Interview 21/11/03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judges' Annual Report

Supreme Court of Victoria 2002–04 Annual Report SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA 2002–04 JUDGES’ ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS LETTER TO THE GOVERNOR Court Profile 1 To His Excellency Year at a Glance 2 The Honourable John Landy, AC, MBE Report of the Chief Justice 3 Governor of the State of Victoria and its Chief Executive Officer’s Review 7 Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia Court of Appeal 10 Dear Governor Trial Division: Civil 13 We, the Judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria have the honour to present our Annual Report Trial Division: Commercial and Equity 18 pursuant to the provisions of the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial years of Trial Division: Common Law 22 1 July 2002 to 30 June 2003 and 1 July 2003 to 30 June 2004, including a transitional 18-month Trial Division: Criminal 24 Judges’ Report, reflecting the change in reporting period from calendar year to financial year. Masters 26 Funds in Court 29 Court Governance 31 Yours sincerely Judicial Organisational Chart 33 Judicial Administration 34 Court Management 36 Service Delivery 37 The Victorian Jury System 40 Marilyn L Warren The Court’s People 42 Chief Justice of Victoria Community Access 43 10 May 2005 Finance Report 2002–03 and 2003–04 45 Senior Master’s Special Purpose Financial Report for the John Winneke, P P D Cummins, J D J Habersberger, J Year Ended 30 June 2003 50 W F Ormiston, J A T H Smith, J R S Osborn, J Senior Master’s Special Purpose Stephen Charles, J A David Ashley, J J A Dodds-Streeton, J Financial Report for the F H Callaway, J A John -

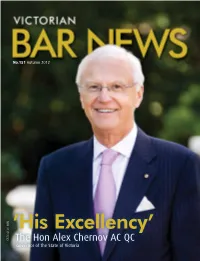

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Retirement of Commander the Honourable John Winneke AC RFD RANR

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 133 ISSN 0159-3285 WINTER 2005 Retirement of Commander The Honourable John Winneke AC RFD RANR Legal Profession Act 2004 Disclosure Requirements and Cost Agreements Under the Legal Profession Act 2004 Farewell Anna Whitney Obituaries: James Anthony Logan, Carl Price and Brian Thomson QC Junior Silk’s Bar Dinner Speech Reply on Behalf of the Honoured Guests to the Speech of Mr Junior Silk The Thin End of the Wedge Opening of the Refurbished Owen Dixon Chambers East The Revolution of 1952 — Or the Origins of ODC Of Stuff and Silk Peter Rosenberg Congratulates the Prince on His Marriage The Ways of a Jury Bar Legal Assistance Committee A Much Speaking Judge is like an Ill-tuned Cymbal March 1985 Readers’ Group 20th Anniversary Dinner Aboriginal Law Students Mentoring Committee Court Network’s 25th Anniversary Au Revoir, Hartog Modern Future for Victoria’s Historic Legal Precinct Preparation for Mediation: Playing the Devil’s Advocate Is It ’Cos I Is Black (Or Is It ’Cos I Is Well Fit For It)? What you do with the time you’ll save is your business Find it fast with our new online legal information service With its speed and up-to-date information, no wonder so With a range of packages to choose from, you can many legal professionals are subscribing to LexisNexis AU, customise the service precisely to the needs of your practice. our new online legal information service. You can choose And you’ll love our approach to online searching – we’ve from over 100 works, spanning 16 areas of the law – plus made it incredibly easy to use, with advanced emailing and reference and research works including CaseBase, Australian printing capabilities. -

A BRIEF HISTORY 1892 Metropolitan Junior Football Association Began at Salvation Army Headquarters, 62 Bourke Street, Melbourne

A BRIEF HISTORY 1892 Metropolitan Junior Football Association began at Salvation Army Headquarters, 62 Bourke Street, Melbourne. W.H. Davis, first President and E.R. Gower, first Secretary. Alberton, Brighton, Collegians, Footscray District, St. Jude’s, St. Mary’s, Toorak-Grosvenor and Y.M.C.A. made up the Association. 1893 Olinda F.C., University 2nd and South St. Kilda admitted. 1894 Nunawading F.C., Scotch Collegians, Windsor and Caulfield admitted. Olinda F.C., University 2nd, Footscray District and St. Jude’s withdrew. 1895 Waltham F.C. admitted. Toorak-Grosvenor Y.M.C.A. disbanded. 1896 Old Melburnians and Malvern admitted. Alberton and Scotch Collegians withdrew. L.A. Adamson elected second President. 1897 V.F.L. formed. M.J.F.A. received 2 pounds 12 shillings and 6 pence as share of gate receipts from match games against Fitzroy. Result Fitzroy 5.16 defeated M.J.F.A. 3.11. South Yarra and Booroondara admitted, Old Melburnians withdrew. Waltham disbanded 15/6/97. Booroondara withdrew at end of season. 1898 Leopold and Beverley admitted. St. Mary’s banned from competition 7/6/1898. 1899 Top two sides played off for Premiership. J.V. (Val) Deane appointed Secretary. Parkville and St. Francis Xaviers admitted, St. Francis Xaviers disbanded in May 1899 and Kew F.C. chose to play its remaining matches. 1900 South Melbourne Juniors admitted. 1904 Fitzroy District Club admitted. 1905 Melbourne University F.C. admitted due to amalgamation of Booroondara and Hawthorn. 1906 Fitzroy District changed name to Collingwood Districts and played at Victoria Park. Melbourne District Football Association approached to affiliate with M.J.F.A. -

The Grounds & Facts

THE GROUNDS & FACTS GROUNDS & FACT From:- 1 to 82 1. Queen Elizabeth the Second Sovereign Head of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem Apparently Queen Elizabeth the Second is the sovereign head of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem and as such the Constitution of the State of Victoria is fraudulent in that a United Kingdom Monarch purportedly a Protestant Monarch is the sovereign head of an International Masonic Order whose allegiance is to the Bishop of Rome. 2. Statute by Henry VIII 1540 Banning the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem Specific Points in the Statute of 1540 A. Knights of the Rhodes B. Knights of St John C. Friars of the Religion of St John of Jerusalem in England and Ireland D. Contrary to the duty of their Allegiance E. Sustained and maintained the usurped power and authority of the Bishop of Rome F. Adhered themselves to the said Bishop being common enemy to the King Our Sovereign Lord and to His realm G. The same Bishop to be Supreme and Chief Head of Christ’s Church H. Intending to subvert and overthrow the good and Godly laws and statutes of His realm I. With the whole assent and consent of the Realm, for the abolishing, expulsing and utter extinction of the said usurped power and authority 1 3. The 1688 Bill of Rights (UK) A. This particular statute came into existence after the trial of the 7 Bishops in the House of Lords, the jury comprised specific members of the House of Lords -The King v The Seven Bishops B. -

Commbar Celebrates Its First Decade

VICTORIAN No. 131 ISSN 0159-3285BAR NEWS SUMMER 2004 CommBar Celebrates Its First Decade Welcomes: Judge Sandra Davis and Judge Morgan-Payler Farewells: Judge Warren Fagan and Judge William Michael Raymond Kelly If Hedda Met Hamlet — Would They Still be Bored? The Twilight of Liberal Democracy Indian Rope Trick BCL: The Open Door to the Bar Chief Justices Warren and Black Address Senior Counsel The Heirs of Howe and Hummel Launch of the Trust for Young Australians Photographic Exhibition Mother’s Passion The Bar’s Children’s Christmas Party Here There Be Dragons ... Victorian Bar Superannuation Fund: Chairman’s Report The Readers’ Course Wigs on Wheels Around the Bay Verbatim Wine Report Sport/Bar Hockey 2004 Advanced and High Performance Driving �������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������� ������� �������������� ������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������ ������� ������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

8 October 2003 (Extract from Book 3)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 8 October 2003 (extract from Book 3) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services -

Going to Court

GOING TO COURT A DISCUSSION PAPER ON CIVIL JUSTICE IN VICTORIA PETER A SALLMANN, CROWN COUNSEL AND RICHARD T WRIGHT, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, CIVIL JUSTICE REVIEW PROJECT APRIL, 2000 How to make comments and submissions We would encourage comments and submissions on the discussion paper. They can be sent to the Department of Justice at the address below: Civil Justice Review Project GPO Box 4356QQ Melbourne, Victoria, 3001 Comments and submissions can also be sent by e-mail to: [email protected] The discussion can be read and downloaded from the Department of Justice homepage www.justice.vic.gov.au Adobe Acrobat® Reader will be required. Peter Sallmann LLB (Melbourne), M.S.A.J. (The American University), M.Phil (Cambridge) is Victorian Crown Counsel, formerly Director of the Civil Justice Review Project, Executive Director of the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration and a Commissioner of the Law Reform Commission of Victoria. Peter is admitted to practise as a Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Victoria. He has held a number of academic posts in law and criminology, and served on a variety of Boards and Inquiries, including the Premier’s Drug Advisory Council (the Penington Inquiry) and has published widely on judicial administration and related topics. Richard Wright B.Ec (Hons) (La Trobe) LLB (Melbourne) is Associate Director of the Civil Justice Review Project, formerly Chairman of the Residential Tenancies Tribunals and Senior Referee of the Small Claims Tribunal, Executive Director of the Law Reform Commission of Victoria, Management Consultant in the public and private sectors and has held policy advisory positions in the Australian Tariff Board, Prices Justification Tribunal and the federal Departments of Industrial Relations and Prime Minister and Cabinet. -

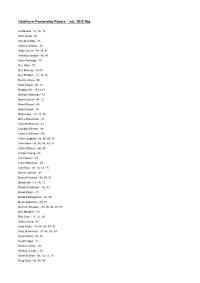

Hawthorn Premiership Players - Incl

Hawthorn Premiership Players - incl. 2015 flag Al Martello - 71, 76, 78 Allan Goad - 76 Alle de Wolde - 78 Andrew Gowers - 91 Andy Collins - 88, 89, 91 Anthony Condon - 89, 91 Barry Rowlings - 76 Ben Allan - 91 Ben McEvoy - 14,15 Ben Stratton - 13, 14, 15 Bernie Jones - 76 Brad Sewell - 08, 13 Bradley Hill - 13,14,15 Brendan Edwards - 61 Brent Guerra - 08, 13 Brent Renouf - 08 Brian Douge - 76 Brian Lake - 13, 14, 15 Bruce Stevenson - 71 Cam McPherson - 61 Campbell Brown - 08 Chance Bateman - 08 Chris Langford - 86, 88, 89, 91 Chris Mew - 83, 86, 88, 89, 91 Chris Wittman - 88, 89 Clinton Young - 08 Col Youren* - 61 Colin Robertson - 83 Cyril Rioli - 08, 13, 14, 15 Darren Jarman - 91 Darrin Pritchard - 88, 89, 91 David Hale -13, 14, 15 David O’Halloran* - 76, 83 David Parkin - 71 David Polkinghorne - 76, 78 Dean Anderson - 89, 91 Dermott Brereton - 83, 86, 88, 89, 91 Des Meagher - 71 Don Scott - 71, 76, 78 Garry Young - 61 Gary Ayres - 83, 86, 88, 89, 91 Gary Buckenara - 83, 86, 88, 89 Geoff Ablett - 76, 78 Geoff Angus - 71 Graham Arthur - 61 Graham Cooper - 61 Grant Birchall - 08, 13, 14, 15 Greg Dear - 86, 88, 89 Greg Madigan - 89 Ian Bremner - 71, 76 Ian Law - 61 Ian Mort* - 61 Ian Paton - 78, 83 Isaac Smith - 13, 14, 15 Jack Cunningham - 61 Jack Gunston - 13, 14, 15 James Frawley - 15 James Morrissey - 88, 89, 91 Jarryd Roughead - 08,13,14,15 Jason Dunstall - 86, 88, 89, 91 John Fisher* - 61 John Hendrie - 76, 78 John Kennedy Jnr - 83, 86, 88, 89 John McArthur - 61 John Peck* - 61 John Platten - 86, 88, 89, 91 John Winneke - 61 Jonathan Simpkin - 13 Jordan Lewis - 08, 13, 14, 15 Josh Gibson - 13. -

Australia's Favourite Beer

r OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE VICTORIAN AMATEUR FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION REGISTERED FOR FOSTING AS A FUBLICATIO N CATEGORY"B" Australia's favourite beer. Another Carlton Product The future is assured. AB3590/85 VAUGHAN PRINTING PTY . LTD . 624 High Street, East Kew. Telephone : 817 4483 . A Member of the National Mutual Group of Companies ~s ~~t~ "rT,) m, 1-91?, vie® w by Ross Booth Foster's Lager- Marcellin's 17 point win over Old Scotch gives the Eagles a chance of remaining in A Section at the expense of either Old Scotch or University Blues . A symbol of Australia percentage . All three clubs are on 24 Points separated only by Scotch started well but Marcellin gradually got the better of the Cardinals with 5 goals in the second term and 6 goals in the third quarter. Eagle full forward for almost a century. display . Mick Day contributed 5 goals in a polished Caulfield Grammarians pulled the surprise of the round with their 2 goal win over De La drop to 3rd . Caulfield slipped right away in the third term and it would have been more but forSalle missed who chances . In the last quarter De La Salle came back as is reflected with their final quarter scorecard ofbut 5 it was their turn to miss goalscoring opportunities best afield! .11 . Caulfield's Mark McClelland at full back was Since the Fosters brothers brewed the Ormond moved into the four with a 28 point win over changing many times throughout Uni Blues. It was a desperate game with the lead first distinctive Australian lager in 1888 . -

The Hon. John Harber Phillips Ac Qc

2401 THE HON. JOHN HARBER PHILLIPS AC QC Criminal Law Journal Obituary September 2009. The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG CRIMINAL LAW JOURNAL OBITUARY THE HON. JOHN HARBER PHILLIPS, AC QC John H. Phillips, a regular contributor to this Journal, died in Melbourne on 7 August 2009. He was greatly admired as a criminal lawyer. His death leaves a space in these pages that it is impossible adequately to fill. He was 75 years of age at the time of his death. John Phillips was born in Melbourne on 18 October 1933. He was educated at convent schools and De La Salle College. He took his LLB degree at the University of Melbourne, graduating with honours. Whilst studying, he worked in humble pursuits to supplement his income, including as a grape picker. He was admitted as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of Victoria in 1958 and called to the Victorian Bar soon after. He quickly developed a reputation as a master of trial techniques. His legal skills and interests lay especially in criminal law and the law of evidence, so necessary in criminal trials. He was noted as a cross- examiner. In part, his skill grew out of hard work on his briefs. But it was refined by his charming, unassuming manner, which was liable to deceive his victims into thinking that he was harmless or even on their side. In and out of court, his good manners and unflappable courtesy were legendry. At the Bar, J.H. Phillips rose through the ranks. Earlier in his career as a barrister, he worked pro bono in Aboriginal communities in the Northern 1 Territory. -

Assembly Spring Weekly Book 8 2003

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 25 November 2003 (extract from Book 8) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services