstone Close, Braunstone 570 Ravenhurst & Fosse Braunstone – Braunstone Town Working Mens Ravenhurst & Fosse Club G Hat Road, Braunstone Millfield Community 2027 Millfield Braunstone – Millfield Town Nursery H Kingsway, Braunstone Braunstone Civic 3221 Ravenhurst & Fosse Braunstone – Town Centre Ravenhurst & Fosse I Braunstone Close, Braunstone 613 Ravenhurst & Fosse Braunstone – Braunstone Town Working Mens Ravenhurst & Fosse Club J St Marys Avenue, Braunstone West 1627 Winstanley Braunstone – Braunstone Town Social Centre Winstanley K1 Lakin Drive, Thorpe Astley Thorpe Astley 2624 Winstanley Braunstone – Thorpe Community Centre Astley L Kingsway North, Braunstone Town 825 Winstanley Braunstone – Braunstone Town Childrens Centre Winstanley M Park Road, Cosby Cosby Village Hall 2739 Cosby with South Cosby Whetstone N Station Road, Countesthorpe 1812 Countesthorpe Countesthorpe -

Settlement Audit and Hierarchy Report December 2020

Blaby District Council Settlement Audit and Hierarchy Report December 2020 Contents Section A: Introduction and Background .................................................................... 2 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 2 2 Background ...................................................................................................... 4 3 Local Context ................................................................................................... 6 4 Key Principles ................................................................................................... 6 5 National Planning Policy context ...................................................................... 7 Section B: Availability of Infrastructure, Services and Facilities ................................. 9 6. Methodology ..................................................................................................... 9 Summary of Results .............................................................................................. 11 7 Access to sustainable transport ...................................................................... 12 Summary of Results .............................................................................................. 14 8. Access to Employment ................................................................................... 15 Section C: Constraints ............................................................................................. -

Word Version

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Blaby in Leicestershire Report to The Electoral Commission June 2002 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND © Crown Copyright 2002 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report number 301. 2 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? 5 SUMMARY 7 1 INTRODUCTION 11 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 13 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 17 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 19 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 21 6 WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? 40 APPENDIX A Final Recommendations for Blaby: Detailed Mapping 42 A large map illustrating the proposed ward boundaries for Blaby Town and Narborough is inserted inside the back cover of this report. BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND 3 4 BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND WHAT IS THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to the Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 No 3692). The Order also transferred to the Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them.