Microelectronics, from Westinghouse to General Instrument to Zilog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certain Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memories, Components

In the Matter of CERTAIN ERASABLE PROGRAM- MABLE READ-ONLY MEM- ORIES, COMPONENTS THEREOF, PRODUCTS CONTAINING SUCH MEM- ORIES, AND PROCESSES FOR MAKING SUCH MEMORIES Investigation No, 337-TA-276 USITC PUBLICATION 21 96 MAY 1989 United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Anne E. Brunsdale, Chairman Ronald A. Cass, Vice Chairman Alfred E. Eckes Seeley G. Lodwick David Be Rohr ? Don E. Newquist Address all communications to Kenneth R. Mason, Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 h -.. UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20436 -. -r -_ J -. In the Matter of 1 4 1 CERTAIN ERASABLE PROGRAMMABLE 1 Investigation No. 337-TA-27g READ ONLY MEMORIES, COMPONENTS THEREOF, PRODUCTS CONTAINING SUCH 1 MEMORIES, AND PROCESSES FOR MAKING 1 SUCH MEMORIES 1 NOTICE OF ISSUANCE OF LIMITED EXCLUSION ORDER AND CEASE AND DESIST ORDERS AGENCY: U.S. International Trade Commission. ACTION: Notice, SUMMARY: Notice is hereby given that the Commission has issued a limited exclusion order in the above-captioned investigation prohibiting the unlicensed importation of certain erasable programable read only memories (EPROMs) manufactured abroad by Hyundai Electronics Industries Co., Ltd. as a contractor for General Instrument Corporation and/or Microchip Technology, Inc., whether in the form of single-unit packages, incorporated into a carrier of any form, mounted on a circuit board of any configuration, or contained in certain products, except for EPROMs which are the subject of a consent order issued by the Commission on August 25, 1988. In addition, the order prohibits the unlicensed importation of certain EPROMs manufactured abroad for Atmel Corporation, whether in the form of single-unit packages, incorporated into a carrier of any form, mounted on a circuit board of any configuration. -

LINE CARD Product Categories Manufacturing

860 N. Richmond Avenue • Lindenhurst, NY 11757 PH: 631-861-4100 • Fax: 631-861-4101 Website: prideelectronics.com • E-mail: sales@ prideelectronics.com LINE CARD Pride Electronics is a world class distributor and subcontractor that was established more than 60 years ago. Our senior management team averages more than forty years of industry experience. While specializing in hard-to-find com- mercial and military electronic components and electromechanical products, we also have BPO agreements and multiple JIT programs. With offices on the East and West coasts of the USA as well as in Canada, we are ready to solve your procurement requirements. Our warehouses are strategically located in New York and Texas & can support same day shipping and delivery. We currently have hundreds of thousands of components in stock with access to millions more at our fingertips. Pride Electronics is ISO9001/2015 and ASA100 certified.. PRODUCT CATEGORIES Active/Passive Components D-RAM Inductors Power Supplies Adapters Diodes Integrated Circuits Programmable Logic Aircraft Parts/Spares Discrete Semiconductors Interconnects Rectifiers Amplifiers Displays/Indicators/Lamps Knobs/Dials Relays/Solenoids Antennas EPROM/PROM Lamps Resistors/Networks Backshells Electromechanical Lugs Semiconductors Batteries Electron Tubes Meters Sensors Cable Assemblies Fans Microcircuits SRAM Capacitors Fasteners Microprocessors Switches Circuit Breakers Filters/Fuses Memory Terminals Coils Fuses Mosfets Transformers Connectors Hardware-Mil-Spec Motors Transistors Converters Headsets, -

10-Cv-01823-Ord United States District

10-CV-01823-ORD UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON AT SEATTLE MICROSOFT CORPORATION, CASENO.C10-1823JLR Plaintiff, FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW v. MOTOROLA, INC., et ah, Defendants. MOTOROLA MOBILITY, INC., et al., Plaintiffs, v. MICROSOFT CORPORATION, Defendant. // // ORDER-1 1 This is a breach of contract case between Microsoft Corporation ("Microsoft") and 2 Motorola, Inc., Motorola Mobility, Inc., and General Instrument Corporation 3 (collectively, "Motorola"). Microsoft claims that Motorola has an obligation to license 4 patents to Microsoft at a reasonable and non-discriminatory ("RAND") rate, and that 5 Motorola breached its RAND obligations through two offer letters. (See generally Am. 6 Compl. (Dkt. # 53).) Microsoft sued Motorola for breach of contract in this court in 7 November, 2010. (See id) 8 At this stage of the case, Microsoft and Motorola are attempting to decipher the 9 meaning of Motorola's RAND licensing obligation.1 Without a clear understanding of 10 what RAND means, it would be difficult or impossible to figure out if Motorola breached 11 its obligation to license its patents on RAND terms. The parties disagree substantially 12 about the meaning of RAND. Thus, to resolve the dispute, the court held a bench trial 13 from November 13-20,2012, with the aim of determining a RAND licensing rate and a 14 RAND royalty range for Motorola's patents. 15 These findings of fact and conclusions of law represent the culmination of the 16 court's and the parties' efforts to calculate a RAND rate and range. To establish a 17 context for these findings and conclusions, the court will briefly outline the details of 18 Motorola's RAND obligation, the patents at issue in this case, and the nature of the 19 dispute between Microsoft and Motorola. -

Playcable – a Technical Summary

PlayCable – A Technical Summary PlayCable - A Technical Summary Version: 2019-07-25 Page 1 of 46 PlayCable – A Technical Summary Contents 1 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 3 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 3 PlayCable System Architecture ....................................................................................................... 4 4 Head-End Hardware and Software ................................................................................................. 6 4.1 DataChannel Transmitter Card ............................................................................................... 6 5 PlayCable Adapter Architecture ...................................................................................................... 8 6 PlayCable Adapter Hardware ........................................................................................................ 10 6.1 Digital Subsystem .................................................................................................................. 12 6.2 PlayCable ASIC ....................................................................................................................... 14 6.2.1 Master Component Interface ....................................................................................... 14 6.2.2 Bootstrap ROM ............................................................................................................ -

Vishay AR Complete 2

VISHAY INTERTECHNOLOGY, INC. ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Fortune® Magazine (March 8, 2004) “America’s Most Admired Companies” (2004) Inclusion in “Semiconductors” Category Wall Street Journal (March 8, 2004) “Shareholder Scoreboard” Number-One Ranking In “Electric Components & Equipment” Category One of the World’s Largest Manufacturers of Discrete Semiconductors and Passive Components Vishay Intertechnology, Inc. Vishay is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of discrete semiconductors and passive electronic components. These components are used in virtually all types of electronic devices and equipment, in the industrial, computer, automotive, consumer, telecommunications, military, aerospace, and medical markets. Vishay’s global footprint includes manufacturing facilities in China and other Asian countries, Israel, Europe, and the Americas, and sales offices around the world. Its worldwide sales rank as number-one or number-two in many different product categories. Vishay’s product innovations, successful acquisition strategy, focus on cost reduction, and ability to provide “one-stop shop” service have made it a global industry leader. www.vishay.com Table of Contents Financial Highlights...................................................................1 A Message from the Chairman .................................................2 Essential Building Blocks of Electronics ...................................4 Industry Leadership, Market Strength.......................................6 The Vishay Story .......................................................................8 -

Silicon Glen 1 Silicon Glen

Silicon Glen 1 Silicon Glen Silicon Glen is a nickname for the high tech sector of Scotland. It is applied to the Central Belt triangle between Dundee, Inverclyde and Edinburgh, which includes Fife, Glasgow and Stirling; although electronics facilities outside this area may also be included in the term. The term has been in use since the 1980s. It does not technically represent a glen as it covers a much wider area than just one valley. History Silicon Glen had its origins in the electronics business with Ferranti establishing a plant in Edinburgh in 1943. NCR Corporation, Honeywell and Burroughs Corporation followed in the late 1940s with IBM being a very significant import when it opened a manufacturing facility in Greenock in 1953. Indeed this was typical of much of the early days of Silicon Glen, which were dominated by electronics manufacturing for foreign companies much more than research and development or the establishment of home grown companies. The emphasis on electronics came about due to the decline in traditional Scottish heavy industries such as shipbuilding and mining. The government development agencies saw electronics manufacturing as being a positive replacement for people made redundant through heavy industry closures and the associated training and reskilling was relatively easy to achieve. Like the bedrock of Silicon Valley was in semiconductors, Silicon Glen also had a significant influence in semiconductor design and manufacturing starting in 1960 with Hughes Aircraft (now Raytheon) establishing its first facility outside the US in Glenrothes to manufacture germanium and silicon diodes. In 1966 Elliott Automation established a production facility in Glenrothes followed by a MOS research laboratory in 1967. -

Line Card Product Categories

860 N. Richmond Avenue • Lindenhurst, NY 11757 PH: 631-861-4100• Fax: 631-861-4101 Website: prideelectronics.com • E-mail: [email protected] LINE CARD Pride Electronics is a world class distributor and subcontractor that was established more than 60 years ago. Our senior management team averages more than forty years of industry experience. While specializing in hard-to-find com- mercial and military electronic components and electromechanical products, we also have BPO agreements and multiple JIT programs. With offices on the East and West coasts of the USA as well as in Canada, we are ready to solve your procurement requirements. Our warehouses are strategically located in New York and Texas & can support same day shipping and delivery. We currently have hundreds of thousands of components in stock with access to millions more at our fingertips. Pride Electronics is ISO9001/2015 and ASA100 certified.. PRODUCT CATEGORIES Active/Passive Components D-RAM Inductors Power Supplies Adapters Diodes Integrated Circuits Programmable Logic Aircraft Parts/Spares Discrete Semiconductors Interconnects Rectifiers Amplifiers Displays/Indicators/Lamps Knobs/Dials Relays/Solenoids Antennas EPROM/PROM Lamps Resistors/Networks Backshells Electromechanical Lugs Semiconductors Batteries Electron Tubes Meters Sensors Cable Assemblies Fans Microcircuits SRAM Capacitors Fasteners Microprocessors Switches Circuit Breakers Filters/Fuses Memory Terminals Coils Fuses Mosfets Transformers Connectors Hardware-Mil-Spec Motors Transistors Converters Headsets, -

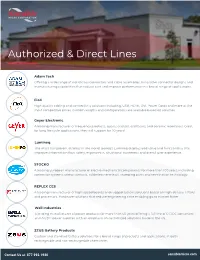

Authorized & Direct Lines

Authorized & Direct Lines Adam Tech Offering a wide range of world class connectors and cable assemblies. Innovative connector designs and manufacturing capabilities that reduce cost and improve performance in a broad range of applications. FioX High quality cabling and connectivity solutions including, USB, HDMI, DVI, Power Cords and more at the most competitive prices. Custom lengths and configurations are available based on volumes. Geyer Electronic A leading manufacturer of frequency products, quartz crystals, oscillators, and ceramic resonators. Great for long life cycle applications, they will support for 20 years! Lumineq The most transparent displays in the world. Beneq’s Lumineq displays add value and functionality that improves information flow, safety, ergonomics, situational awareness and overall user experience. STOCKO A leading European manufacturer of electro-mechanical components for more than 100 years, incluiding connector systems, crimp contacts, solderless terminals, stamping parts and termination technology. REFLEX CES A leading manufacturer of high-speed boards and rugged system solutions based on high-density FPGAs and processors. Hardware solutions that reduce engineering time enabling go to market faster. Wall Industries A leading manufacturer of power products for more than 50 years offering a full line of DC/DC converters and AC/DC power supplies with an emphasis on customized solutions made in the US. ZEUS Battery Products Custom and standard battery solutions for a broad range of products and applications, in both rechargeable and non-rechargeable chemistries. Contact Us at: 877.992.1930 sensiblemicro.com Independent Lines Actel Conexant ITT Cannon Numonyx (Micron) Silicon General Adaptec Cornell Dubilier JST Connectors NVIDIA Silicon Labs Adesto Technologies Crydom Johanson Technology NXP Silicon Image Aerovox Crystal Semiconductor Kemet-Evox Oki Semi (Lapis) Silicon Storage Tech Agere Systems Inc. -

Identification of IC Manufacturer by Logo

Identification of IC manufacturer by logo. A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Acer Acer Laboratories Actel Advanced Advanced Micro Alesis Linear Devices Devices (AMD) Semiconductor Agilent AKM Allayer Technologies Semiconductor Communications Allegro Alliance Alpha Industries Microsystems Alpha Alpha Alpha & Omega Microelectroni Semiconductor Semiconductor cs Altera American American ANADIGICs Microsystems Microsystems Analog Analog Devices Analog Systems Devices Anchor Chips Apex Apex Microtechnology Microtechnology ARK Logic Astec ATecoM Semiconductor ATI Atmel AT&T Technologies AudioCodes Aura Vision Aureal Austin Avance Logic Averlogic Semiconductor Bel Fuse Benchmarq BI Technologies Microelectronics Brooktree Burr Brown California Micro (now Devices Rockwell) Calogic Catalyst Catalyst Semiconductor Semiconductor C-Cube Centon Electronics Cherry Microsystems Semiconductor Chips and Chrontel Cirrus Logic Technologies (now Intel) ComCore Conexant Crystal (Cirrus Semiconductor Logic) Cosmo Cypress Cypress Electronics Semiconductors & Semiconductors & Microcontrollers Microcontrollers Cyrix Daewoo Dallas Corporation Electronics Semiconductor Semiconductor Dallas Dallas Data Delay Semiconductor Semiconductor Devices Davicom Diamond Diotec Semiconductor Technologies DTC Data DTC Data DVDO Technology Technology Elantec Elantec Electronic Designs (White Electronic Designs) Electronic EG&G Enhanced Memory Technology Systems Ensoniq Corp Ericsson ESS Technology Exar Exel Fairchild Microelectronics Semiconductor (now Rohm) Fuji -

The Cable History Timeline

The Cable History Timeline 1940s Late 1940s Cable brings television to small and medium sized communities without early 1950s television stations due to the Federal Communication Commission (FCC) freeze on TV licenses. 1948 Community Antenna Television (CATV) begins in small communities in rural Oregon and Pennsylvania where hilly terrain prevents broadcast television signals from reaching local businesses’ and customers' homes. Coaxial cable, amplifiers and electronic equipment are modified by CATV pioneers to meet emerging needs. 1948-50 CATV delivers off-air television programming to homes that would otherwise not receive it. Jim Y. Davidson documents his start in cable at Tuckerman, Arkansas in 1948 by signing his first CATV subscriber. CATV Magazine reports in the November 6, 1997 issue the occasion "was the initiation of telecasts from Memphis − the first station operational in the mid-South. Copyright 2014 – The Cable Center – All Rights Reserved 2 Mr. Davidson is ready with a 100-foot tower atop a two-story building, which feeds 17 outlets to his Tuckerman appliance store…plus, the single residential customer who pays $3.00 per month for the service.” Elaborate documentation exists regarding Ed Parson's start Thanksgiving Day, 1948. But, he leaves only a few years later for Alaska to fly as a bush pilot. John Walson says he built his system in June 1948 with twin lead and later replaced it with coaxial cable. Walson's system is called Service Electric. Robert Tarlton builds the first cable system to receive widespread publicity in the U.S. It may also be the first system built with the express purpose of charging a monthly fee for service.