104 Loeb and Northrop’S Experimental Manipulation of Longevity Was Deeply Related to the Discourse on Immortality at That Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ageing Haematopoietic Stem Cell Compartment

REVIEWS The ageing haematopoietic stem cell compartment Hartmut Geiger1,2, Gerald de Haan3 and M. Carolina Florian1 Abstract | Stem cell ageing underlies the ageing of tissues, especially those with a high cellular turnover. There is growing evidence that the ageing of the immune system is initiated at the very top of the haematopoietic hierarchy and that the ageing of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) directly contributes to changes in the immune system, referred to as immunosenescence. In this Review, we summarize the phenotypes of ageing HSCs and discuss how the cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic mechanisms of HSC ageing might promote immunosenescence. Stem cell ageing has long been considered to be irreversible. However, recent findings indicate that several molecular pathways could be targeted to rejuvenate HSCs and thus to reverse some aspects of immunosenescence. HSC niche The current demographic shift towards an ageing popu- The innate immune system is also affected by ageing. A specialized lation is an unprecedented global phenomenon that has Although an increase in the number of myeloid precur- microenvironment that profound implications. Ageing is associated with tissue sors has been described in the bone marrow of elderly interacts with haematopoietic attrition and an increased incidence of many types of can- people, the oxidative burst and the phagocytic capacity of stem cells (HSCs) to regulate cers, including both myeloid and lymphoid leukaemias, and both macrophages and neutrophils are decreased in these their fate. other haematopoietic cell malignancies1,2. Thus, we need individuals12,13. Moreover, the levels of soluble immune to understand the molecular and cellular mechanisms of mediators are altered with ageing. -

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements The cataloguing of the Manchester Medical Collections was made possible by a grant from the fund for Research Resources for Medical History set up by the Wellcome Trust. We are indebted to the Wellcome Trust for its continuing support for the history of medicine in The University of Manchester. Many colleagues and friends have helped to bring this volume to completion.We are grateful to all the contributors for their patience and forbearance during the long editing process. Dr Dorothy Clayton guided us expertly through the production of the volume and took much of the pain from that process. Many of the papers feature images taken from the JRUL collections and we would like to thank Carol Burrows for help with the selection and production of these illustrations. We are grateful to the following for permission to reproduce images: L'Institut Pasteur, p. 102; Tameside Local Studies and Archives Centre, Central Library, Ashton-under-Lyne, pp. 89, 105; The Royal Society, p. 159; The Medical Illustration Unit, Manchester Royal Infirmary, pp. 170, 172, 177, 178, 180; Anthony Bentley, Scientific Photographer, Faculty of Life Sciences, The University of Manchester, pp. 217, 218, 219 and 220. All other illustrations were taken from the collections held by the John Rylands University Library. John Pickstone Stella Butler 7 Contributors Julie Anderson is a Research Fellow at the Centre for the History of Science,Technology and Medicine and the Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine at The University of Manchester. Her areas of research include the history of disability and she has published on physical disability and war. -

The Creation of Neuroscience

The Creation of Neuroscience The Society for Neuroscience and the Quest for Disciplinary Unity 1969-1995 Introduction rom the molecular biology of a single neuron to the breathtakingly complex circuitry of the entire human nervous system, our understanding of the brain and how it works has undergone radical F changes over the past century. These advances have brought us tantalizingly closer to genu- inely mechanistic and scientifically rigorous explanations of how the brain’s roughly 100 billion neurons, interacting through trillions of synaptic connections, function both as single units and as larger ensem- bles. The professional field of neuroscience, in keeping pace with these important scientific develop- ments, has dramatically reshaped the organization of biological sciences across the globe over the last 50 years. Much like physics during its dominant era in the 1950s and 1960s, neuroscience has become the leading scientific discipline with regard to funding, numbers of scientists, and numbers of trainees. Furthermore, neuroscience as fact, explanation, and myth has just as dramatically redrawn our cultural landscape and redefined how Western popular culture understands who we are as individuals. In the 1950s, especially in the United States, Freud and his successors stood at the center of all cultural expla- nations for psychological suffering. In the new millennium, we perceive such suffering as erupting no longer from a repressed unconscious but, instead, from a pathophysiology rooted in and caused by brain abnormalities and dysfunctions. Indeed, the normal as well as the pathological have become thoroughly neurobiological in the last several decades. In the process, entirely new vistas have opened up in fields ranging from neuroeconomics and neurophilosophy to consumer products, as exemplified by an entire line of soft drinks advertised as offering “neuro” benefits. -

Eric Kandel Form in Which This Information Is Stored

RESEARCH I NEWS pendent, this system would be expected to [2] HEEsch and J E Bums. Distance estimation work quite well, since the new recruit bees by foraging honeybees, The Journal ofExperi mental Biology, Vo1.199, pp. 155-162, 1996. tend to take the same route as the experi [3] M V Srinivasan, S W Zhang, M Lehrer, and T enced scout bee. What dOJhe ants do when S Collett, Honeybee Navigation en route to they cover similarly several kilometres on the goal: Visual flight control and odometry, foot to look for food? Preliminary evidence The Journal ofExperimental Biology, Vol. 199, pp. 237-244, 1996. indicates that they don't use an odometer but [4] M V Srinivasan, S W Zhang, M Altwein, and instead might count steps! J Tautz, Honeybee Navigation: Nature and Calibration of the Odometer, Science, Vol. Suggested Reading 287, pp. 851-853, 1996. [1] Karl von Frisch, The dance language and OT Moushumi Sen Sarma, Centre for Ecological Sci ientation of bees, Harvard Univ. Press, Cam ences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, bridge, MA, USA, 1993. India. Email: [email protected] Learning from a Sea Snail: modify future behaviour, then memory is the Eric Kandel form in which this information is stored. Together, they represent one of the most valuable and powerful adaptations ever to Rohini Balakrishnan have evolved in nervous systems, for they In the year 2000, Eric Kandel shared the allow the future to access the past, conferring Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicinel flexibility to behaviour and improving the with two other neurobiologists: Arvid chances of survival in unpredictable, rapidly Carlsson and Paul Greengard. -

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 N1 Ueber Das Zustandekommen Der

書 名 等 発行年 出版社 受賞年 備考 Ueber das Zustandekommen der Diphtherie-immunitat und der Tetanus-Immunitat bei thieren / Emil Adolf N1 1890 Georg thieme 1901 von Behring N2 Diphtherie und tetanus immunitaet / Emil Adolf von Behring und Kitasato 19-- [Akitomo Matsuki] 1901 Malarial fever its cause, prevention and treatment containing full details for the use of travellers, University press of N3 1902 1902 sportsmen, soldiers, and residents in malarious places / by Ronald Ross liverpool Ueber die Anwendung von concentrirten chemischen Lichtstrahlen in der Medicin / von Prof. Dr. Niels N4 1899 F.C.W.Vogel 1903 Ryberg Finsen Mit 4 Abbildungen und 2 Tafeln Twenty-five years of objective study of the higher nervous activity (behaviour) of animals / Ivan N5 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by W. Horsley Gantt ; with the collaboration of G. Volborth ; and c1928 International Publishing 1904 an introduction by Walter B. Cannon Conditioned reflexes : an investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex / by Ivan Oxford University N6 1927 1904 Petrovitch Pavlov ; translated and edited by G.V. Anrep Press N7 Die Ätiologie und die Bekämpfung der Tuberkulose / Robert Koch ; eingeleitet von M. Kirchner 1912 J.A.Barth 1905 N8 Neue Darstellung vom histologischen Bau des Centralnervensystems / von Santiago Ramón y Cajal 1893 Veit 1906 Traité des fiévres palustres : avec la description des microbes du paludisme / par Charles Louis Alphonse N9 1884 Octave Doin 1907 Laveran N10 Embryologie des Scorpions / von Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 1870 Wilhelm Engelmann 1908 Immunität bei Infektionskrankheiten / Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov ; einzig autorisierte übersetzung von Julius N11 1902 Gustav Fischer 1908 Meyer Die experimentelle Chemotherapie der Spirillosen : Syphilis, Rückfallfieber, Hühnerspirillose, Frambösie / N12 1910 J.Springer 1908 von Paul Ehrlich und S. -

The Eagle 1946 (Easter)

THE EAGLE ut jVfagazine SUPPORTED BY MEMBERS OF Sf 'John's College St. Jol.l. CoIl. Lib, Gamb. VOL UME LIl, Nos. 231-232 PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ON L Y MCMXLVII Ct., CONTENTS A Song of the Divine Names . PAGE The next number shortly to be published will cover the 305 academic year 1946/47. Contributions for the number The College During the War . 306 following this should be sent to the Editors of The Eagle, To the College (after six war-years in Egypt) 309 c/o The College Office, St John's College. The Commemoration Sermon, 1946 310 On the Possible Biblical Origin of a Well-Known Line in The The Editors will welcome assistance in making the Chronicle as complete a record as possible of the careers of members Hunting of the Snark 313 of the College. The Paling Fence 315 The Sigh 3 1 5 Johniana . 3 16 Book Review 319 College Chronicle : The Adams Society 321 The Debaj:ing Society . 323 The Finar Society 324 The Historical Society 325 The Medical Society . 326 The Musical Society . 329 The N ashe Society . 333 The Natural Science Club 3·34 The 'P' Club 336 Yet Another Society 337 Association Football 338 The Athletic Club 341 The Chess Club . 341 The Cricket Club 342 The Hockey Club 342 L.M.B.C.. 344 Lawn Tennis Club 352 Rugby Football . 354 The Squash Club 358 College Notes . 358 Obituary: Humphry Davy Rolleston 380 Lewis Erle Shore 383 J ames William Craik 388 Kenneth 0 Thomas Wilson 39 J ames 391 John Ambrose Fleming 402 Roll of Honour 405 The Library . -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

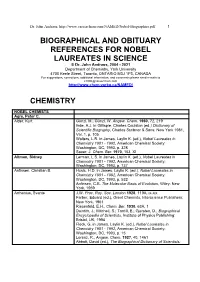

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

T. Colin Campbell, Ph.D. Thomas M. Campbell II

"Everyone in the field of nutrition science stands on the shoulders of Dr. Campbell, who is one of the giants in the field. This is one of the most important books about nutrition ever written - reading it may save your life." - Dean Ornish, MD THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF NUTRITION EVER CONDUCTED --THE-- STARTLING IMPLICATIONS FOR DIET, WEIGHT Loss AND LONG-TERM HEALTH T. COLIN CAMPBELL, PHD AND THOMAS M. CAMPBELL II FOREWORD BY JOHN ROBBINS, AUTHOR, DIET FOR A NEW AMERICA PRAISE FOR THE CHINA STUDY "The China Study gives critical, life-saving nutritional information for ev ery health-seeker in America. But it is much more; Dr. Campbell's expose of the research and medical establishment makes this book a fascinating read and one that could change the future for all of us. Every health care provider and researcher in the world must read it." -JOEl FUHRMAN, M.D. Author of the Best-Selling Book, Eat To Live . ', "Backed by well-documented, peer-reviewed studies and overwhelming statistics the case for a vegetarian diet as a foundation for a healthy life t style has never been stronger." -BRADLY SAUL, OrganicAthlete.com "The China Study is the most important book on nutrition and health to come out in the last seventy-five years. Everyone should read it, and it should be the model for all nutrition programs taught at universities, The reading is engrossing if not astounding. The science is conclusive. Dr. Campbells integrity and commitment to truthful nutrition education shine through." -DAVID KLEIN, PublisherlEditor Living Nutrition MagaZine "The China Study describes a monumental survey of diet and death rates from cancer in more than 2,400 Chinese counties and the equally monu mental efforts to explore its Significance and implications for nutrition and health. -

Human Cell and Organism Aging: Are There Limits? Interrupted Case Study on Cell Aging

Human Cell and Organism Aging: Are there Limits? Interrupted Case study on Cell Aging Teresa Gonya Department of Biological Sciences University of Wisconsin-Fox Valley Menasha, WI The search for the fountain of youth persists in advertising, and individuals are constantly bombarded with messages about diet, exercise, vitamins and minerals that can help prolong one’s life. The biological basis of aging is often not mentioned in the anti-aging promotions. Is it possible that a diet rich in protein, or fruits and vegetables can add years to your life? Is it possible that a vitamin or mineral ‘tonic’ can promote tissue repair and extend life? Is it possible that a vitamin drink can extend your normal life expectancy? Even clinical medicine focuses on developing new treatments that are based on preventing aging and maintaining organ longevity. We are told to exercise to keep our heart healthy and to stop smoking to prevent damage to body tissues, especially the lungs and blood vessels. The new field of regenerative medicine is based on the premise that stem cells may one day be able to repair tissue and return function to damaged organs. There are real limits to longevity that are based on genetics, lifestyle, medical history and sociology. (1) At the foundation of organism longevity is cell longevity. All organisms are composed of cells. Four different types of tissue cells form the basis of all organs that are found in any animal organism. Each type of tissue cell has a different ability to undergo mitosis and replace itself, should it become damaged or injured. -

Capital, Profession and Medical Technology: Royal College Of

Medical History, 1997, 41: 150-181 Capital, Profession and Medical Technology: The Electro-Therapeutic Institutes and the Royal College of Physicians, 1888-1922 TAKAHIRO UEYAMA* That it is undesirable that any Fellow or Member of the College should be officially connected with any Company having for its object the treatment of disease for profit. (Resolution of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 25 Oct. 1888.) That subject to the general provisions of Bye-law 190 the College desires so to interpret its Bye-law, Regulations, and Resolutions, as no longer to prohibit the official connection of Fellows and Members with medical institutes, though financed by a company, provided there be no other financial relation than the acceptance of a fixed salary or of fees for medical attendance on a fixed scale, irrespective of the total amount of the profits of the Company. (Resolution of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 1922, replacing the Resolution of 1888.) No Fellow or Member of the College shall be engaged in trade, or dispense medicines, or make any engagement with a Pharmacist [altered from Chemist] or any other person for the supply ofmedicines, or practise Medicine or Surgery in partnership, by deed or otherwise, or be a party to the transfer of patients or of the goodwill of a practice to or from himself for any pecuniary consideration. (Bye-law 178 of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 1922, alterations in italics.)l This paper examines the implications of an historical drama at the Censors' Board of the Royal College of Physicians of London (henceforth RCP) in the late 1880s and 1890s. -

From Here to Immortality: Anti-Aging Medicine

FromFrom HereHere toto Immortality:Immortaalitty: AAnti-AgingAnnntti-AAgging MMedicineedicine Anti-aging medicine is a $5 billion industry. Despite its critics, researchers are discovering that inter ventions designed to turn back time may prove to be more science than fiction. By Trudie Mitschang 14 BioSupply Trends Quarterly • October 2013 he symptoms are disturbing. Weight gain, muscle Shifting Attitudes Fuel a Booming Industry aches, fatigue and joint stiffness. Some experience The notion that aging requires treatment is based on a belief Thear ing loss and diminished eyesight. In time, both that becoming old is both undesirable and unattractive. In the memory and libido will lapse, while sagging skin and inconti - last several decades, aging has become synonymous with nence may also become problematic. It is a malady that begins dete rioration, while youth is increasingly revered and in one’s late 40 s, and currently 100 percent of baby boomers admired. Anti-aging medicine is a relatively new but thriving suffer from it. No one is immune and left untreated ; it always field driven by a baby- boomer generation fighting to preserve leads to death. A frightening new disease, virus or plague? No , its “forever young” façade. According to the market research it’s simply a fact of life , and it’s called aging. firm Global Industry Analysts, the boomer-fueled consumer The mythical fountain of youth has long been the subject of base will push the U.S. market for anti-aging products from folklore, and although it is both natural and inevitable, human about $80 billion now to more than $114 billion by 2015.